|

Simple steps to support students as they assess the validity and intentions behind informational sources.

Once upon a time, being literate was as simple as being able to read, write, and do arithmetic. As educators, we also know literacy is a social construction, and being literate implies that an individual has the ability to interpret, produce, understand, and interrogate language appropriately. However, our understanding of what it means to be literate in the 21st century has been further complicated by the myriad of “literacies” we’ve come to recognize, including:

As the definition of literacy has broadened, so have the modes for finding and sharing information. This has increased exponentially with advances in technology, and is indicative of the natural shift in our understanding of 21st century literacy. The need to use multiple literacies to unpack information is tied to the need to interpret the many formats, sources, or media through which we obtain information. For educators, the challenge becomes more about how we need to teach students to interpret and assess information — not simply how to gain access to it.

The trouble with technology

Literacy development that includes technology can both support traditional literacies, and introduce new forms in the classroom. Technology can support each literacy type listed above by helping students gather a range of sources that will support them in discussing their ideas. Between smartphones, tablets, voice commands, and even Alexa, information is readily available everywhere. This is great, right? Yes, except that we are finding more and more examples of misinformation and disinformation in our daily diet. Recent articles in the New York Times and other educational sites such as Teaching Kids News further explore this topic, and emphasize the importance of understanding what it means to be literate within the context of this information-heavy era. Even if accessible information is every educator’s dream, we should not simply be giving fish to our students but rather, teaching them to fish — bolstering their literacy skills by helping them to make sense of the information around them by means other than traditional reading and writing. By teaching them how to assess the validity and intentions behind informational sources, we can empower them to raise concerns, and to verify unfamiliar or questionable sources.

Understanding misinformation & disinformation

According to Business Insider, the term misinformation refers to information that is false or inaccurate, and is often spread widely with others, regardless of an intent to deceive. Some of us may have done this ourselves and later realized that we misunderstood what we were sharing. Remember the game of telephone? One person would talk to the person next to them, and their words would travel from person to person around the room. At the end, we would often laugh at how distorted the original message had become from between the first person and the last. That is misinformation. Misinformation can turn into disinformation when it's shared by individuals or groups who know it's wrong, yet continue to intentionally spread it to cast doubt or stir divisiveness. Often, disinformation — or what some may call “fake news” — is generated to be deliberately deceptive. As educators become clearer about the distinction, it can be better communicated to students.

Emphasize how, not what to think

To combat misinformation and disinformation, it is essential that we teach our students to become critical thinkers. Learning critical thinking skills can also enhance academic performance by developing judgement, evaluation, and problem-solving abilities. This skill also transcends into practical aspects of daily life, and ultimately into college and career readiness. We can promote these skills by letting students know that we do not have all the answers, and instead offer them opportunities to unpack and understand information on their own.

With so much information at our fingertips each day, the importance of critical thinking skills cannot be overstated — it is imperative that we teach students how to interpret facts and assess the validity of informational sources. These skills will allow them to investigate the information they’re receiving, and identify misinformation in the process, helping them to become truly literate for the modern world.

Breathe new life into book clubs and place students at the center of their reading experience.

Time moves forward, as it always does. We can take this time to reflect on lessons learned when we unexpectedly and quickly shifted from teaching in the classroom, to teaching remotely, and then into a next normal of blended in-person and virtual learning spaces. One big takeaway from this time of critical reflection is that we aren’t starting with a blank page. Whatever the season, we can adapt tools we already have to meet the challenges we’re facing.

Breathing new life into book clubs

New tools can breathe new life into our planning and our teaching, and creating a new tool doesn’t need to be done from scratch. By connecting Ten Tips for Successful Book Clubs with our Global Mindset Framework, we can quickly create a new resource that integrates teaching 21st century skills into each reading opportunity we plan for our students. Book clubs offer many benefits to student readers, including:

A successful book club for your students will:

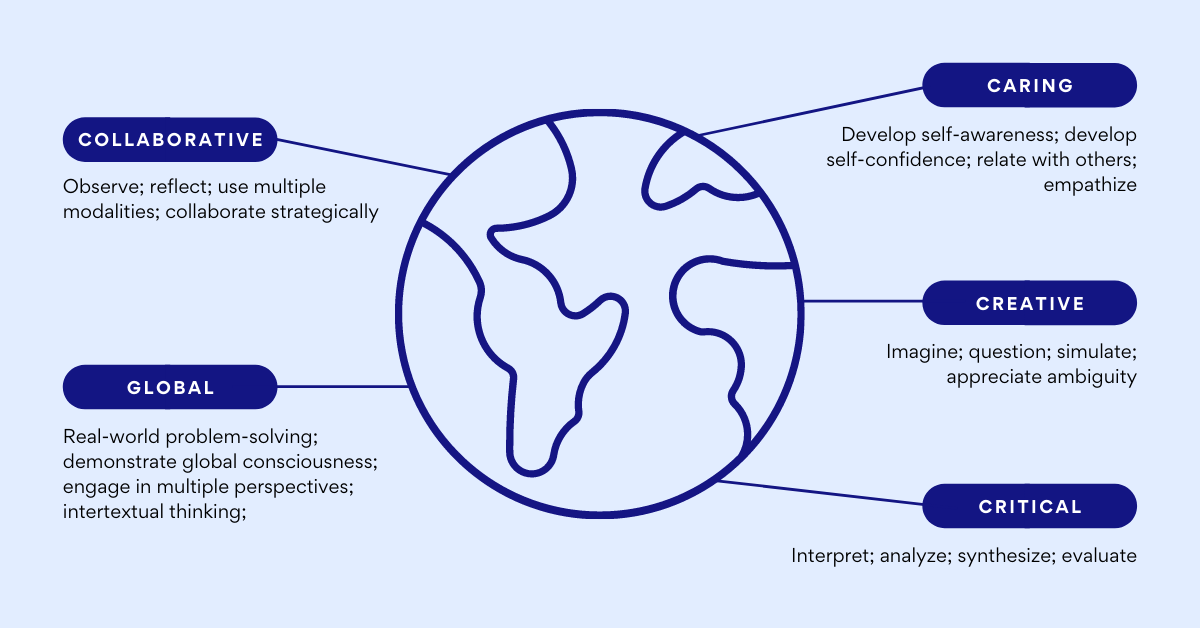

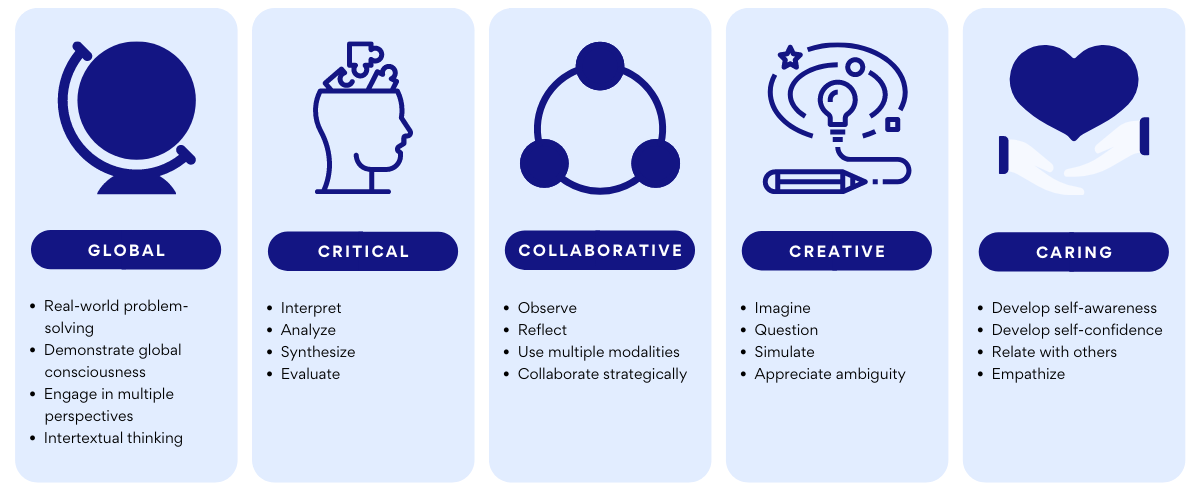

Understanding the Global Mindset Framework

Now that we’ve framed some of the characteristics of book clubs, we can connect each facet to our Global Mindset Framework. This will help us streamline our work when planning for our next book club iteration, or beginning a book club community with our students.

The Global Mindset Framework is the articulation of 21st century skills students need to navigate their present and their future, sorted into five categories of capacities: caring, collaborative, creative, critical, and global. The framework addresses key questions that teachers and school leaders struggle with as they attempt to make key concepts relevant to children in a changing world. To understand the Global Mindset Framework, we can look to the Global Learning Alliance (GLA). The GLA is the outgrowth of our groundbreaking research on the features and practices surrounding 21st century teaching and learning. It has evolved from the seeds of a research project and is now a consortium of schools and universities around the world dedicated to understanding, defining, applying, and sharing the principles and practices of a world-class education within a wide range of educational contexts.

21st century capacities

Global capacity: The capacity for students to step outside the confines of their own familiar social world to understand distant realities in order to engage productively with the world. Critical capacity: The capacity for students to develop their full critical cognitive capacities in order to be discerning and informed citizens of the world. Collaborative capacity: The capacity for students to develop habits of observation, reflection, and collaboration, and to be able to communicate in multiple modalities such as through images, words, sounds, gestures, or an integration of these modes in order to actively contribute to various discourses in the world. Creative capacity: The capacity for students to follow their curiosity by questioning or imagining in order to contribute positive improvements or inventions to their world. Caring capacity: The capacity for students to explore compassion, empathy, and self-awareness in order to develop caring partnerships with themselves, their communities, countries, and world.

Activating 21st century skills

Using the template below, we can imagine how we might combine various capacities from the Global Mindset Framework with our tips for success to generate a profile of a book club that integrates 21st century skills into student learning. We want to keep moving our teaching forward to meet the needs of today’s students, but we don’t often feel we have the time we need to recreate our plans. By layering the Global Mindset Framework over our book club planning, we can revise what we’ve already got going for us instead of starting from a blank page.

Connecting skills to next steps

Using the template above, we can customize our profile to fit a specific book — in this case, we'll use Malala Yousafzai's I Am Malala: How One Girl Stood Up for Education and Changed the World. In this model, we start with our to-do list; we imagine some of our options, and what we need to collect to complete our plan.

The task before us all is to educate students today for the world they’re poised to lead tomorrow, and as we recognize that we can no longer sustain a 20th century in a 21st century world, we must remain flexible in order to meet the dynamic needs of our students. As we look for ways to build upon the expertise and techniques already alive in our classrooms, we can easily create opportunities for students to build 21st century skills, shifting from teacher-centered instruction to an environment that puts students at the center of their reading and writing experiences.

Offer your students an opportunity to authentically engage with content, even when learning remotely.

Over the past year, school has been a rollercoaster event filled with openings, closings, virtual connections, and dramatic shifts in teaching and learning techniques and experiences. No matter the grade level or subject area, our learning spaces have been completely redefined. And it isn’t just due to in-person or online learning schedules — many teachers are finding that what worked in person may not be working as well online or in other virtual settings. Additionally, changes to state tests and other accountability measures have created opportunities for teachers to redesign their teaching methods and learning outcomes to authentically engage students in the core elements of their content areas.

Finding ways to engage students in content can be difficult, particularly when so much teaching and learning is happening remotely. We understand this challenge. Our Literacy Unbound team faced the same concerns about how to engage teachers and students in our 2020 Summer Institute — traditionally a 2-week, in-person immersive learning experience. Rooted in the belief that students learn best through authentic inquiry, curiosity, and through the multimodal embodiment of a text, Literacy Unbound brings teachers and students together with teaching artists to explore the in-depth themes of a shared text, independently. In a typical summer, we would develop a series of Invitations to Create as a way to invite and entice students into the world of the text. These invitations might prompt readers to journal, draw, collage, create a playlist, or explore some other form of expression related to a key quote or “hotspot” in the text. As readers collect their responses, they traditionally come together for a dynamic experience in which they construct an original performance based on their responses to the invitations. While much of the in-person institute needed a complete redesign to fit a virtual institute, the structure of Invitations to Create did not. Invitations provide the perfect setup for virtual reading, writing, and collaboration. And they come with plenty of choice, freedom, and personal exploration, which means that participants can be authentically engaged from the very beginning.

Creating your invitation

Even though Invitations to Create begin as prompts to pieces of literature, they’re extremely flexible and are a promising practice for all content areas and grade levels during remote and/or blended learning experiences. How can we begin to incorporate invitations into curriculum for math, science, and social studies, and beyond? To get a sneak peek of the process, we’ve developed the sample below to experiment with Invitations in Mathematics, adapted from A Guide to Crafting Invitations to Create by Dr. Nathan Allan Blom. Note: As you read, look for the examples in blue of building an invitation for A Mathematician’s Lament.

Step 1: Jot

Whatever the content, there are literacy expectations in your field. What are the reading and writing requirements in your field? In your course(s)? In the exam? Jot down some of your thinking as a warm-up. Step 2: Identify What is a text you go back to over and over again that you want to introduce to your students — or -- what is a text you already plan to use in a future lesson? Have the text handy.

A Mathematician’s Lament by Paul Lockhart

Step 3: Choose Choose a “hotspot” within the text. This is a passage of the text that captures your attention. Typically, it’s helpful if a hotspot contains:

Explain in a few words the context of the hotspot within the larger text.

In the first chapter, the author shares about a nightmare an artist has about how art is taught so that children don’t hold a paintbrush until they are young adults. Instead, they learn about art for years before they experience it for themselves. He says that life is very much like that in the real world of mathematics:

“Everyone knows that something is wrong. The politicians say, “We need higher standards.” The schools say, “We need more money and equipment.” Educators say one thing, and teachers say another. They are all wrong. The only people who understand what is going on are the ones most often blamed and least often heard: the students. They say, 'Math class is stupid and boring,' and they are right.” Step 4: Offer Offer an idea you had or a connection you made during your reading. Share with the voice of a fellow student, rather than an authority on the subject.

This makes me wonder how much more often math is seen as boring instead of beautiful.

Step 5: Connect Connect the hotspot to a piece of media to illustrate and/or extend your connections, questions, or ideas. Explore media to find something that connects and inspires you, like:

Video: The Beauty of Mathematics

Step 6: Prompt Create your prompt, using this structure: In whatever way seems best to you (equation, movement, experiment, poetry, prose, music, art, video, etc.), explore ______. Let's look at our invitation for A Mathematician’s Lament created from steps 1 - 6:

A Mathematician’s Lament by Paul Lockhart

In the first chapter, the author shares about a nightmare an artist has about how art is taught so that children don’t hold a paintbrush until they are young adults. Instead, they learn about art for years before they experience it for themselves. He says that life is very much like that in the real world of mathematics: “Everyone knows that something is wrong. The politicians say, “We need higher standards.” The schools say, “We need more money and equipment.” Educators say one thing, and teachers say another. They are all wrong. The only people who understand what is going on are the ones most often blamed and least often heard: the students. They say, 'Math class is stupid and boring,' and they are right.” This makes me wonder how much more often math is seen as boring instead of beautiful. Listen and watch this: The Beauty of Mathematics In whatever way seems best to you (equation, collage, drawing, music, etc.), explore the idea that, in the real world, math is beautiful. Include directions about how students will share their creation with you and each other. This process supports students to make their own meaning of the text, and is also a way for you and your students to experience an invitation together, whether you’re in the same concrete or virtual space. If possible, create your own response to the invitation and share it at the same time your students share theirs.

Each invitation offers an opportunity to reflect, analyze, and synthesize the text at hand. Once the invitations have been developed, students are invested in their interpretations and eager to share their ideas. This sharing is a powerful tool, inspiring motivation and encouragement across the community.

What can you invite students to create using this simple and effective structure?

Promising & practical strategies to help track the growth of children's literacy skills.

When you’re caring for children who are participating in remote learning, it can be challenging to identify and understand their progress and growth as readers. You’re likely wondering: Am I doing this right? Are we making progress? How will I know? When children are in the classroom and engaged in in-person learning, the responsibility for these questions largely lies with their teachers. However, the new normal for teaching and learning requires equal — if not more — participation from parents, in order to support and ensure the advancement of students’ reading skills.

Given how busy we are trying to balance our own work responsibilities along with the needs of our children, it can often feel easiest to default to tools like reading comprehension quizzes, multiple choice tests, or even worksheets to help recognize and assess reading progress at home. While these measures can be helpful, they certainly don’t tell the whole story. We could be missing out on identifying areas of growth and celebration, as well as a robust understanding of our children’s areas of struggle. But there are promising — and practical — strategies that parents can utilize to help monitor and track the growth of their children's literacy skills. Don't feel as though you need to create your own assessments, rubrics, or projects to achieve this — that is, unless you have the time, capacity, and energy! Instead, consider some quick, informal strategies to monitor students’ growth. These strategies can tell you a lot about a child’s reading behaviors, habits, and progress.

Habits & behaviors of good readers

In her book, 7 Habits of Highly Effective Readers, Joanne Kaminski explains, “Kids who are highly effective readers and score high on their state exams seem to have similar habits.” She goes on to explain that she has seen these habits in her own children as well as children she’s taught and tutored. The seven habits she describes are:

This list can be helpful to parents as they look for evidence of their children's reading behaviors. When these behaviors are present, you can feel good that your young learners are on the right track! As we level up our understanding of a child's reading progress, we can turn to Mosaic of Thought: The Power of Comprehension Strategies, in which the authors Ellin Oliver Keene and Susan Zimmermann outline a list of habits that are more reflective of the kind of work students are doing while reading, including:

For parents, a list like this can feel daunting. You may not know how to look for these specific skills, and are likely asking yourself questions, such as: How do I know they are inferring? How can I prompt them to determine what’s important? Identifying skills that children are exhibiting during reading is often left to teachers. Knowing what to look for There are ways to simplify the identification of reading habits and skills so that you can determine what children are doing before, during, and after their reading. We can break down more complex reading habits into observable actions, behaviors, or concrete examples that signify the deeper learning that is taking place. When it comes to reading, we can look for the following: Stamina If your child is reading for long(er) periods of time, this is great! Interest and stamina are very important, especially as books increase in demands and complexity. Fluency Have your child read to you! This can be a great way to monitor fluency, decoding, and self-correction strategies on the part of students. Comprehension and thinking skills: A simple set of questions can be very telling when it comes to a child’s predicting, inferring, and comprehension skills. You can use these same questions each time they read, and students can either answer for you, or as part of writing and drawing exercise. Here are some suggestions for what you can ask a child before, during, and after they read:

Thoughts about reading Talk to your child about what they are reading. Ask them about the kinds of books they are reading, what they're enjoying (or not enjoying), and why. This can help you gain insight into your child’s general attitude toward reading, the kinds of books they gravitate toward, and the types of books that they find easiest to read.

When you've got young learners in your home, you deserve a lot of credit for balancing work, at-home learning, childcare, and household tasks. What you’ve been able to do during this unique time has been nothing short of remarkable. Remember that when it comes to supporting learning at home, we can monitor a child's reading progress with simple strategies that make the process feel useful and manageable for everyone involved. Start with a strategy that feels feasible and accessible, and build from there. Happy reading!

Writing for publication can create awareness, raise social consciousness, and provide students with essential life skills.

When a student writes for publication, there is a shift in the dynamic between the student and their work. Picture yourself asking a student whether or not they spent a significant amount of time on their writing, only to have them respond, “Why would I spend time on it? It’s just for you.” In contrast, consider a student, who previously considered himself anonymous, telling his teacher, “Mr. Nick, I’m famous now!” after the book he co-authored with his classmates was published. Two very different reactions to a writing experience. How do we understand these two contrasting responses from young writers?

Founded in 2002, the Student Press Initiative (SPI) was designed to develop, foster, and promote writing across the curriculum through student publication, and revolutionize education by advancing teacher leadership in reading and writing instruction. Students transition from “writing for their teacher” to writing for an audience of their choice. To date, SPI has published over 850 books representing the original writing of over 12,000 students. SPI’s core values — project-based instruction, real-world authorship, community of learners, and celebrating student voice — resonate throughout these books. The grounding of these values raise the bar for what, how, and why students write.

Project-based instruction

We believe in using publishing for a real-world audience as a means to design and shape curriculum and expectations, as well as promote student engagement. We employ a backwards-planning model, where a final product is used to form an infrastructure for classroom instruction and activities. Through inquiry of the specific requirements and expectations of each project, teachers and students can better articulate the behaviors, artifacts, and customs necessary for the successful completion of the project — and being that publishing a book is a shared experience, students work together to support and encourage one another in new and powerful ways. Publication projects help to shape the culture, rituals, and routines that take place in the classroom. At the start of a project, a large calendar often overtakes the walls of a classroom, and teachers and students work together to identify the genre, audience, and purpose of their project, as well as establish details and deadlines. This helps establish a strong sense of community and collaboration. This is project-based learning at its best!

Real-world authorship

Real-world authorship shapes our approach to teaching and learning. Whether the audience is a class of incoming freshmen or first-year teachers in training, we work to connect young writers with actual readers. In the SPI model, classrooms become publishing houses in which teachers and students collectively shape an editorial vision. By exploring questions, issues, or concerns that exist in the world, their community, or within a specific content area, teachers and students collaborate to define a meaningful genre, theme, and audience. Writers then work to understand the expectations of their audience as they craft pieces with real readers in mind. No matter the content, there is always a real-world model that can demonstrate student learning with panache and voice that will engage readers. Through participation in a publication project, students develop skills and processes similar to those of professional authors. Students are supported through pre-writing and a gathering of ideas, drafting while consistently revising and editing, and finally, publishing, where they format and polish their writing to prepare for publication. Students experience “real” expectations and deadlines for publishing their book. Through these experiences, a strong sense of excitement, energy and urgency emerges.

Community of learners

SPI challenges traditional notions of “experts” in the classroom. Inspired by the work of Lave and Wenger (1996) and what they call “communities of practice,” we aim to cultivate students’ sense of expertise as writers by engaging in processes such as thoughtful inquiry of mentor texts, peer review, and peer editing. Through such processes, teachers and students work to establish a community of writers, consisting of many experts and many resources for learning and growing as authors. We encourage teachers and students to engage with a variety of texts as they begin to define qualities and attributes of powerful writing. As students learn the skills needed to write successfully, they also become experts in the project’s central theme as they read mentor texts, break genres down into smaller components, and ultimately, craft pieces that represent their learning and culminate in a final publication. A project designed around an in-depth genre study and inquiry invites students into a shared experience, and allows teachers to craft a thoughtful curriculum that addresses specific content and skills.

Celebrating student voice

Every student has a unique voice. Rather than celebrate the work of select students, we aim to celebrate the work of all students, using publication and celebration as a way to leverage and encourage participation. We believe every project should culminate in celebration — whether teachers and students decide to host a large-scale public reading at a local bookstore, smaller readings at locations such as their own school auditorium or classroom, or virtually with classmates, families, and friends. Celebrations — no matter their size or format — are powerful and rewarding experiences, and allow students to proudly share their writing with their community.

Writing can serve as a tool for creating awareness, raising social consciousness, and providing students with essential life skills. Our core values change the perspective and perception of writing for students around the world. These values, deeply embedded in our publications, reflect best practices for teaching writing in the 21st century, and help prepare students to succeed in lifelong learning.

To learn how you can partner with the Student Press Initiative and bring your students' writing to life, please reach out to us here.

Although personal, expressive writing is not necessarily a measurable outcome of learning, it is possibly some of the most important writing that we can ask students to do.

“Writing to learn” is a powerful concept that has long been espoused by literacy educators. In practice, writing to learn includes low-stakes writing assignments that generate authentic responses to prompts on a variety of topics. The goal of writing to learn is simply to unpack a subject, and the primary audience is the writer him/herself.

Some of the most powerful writing to learn practices include personal, expressive writing that allows us to reflect on how we are feeling and thinking. This may take the form of quick-writes in response to a question, journal entries, or letters to ourselves and others. Although personal, expressive writing is not necessarily a measurable outcome of learning, it is possibly some of the most important writing that we can ask students to do. Personal writing not only helps students develop their voice, but offers them precious space to reflect and process their feelings and thoughts, in order to feel emotionally strong and balanced. James Britton adds that expressive writing helps students academically, to “discover, shape meaning, and reach understanding.” As we plan instruction, whether remote or in-person, creating space for expressive writing is crucial, especially during times of crisis or change. During the remote learning period that has surfaced due to the COVID-19 crisis, teachers and schools across the world have worked overtime to reach and engage their students. Yet, even in cases where students appeared to have adequate access to digital devices, attendance was often lower than usual, particularly in middle and high schools in low-income neighborhoods.

Prioritizing mental health

When Principal Dr. Charles Gallo and his team at the New York City Charter High School for Computer Engineering, and Innovation in the Bronx — where I partner as an instructional and curricular coach — questioned students and their families about their low attendance, students reported feeling isolated, unmotivated, and in some cases, depressed, despairing, or scared. Dr. Gallo realized that his students’ social-emotional health and well-being needed to be tended to first. His students weren’t learning if they were not engaged, and they couldn’t engage if they were scared, depressed, or lonely. Swiftly responding, Dr. Gallo encouraged teachers to use their professional judgement to deviate from their planned units and lessons to prioritize students’ mental health and engagement by offering students opportunities to reflect and process their emotions and experiences around the pandemic. Encouraged by their principal, AECI faculty incorporated journal writing into their classes, which eventually evolved into plans for a schoolwide interdisciplinary project, grounded in personal, reflective writing. Students would craft responses to relevant essential questions, such as: How has the COVID-19 crisis had an impact on your personal life? How has it had an impact on society? What do you propose to solve or address the crisis?

Digital opportunities

In a digital world, where distance may make it challenging to interface with each student and check in about how s/he is doing, online options — such as Google Docs and Padlet — offer valuable asynchronous opportunities to read and respond to student writing with advice or supportive words. While sharing personal writing online demands trust and confidentiality, some students have shared that the experience of writing into a Google Doc (as opposed to a notebook) makes them feel braver. For students who don't have access to devices, journaling in a notebook or on paper is a terrific low-tech option for reflection. Incorporating these practices into your lessons can be as simple and informal as asking students to respond to a prompt that connects with the day’s topic. If you want to dig in further, consider some of these ideas:

An entrypoint to abstract thinking

Dr. Gallo and his faculty first incorporated journaling into their instruction as a way to help students process and express their complex and troubling feelings. Expressing oneself through writing (whether on paper, by typing a note on a phone, or working within a Google Doc) allows us to identify and understand our thoughts, which in turn, helps us become more confident, calmer, and balanced. When we reflect on and process our thinking, we can also start to make crucial connections to comprehend more abstract concepts and ideas. This is how learning begins to happen. At AECI, students’ responses to how has the COVID-19 crisis had an impact on your personal life? became an entrypoint into an exploration of the more abstract second part of the essential question — how has the COVID-19 crisis had an impact on society? In Math and Science classes, students used their writing as a springboard for interpreting data that showed how COVID-19 affected their communities. In History classes, students connected the current pandemic to the Black Plague and the 1918 Spanish Flu, using resources such as historical journals, information from the New York Times, and the Smithsonian.

A call to action

Following their investigation of the connections between personal experience and the societal impact felt by COVID-19, AECI students began to address the final essential question: What are your recommendations for addressing or solving the COVID-19 crisis? In keeping with the stages of Karen’s Hesse’s Depth of Knowledge framework and CPET’s Rigormeter, students moved from exploring their concrete realities to analyzing data and evidence, developing their own theories, and, finally, proposing a call to action. The project at AECI will culminate in a schoolwide portfolio of student writing and artwork, as well as letters to politicians that will incorporate supporting evidence from each discipline and propose solutions to elements of the COVID-19 crisis. Although AECI is focusing specifically on COVID-19, this type of interdisciplinary project can work for any relevant topic that’s applicable to your community.

For many of us educators, the demands of content, testing, or curriculum can leave us feeling as though we don't have time to incorporate personal writing into our lessons. However, when we recognize the benefits that come from creating space for students to make sense of their thoughts and feelings, we can see how this work is essential to student engagement, and how it can support the introduction of new content. When students feel emotionally balanced, personally engaged, and connected to a topic, real learning can happen — during times of crisis and every day.

Some key teaching concepts remain true, even across the world.

Literacy is defined as “the condition or quality of being literate, especially the ability to read and write”, and in education, literacy is often perceived as something teachers “teach” their students. But how can teachers increase their own literacy? And why is it important?

Along with a team of CPET educators, we recently partnered with teacher leaders in the MinHang section of Shanghai, focusing on teacher research. With the goal of preparing teachers to write a research proposal by the week’s end, we spent five days in December exploring the key aspects of teacher research, including research questions and rationale, data collection and analysis, literature review, and drawing conclusions. During our week of preparing teachers for research, we were reminded of the various types of literacy which extend beyond traditional reading and writing to include digital, media, computer, and content literacy, to name a few. For our purposes, we focused on the “literacy” of research, and found that key concepts remained true, even in Shanghai.

Humor helps just about everything

As we explored the research process, we began by brainstorming various teacher research questions that interested our group. Since we don’t speak Mandarin, we needed a translator to communicate, and were lucky enough to have Kaya Wang alongside us, who loved to laugh and make our participants laugh! Kaya posed this research question in our brainstorm: In what ways does teacher humor impact student participation? As facilitators, we know a good question when we see one, so we highlighted this question and used it for the rest of the week as we modeled each aspect of teacher research. What a difference laughter makes in any classroom! When we asked our group of teachers to complete a model review of literature on the impact of teacher humor, their research, in and of itself, became funny. By the time they began practicing research using questions of their own, they understood the process of developing and analyzing a compelling question, and they had a bit of fun, too. As facilitators, we realized how powerful it is to sneak the concept of humor into our teaching. It made all of the participants want to participate, and allowed them to understand the concepts we were teaching within the context of humor. When others walked past our classroom and heard laughing, they took a look inside...was this the classroom for “teacher research?” Why was there so much laughter? It made us examine how crucial the model is, and how delightful classrooms can be if humor is involved.

If you don't know, you don't know

While in Shanghai, we spent one evening at a grand spa with pools, baths, reading rooms, a dining area — it was lovely. Remember, this was before Coronavirus, so we had none of the concerns we would now have about going to a spa. When it was our turn to get a massage, the masseuse was asking questions (in Mandarin) and when we gestured that we didn’t understand, she spoke louder (we shrugged) and even slower (we shrugged again). We had no translation book and no phones on us (everything was in our lockers), so there was no way to translate. In an act of desperation, she took out a worn, laminated sheet to help communicate — except the characters on it were in Mandarin, so this did not help! When we discussed our spa experience later, we laughed about the misunderstandings (did we mean to get scrubbed down with a loofah sponge?), but also discussed how often this dynamic happens in classrooms. There are so many students in our care who do not have a strong background in English, and while speaking slowly and loudly may seem like a way to bridge a language gap, it won’t be helpful if the listener does not have a solid foundation in the language. If only there had been basic images or a few key words on that laminated piece of paper, we would have been able to better understand our options and the fees associated with them. (And I’m not sure we would have chosen the painful loofah scrub.) While this is not a new concept, we revisit it often, especially when creating curriculum or trying to reach online learners. When creating content, we remind ourselves of our time at the spa, and strive to incorporate clean, useful visual cues for those we're teaching.

Great teachers make great students

At its core, research is challenging. When factoring in our language barrier with the Shanghai team, the challenges increased. But time and time again, we were reminded of the importance of allowing ourselves to be students, as well as teachers. We learned as much from the educators in Shanghai as they did from us. At one point, we ventured out to order dinner from the Pizza Hut beside our hotel. After fumbling our way through trying to order a cheese pizza from the menu, the waitress held her phone near us and we learned about a wonderful translation app that made ordering easy. We spoke in English, and the app translated our words into Mandarin. This gave us great confidence as we navigated through Shanghai on our own, and in our sessions with MinHang teachers. This interaction (at Pizza Hut, of all places!) helped remind us of the importance of providing multiple entry points when navigating new content and concepts, and allowed us to position ourselves as learners in an unfamiliar environment. We found that everyone played the role of student at various times throughout the week — whether discussing research or language, we all experienced the challenges and benefits of learning. Our ability to reverse roles with those we were meant to be teaching served as a tool for professional growth, for all of us. K-12 classrooms can benefit from this role reversal, too — intentionally offering points in our instruction for student expertise to flourish will allow for increased literacy opportunities through modeling, and will offer everyone (teachers included) the chance to practice lifelong learning skills.

Our time in Shanghai broadened our own definition of literacy and how it can involve humor, visual elements, or at least a hefty dose of translations. What began as an institute focused on teacher research morphed into a collaborative learning experience that challenged assumptions and led us to conclude that there are lessons of literacy in many of our daily interactions — whether in your classroom, a local restaurant, or grand spa in Shanghai. As teachers become more entrenched in the literacy opportunities around them, they can expand their practice and deepen their craft.

High, low, and no tech approaches to differentiating instruction through text selection and literacy support.

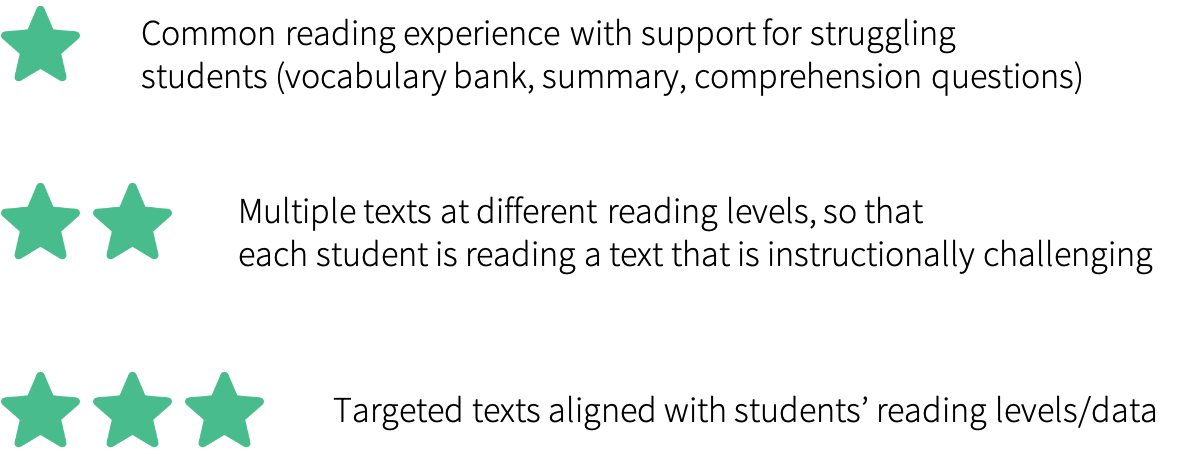

Differentiation can happen in many ways, with varying levels of complexity. Our Differentiating Like a STAR resource, designed to help educators consider entry points to differentiation, offers strategies in four categories: data, task, text, and grouping. Within each category, we outline three levels of instruction — the more stars included, the stronger the differentiation. By identifying pathways to expand differentiation, you can add depth and complexity to your lessons.

Differentiating instruction through text selection and literacy support is essential during a time of remote or blended learning. While learning remotely, students increasingly rely on learning through reading, rather than in-person lectures or teacher presentations. As students are exploring new content through texts, we can design multiple entry points to support engagement, content knowledge, and skill development. We use texts to inform our instruction at three critical levels:

When teaching in person, we often differentiate for students based on their reading levels. We may be used to differentiating a text by using a common reading support like a vocabulary word bank, or guiding questions to build comprehension. More advanced forms of text differentiation include providing multiple texts on the same topic and allowing students to make a selection. This ensures that students will have access to the main content information at the reading level that is the best fit for them. When we’re providing the highest level of differentiation for students, we’re matching specific students with an “on-level” and a “stretch level” text to support their understanding of the content and stretch their reading level.

Whether we’re teaching in-person or remotely, our biggest challenge is finding meaningful texts at different levels. You may be interested in exploring websites like Scholastic, Newsela, or Readworks — each of which offer access to texts organized by subject, topic, and grade level. A strong practice would be to identify the following:

If students are struggling with the lowest leveled text, consider adding additional scaffoldings (like the word bank or anticipatory summaries).

High-tech differentiation

We define "high-tech" as unlimited, individual access to an internet-connected device. Provide vocabulary support: Consider linking to sites like vocabulary.com, where you can create class lists, group students, and customize vocabulary lists (or select from pre-made options). You can also use this option to create quizzes and other vocabulary-building games, which will provide a complement to any reading assignment. Build student choice and autonomy by offering students a central text — for everyone to read — and then inviting students to contribute to a classroom library by finding two additional texts on the same topic. Going forward, students can select the texts they want to read based on those that have been identified for the class’ digital library. Use a formative reading assessment to identify targeted texts that can be incorporated into instructional tasks. We can use a resource like Google Forms to develop a differentiated task for students, and embed a select passage from the text into the form itself, while asking questions related to comprehension. If students answer the questions incorrectly, they can be routed to a text that’s targeted for a lower grade level. If students submit a mix of correct and incorrect responses, they can be routed to a text that matches their grade level. If students answer all questions correctly, they can be routed to a higher level text. Whether providing access to vocabulary instruction that’s parallel to the reading, or helping students discover texts at their own levels, differentiating by text level is a great way to ensure all students have a way to access the lesson.

Low-tech differentiation

We define "low-tech" as at least one hour of individual time on an internet-connected device. Add hyperlinks to potentially difficult words embedded in a shared text. This type of vocabulary support makes it easy for students to view the definition of a word, without leaving the document they’re reading. If you’re preparing an assignment in Google Docs or Word, simply highlight the word you want to define and add a hyperlink to an online dictionary. Help students utilize this support by asking them to summarize key parts of the text or define some of the vocabulary terms in their own words. This option does not require that students spend more time online, and will allow them to complete the assignment on paper rather than on the computer if that’s a better fit, given their access to technology. Offer student choice when posting an assignment to your online learning platform. Consider providing 2-3 texts as options and giving students a choice of which they’d like to read, or plan to strategically assign texts to students based on their reading levels. You can also invite students to read two out of the three texts, and offer additional points for reading multiple selections. Each interaction will help students absorb the content information, build their vocabulary, and challenge them to stretch to the next reading level. Teachers are sometimes cautious when doing this in person, as it can stigmatize students and highlight their level of academic performance. But in a remote learning setting, each task can become personalized, and this strategy can be implemented without these same concerns.

No-tech differentiation

We define "no-tech" as less than one hour on an internet-connected device. Add-on resources can accompany your lesson, and create scaffolds and supports for students as they read. For example, if a task includes a reading passage, comprehension questions, and a short response, you can create an add-on resource for vocabulary, which will provide definitions of words included in the passage. At a minimum, this word bank can help students make sense of the passage. For additional credit, we can ask students to create visual definitions of the vocabulary words, or define them in their own terms. Their work can be created using pen & paper, and then submitted by taking a simple photo. Ask students to synthesize content in their own words: Similar to the low-tech option, this begins with offering multiple texts as part of your assignment, and inviting students to choose the text that’s the best fit for them. From there, we can ask students to share what they’ve learned by writing about the topic as if they’re passing on their knowledge to students who are at a lower grade level. For example, if I’m teaching middle schools students who are learning about the three branches of government, I can extend my students’ reading task by asking them to write an explanation of this topic for third graders. The translation of the information from an on-level text to students at a lower grade level will help students think critically about what they understand.

Whether we’re teaching in-person or online, differentiating texts for students’ reading levels is complicated. We want to use everything we know about our students to match them to the right text at the right time, and provide the best scaffolds that will help them to stretch without slipping. pr

Distance learning can be challenging, especially for our young, emerging readers. What can we do to support them?

Distance learning can be challenging, especially for our young, emerging readers. In the classroom, young students are exposed to print-rich environments, and are supported and guided through a multitude of literacy activities such as phonics, guided reading, shared reading, and direct reading instruction. Now that learning is taking place in the home, there are growing concerns about the deficits young students will experience, particularly when it comes to reading. What can we do? How and when should we do it? And how can parents prioritize reading practices at home?

As a Master’s student, the focus of my thesis included understanding and improving the reading habits and attitudes of my third grade students. I launched my study by administering a survey, and provided them with a number of statements including, I like to read, I prefer reading to watching TV, and I read more than I watch TV. I had students read each statement, and then circle an emoji that best matched their feelings about the statement (ranging from positive to negative). My students’ responses, along with my observations, were pretty discouraging. I noticed many of my students didn’t want to read, or would read for a few minutes before putting their book down and saying, “I’m done.” I was determined to do something. In the next phase of my work, I reached out to parents of those students with particularly negative responses to the survey, and asked if they would be willing to participate in my study. Their participation included signing a contract in which they agreed to engage in three specific literacy practices at home: reading aloud, shared reading, and independent reading. It is these three literacy practices that I think parents should prioritize, as I believe they are simple, effective, and particularly helpful when it comes to supporting reading development outside of the classroom.

Reading aloud

Reading aloud promotes fluency and exposure. Exposure plays a significant role in reading development and cultivating a positive attitude towards reading. The parents who participated in my study agreed to read to their children for 20 minutes a day, at least three times a week. I would encourage all parents to do the same. If you can do nothing else, read aloud to your child! Expose your children to as many books as possible, and regularly engage in read alouds. This can be incorporated into a lunch break, added to a bedtime routine, or even occur first thing in the morning — whatever works best for you. If this feels too difficult, there are many read aloud resources available online that can support you, such as Epic, which offers a massive digital library for children aged 12 and under, and YouTube, which offers free access to a variety of voices and titles to choose from. If you’re ready, interested, and able to step up your read aloud game, you can engage your children further by asking simple questions: What do you notice? What does this make you think? What are you learning about ____? This kind of work promotes comprehension and inferencing skills. The tried and true think-aloud protocol — in which you share what you’re thinking and what you’re predicting — can also be a powerful model for children. I even do this with my 8-month-old. As her mother I know she’s brilliant (of course!), but can accept she is clearly too young to do deep thinking work on her own, so I point to the pictures and the words in each book, narrating what they are, for as long as she lets me. It’s never too young to cultivate a love for books!

Shared reading

Fountas and Pinnell define shared reading as a reading experience in which children and their teacher engage in multiple read alouds of an “enlarged version of a text that provides opportunities for students to expand their reading competencies. The goals of the first reading are to ensure that students enjoy the text and think about the meaning. After the first reading, students take part in multiple, subsequent readings to notice more about the text.” From there, students discuss the text, and parents or educators determine next steps for support. Ideally, parents would be able to put on their teacher hat while reading with their children, tracking and pointing to the words together, sounding words out along the way. Shared reading like this can help improve the rate at which children read, increase their fluency, and add to their enjoyment for reading. Don’t be discouraged if this feels outside of your reach. Shared reading can also mean simply engaging in shared reading time, without any additional components. Each family member can select a text of their choosing, and read near each other. Whether this happens first thing in the morning, as you read the newspaper or your favorite magazine and enjoy a cup of coffee, or before bed, as you are winding down the day and in search of some quiet time. Being exposed to others who are reading can have a positive effect on a child’s attitudes and habits around reading, as it did for my young readers.

Independent reading

The final activity in my study involved an agreement from parents to provide quiet and uninterrupted time and space to engage in independent reading for at least 20 minutes a day. One of the biggest challenges to reading at home, according to my third graders, is the lack of space and opportunity to read alone. Children are often sharing rooms, household tasks and chores need to be done, and child care responsibilities need to be managed. This, I’m sure, has only been exacerbated during the COVID-19 crisis, as everyone is now living and working from home. Home can feel even more chaotic than before, and quiet time can be a challenge. However, if you can find a calm space where children can engage in independent reading even for even small periods of time each day, it can have a positive impact on reading abilities. This space might be the corner of a room, on a bed, or even in the bathroom. We have to get creative! If you’re ready to level up your independent reading game, task your child with practicing one simple strategy while they read. This might include asking them to jot down questions as they read, notice and note (What do you notice? What does this make you think?), or it could involve a challenge to find words that start with certain letters or that contain certain blends, such as Bl or Cr. It doesn’t have to be complicated, just one strategy that will allow children to practice on their own, and then share with you.

The last tip I’ll leave you with is: if it feels like these strategies aren’t working for your readers, be prepared to throw all these strategies to the wind. Put the book down, and try again later. This is a challenging time — stress and emotions are running high — and we all know that the dynamic between parents and children, when it comes to learning, can be difficult and unpredictable. Some days our children want our help, and sometimes they don’t want anything to do with us! Give yourself some grace and flexibility. Trust that what you’re doing is enough, and remember that one day will not create lasting, negative implications for your child’s reading abilities. Be kind to yourself and to your children, and remember that tomorrow is another day.

Give students the chance to move — intellectually, physically and emotionally — into the world of a text.

We begin our session with an exercise borrowed from Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, Massachusetts. Players (our term for students and teachers who are in creative collaboration with each other) disperse throughout the room facing in any direction and are invited to move silently about the room at their own pace without collision, always passing through the center of the room en route to another side (rather than merely circling the periphery). Welcome to the act of milling and seething.

The purpose of this introductory activity is twofold: first, to foster an awareness of space. All too often in school, students are aware of neither the classroom as a physical space nor themselves and their peers as bodies coexisting within that space. Milling and seething prompts students to examine the entirety of the classroom space; at points, the facilitator leading the activity claps and says, “Look around. Are there any empty places in the room? When I clap again, move to fill them.” Students thus begin to notice the gaps and spaces within the room at any given time and to understand their responsibility to venture out and fill those gaps and spaces. And because of the mandate that they move through the center of the room as they mill and seethe, students must negotiate encounters with one another. They must become aware of where their individual bodies end and the bodies of others begin. Second, to ease players into imaginative work without any burden of “performance.” There exists no audience in this exercise; all are players. Players need only follow the directions of the facilitator (“When I clap, pause wherever you are. When I clap again, begin moving.”), and these directions shift subtly as the exercise progresses. While at first, the facilitator might ask players to “speed up (or slow down) by 50%, whatever that means to you,” directions ultimately become more like this one: “Pause. You have somewhere important to be. You’re late. When I clap again, get there.” Even with this simple direction, the players start to move into imaginative worlds.

Reimagining texts and teaching

The Literacy Unbound initiative, the driving force behind this session, was originally conceived as a grand experiment in teacher education that sought to encourage instructors to consider the power of artistic play as an opportunity to help students develop as critical, collaborative, creative readers. At its core, Literacy Unbound seeks to reinvigorate students and teachers through project-based, collaborative curricula developed around challenging texts. Throughout this process, we often witness increased student engagement and the development of a stronger classroom community. By bringing students and teachers together as creative collaborators, we’re able to reimagine the acts of reading, writing, listening, and speaking through multiple modalities. Though various aspects of this process can change, the core principles always remain the same:

Why does this work?

Through this approach, students get the chance to move — intellectually, physically and emotionally — into the world of the text. So frequently, we talk about text in the classroom. By contrast, our process allows students to talk from within the text; they speak directly from the perspective of one character and then another. They can feel the story in ways that might not otherwise be possible. At Literacy Unbound, we believe strongly that rich meaning-making happens when we find ways to experience literature together in the classroom.

Support students in establishing their voices as writers while advancing teacher leadership in reading and writing instruction.

Student writing is often read by one person (a teacher), and for one reason (a grade). But what if it could be different?

Through our Student Press Initiative, we seek to engage students in writing projects that culminate in print-based publications. These publications are designed for specific audiences, shaped around specific genres, and become widely accessible to their school community and the general public. This process not only helps students to establish their voices as writers, but helps revolutionize education by advancing teacher leadership in reading and writing instruction.

Raising the bar for student writing

Though each publication is a unique reflection of its student authors, the five phases of our publication process remain constant:

Publication in action: personal narratives from the Bronx

This spring, we supported 9th and 10th grade Special Education students at the Bronx High School for Business (BHSB) through this process. Their teacher was eager to introduce a project that would provide her students the opportunity to share a meaningful experience through the writing of a personal narrative or poem. With this in mind, our coaches worked alongside the teacher and her students to facilitate a conversation about the audience for their project. We asked questions such as:

After careful consideration and deliberation, these young authors felt strongly that they wanted to write to younger members of the Bronx Business community — primarily incoming students and siblings — in an effort to offer meaningful advice. Over the course of the project, students at BHSB were able to hone and refine their writing, particularly as it relates to communicating with their chosen audience. They were able to revise their writing to include more colloquial language and tone, which they recognized would be most effective for communicating with their young and familiar audience. As a result, they published The Barriers We Faced, The Bridges We Built. This collection highlights the obstacles many BHSB students have encountered — moving to a new country, struggling in school, and disagreeing with family and friends. Though many of these obstacles seemed insurmountable, these young authors were able to meet them head-on with persistence and resilience, building the bridges necessary to overcome their personal barriers.

Encourage students to adjust their writing style based on their intended audience.

Do you change the style, tone, and format of your writing depending on who the writing is for? Of course you do. Do you teach your students to do the same?

Whatever your answer, it’s important for student writers to truly analyze, discuss, and contemplate their audience. Thinking about the audience they are writing for can inject a different form of energy into students and subsequently, their writing. In addition, getting students to adjust their language and writing style based on the audience they’re interacting with is a transferable, life-long skill that will benefit them down the road. I recently introduced a Student Press Initiative project in an 11-12th grade class at one of our long-time partner schools, the Bronx’s Morris Academy of Collaborative Studies (MACS). This class, which is labeled as a Peer Group Connection (PGC) class, consists of 25 junior and senior students that act as peer mentors for incoming freshmen. These 25 PGC students participate in weekly outreaches with freshmen to help support their transition to the academic and social challenges of high school. Peer mentors and mentees that participate in PGC express an increase in their academic achievements, developed social/relationship skills, and are more motivated to graduate high school. Given the impact of this program, the staff and students at MACS wanted every high school in the Bronx to include a peer-mentorship program in their curriculum, and decided the book we would create would promote the PGC program to other principals in the Bronx. And thus, we had our audience.

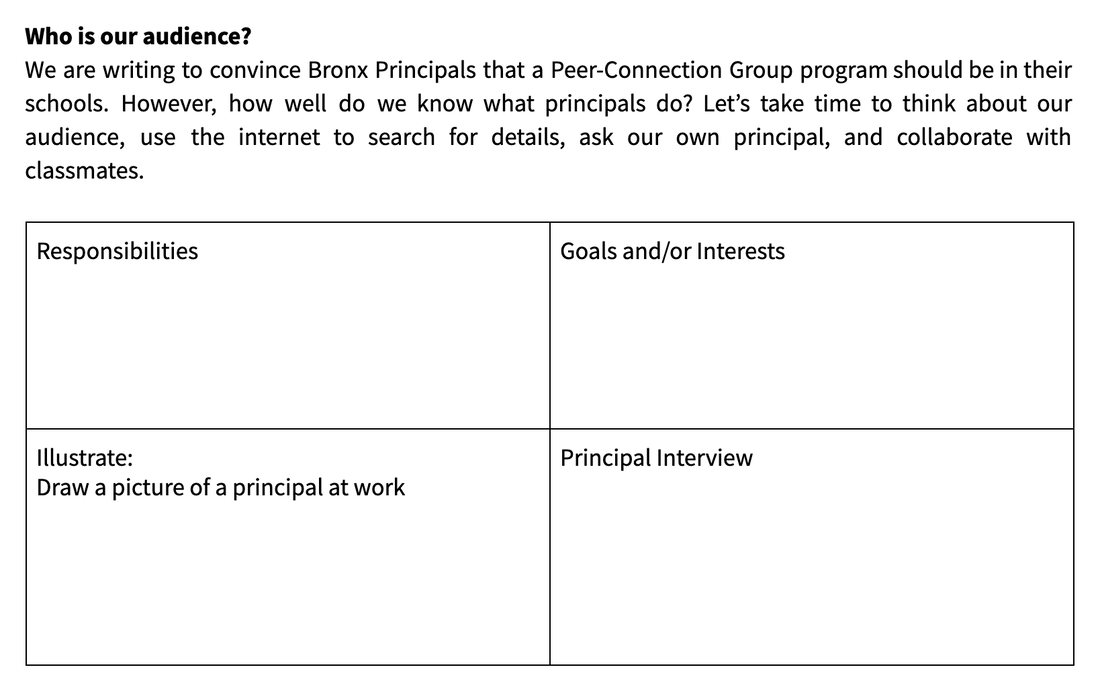

Who is our audience?

Throughout this project, the students’ writing has been powerful, raw, and passionate. At times, the energy in their writing was so strong that it was challenging to harness and refocus that energy to address our specific audience. To help students keep their audience in mind when writing, we used a few strategies. First, we (myself and the PGC teaching staff) organized the students into three writing groups: pathos, logos, and ethos. We created these writing groups to design an environment in which students could constantly engage with and think about their audience. In addition, these rhetorical devices helped influence students to produce persuasive writing from day one, which added another layer of excitement into the writing process. Second, I designed a graphic organizer called “Who is our Audience?” for students to reference. This tool allowed students to explore their audience (Bronx principals) in multiple ways — what are their interests, their responsibilities, their goals? This activity proved to be influential for students, as it tested their interview skills, allowed them to receive direct feedback from their intended audience, and become more informed writers.

Lastly, we designed a Feedback Rubric that we could use with students while revising their writing. This rubric provides a checklist that writers can reference at any point throughout the writing process, and requires evaluators to reference specific examples from the text. See below for an example of the rubric and how you might complete each section.

Feel free to adjust our graphic organizer and rubric to your own needs, or use them as a starting point for your own project! If you’re interested in seeing the product of our collaboration with the PGC group at MACS, check back on our new releases page — we’ll be releasing our publication with MACS on May 31st. I wouldn’t be surprised if the writing included in this publication convinces you to introduce a peer-mentorship program at your school!

Supporting students as they expand their vocabulary range.

A student’s command of a range of vocabulary can predict not only their academic success, but even their future job opportunities. This may seem like a bold statement, but in fact, research supports it!

As Marzano and Pickering attest, “One of the key indicators of students' success in school, on standardized tests, and indeed, in life, is their vocabulary. The reason for this is simply that the knowledge anyone has about a topic is based on the vocabulary of that information.” (Marzano & Pickering, 2005). The correlation between a student’s mastery of academic vocabulary and their success becomes even stronger as they move into high school, where they encounter a broadening variety of discipline-specific vocabulary, in which each word may actually represent a new complex concept. Consider a solution in math vs. a solution in science; a ray in math vs. a ray of sunlight in a poem; function as a noun in math vs. function as a more general verb. As students reach higher grade levels, they face increased demands to gain more specialized knowledge and to differentiate between meanings in each context. It can be a little overwhelming! To make teaching and planning for vocabulary development more manageable, I find it helpful to begin by taking action in two ways.

Supporting students to manage unfamiliar language as they read

This includes offering students tools to identify words using context clues, replacing words, identifying words by their roots or similarities to other words, or for ELLS, using cognates. Many of these tools help students read fluidly and fearlessly, taking on the challenge of unfamiliar words as hurdles to jump or work around, not roadblocks that stop them. CPET’s Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang created a simple, adaptable Monitoring for Meaning resource that students can use to figure out, track, and archive words independently as they read. Students can keep the chart right it in their notebooks and regularly build it as they encounter new words.

Identifying specific vocabulary and concepts to teach in each unit

When you plan to teach the key terms for each unit and then strategically reinforce and review the words throughout, students have a much better chance of learning and recalling key words and concepts. Sorting and categorizing, using and seeing the words in a variety of contexts, and learning through games or puzzles helps new concepts take root in the minds of your students. Consider the impact of games such as Pictionary, Taboo or Jeopardy, all of which make learning vocabulary more engaging, and in turn can make vocabulary more memorable.

How can you help students push through complex texts and find meaning in what they're reading?

When my son was five years old, his Kindergarten teacher assigned the class 20 minutes of reading for homework every night. We would sit on the couch together, and he would read to me. We didn’t get but two or three pages into the book when his mind would begin to wander, he’d start making silly jokes, or pretend to get really sleepy. I tried to be persistent. I’d prop him up on my lap, and encourage that we point at each word on the page together, sounding them out one by one. He would just sit silently.

I asked him what was wrong, and after some time in silence, he mustered the courage to whisper, “There’s a word on the page that’s bothering me.” That’s what he said -- bothering. It was as if the word was out on the playground taunting him to jump off the swing, or in the cafeteria ready to steal his lunch money. The word was bothering him. This was the first time it occured to me that reading is an emotional experience. The second time it occured to me was when I presented a workshop on reading complex texts at Teachers College. The workshop was designed for a group of middle school teachers from New York City who were embarking on a literacy initiative at their school. As part of my workshop, I wanted to explore what makes a text complex, and why. I passed out seven different excerpts from seven different fields (legal, medical, literary, mathematical, computer science, crafting, and sports) and asked the teachers to read the texts and rank them according to easiest to most difficult. While everyone was engaged in reading, I saw one teacher pick up one of the texts, promptly put it back down again, and then push the paper all the way to the edge of the table where it flew off and fell to the floor. In debriefing the experience, I asked the teacher to share with the group the strong response he had to this text. He said, “The moment I looked at it, I knew I wasn’t going to be able to understand it, and it made me feel sick to my stomach. I just wanted to get the paper as far away from me as possible.”

Reading is an emotional experience

We’ve all had this happen to us from time to time. For some, it’s when we’re reading an old English poem, or maybe it’s reading through a mathematical proof, or reading the instructions for filling out paperwork for the IRS. The big a-ha moment for us as educators is that the same reaction we might have when it comes to reading complex texts, may be the same reaction our students are having on a daily basis when we assign texts in our content areas. Here’s something else I learned from this workshop: there isn’t one type of text that’s easy, and another type of text that’s difficult. I’ve conducted this same workshop with hundreds of educators and every time, I find that different people find complexity in different texts. Our experiences with text complexity are typically based on four criteria:

It’s these four criteria that inform the emotions we feel while reading. The more criteria we’re able to match to the text, the easier it seems to us. The easier the text is to read, the better we feel about ourselves. The better we feel, the more our confidence grows and our interest in reading increases. The fewer criteria we’re able to match to the text, the more difficult it seems to us, the worse we feel about ourselves. Our confidence decreases and our interest in reading decreases.

Helping students find meaning in texts

It’s possible we’re inadvertently creating spaces where students become less interested, less confident, and less comfortable with reading because of these emotional interactions with “difficult” texts. But there are some simple solutions that we can implement if we carefully consider the four criteria for making meaning:

These four steps are not always easy, but if we’re planning with these essentials in mind, we have the power to rapidly transform resistant or reluctant readers in any content area.

If a prompt is like a camera lens, pulling your task into focus, an invitation is like a colorful string you can’t resist pulling to see what happens next.

If a prompt is like a camera lens, pulling your task into focus, an invitation is like a colorful string you can’t resist pulling to see what happens next. Writing an invitation for the reader to connect with a text can be as simple as choosing a quote and offering ways for the reader to respond, as we did with our One Book, One New York invitations when the city was reading Americanah.

When we send out invitations to our Literacy Unbound players, each day for about a month leading up to our annual Summer Institute, we wait in anticipation to find out which strings they’ll pull and what will happen next. It isn’t magic to create an invitation, though when people respond the results are often magical! Nathan Blom’s Guide to Crafting Invitations to Create provides guidance on creating “invitations [that] speak to the recipient, enticing them to run with it and see where it leads; [that] open up and spark the creative process; [that] limber up thinking and lead us into meaningful conversations.” Consider playing with all or part of the structure Nathan outlines below and see what happens for you and for your students.

A Guide to Crafting Invitations to Create

Nathan Allan Blom INSTEP Program Coordinator & Adjunct Instructor, Teachers College, Columbia University Literacy Unbound Facilitator Contextualized quote from the text Choose a “hotspot” within the text. These should be passages of the text which you find worthy of attention, for whatever reason. These hotspots might or might not be the most important passages for the novel’s plot or themes. They should be rich with:

Be sure to contextualize the quote and explain where it comes from. Give your recipient an idea of where this passage occurs within the arc of the story events, or within the theme that you want to draw their attention to. Let’s use The Color Purple as an example. The inscription to Chapter 1 states, "You better not never tell nobody but God. It'd kill your mammy." We can assume these words come from Celie's father, and that he is talking to her about the trauma he inflicts upon her. Celie takes this up and the entirety of the novel results from her letters to God (an "epistolary" is a novel in the form of letters).

Commentary on the quotation

Offer your recipient a brief commentary on the passage, without being heavy-handed. Phrase your commentary as a tentative offering of ideas, not a definitive statement of authority. Or, share the connections that occur to you when you read the passage. Or, explain the questions that arise when you read this passage, and the reasons for those questions. In Chapter 3, while trying to protect her younger sister, Nettie, from their rapist and infant-killing father, Celie says, "But I say I'll take care of you. With God help." Again, she turns to God for psychological and spiritual strength in the face of horrific events. Throughout history, people have sought spiritual refuge in the face of traumatic events, and this refuge often appears in the form of music or art. An example of this phenomenon is the tradition of African-American spirituals.

Connections to other "texts"

Putting texts into conversation with each other allows for deeper understanding. In essence, bringing in other texts is bringing more voices into the conversation. These voices add ideas and perspectives that may be absent if we only heard the single voice of the original text. The new voices complicate and contextualize meanings in unique and powerful ways. Also, sharing creative works is one of the keys to inspiring creative works. What outside media exist that illustrate and/or extend your connections, questions, or ideas? Include them in the Invitation, not as a way of defining what your recipient should do, but instead as a way of showing them what they could do and inspiring them to move further. Look to different media for inspiration:

Here are some links to African-American spirituals and gospels from performers during early 1900s (the time period of The Color Purple), and from more contemporary performers, descendants of the same tradition. There are many more examples out there. Listen and watch and respond to some of this music. Consider the interaction between the meaning of the words, and the emotional color of the music. What is being expressed? Why is it being expressed? Have you ever felt the need to express in a similar manner?

A prompt for creation

The final part of the Invitation to Create is the actual invitation itself. You must leave your recipient with a call to create. Be thoughtful in how narrowly or broadly you craft your prompting. Do you define a medium they should use (“Represent your ideas visually….”)? Do you leave it open (“Respond in whatever way you see fit….”)? Often times asking someone to move from one medium to another, such as from the written word to the visual image, for example, inspires an act of creation as the recipient tries to imagine how ideas transfer between the two. Do you guide the content of their response (“Create from the perspective of one of the silent characters of this scene….”)? In whatever way seems best to you (poetry, prose, music, art, video, dance, etc.), explore the ideas, emotions, and experiences within these moments of refuge seeking.

Invitation for The Color Purple using this structure

The inscription to Chapter 1 states, "You better not never tell nobody but God. It'd kill your mammy." We can assume these words come from Celie's father, and that he is talking to her about the trauma he inflicts upon her. Celie takes this up and the entirety of the novel results from her letters to God (an "epistolary" is a novel in the form of letters). In Chapter 3, while trying to protect her younger sister, Nettie, from their rapist and infant-killing father, says, "But I say I'll take care of you. With God help." Again, she turns to God for psychological and spiritual strength in the face horrific events. Throughout history, people have sought spiritual refuge in the face of traumatic events, and this refuge often appears in the form of music or art. An example of this phenomenon is the tradition of African-American spirituals. Here are some links to African-American spirituals and gospels from performers during early 1900s (the time period of The Color Purple), and from more contemporary performers, descendants of the same tradition. There are many more examples out there. Listen and watch and respond to some of this music. Consider the interaction between the meaning of the words, and the emotional color of the music. What is being expressed? Why is it being expressed? Have you ever felt the need to express in a similar manner? In whatever way seems best to you (poetry, prose, music, art, video, dance, etc.), explore the ideas, emotions, and experiences within these moments of refuge seeking.

Happy practicing! Enjoy the exploration, and if you’re interested in learning more, check out our Literacy Unbound initiative.

|

|