|

Creating multiple pathways for students to approach their learning will allow them to increase their personal and academic engagement.

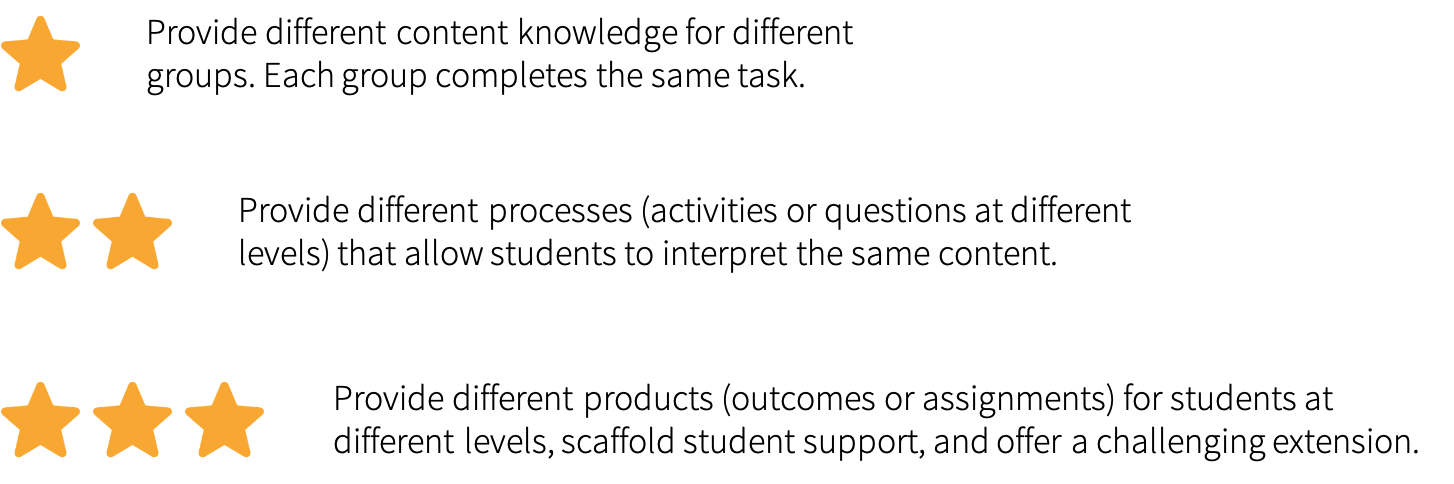

Differentiation can happen in many ways, with varying levels of complexity. Our Differentiating Like a STAR resource, designed to help educators consider entry points to differentiation, offers strategies in four categories: data, task, text, and grouping. Within each category, we outline three levels of instruction — the more stars included, the stronger the differentiation. By identifying pathways to expand differentiation, you can add depth and complexity to your lessons.

When teaching in person, we differentiate tasks by dividing content material, offering multiple processes to fit students’ learning styles, or varying the product to ensure interest and engagement. Differentiating at a distance may change our communication methods, but it doesn’t need to change our commitment to student choice. In fact, it can enhance it!

Pathways for differentiation

One classic way to differentiate instruction is to create different paths for students to demonstrate their learning. There are three ways that educators can differentiate based on the assigned task: content, process, or product. Content As you develop your curriculum, you may identify a series of content strands that students should be familiar with, and that are representative of a larger concept or theme within your instruction. When we differentiate content, we can identify some concepts and examples that are necessary for all students to know deeply, and other concepts that students should be familiar with, but may not be required to know in-depth. Differentiating this content allows educators to present a wide range of examples or scenarios as a means to teaching towards a larger concept. When differentiating content, every group takes the same steps to complete the same final product — but they begin with different content information. For example:

Product Sometimes, it is in students’ best interests to focus on the exact same content, particularly when content strands are essential to students’ understanding of a discipline, or are represented on mandated assessments. In these cases, we can keep the content the same, but invite students to represent their learning in different ways. By giving students choice in how they demonstrate their learning, we help them to tap into their natural creativity, curiosity, and intrinsic motivation. When differentiating products, it’s important to develop a scoring guide that focuses on the key content concepts that need to be represented, and to align each product outcome with those expectations. For example, you might present your students with three project options: a three-page essay, a PowerPoint presentation consisting of 10 slides, or a three-minute video. Each project can be evaluated based on the same content information and should demonstrate the same application, analysis, synthesis, evaluation, or collaboration skills. Process When preparing students for rigorous, high-stakes assessments, you may not have the freedom to pick and choose the content or the final product. In these cases, you can look at opportunities for differentiating students’ processes. Consider differentiating through process by providing various supports for students. Perhaps some students receive a glossary of key terms & definitions, while others receive a word bank, and others receive no vocabulary assistance at all (because they don’t need this additional support to make sense of the content). You can also use student notes to support process differentiation — consider inviting some students to make use of outlines, while offering two-column note taking, webs, and bullet points to others. Whether they’re working individually or in small groups, giving students a choice of how to engage in their learning process can feel highly personalized, which will enable them to walk with their best foot forward.

Making the most of online learning

When working in the world of remote teaching or blended learning, our typical teaching strategies may seem difficult to translate, which leads to defaulting to whole-class instruction that does not leverage student choice or differentiate based on student needs. But the online space offers just as many — if not more — opportunities to differentiate the task. High-Tech Many educators working in communities with on-demand access to technology are able to differentiate a task through content, process, or product using their online platform. Whether you’re using Google Classroom, Canvas, Blackboard, Moodle, or your own website, you can offer options at key points along the learning journey. In fact, it’s even easier to provide task options through distance learning, since there are no printing requirements! Within each lesson, we can create opportunities that maximize student choice. In high-tech spaces, we can post multiple assignments, graphic organizers, or focus topics and invite students to choose which they’d prefer to work with. Students can even work across class periods and be grouped with students who have shared interests, levels, or thinking processes. Students can also meet virtually through video conferencing, create small group videos, or share their process notes through pictures, video reflections, and digital artifacts. Low-Tech Some students have access to technology, but experience limitations due to time on their device, internet access, or support with using advanced features of applications. In these situations, the differentiation of content, process, or product should be made clear to students in their assignment. They may benefit from having their assignment personalized for them, and they may need flexibility if they are able to mix online and offline work. This can mean posting the task so it can be downloaded for later use (rather than just existing on a website), and creating materials that students can complete using their computer, but that don’t require internet access. No-Tech Students in the “no-tech” access category likely have less than one hour per day to access the internet, and may be logging on from a phone or tablet that isn’t connected to a printer or scanner for managing hard copy printouts. Teachers can offer entry points for these students by creating custom materials using picture models or short videos that explain what and how to complete a task with the materials they have on hand. Keep in mind that no-tech assignments can ask students to write out their responses by hand and submit assignments using photos. These assignments might also include packets of strategies or resources that can be picked up at school (and for convenience, can be picked up/dropped off during the same hours as food distribution), phone calls or text messages to students, or the option to send/receive materials by mail.

Differentiating tasks is one way we can increase student interest. Students are drawn to tasks that are personally relevant and challenging — creating multiple pathways for students to approach their learning (process), demonstrate their learning (product), or customize their learning (content), will allow them to deepen their understanding and increase their personal and academic engagement.

High, low, and no tech approaches to differentiating instruction through text selection and literacy support.

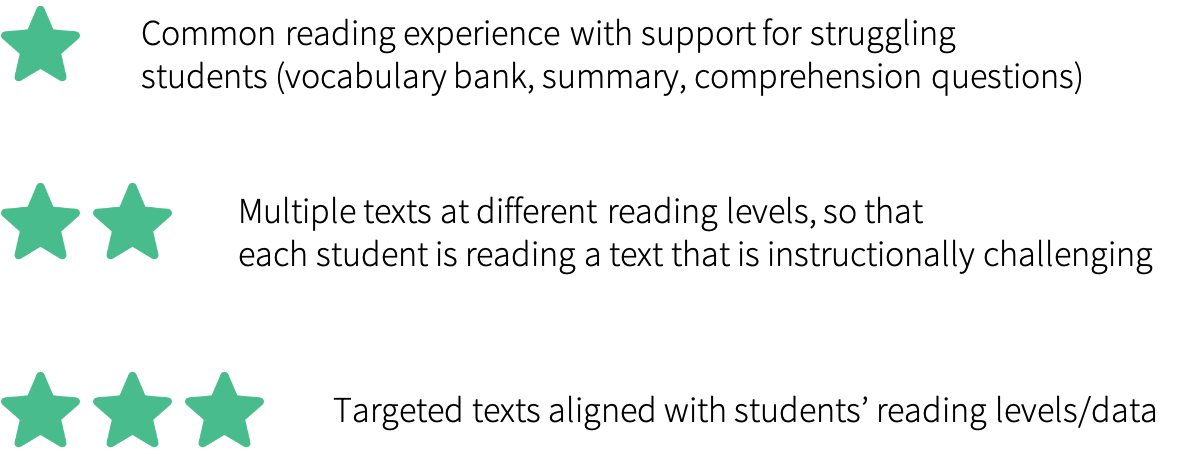

Differentiation can happen in many ways, with varying levels of complexity. Our Differentiating Like a STAR resource, designed to help educators consider entry points to differentiation, offers strategies in four categories: data, task, text, and grouping. Within each category, we outline three levels of instruction — the more stars included, the stronger the differentiation. By identifying pathways to expand differentiation, you can add depth and complexity to your lessons.

Differentiating instruction through text selection and literacy support is essential during a time of remote or blended learning. While learning remotely, students increasingly rely on learning through reading, rather than in-person lectures or teacher presentations. As students are exploring new content through texts, we can design multiple entry points to support engagement, content knowledge, and skill development. We use texts to inform our instruction at three critical levels:

When teaching in person, we often differentiate for students based on their reading levels. We may be used to differentiating a text by using a common reading support like a vocabulary word bank, or guiding questions to build comprehension. More advanced forms of text differentiation include providing multiple texts on the same topic and allowing students to make a selection. This ensures that students will have access to the main content information at the reading level that is the best fit for them. When we’re providing the highest level of differentiation for students, we’re matching specific students with an “on-level” and a “stretch level” text to support their understanding of the content and stretch their reading level.

Whether we’re teaching in-person or remotely, our biggest challenge is finding meaningful texts at different levels. You may be interested in exploring websites like Scholastic, Newsela, or Readworks — each of which offer access to texts organized by subject, topic, and grade level. A strong practice would be to identify the following:

If students are struggling with the lowest leveled text, consider adding additional scaffoldings (like the word bank or anticipatory summaries).

High-tech differentiation

We define "high-tech" as unlimited, individual access to an internet-connected device. Provide vocabulary support: Consider linking to sites like vocabulary.com, where you can create class lists, group students, and customize vocabulary lists (or select from pre-made options). You can also use this option to create quizzes and other vocabulary-building games, which will provide a complement to any reading assignment. Build student choice and autonomy by offering students a central text — for everyone to read — and then inviting students to contribute to a classroom library by finding two additional texts on the same topic. Going forward, students can select the texts they want to read based on those that have been identified for the class’ digital library. Use a formative reading assessment to identify targeted texts that can be incorporated into instructional tasks. We can use a resource like Google Forms to develop a differentiated task for students, and embed a select passage from the text into the form itself, while asking questions related to comprehension. If students answer the questions incorrectly, they can be routed to a text that’s targeted for a lower grade level. If students submit a mix of correct and incorrect responses, they can be routed to a text that matches their grade level. If students answer all questions correctly, they can be routed to a higher level text. Whether providing access to vocabulary instruction that’s parallel to the reading, or helping students discover texts at their own levels, differentiating by text level is a great way to ensure all students have a way to access the lesson.

Low-tech differentiation

We define "low-tech" as at least one hour of individual time on an internet-connected device. Add hyperlinks to potentially difficult words embedded in a shared text. This type of vocabulary support makes it easy for students to view the definition of a word, without leaving the document they’re reading. If you’re preparing an assignment in Google Docs or Word, simply highlight the word you want to define and add a hyperlink to an online dictionary. Help students utilize this support by asking them to summarize key parts of the text or define some of the vocabulary terms in their own words. This option does not require that students spend more time online, and will allow them to complete the assignment on paper rather than on the computer if that’s a better fit, given their access to technology. Offer student choice when posting an assignment to your online learning platform. Consider providing 2-3 texts as options and giving students a choice of which they’d like to read, or plan to strategically assign texts to students based on their reading levels. You can also invite students to read two out of the three texts, and offer additional points for reading multiple selections. Each interaction will help students absorb the content information, build their vocabulary, and challenge them to stretch to the next reading level. Teachers are sometimes cautious when doing this in person, as it can stigmatize students and highlight their level of academic performance. But in a remote learning setting, each task can become personalized, and this strategy can be implemented without these same concerns.

No-tech differentiation

We define "no-tech" as less than one hour on an internet-connected device. Add-on resources can accompany your lesson, and create scaffolds and supports for students as they read. For example, if a task includes a reading passage, comprehension questions, and a short response, you can create an add-on resource for vocabulary, which will provide definitions of words included in the passage. At a minimum, this word bank can help students make sense of the passage. For additional credit, we can ask students to create visual definitions of the vocabulary words, or define them in their own terms. Their work can be created using pen & paper, and then submitted by taking a simple photo. Ask students to synthesize content in their own words: Similar to the low-tech option, this begins with offering multiple texts as part of your assignment, and inviting students to choose the text that’s the best fit for them. From there, we can ask students to share what they’ve learned by writing about the topic as if they’re passing on their knowledge to students who are at a lower grade level. For example, if I’m teaching middle schools students who are learning about the three branches of government, I can extend my students’ reading task by asking them to write an explanation of this topic for third graders. The translation of the information from an on-level text to students at a lower grade level will help students think critically about what they understand.

Whether we’re teaching in-person or online, differentiating texts for students’ reading levels is complicated. We want to use everything we know about our students to match them to the right text at the right time, and provide the best scaffolds that will help them to stretch without slipping. pr

If we can begin to see some of our professional obstacles as opportunities, we can forge new pathways that will carry us forward, even when the current crisis is behind us.

Nothing is going according to plan.

Across the world, the swift transition from in-person to online education as a result of COVID-19 has created anxiety, uncertainty, grief, and a host of complex challenges for educators. Whether the transition caught us by surprise or we saw it coming, we have all faced unexpected obstacles in the wake of this crisis. But if we can begin to see some of our professional obstacles as opportunities, we can begin to forge new pathways that will carry us forward, even when the current crisis is behind us.

Designing curriculum

Obstacles Designing curriculum is hard enough, but designing a remote learning curriculum in the middle of a global pandemic is completely overwhelming. Curriculum design is often customized to the features of a time-bound, classroom-based experience, to which at-home learning bears little resemblance. Can we translate the qualities of in-person learning to diverse groups of students who will have different entry points to learning and varying levels of access? Can we provide rigorous instruction to students when exams are canceled? Can we continue with the curricular units we had planned at the beginning of the school year, even if they aren’t aligned with at-home learning? Opportunities Within each of these curriculum challenges is an opportunity that can be unlocked with one word — how. Rather than “can we...", let’s try “how can we...in high-tech, low-tech, and no-tech ways?” By asking how, we can focus not on obstacles, but action steps. This shift in our thinking can act as a catalyst to reexamining our goals, methods, and design for learning. In this moment, we have the opportunity to reimagine our curriculum for maximum engagement, intellectual curiosity, and cultural relevance. In-person learning is constrained by quantities of time: attendance, punctuality, and class periods, to name a few. Because at-home learning doesn’t exist within the same parameters, it presents an opportunity for educators to design curriculum that will engage students in learning at their own pace.

Demonstrating learning

Obstacles At the same time, at-home learning lacks the immediate presence of a classroom teacher who can answer questions at a moment’s notice, or a classmate to consult. As a result, at-home curriculum must be more explicit than its in-person counterpart. In person, a teacher may typically make oral announcements, or take loose notes on the board. To engage students in an intellectually rigorous at-home learning experience, teachers will likely need to be more detailed, more explicit, and provide more models, examples, and visuals in order for students to deepen their understanding. Opportunities As teachers articulate the nuances of content for an at-home learning experience, we have a new opportunity to develop robust materials and resources that will serve students’ needs, even when in-person learning resumes. For teachers, this type of deep reflection and planning is a unique professional learning experience that deepens our own understanding of our content and methodology. For at-home learning, teachers may want to consider structuring weeklong assignments in the form of mini-projects or inquiry investigations that will allow students to vary the time spent on them each day. Some may want to break up their learning into daily chunks, while others will be able to dive deeply into the experience for a longer period of time. The ultimate goal is not the precise number of minutes students spend on the activity, but rather how they are able to demonstrate their knowledge and skills related to the objectives. It doesn’t matter if they complete the task in 5-minute or 45-minute increments, or across 3-4 hours in one sitting — what matters is what they learn.

Connecting to students

Obstacles In-person teaching is dependent upon a teacher’s presentation skills, and their rapport with students. At-home learning requires a completely different approach, as teachers are not physically with their students. This can be very disorienting for teachers who find their energy and satisfaction from being around kids and seeing their students’ eyes light up during an a-ha! moment. Being separated from their students can leave teachers feeling isolated, disconnected, and wondering if anything they’re doing is working. Opportunities Distance learning requires us to consider all of the ways in which we can deliver content without being in the same room at the same time. Our first task is to acknowledge that our go-to model of instruction may not be possible at this time. But while distance learning is different, it doesn’t need to diminish the teaching or the learning experience. We want to start by asking questions: How do we design an opening activity to draw students into their learning? How do we deliver our mini-lesson on a new topic or concept? How do we provide students with meaningful tasks and provide feedback in a timely manner? One option includes synchronous video calls, where students log on at a specific time and engage with their class virtually. The benefits here are that teachers can present their lesson, engage students in peer-to-peer discussions, and answer questions in real time. However, this approach assumes all students have access to technology, and are able to engage at the same time without interruption. This isn’t always the case — and when students can’t engage online, it creates major concerns around equity and access. It’s for this reason that many educators see asynchronous learning as a promising practice. Using simple technology to create instructional videos, screencast presentations, or even audio recordings, teachers can present their lesson one time and distribute it 100+ times to their students in low- and no-tech ways. One of the benefits of recorded lessons (even when we aren’t teaching through a pandemic) is that students can re-watch the lesson as many times as needed in order to understand the information. This is a critical support for students who have learning disabilities, or are learning English as a second language. Being able to pause, go back, and re-watch the lesson can bolster students’ confidence, increase their comprehension, and clarify their questions. After the lesson is designed and delivered, teachers can shift their focus from delivering instruction to providing personal support, feedback, and task modifications for students at all levels. This might look like holding office hours, offering weekly check-ins with students, email correspondence, or phone calls with students or caregivers who don’t have access to technology. Using these strategies, distance learning can be expertly differentiated, highly personalized, and deeply relational.

In a time that feels topsy turvy, we have to be honest: nothing is going according to plan. This fact is scary, disappointing, and de-centering, and can produce a considerable amount of anxiety. Whether we’re novice teachers or veterans, school leaders or policymakers, we are educating in a time that requires us to find new opportunities for offering meaningful, relevant, and academically engaging learning experiences to our students. Being open to these opportunities will serve us well, even when we’ve safely returned to our classrooms.

When our lessons are thoughtfully designed and informed by student data, we can provide targeted instruction at every level of technology access.

Differentiating instruction is inherently difficult, and now that we’re doing it at a distance, it can appear even more overwhelming than before. But appearances can be deceiving. Differentiating during this period of distance learning — using some high tech, low tech, and no tech options — can be easy, efficient, and effective!

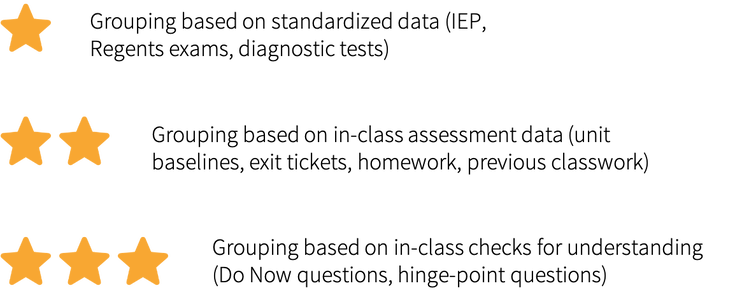

Differentiation can happen in many ways, with varying levels of complexity. Our Differentiating Like a STAR resource, designed to help educators consider entry points to differentiation, offers strategies in four categories: data, task, text, and grouping. Within each category, we outline three levels of instruction — the more stars included, the stronger the differentiation. By identifying pathways to expand differentiation, you can add depth and complexity to your lessons. When teaching at a distance, we aren’t able to rely on our typical informal observation skills to gather data about our students, including our ability to overhear conversations, see students’ confusion, or listen to their in-the-moment questions. We can, however, find alternative methods for collecting and using data to inform the next steps of our instruction. We use data to inform our instruction at three critical levels:

High-tech: Google Forms

Using the features built into Google Forms, educators can build custom assessments, surveys, pre-, during, and post-reading guides, and much more. When students answer questions within the form, you can be updated instantly. Create a clear connection to the data by turning the form into a quiz. This allows students to receive feedback about their performance, and can allow you to provide instructions for the student’s next task, based on their answers. Students who do well may be ready to move on to a more challenging activity; students who struggle may be directed to re-read or engage in continued practice. When they’re ready, students can return to the quiz to re-test their knowledge and demonstrate their learning. How can you redirect students based on their answers? Use the “go to section based on answer” feature. This feature allows teachers to create hinge-point questions within an online learning experience. Within any multiple choice question, we can establish different follow-up tasks based on a student’s response. If our answer choices are strategic (e.g. 1 correct answer, 1 close answer, 1 opposite answer, and 1 nonsense answer), students can be routed to different follow-up tasks after each question they respond to:

Using these Google Forms features is a great way for educators to create original curricular materials that blend instruction and assessment into a seamless experience for students.

Low-tech: there's an app for that!

Not everyone is up for building a differentiated task from nothing, and that’s okay — there are plenty of existing apps we can use that already have some of the basics set up for us:

These apps and others like them allow teachers to use existing platforms as a way to gather critical data about student performance.

No-tech: phone & paper

Distance learning without immediate and on-demand access to technology is extremely challenging in any circumstance, but especially amid a global health crisis. Students and families who don’t have access to technology are also those most likely to be vulnerable to housing, food, or health insecurity, and it’s in times like these that an equitable education is most at issue. While it might be less fancy, using data to inform your instruction is not less possible when working without on-demand access to technology. Here are a few no-tech solutions that can get us through these difficult times without sacrificing the importance of data-informed instruction:

Whether or not we’re with our students in person, it’s still within our reach to provide targeted instruction. When our lessons are thoughtfully designed and informed by student data, we can offer differentiated instruction at every level of technology access.

Letting go is one of the hardest parts of effective leadership — how can you set your team up for success?

We might think that the hardest part about becoming a leader is knowing the right thing to do, at the right time, and then doing it. In reality, the hardest part of becoming a leader is knowing the right thing to do at the right time, and then not doing it. Let me explain.

Leaders often find themselves in a position to manage others in an area where they’ve previously been successful. The problem is, when it comes to supervising others in doing a job we know how to do well, it’s often easier to continue to do the job ourselves than to watch others struggle through it. Face it — if we do it ourselves, it’ll get done faster, better, and everyone will see how skilled we are and they’ll learn in the process. Except...not really. In reality, it’s vice versa.

Letting go is one of the hardest parts of effective leadership

When we’re doing our jobs well, our work as leaders is to coach and supervise the tasks and responsibilities of others — and that role should take more of our time than anything else. If we’re spending the bulk of our time doing the tasks ourselves, we aren’t leading, we’re doing. The true task of a leader — as a teacher, an administrator, or even a superintendent — is to lead from the ground up, nurturing those around us to take root, grow tall, and bloom. But this process is easier said than done. In reality, even when we establish a process for delegating tasks, distributing roles, and differentiating responsibilities, it’s easy to spend all day, every day putting out fires, stopping fights, and feeling frustrated. This is because in ground-up leadership, we have to train and coach others to know how to do the right thing at the right time, even when we aren’t around. This is when leadership feels like a vice, when the weight of our leadership role feels like it has such a tight grip on us that it makes it hard to move or even breathe. When we feel the vice, we need the VERSA. VERSA is a process for leadership that includes five principles of leadership that will help us to transform our teams from the ground up, allowing us to step back while others step forward.

V is for Vision

Effective leaders set a clear vision to help their teams see what matters most. The first step for working with any team is to set a clear vision for the work they’re doing. It’s our responsibility as leaders to find the big picture vision for the task at hand, and help each person on our team to take on that vision as their own. This means they need to see value in the vision, see the role they play in reaching toward the vision, and see the vision as it fits into their own purpose in the work. To set a vision, leaders must ask themselves: What is our goal? We must remember where we want to go.

E is for Expectations

Effective leaders clearly communicate their vision and establish shared, explicit expectations — even when they seem like common sense. All conflicts are the result of missed expectations, whether known or unknown. We all have expectations of ourselves and of one another — when those expectations are not clearly defined, are not stated explicitly, or are not agreed to, we’re bound to have accidental missed expectations. We’re also bound to have purposeful missed expectations, where someone wants to leave early or doesn’t meet a deadline. Without clearly stated and agreed to expectations, it can be challenging to realistically hold people accountable for their mistakes. To establish expectations, leaders must ask: Do we agree on what needs to be done? We must remember to say what we want to see.

R is for Responsibility

Effective leaders identify who, what, when, where, and why. If it’s everyone’s job, it’s no one’s job. The idea of shared tasks and shared responsibility is great on paper, but in the real world, when the components of the task are ambiguous or the process is mysterious, we often create more problems than we solve. Responsibility entails the strategic and purposeful passing of the baton from one person to the next, for a defined period of time. We can think about it like a relay race. If everyone runs all at once, the team is doomed to fail. If no one runs a particular leg, everyone loses. Most work in teams requires thoughtful distribution of tasks, even if they can be completed by multiple people on the team. To establish responsibility, leaders must ask: Who will do what, and by when? We must remember to monitor the baton pass between team members on our project.

S is for Support (and praise)

Effective leaders provide opportunities for professional growth and strategically match people with tasks linked to their gifts and talents as often as possible. They praise with purpose. In her book Dare to Lead, Brene Brown challenges leaders to imagine that each of their team members is actually doing the best they can, without reservation. The question she leaves us with is, if that’s true (which she is very confident that it is) what does it mean about how we support them in the work? How do we determine that our team has all the skills they need to meet the demands of the task? How can we anticipate their professional learning needs, as well as create a culture where people feel comfortable coming to the front to say where they need help? If we are truly motivated by our goal, we’ll take the time and put in the effort to provide support and praise to our team members, offering feedback on what has been done well and where growth is required to meet the goal. To provide support, leaders must ask themselves: Do we have the skills to meet the expectations? We must remember that common sense isn’t always common, it’s often learned through culture and prior knowledge.

A is for Accountability

Effective leaders follow up on met and unmet expectations. In direct conversations, we can identify the obstacles to meeting expectations, collaborate on action plans for next steps, and when necessary, establish proportional consequences. Part of the challenge is that many leaders grew up in the light of the epic quote, “if you build it, they will come.” I know that I spent a lot of time believing that if I just set a clear vision, hired the right people, and created clear structures, I wouldn’t ever have to have those hard conversations, or correct someone on the team, and of course, I’d never need to fire anyone. But accountability is just as important as every other part of the process. It’s what raises the stakes, creates a fair working environment, and reinforces the values of the organization. Without accountability, anything goes...and when anything goes, everything goes. To hold our team members accountable for their contributions, we ask: What feedback or action steps will translate into met-expectations? We can remember that accountability doesn’t equal punishment, but it is a call to account — to explain what happened, why it happened, and how we can make a change in the future.

VERSA is a process for leadership that allows us to lead from the ground up — stepping back in order to move forward — and authentically move our teams towards knowing the right thing to do at the right time.

When our teams take center stage in these ways, it’s a huge win. It means as leaders, we can begin to set our sights on the future, knowing that day-to-day, our team is leading the way.

Three ways we can minimize conflicts and maximize positive learning opportunities for students.

What do you do?

I’m a teacher. Oh wow, I could never do that! [long pause] It must be so rewarding, though. I’ve had this conversation at least a hundred times, maybe more. There’s the same rhythm of awkward pauses each time, where the other person looks to say something positive, and I recall small, not-so-rewarding incidents that have happened over my teaching career. Yes, I do find my work in education, both in and out of the classroom, to be extremely rewarding when I focus on the big picture. But on a day-to-day basis, teaching can be a struggle. It’s a struggle because, contrary to popular belief, teachers do not teach Math or Science, or History — they teach students. From tiny to tall, students are actual human beings with independent identities, personal autonomy, and a will of their own. The concept of “controlling your class” is both inaccurate and impossible. On any given day, a highly effective teacher can facilitate, guide, support, foster, and nurture a positive learning environment — but we can never control it. Subsequently, creating classroom culture or managing student behaviors is a major stressor for teachers at all levels. Many teachers maintain the myth of classroom control and as a result, they may struggle to embrace student-centered instructional strategies like peer-to-peer discussions, group work, and student choice on tasks. The more fear we have, the more likely we are to become hyper-vigilant micro-managers in the classroom, which can sometimes magnify small issues and escalate conflicts, creating disruptive and potentially dangerous power dynamics that can block off relationships and erode trust between teachers and students. None of which feels rewarding, I promise. As teachers, we have a lot of power and responsibility to set the tone in our own classrooms and create a culture of learning that empowers students to engage in the lessons with respect for themselves and others. Here are three ways we can de-escalate conflicts and maximize positive learning opportunities for students.

Don't take it personally

The first thing we want to remember is that all of our students are actual human beings who typically live 23 hrs and 10 minutes a day without us. When they enter into our classroom after a bad morning, feeling hungry, distracted, or any number of other emotions, it’s easy for us to take their words and actions as a personal attack. This can put us on defense, or worse — on the offense. Before reacting, we will benefit from asking a few simple questions that will help us to strategize our next steps.

Praise publicly

Even in the smallest classes, teachers are outnumbered. As a result, we’re hyper-focused on distracting, disruptive, disrespectful, and defiant behaviors and we’re far more likely to address everything that’s going wrong, rather than what’s actually going right. Often, we’re addressing negative classroom behaviors in front of the whole class because it’s more efficient to say, “Brian, stop talking” from the front of the room than it is to walk to the back of the class and talk with Brian privately in the middle of a lesson. But culture is shaped primarily by the narrative, and as teachers, we have the privileged opportunity to set up a positive narrative in our space. By eliminating public criticism, and praising publicly instead, we have the power to create positive momentum, spotlight all the students who are doing the “right” thing, and set clear expectations for what students are supposed to do.

Reflect & redirect

Our goal is not to become afraid of addressing students’ negative behaviors directly, but rather to begin addressing them strategically. If we can remove our personal feelings from the situation, we’ll be better positioned to find a method for motivating students to fully commit to a proactive and positive learning environment. Part of that methodology is public praise — the other part is personalized reflection and redirection. Especially when working in a culture that is vastly different from one’s own, focusing on short, private conversations when it’s necessary to address a negative behavior can only have a positive impact on the culture.

Our classroom spaces will feel physically and psychologically safer when we acknowledge that students’ behavior is a form of communication, even when directed towards us. When we allow ourselves to be personally offended, we are likely to simplify the situation and vilify the student. This leaves us more likely to respond defensively, criticize, and engage in power struggles. Each of these instincts are likely to increase tension and escalate conflicts at the exact moment when we know that diffusing the situation would be more beneficial to our students and ourselves.

Connections enhance our ability to build relationships, work toward resolving tensions, and communicate with compassion.

The first segment of every workshop, conference, or institute we lead always begins with reflection. Whether we’re engaging in a protocol, a free share, or a conversation starter, we like to take a moment at the beginning of our learning experiences to stop, pause, reflect, and to find ourselves in the moment so we can be fully present.

At our last Chancellor’s Day event, Inspire, we offered four reflection-based workshops that focused on the day’s theme: see and be seen. These workshops invite educators to reflect on a connection they want to deepen — connection to self, connection to students, connection to colleagues, or connection to communities. Within this framework, educators have the opportunity to explore practical instructional strategies that can be used for students and adults.

Connecting to self

What are your core values? When have you been the happiest, the most proud, the most satisfied? Using this article from Mindtools as a reference, you can investigate patterns and trends in your life — patterns that may reveal who you are at your core. Identify your values, then prioritize them. What’s more important to you — accuracy or efficiency? Honesty or peace? Community or independence? This process of identification and prioritization helps you drill down to the values that drive your work, personality, and passions.

Connecting to students

The more experience we gain as educators, the farther apart we are in age from our students. Generational differences, cultural differences, stylistic differences, and even language differences can separate us from truly connecting. It’s valuable to take a moment to question the assumptions we have about our students, and to resist allowing stereotypes or cultural differences to define them. Once we can articulate ways in which we see students, we can begin to critically reflect on these understandings and how they might limit our perceptions of who are students are, and of who they could become. This insight gives us the purpose and the motivation needed to push into our classrooms with a clear intention to find more points of connection with our kids.

Connecting to colleagues

One of the biggest changes in schools over the last decade is a focus on teacher collaboration. From teacher teams to co-teaching, teacher-to-teacher collaboration is at an all-time high. But increased collaboration also creates space for increased tensions, miscommunications, and misunderstandings between colleagues. Dealing with these dynamics while also teaching a class is extremely difficult. That’s why it’s important to build empathy and understanding. Repurposing a high-leverage instructional strategy, the Body Biography, allows us to better empathize with our fellow educators. The Body Biography allows us to use different parts of a body to represent different aspects of a personality or different actions — what we write in the mind communicates what a person is thinking, what we write in the hand communicates what they’re doing, and so on. By using the Body Biography as a tool for understanding our colleagues, we begin to see people from multiple perspectives — and blank areas will reveal key characteristics that we may not know about the people who are working alongside us every day.

Connecting with community

New York City has many diverse and unique communities. The more we connect with the community we’re teaching in, the better equipped we are to build relationships with our students, parents, and the neighborhoods in which we’re working. We can start by making connections between our communities and their narratives. Draw a map of your school community. Annotate it to illustrate the people who live within the community, and the stories they have to tell. How would these stories differ if told from a person who exists outside of the community? The differences between these two narratives will help us to better understand the lived experiences of our students and their families, and be more aware when our experiences differ. These realizations can also help us to be more mindful and intentional in how we tell stories about our community to others.

Each of these reflective activities helps us to make connections between ourselves and others. It takes vulnerability and bravery to walk into these spaces, to confront stereotypes, and to reflect and revise our practices. But the benefits are worth the risks. These connections enhance our ability to build relationships, work toward resolving tensions, and communicate with compassion.

Teaching is a labor of love, but the love does always balance out the labor.

My understanding of what it means to be a teacher was reinforced by how the media portrays teachers in film. I wanted to be Michelle Pfeiffer, winning over the “dangerous minds,” or Robin Williams inspiring the overachievers with his progressive ways, or Morgan Freeman pushing the students to do the right thing, or Edward James Almos challenging his students to step up and become the academics they were. Each of these portrayals, all based on true stories, tells the tale of a teacher who gave everything they had to their students — and within two short hours, saved the day.

In reality, my teaching experience feels more like a dark comedy than a feel-good hero story. Teaching is a labor of love, but the love does always balance out the labor. At the end of the day, when our patience is out the window, and things keep piling on, we have to figure out what it means to be a teacher, a parent, a social worker, and a nurse, all at the same time. Teachers often find themselves wondering, is this what burnout feels like?

Emotional labor

Recent research has investigated the silent toll that those in caretaking roles, such as teachers, face. They call the phenomena emotional labor. Former teacher turned journalist Emily Kaplan says, “Teaching is all about reaching clear to the heart of another human being and using everything you’ve got to make a difference. It’s calming kids when they’ve had a rough recess, celebrating when they lose their first tooth, absorbing their struggles and their traumas, channeling their joy and investing the currency of your own emotions in an effort to help them grow." It’s the opposite of what we’re supposed to do on the airplane — we’re putting the oxygen mask on everyone else before we put it on ourselves. Researchers highlight that when society inevitably fails to provide students with what they need, teachers feel “personal and professional guilt, which they must suppress for the broader good. Emotional labor begets more emotional labor.” And this challenge is compounded even more because the only power we really have in the system is in the confines of our classroom. Educators feel pressed down and overwhelmed by systemic obstacles with no clear path forward. So where does that leave us? Brene Brown might suggest that it leaves us feeling disconnected and isolated. It leaves us searching for connection. Connection, Brene says, is "the energy that exists between people when they feel seen, heard, and valued.” Connection creates energy. When isolated and disconnected we feel tired, lonely, and potentially depressed. But opportunities for connection create energy between people. Within that space, we can “give and receive without judgment; and derive sustenance and strength from the relationship."

Connection as an antidote to emotional labor

So that begs the question — what makes you feel seen? We can come to some agreement that there are three simple ways we can see and be seen. The first is simply, to listen. David Augsburger says that “being listened to is so close to being loved, that most people cannot tell the difference.” Listening feels like love. How can we listen more intently? Who do you need to listen to you? Who do you need to listen to? Second is to reflect. To reflect is to go back, to see again. When we reflect what we’ve heard to someone who is sharing with us, we demonstrate that we see their perspective, even if it’s different than our own. If 100 people shared what each of them saw in a Rorschach test, for example, we’d get 100 different answers. Everything from a puppy to an ice queen to muddy footprints. When we are reflecting what we’ve heard, however, we don’t need to rush to share our own opinion, or how we perceived the situation, or give tips about how others can see what we see. All we need to do is reflect what we understand their perspective to be. Here we seek first to understand, and then to be understood. And finally, we want to acknowledge, in one way or another, that no one is in this alone. You are not alone. You may be teaching by yourself. You may be grading papers on your own. But you are not alone. A community of educators has a deep bench, and we are here to connect with you, to acknowledge your experience, and reflect on your experiences. This is empathy. And Brene Brown reminds us of the power of empathy, noting that when we express or open ourselves up to feel another person’s feelings, we are we are saying, “I know what it’s like, and you are not alone.” We know what it’s like. And we see you.

Breaking down the components of creativity so that we can begin integrating it into our instruction.

Some people have a true gift and talent for drawing, painting, sculpting, singing, acting or dancing. We sometimes mistake this talented artistry as creativity. This makes it seem like creativity is something you’re born with, not something you learn. But that’s a myth — there’s a big difference between artistry and creativity. Creativity is about developing the power to make something from nothing.

Our research-based framework for 21st century skills focuses on the creative mindset as one of five essential skills for the 21st century. Let’s face it, in a world where every piece of information is available to us within three clicks of a mouse or three swipes on a phone, finding facts is easy. The biggest needs we anticipate for future success is the ability to use information to innovate and solve complex problems. That takes creativity. As educators, it’s our job to figure out how to teach creativity to our students. In order to teach towards creativity, we have to disavow the myth that creativity is an innate trait bestowed on only the few, and begin breaking down its component parts so that we can integrate it into our instruction. We’ve defined creativity as the capacity for students to cultivate their curiosity by questioning or imagining in order to contribute positive improvements or inventions to their world. We’ve identified four skills that work together to cultivate creativity: imagining, questioning, simulating, and appreciating ambiguity.

Imagining

A vivid imagination is part of childhood development that is sparked around toddlerhood, as children learn about the world through play and pretend. To pretend that something is true, when it isn’t, for the purpose of exploration and understanding (as opposed to deceit — which would be lying, or as a joke — which could be satire). We've outlined three simple entry points to incorporate imagining into instruction:

These are not the only entry points, but they should be accessible to us at multiple levels of instruction, and across different content areas.

Questioning

Like imagining, questioning is also a normal part of human development that emerges as early as some children can talk (the classic, “why, why, why, why?”) and often lasts through early elementary school. Once in school, this skill often atrophies as traditional methods of teaching are structured such that the teacher asks the questions and the students answer, rather than having the students ask questions and work together to explore possible answers. Asking questions is a key factor of curiosity, and curiosity is a key level towards creativity and problem solving. Let's look at three entry points for supporting students to being asking questions, rather than simply answering them:

Simulating

Simulation or embodiments are powerful, physical ways to connect and internalize information though experiences. We will never know what it was really like to be on the Oregon Trail, or to fight in the American Revolution, or to live in a Hooverville during the Great Depression — but through simulated learning projects, we can approximate the experience to gain deeper insights. Whether we’re engaging in a short, impromptu learning activity, or a long term project, here are three entry points for simulating:

Appreciating ambiguity

Whether it’s nature or nurture, as human beings, we’re always looking for the right answer. And in school, we typically reward this kind of thinking. When students believe that there is one right answer, they may fall into the trap that being right is the goal of learning, when in fact, being right means we haven’t learned anything new at all. There is no absolute right answer in real life, and if we can shift our thinking from looking for the right answer, to looking for the possible answers, we shift the purpose of learning from something that is singular and narrow to something that opens us up to new opportunities. Entry points toward appreciating ambiguity:

When we regularly engage our students in lessons strategically designed to support imagining, questioning, simulating, and appreciating ambiguity, they become more and more connected to the topic, and more authentically curious about the process. Their imaginations are sparked with new ideas, innovative solutions, and new questions. Each of these traits works toward developing the mindset of creativity — resilient in the face of challenging circumstances, curious about the world, and confident that there isn’t any problem too big to tackle, or too simple to ignore.

What type of learning experiences do students need to lead in the future?

I recently provided the opening remarks for an institute with international educators about developing a 21st century pedagogy. As part of the talk, I wanted to draw a comparison between how I grew up and how kids are growing up today. I described how, when I was growing up, I had to use the card catalogue to find sources for my research paper, wait for film to be processed before I could see my pictures, and how I learned to type on a typewriter. These all seem like ancient technologies to us now, but it was a good reminder of how much has changed, and how quickly. The impact of these changes has made the world smaller, and more complicated as the advancement of technology has created more opportunities for globalization, instant communication with anyone in any time zone, and insights into the celebrations and challenges people experience around the world.

The reality is that the advancement of technology in the last twenty years has changed our culture in phenomenal and unpredictable ways, and we feel these changes acutely in schools. Whether it’s a challenge around developing and sticking to a cell phone policy for students, competing for time and attention in the YouTube generation, or how all of a sudden we find ourselves saying something like, “kids these days...” followed by something that was disappointing. As educators, we are confronted with the culture shift in powerful ways, and we know we have to do something about it. Many teachers, schools, and even districts have begun adopting the concept of preparing students to be global citizens as we recognize that students who are currently in 6th grade will be 25 years old in the year 2030, and that this generation of students will be the adults who deal with climate change, global economics, and the impact of massive voluntary and forced migrations. So the question becomes, what do kids these days need to learn and be able to do in order to feel prepared for the future where they will be leaders?

Using the Global Mindset Framework

This question is always a motivation for me to think critically about cultivating a curriculum with 21st century skills. In its current iteration, our research-based Global Mindset Framework includes 20 skills and capacities for global thinking that can be used to develop a thoughtful 21st century curriculum by transforming 20th century assignments into dynamic 21st century projects. Using the framework to guide or develop a unit plan or project can quickly transform our curriculum and instruction.

One way we can begin to transform our curriculum is by acknowledging that our current curricula are most often focused on a traditional 20th century set of thinking skills connected to Bloom’s Taxonomy (Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation). Even in spinoffs like Marzano or Webb’s Depth of Knowledge or our own Rigormeter, we see Bloom as the foundational underpinning of most learning goals, content standards, and teacher objectives. This is great, because teaching toward global citizenship or towards 21st century skills absolutely requires students to be logical, rational, and critical thinkers.

Small, deliberate changes

To begin transforming our curriculum, we’ll want to consider adding one new skill from each Mindset of the framework. By making small, deliberate changes to a simple task, we can transform a basic 20th century task into a dynamic 21st century project in a very short period of time. Our first step is to begin with a basic task that we have taught in the past, or one we’re thinking of teaching in the near future. Let’s imagine that we’re teaching middle school Science and are in the middle of a unit on the solar system. Maybe the students’ assignment would be something like this: compare and contrast the features of the planets. We can easily locate this task in the Critical Mindset with a focus on analysis. As we move on, we’ll want to add an element of the Collaborative Mindset. We can scan the list of collaborative skills and pick any one that seems interesting, relevant to the students or the task, or easily connected. For this example, I’ve selected multiple modalities. This means that students will work together and communicate their learning in different ways — through writing, speaking, drawing, and so on. How can they use multiple modalities to compare and contrast the characteristics of the nine planets? They could create a chart, use a program like Powerpoint or Google Slides to design a visual presentation, or they can present something aloud. That’s three modalities — that seems good. Next, let’s add a skill from the Creative Mindset, keeping in mind that creativity isn’t about artistic ability, it’s about the ability to innovate and develop something new. The skills within creativity help students to think in stages that build toward innovation and imagination. For our unit on the solar system, let’s select the questioning skill. How can questioning connect to students’ comparison and contrast of the solar system and a presentation? Well, maybe part of their presentation includes questions that they’ve asked and found the answers to. This is a good skill because it will help students to focus on key facts and create more opportunities for them to take responsibility for their learning. Next comes the Caring Mindset. We want students to be socially and emotionally engaged with themselves and each other, so we’re looking for opportunities to build these skills directly in our instruction. One element we can focus on is building confidence. It makes sense that if students are developing a project that includes an oral presentation, they may get a little nervous, shy or uncomfortable. That’s okay! We want to push students to be brave and confident, and school should be a safe place for that experimentation. As a teacher, I’ll ask myself — what I can build into the project that will help students develop confidence? With an opportunity to practice their presentation and get some structured feedback from another student on their team, they may improve their presentation skills and gain more confidence, and can reflect on their process (before, during and after the final presentation). Finally, we get to the Global Mindset. I'll go through the exact same process and imagine how I can connect a skill from this mindset with the task at hand. Let’s go with real-world problem-solving. Students may think knowing about the planets or doing a presentation is an unimportant assignment, but framing this as a real-world experience can make the topic more engaging, more interdisciplinary, and more relevant. We can make a connection between their work in the classroom and the work of individuals in various careers. We can offer a scenario to students that includes a role for them to play, an imagined audience to present to, and a real-world format where this topic would apply. For our project, let’s imagine that our students are Scientists and Engineers presenting their findings to the UN in an effort to complete an international space mission.

Our reimagined, 21st century project

Let’s look at how our project has transformed. When we started, our 20th century task was to compare and contrast the features of the planets. Our revised, 21st century task looks more like this: You are on an elite team of Scientists and Engineers who have been assigned the responsibility of developing a proposal for an international space mission to one planet in our solar system for the UN Assembly. As a team, you'll do the following:

This process can be used in any content area and is a fantastic way to explore the transition from 20th century to 21st century learning. As educators, we have a special opportunity during this unique time period to think deeply about today's students as tomorrow's leaders. What type of learning experiences do they need to lead in the future?

Opportunities for micro assessments that ensure students are developing the skills needed to overcome academic obstacles.

We often think about learning like a marathon, as if it's this long, long race where everyone begins at the same starting line, sets their pace, and runs at that pace for a long time until they arrive at the finish line. But there’s a problem with this analogy. The problem is that learning does not typically happen in consistent, incremental stages. Instead, learning happens in fits and starts, and in the best situations, it is the result of being deeply curious about a subject, topic, or theme and engaging in a productive intellectual challenge. In fact, when we really get down to it, learning isn’t like running a marathon at all! If learning is like running, then it’s probably a lot more like jumping hurdles.

When jumping hurdles, runners begin at the starting line and then sprint as fast as they can towards the first obstacle they have to overcome. If they’re successful, they continue to sprint forward. If they are not successful, the hurdle falls down, or worse — they fall down. Then they have to pick themselves back up and start again. Runners who can overcome all of the hurdles sprint through each stage on the track. Runners who cannot fall behind abruptly, and sometimes, permanently. To train runners in hurdles, coaches help them practice by providing a set of smaller obstacles along the track, and train them through practice sessions where they develop specific strategies that will refine their skills. Coaches watch the moves the runners make while they’re jumping, and study these moves to give the runners actionable feedback about ways they can adjust their footing, their stance, and their speed — all of which help them to become better at the sport. This is the same kind of training and support that checks for understanding provide for students.

Micro assessments

Checks for understanding are micro assessments that teachers can build into their lessons to ensure that students are developing the strength, skills, and strategies necessary to overcome the academic obstacles that will be presented in a long-term project, assessment, or high-stakes test. They are mini-hurdles that can help a teacher determine which students are sprinting ahead, which have minor gaps in understanding, and which are struggling to make sense of the lesson content or skills. Traditional instruction organizes the procedure of a lesson so that the teacher presents on the important topic of the day, the students engage in practice related to that topic, and then go home. Everyone holds their breath and hopes that the students do well on the quiz at the end of the week. In our analogy, this model would be equivalent to a coach turning away from a race, hoping their runner is able to finish. Students, like runners, need three things from their teachers to increase their speed, strength, flexibility, and stamina. 1. Tasks that gradually increase in difficulty Like a coach who lays out smaller hurdles on the track to teach runners about basic techniques, teachers can provide short tasks for students at strategic points in a lesson. One simple structure for a lesson would be to include one check at the beginning of the lesson, one in the middle, and one at the end of the class period. The opening check serves as a baseline understanding of what students remember from a previous lesson, and assesses their prior knowledge or current thinking about a topic. The mid-lesson check becomes a moment to micro-assess their understanding of the essential learning of the lesson. What must students understand in order to meet the learning target or objective? Finally, an end of lesson check gives us vital information about how students are leaving the class. This check informs our instruction for the next day’s lesson. 2. Actionable feedback for micro adjustments We often assume that assessments always equal grades. But just like not all runs are races, not all tasks need to come with the heavy weight of a graded assignment. Small and simple assessments designed as checks for understanding provide key insights into students’ knowledge while it’s in formation. This is critical to helping teachers understand how students are making meaning, as well as how they’re interpreting (or misinterpreting) the content. Rather than focusing on how many points to provide, consider ways of providing students with actionable feedback that includes micro adjustments. Micro adjustments may include offering students a suggested next step, pointing out something they did well, or giving a tip as to what would have made their response more complete. The goal is to move away from evaluative feedback like “good job” or “needs work” and move into actionable feedback, which gives students a concrete next step to practice. When we get good at building checks for understanding into our lessons, we can design our lesson sequence to build on the feedback we give students in the moment. 3. Celebration of progress As many runners can attest, marking personal progress is critical to building confidence even when someone else crosses the finish line first. As educators, it is essential that we are able to note specific areas of improvement for students at all levels. We can make connections between their gains and future successes, which increases their investment in their learning and can help them to set short- and long-term goals.

Getting started

There is no shortage of strategies for checks for understanding. Below is an example of one of our favorite sequences using US Government as an example topic.

There are countless ways to monitor our students’ learning. When we are engaging in beginning, middle, and end of lesson checks for understanding, we have so many opportunities to notice our students’ process and progress, to reflect with them, to encourage them, and to help them leap over the obstacles they encounter on their learning journey.

A three-step process for unpacking and implementing a pre-packaged curriculum.

A well-developed and effective curriculum is the cornerstone of an excellent education. Many schools go to great lengths to ensure that they can identify a highly-rated curriculum on behalf of their students. This often means spending a great deal of money to purchase a complete, professionally-designed curriculum which may include textbooks, web-based resources, unit plans, scripted lesson plans, and student-facing resources.

But there’s a big difference between having the curriculum and teaching the curriculum. It isn’t as simple as reading aloud from the Teacher’s Guide. Unpacking a pre-packaged curriculum takes focused and continuous effort on the part of teachers and their whole school community. When we work with schools who are implementing a new curriculum, we advise using a three-step process: adopt, adapt, apply.

Adopt

The curriculum is the driving force behind the teaching and learning within a course. Whether a school is moving from one curriculum to another, or moving from teacher-designed to a pre-packaged curriculum, there’s a lot of work that goes into adopting something new. We encourage school leaders and teachers to unpack the curriculum materials by focusing on three main pieces — structure, key components, and tensions — and making connections to current instructional practices, student culture, and school climate.

Adapt

Even the very, very best curriculum cannot be used straight out of the box. For a curriculum to be highly effective, it must be adapted to meet the needs of students, the style and personality of the teacher, and the mission and vision of the school community. After taking time to understand the curriculum’s structure, key components, and tensions, we’re ready to begin making adaptations.

Apply

After adopting the curriculum by unpacking its components, and adapting the curriculum to meet the needs of the community, educators will feel more confident to begin implementing the curriculum.

Curriculum design is an intensive and demanding process. Schools and districts can save teachers time by investing in high-quality curricula that allows teachers to focus on implementing instruction rather than on curriculum design. But in the process, we must remember that it isn’t as simple as pulling it out of the box and reading aloud from the book on the day of the lesson. School leaders will want to create space and time for teachers to analyze the adopted curriculum, make adaptations necessary to meet students’ needs, and apply it in their classes after critical reflection and opportunities for revision. Following through with these practices will ensure that the curriculum is being implemented with fidelity, integrity, and authenticity.

The pressure to plan your curriculum it in just the right way can be overwhelming. How can you make sense of the process?

By ROBERTA LENGER KANG

When the back to school sales are at their peak, students and parents are picking out the cutest notebooks and the coolest backpacks. Meanwhile, educators are feeling the pressure and anxiety that comes with the start of the school year — particularly as they think about their curriculum. Different school communities and districts have different approaches to designing curriculum. Some purchase big box curriculum sets with prescribed lessons, while others have the opportunity to design their own, which can be exciting — and also a bit daunting. Cultivating a course curriculum is one of the most important and most complicated tasks for educators. It requires deep content knowledge and an accurate anticipation of student ability throughout the school year. Teachers need to differentiate the most important content and the most important skills in the most effective sequence — all while knowing that the decision to teach one thing is also the decision not to teach a hundred other things. The pressure to plan it in just the right way can be overwhelming. This process will always be a challenge, but it doesn’t have to be painful! In our curriculum-focused coaching projects, we support educators as they examine, design, implement, and refine customized or adapted curricula. Each educator and classroom is unique, but curriculum planning often brings up common questions. Below are some of the most frequently asked questions we hear from educators as we support them in the planning process.

What goes into a curriculum map?

A well-developed curriculum map should provide an overview of the course at-a-glance. Maps are most valuable when they include a clear picture of the course goals, how those goals intersect with the content knowledge, thinking skills, relevant standards, and a plan for assessments. Here’s a good checklist for a curriculum map:

What’s the difference between a curriculum map and a unit plan?

A curriculum map provides an overview or summary of the course, while a unit plan provides the details needed to develop each individual lesson. A unit plan may include specific resources to use in a particular unit, a pacing calendar that outlines the learning goals for each week or each day, lists of vocabulary words, and a plan for differentiating instruction for different learners. Unit plans tend to be longer and include more explicit plans that illustrate the arc of the unit and provide the necessary details to develop daily lesson plans. There is a critical distinction between the curriculum map as an overview and the unit plan as the detailed guide to support lesson planning. Curriculum maps that include unit plan-level details often become massive documents that are difficult to read. They can become a dumping ground for edu-speak-jargon that doesn’t really mean anything. As educators, we want to remember that these documents are tools to support and facilitate our planning process. If they don’t do that, they aren’t ultimately very valuable.

How much detail should be included?

When it comes to the curriculum map, we want to include information clearly and succinctly, which means we can eliminate jargon or unnecessary details. For example, it’s valuable to list relevant standards on a curriculum map because it will give a picture of how all standards are being addressed throughout the school year and how they’re sequenced within each unit. However, standards often have a lot of very specific, formal language. Simply copying and pasting the entire standard into the curriculum map is thorough, but not always helpful. It isn’t reasonable to expect that anyone will read with that level of specificity, it isn’t particularly helpful to teachers who need to see these standards broken down in the unit plan, and it can become extremely repetitive if the units utilize the same standards. In these situations, we recommend using the standard code, and summarizing the standard in a short phrase or sentence. This provides a simple and clear alignment with the standard, demonstrates the educator’s understanding of the standard, and keeps the information focused and clear. The same rule can be applied in other categories as well.

How should the map be formatted?

Formatting is often a personal choice, and different people prefer different styles. We recommend using a horizontal chart with a column for each critical component, and a row for each unique unit. The value of this format is the at-a-glance nature. If we can read from left to right along a row, we’re getting an overview of each unit in the course. When we can complete the curriculum map in 1-2 pages, we get a good picture of the course goals and the sequence of learning the students will experience. This allows the curriculum map to act as a touchstone planning tool for teachers, and becomes a great document to share with school leaders, parents, and even students.

Can curriculum maps be changed?

One of the things that makes writing curriculum a daunting task is the sense of its permanence. It makes sense to want to keep the curriculum fluid, as the most effective teaching is influenced by a wide range of variables like current events, student cohorts, and shifts or changes in the field. The fear of permanence can often become a justification for not creating a curriculum map. But the benefits of long-term planning, for teachers especially, cannot be underestimated. The most effective curriculum maps are living documents that provide planning support to teachers throughout the year and communicate the intentions of the course to others (administrators, parents, students, other teachers). We recommend that teachers regularly reflect on their lessons and unit plans as they’re implementing the curriculum so that they can make adjustments, remember what worked and what didn’t, and update the curriculum as necessary. We revisit our curriculum over the summer or at the beginning of the school year to account for the learning of the previous year.

What are the steps I should follow to make a curriculum map?

In the curriculum mapping process, we see a relatively consistent approach that favors backwards planning, which suggests that teachers should first determine the end point (the ultimate goal or final assessment) and then plan backwards from there. This process is meant to create a clear alignment between content, skills, and instruction. If this process works for you, use it! The problem is that this process doesn’t apply to all teachers or all situations. When it doesn’t work, it can create major obstacles in the development process. Our recommendation is to start with what you know, generate your ideas based on any entry point you can find, and fill in the blanks along the way. Then, reflect and revise on the plan from an alignment perspective to ensure that the planning process maintains instructional integrity.

If we want to ensure that our students are developing the skills needed for the next hundred years, we must begin considering a new pedagogy for a new era.

When I was in high school, my English teacher, Mrs. Horn, required her students to write a research paper. This process included daily trips to the school library, where I used a card catalog to look up the name of a book that may, or may not, have the information I was looking for. Once I found a book in the card catalog, I had to hunt for it using the Dewey decimal system, locate the book, and then begin searching for the basic facts about my topic. Mrs. Horn was a stickler for notecards. Our research papers needed to have 75 accompanying index cards so that we could organize our information one fact at a time, before typing it out on the word processor or typewriter.

How times have changed. Most school libraries today have more space dedicated to technology than books, and the long process of searching through dusty publications or old-timey microfiche has become a thing of the past. But here’s the thing: the importance of research papers hasn’t changed. And the importance of research hasn’t changed. What has changed is our access to information.

Shifting educational landscape

The radical advancement of technology and the internet has fundamentally changed our relationship with information. A 20th century education taught us how to find information — but finding information is no longer a problem. If anything, in the 21st century, we have access to too much! With hundreds of thousands of hits through internet searches and recommendations for related information, the question is no longer how to find the facts, but what to do with the information that’s literally a click away. How do we interpret this information? This is the question that teachers and school leaders struggle with as they attempt to make key concepts relevant to children in a rapidly changing world. These advances in technology have not only changed our relationship to information, they’ve changed our relationship to other people. Instant connection, instant messaging, and instant information-sharing have changed the landscape of interactions.

Educating students for tomorrow, today