|

Creativity flourishes in an environment where exploration is encouraged and individual voices are celebrated.

Genre-based writing is the art of crafting narratives within distinct literary genres or categories. Literary genres, such as fiction, non-fiction, poetry, drama, science fiction, fantasy, mystery, and romance, are defined by specific stylistic elements, forms, and content.

Engaging in genre-based writing involves intentionally aligning one's writing with the conventions, themes, and structures associated with a chosen genre. This process includes utilizing storytelling techniques, incorporating stylistic elements, and exploring themes relevant to the selected genre. For instance, a mystery novel might feature a central crime, a detective, and a resolution, while a romance novel centers around a key romantic relationship within the plot.

Why genre-based writing matters: a deeper exploration

Recognizing the significance of genre-based writing goes beyond the conventional understanding of major genres such as narrative, argumentative, and informative. It involves delving into the unique sub-genres, including speculative memoirs, flash fiction, Ted Talks, infographics, Op-Eds, and more. This exploration involves immersing oneself in an inquiry-based study of specific texts, a process that reveals nuances that often transcend traditional genre boundaries. Within this exploration, the promotion of creativity takes center stage. By encouraging students to engage with diverse sub-genres, teachers foster an environment where creativity can flourish. This approach not only sets clear expectations for writers, but also enhances their ability to communicate effectively with their audience. In doing so, it allows readers the freedom to choose works that are tailored to their preferences, fostering a deeper connection and appreciation for the art of writing. The Student Press Initiative (SPI), a signature initiative at CPET, strongly advocates for genre-based writing as a meaningful framework that not only expands literary possibilities, but also nurtures the creative spirit within each student.

What does genre-based writing entail?

SPI serves as a guiding force for both teachers and students in the realm of genre studies, employing a close examination of exemplars — often drawn from a diverse array of published texts, ranging from poems and essays to PSAs. In this process, students engage in a detailed analysis of these texts, examining content, structure, and craft through the lens of a writer, taking in all of its attributes and conventions in the process. The collaborative nature of this exploration lays the groundwork for creativity. Through shared discussions and the creation of charts, students collectively share insights into the genre and its unique characteristics. Rather than prescribing what or how to write, teachers adopt an empowering stance, encouraging students to explore and discover, thereby nurturing the development of insightful ideas and observations. This student-driven approach not only empowers individuals but also transforms the teacher's role from knower, to that of a facilitator or provocateur, cultivating a powerful space for exploration, self-discovery, and creativity. In a recent workshop I facilitated, SPI coaches immersed themselves in a genre-based study of the poem "What For" by Garret Hongo. While I’ve used this poem many times on many different occasions, I’m always impressed by the new ideas, observations, and questions that arise, underscoring how readers engage uniquely with texts. Collective discussions delved into content, form, and structure, highlighting original stylistic moves by the author. For instance, one coach noted changes in stanza lengths, sparking a discussion on its intentional contribution to the poem's meaning. Another coach made note of his powerful auditory imagery, and another made content connections to the American Dream. This exploration set the stage for coaches to embark on their own creative journeys, crafting "What For" poems inspired by Hongo's content, form, and craft, including elements such as repetition and reiterated structures. Reflecting on the similarities and differences among these poems further deepened the collective understanding of this specific genre, demonstrating how creativity flourishes in an environment where exploration is encouraged and individual voices are celebrated.

Unleashing creativity and self-discovery

In summary, genre-based writing is a powerful tool for creativity, independent thinking, and self-discovery. Embracing this approach turns educators and students into skilled explorers of various literary genres, creating a collaborative and empowering learning space.

Promising practices that can help nurture confident, capable student writers.

The beginning of the school year is a powerful time for setting intentions and establishing expectations. As a former classroom teacher and professional development coach, I understand the importance of making sure students feel safe in their writing environment, so that they feel empowered to put pen to paper. Using the beginning of the year to create a culture of writing can help cultivate a sense of community, boost students’ confidence, dispel some of the myths that exist about writing, and strengthen students’ skills and strategies.

How then, can we create this culture and community?

Creating the environment

As Dan Kirby writes in Inside Out: Strategies for Teaching Writing, “…there should be some obvious indications that you believe that the physical environment is important, and these touches need to be present even in a rather sterile classroom setting…the fact that you’ve done something to your room is a signal to students that you care about the writing environment.” Teachers should create a space where they want to be, as chances are that the students will feel comfortable, too. Teachers can use questions such as:

By asking and answering these questions, it can inform and inspire the ways in which you design your classroom, as well as what materials or resources you might need or want. Perhaps you want to have a writing corner, or a gallery space for finished pieces. Think about all the spaces in the room — whether it’s a specific bulletin board, the walls, the ceiling, outside the classroom — where and how will writing be honored and celebrated? When it came to my environment, I recognized the importance of a quiet, comfortable space for students to write. I wanted to have inviting spaces around the room where students could choose to sit, whether it was on the carpet, with a pillow, a large bean bag, or in a comfortable chair near a window. In addition, I would turn off the lights when we wrote and play soft, classical music. This routine, over time, helped signal to students that it was time to write. It set the expectations that when we write, it's quiet and calm. You might be thinking that this can or should only happen in an elementary classroom; however, I have seen it used in middle and high school classrooms, and it was very well received by the students. I also had a writing center in my room, where students could go to gather paper, pencils, highlighters, and post-its to use for their writing. There was a basket for them to drop writing that they wanted or needed me to read. This empowered students to take ownership of their writing and build their independence as writers by providing them with common resources and tools they could access on their own, as needed.

Establishing rituals & routines

The second promising practice for creating a writing culture is to consider meaningful rituals and routines that value and encourage writing. Rituals and routines involve necessary actions that create purpose and organization, and when done frequently, they become innate. Below are some of my favorite rituals and routines.

I encourage you to start the process of creating a culture or writing by identifying what you are most passionate about, what you are most excited about, and use that information to inspire the ways in which you create your space and establish your rituals and routines. If you have a passion for writing, like me, and/or you are a writing/ELA teacher, then I invite you to use the promising practices shared above, as they were very helpful for me and for the advancement of my students as writers!

Help students gain awareness of and ownership over their own learning.

When we ask our students to write reflectively on a topic, we are asking them to think about the topic, and put that thinking on paper. This seemingly small ask can have big effects, including an increased awareness of one’s own thinking and learning.

Why might you ask students to engage in this process? As Dr. Saundra McGuire, LSU chemistry professor and learning expert explains, “learning is about being able to explain something and apply it in other ways.” Reflective writing, then, is a way for students to bring their knowledge to the forefront, creating space for them to explain their ideas and apply them in ways beyond the immediate context. For example, when we are reading a challenging class text in English, such as a Shakespearean play, we want our students to do more than read and interpret that particular Shakespearean text; instead, we want them to have an awareness of how they are reading that play in order to later apply those same reading dispositions to another challenging text. The more we can help our students understand their own metacognition when reading and learning, the more ownership they have over that learning. This is empowering for our students. Teaching students to be aware of their thinking is the first step in reflective writing — and with this awareness comes the ability to apply thinking patterns to other arenas.

Introducing a double entry journal

When we ask our students to engage in reflective writing, we are trying to peek inside their minds to check if they are understanding key concepts, but also we are trying to help them name their own thinking moves. This is why writing to learn is such an important practice in our teaching — we are using writing as a reflection tool to make students’ thinking visible. In my two decades of teaching, I’ve seen more graphic organizers than I’d care to admit, and in the end, I always return to the double entry journal when I need students to respond to a text in a reflective way. The double entry journal is the most simple graphic organizer imaginable to help students focus on a particular text, and encourage their thinking around that text. The goal of the double entry journal, circling back to McGuire, is to be able to explain the text and apply it. Keep in mind, when we say “text” it could be a broad use of the term, including math problems, an historical event, a quote from a text, an image, etc. In an article I co-wrote with Jacqui Stolzer, a fellow K-12 coach, we discussed how “double entry journals include two components: a column on the left, partially filled out with quotes from the text, and a column on the right, which is open for viewers to share their thoughts. Returning to the ideas presented in UDL [Universal Design for Learning], a double entry journal that includes specific lines from the text is useful for students who have central executive challenges, but in reality, everyone can benefit from the text references.” While the double entry journal is a template for reflective writing, teachers can differentiate this tool by pulling out specific quotes for students, or by giving students free reign to respond to quotes that strike them.

Modeling the double entry journal

Below is an example of a double entry journal that I wrote as a way to show my thinking about a text. In my entry here, I share a quote in the left column that I find provocative, and in the right column, I unpack what it means to me. A student reading this double entry journal might be surprised by all of the reading thoughts I have after reading Bateson’s brief line, but this is the point! We want students to see that my brain is active when I am reading, and in this example I am trying to name some of the thinking moves I am making as a reader.

After sharing a double entry model like this with students, I would ask questions such as: What do you notice I am doing as a writer in my double entry response? What moves am I making? My example is a bit of a stream of consciousness, and this shows students how I can engage with a text in complex and somewhat messy ways. And that is okay! Writing, learning, and reflecting tend to be messy and nonlinear paths. While students may not write as much as I do in the example above, offering them an advanced model can demonstrate the possibilities and multiple ways in which they can respond to a text using this format. Writing your own model for your students and asking them to notice and name the different ways you responded to the text can be instructive in two ways: students are able to see what we mean by “reflective writing,” and they will glean more understanding of the text through your reflective writing.

When students are asked to write a response to a quote, an equation, an historical event, or a math problem, they have to find something to say. They have to breathe life into that text — both to help themselves understand it more, and to realize how it changes and influences their perspective. This is how reflective writing is a useful tool; it is a type of writing that nudges students to notice what they are thinking, and to document it for others to see. By naming what they think, students are also teaching themselves what they know, and owning their own questions.

Incorporate PBL into existing tasks and create engaging, meaningful opportunities for your students.

Project-based learning is a widely used term in education. Although many educators have a general understanding of what it means, it’s often met with uncertainty and apprehension.

A simple Google Search of “project-based learning” results in 10 pages of articles or blogs, written by various organizations, institutions, and individuals. For instance, cultofpedagogy describes project-based learning as a combination of standards, best practices of UBD (understanding by design), and formative assessments. ASCD describes a project as meaningful if it fulfills two criteria: that students "feel the work is personally meaningful, as a task that matters" and that the project fulfills a “meaningful purpose.” Edutopia describes project-based learning as learning that tells a story. Throughout my 15 years of teaching and coaching, I’ve seen varying interpretations and implementations of project-based learning myself, which have been further complicated by the move to remote and blended learning environments. For educators who are working with packaged curricula, it can be especially difficult to see the opportunities available for introducing PBL in classrooms. But focusing on the core components of this work can support us in establishing engaging, meaningful, and doable project-based learning experiences for our students.

Components of project-based learning

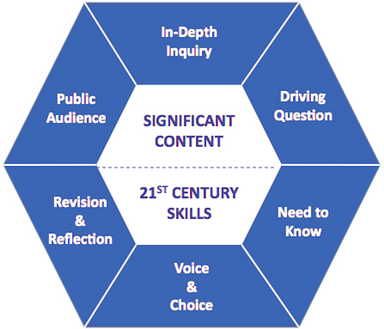

One of the most well-known and admired institutions when it comes to project-based learning is the Buck Institute. They offer what I think are very helpful criteria to inform what project-based learning can look like:

In line with much of the graphic, our K-12 coaching team believes that projects are a wonderful way to help students cultivate 21st century skills, focus on a pressing topic or issue, develop their identity as readers and writers, and engage in a writing process that involves extensive feedback, revision, and reflection on their learning. We believe the pedagogy of project-based learning is about:

Now that we’ve laid out some of the basics, we can investigate what project-based learning might look like in action. The questions above can help inspire task revision and allow you to incorporate project-based learning into pre-packaged curricula, without starting from scratch.

Creating relevant, meaningful tasks

Recently, I partnered with a school in Brooklyn to support them as they designed and reimagined assessments for online learning. As an elementary school, they had adopted a packaged curricula for English Language Arts instruction. My goal was to help them make existing tasks and assessments more engaging and relevant for students, and support them in redesigning the tasks as they were written in order to infuse elements of project-based learning — without compromising rigor. We began with a first grade writing task that focused on persuasive reviews based on favorite places, foods, etc. To begin revising this task, we started by examining three important questions, informed and inspired by the Buck Institute:

We used these questions to guide our analysis and revision, referring back to the original task:

Turning the task into a project

Now that we have been able to identify the basic possibilities and challenges with this task, we can continue on to revision, and begin to shift our original task into a project. When it comes to developing authentic and meaningful projects, we like to turn to a promising practice called GRASPS. This stands for: G: What is the goal of the project? R : What is the role of the student? A: Who is the audience? S: What is the structure of the writing? P: What is the purpose? In conjunction with our earlier questions, the GRASPS framework is a helpful tool in redesigning tasks and ensures that our revisions are clear. In our example, the responses look something like this:

Equipped with these revisions, we can now more easily shift the original writing task to one that is project-based, and understand how we can introduce these ideas to students. This not only generates excitement for students, but teachers as well — our partners in Brooklyn were eager to plan and implement this project within their classrooms, and were excited about the additional possibilities for creativity.

What I hope is evident throughout this process is that project-based learning can have a variety of entry points — whether you’re teaching remotely or in-person, creating your own projects, or reimagining pre-packaged curricula. Regardless of your situation, recognizing how instruction can be meaningful, relevant, and doable — even with the current parameters of teaching and learning — is possible.

Writing for publication can create awareness, raise social consciousness, and provide students with essential life skills.

When a student writes for publication, there is a shift in the dynamic between the student and their work. Picture yourself asking a student whether or not they spent a significant amount of time on their writing, only to have them respond, “Why would I spend time on it? It’s just for you.” In contrast, consider a student, who previously considered himself anonymous, telling his teacher, “Mr. Nick, I’m famous now!” after the book he co-authored with his classmates was published. Two very different reactions to a writing experience. How do we understand these two contrasting responses from young writers?

Founded in 2002, the Student Press Initiative (SPI) was designed to develop, foster, and promote writing across the curriculum through student publication, and revolutionize education by advancing teacher leadership in reading and writing instruction. Students transition from “writing for their teacher” to writing for an audience of their choice. To date, SPI has published over 850 books representing the original writing of over 12,000 students. SPI’s core values — project-based instruction, real-world authorship, community of learners, and celebrating student voice — resonate throughout these books. The grounding of these values raise the bar for what, how, and why students write.

Project-based instruction

We believe in using publishing for a real-world audience as a means to design and shape curriculum and expectations, as well as promote student engagement. We employ a backwards-planning model, where a final product is used to form an infrastructure for classroom instruction and activities. Through inquiry of the specific requirements and expectations of each project, teachers and students can better articulate the behaviors, artifacts, and customs necessary for the successful completion of the project — and being that publishing a book is a shared experience, students work together to support and encourage one another in new and powerful ways. Publication projects help to shape the culture, rituals, and routines that take place in the classroom. At the start of a project, a large calendar often overtakes the walls of a classroom, and teachers and students work together to identify the genre, audience, and purpose of their project, as well as establish details and deadlines. This helps establish a strong sense of community and collaboration. This is project-based learning at its best!

Real-world authorship

Real-world authorship shapes our approach to teaching and learning. Whether the audience is a class of incoming freshmen or first-year teachers in training, we work to connect young writers with actual readers. In the SPI model, classrooms become publishing houses in which teachers and students collectively shape an editorial vision. By exploring questions, issues, or concerns that exist in the world, their community, or within a specific content area, teachers and students collaborate to define a meaningful genre, theme, and audience. Writers then work to understand the expectations of their audience as they craft pieces with real readers in mind. No matter the content, there is always a real-world model that can demonstrate student learning with panache and voice that will engage readers. Through participation in a publication project, students develop skills and processes similar to those of professional authors. Students are supported through pre-writing and a gathering of ideas, drafting while consistently revising and editing, and finally, publishing, where they format and polish their writing to prepare for publication. Students experience “real” expectations and deadlines for publishing their book. Through these experiences, a strong sense of excitement, energy and urgency emerges.

Community of learners

SPI challenges traditional notions of “experts” in the classroom. Inspired by the work of Lave and Wenger (1996) and what they call “communities of practice,” we aim to cultivate students’ sense of expertise as writers by engaging in processes such as thoughtful inquiry of mentor texts, peer review, and peer editing. Through such processes, teachers and students work to establish a community of writers, consisting of many experts and many resources for learning and growing as authors. We encourage teachers and students to engage with a variety of texts as they begin to define qualities and attributes of powerful writing. As students learn the skills needed to write successfully, they also become experts in the project’s central theme as they read mentor texts, break genres down into smaller components, and ultimately, craft pieces that represent their learning and culminate in a final publication. A project designed around an in-depth genre study and inquiry invites students into a shared experience, and allows teachers to craft a thoughtful curriculum that addresses specific content and skills.

Celebrating student voice

Every student has a unique voice. Rather than celebrate the work of select students, we aim to celebrate the work of all students, using publication and celebration as a way to leverage and encourage participation. We believe every project should culminate in celebration — whether teachers and students decide to host a large-scale public reading at a local bookstore, smaller readings at locations such as their own school auditorium or classroom, or virtually with classmates, families, and friends. Celebrations — no matter their size or format — are powerful and rewarding experiences, and allow students to proudly share their writing with their community.

Writing can serve as a tool for creating awareness, raising social consciousness, and providing students with essential life skills. Our core values change the perspective and perception of writing for students around the world. These values, deeply embedded in our publications, reflect best practices for teaching writing in the 21st century, and help prepare students to succeed in lifelong learning.

To learn how you can partner with the Student Press Initiative and bring your students' writing to life, please reach out to us here.

Although personal, expressive writing is not necessarily a measurable outcome of learning, it is possibly some of the most important writing that we can ask students to do.

“Writing to learn” is a powerful concept that has long been espoused by literacy educators. In practice, writing to learn includes low-stakes writing assignments that generate authentic responses to prompts on a variety of topics. The goal of writing to learn is simply to unpack a subject, and the primary audience is the writer him/herself.

Some of the most powerful writing to learn practices include personal, expressive writing that allows us to reflect on how we are feeling and thinking. This may take the form of quick-writes in response to a question, journal entries, or letters to ourselves and others. Although personal, expressive writing is not necessarily a measurable outcome of learning, it is possibly some of the most important writing that we can ask students to do. Personal writing not only helps students develop their voice, but offers them precious space to reflect and process their feelings and thoughts, in order to feel emotionally strong and balanced. James Britton adds that expressive writing helps students academically, to “discover, shape meaning, and reach understanding.” As we plan instruction, whether remote or in-person, creating space for expressive writing is crucial, especially during times of crisis or change. During the remote learning period that has surfaced due to the COVID-19 crisis, teachers and schools across the world have worked overtime to reach and engage their students. Yet, even in cases where students appeared to have adequate access to digital devices, attendance was often lower than usual, particularly in middle and high schools in low-income neighborhoods.

Prioritizing mental health

When Principal Dr. Charles Gallo and his team at the New York City Charter High School for Computer Engineering, and Innovation in the Bronx — where I partner as an instructional and curricular coach — questioned students and their families about their low attendance, students reported feeling isolated, unmotivated, and in some cases, depressed, despairing, or scared. Dr. Gallo realized that his students’ social-emotional health and well-being needed to be tended to first. His students weren’t learning if they were not engaged, and they couldn’t engage if they were scared, depressed, or lonely. Swiftly responding, Dr. Gallo encouraged teachers to use their professional judgement to deviate from their planned units and lessons to prioritize students’ mental health and engagement by offering students opportunities to reflect and process their emotions and experiences around the pandemic. Encouraged by their principal, AECI faculty incorporated journal writing into their classes, which eventually evolved into plans for a schoolwide interdisciplinary project, grounded in personal, reflective writing. Students would craft responses to relevant essential questions, such as: How has the COVID-19 crisis had an impact on your personal life? How has it had an impact on society? What do you propose to solve or address the crisis?

Digital opportunities

In a digital world, where distance may make it challenging to interface with each student and check in about how s/he is doing, online options — such as Google Docs and Padlet — offer valuable asynchronous opportunities to read and respond to student writing with advice or supportive words. While sharing personal writing online demands trust and confidentiality, some students have shared that the experience of writing into a Google Doc (as opposed to a notebook) makes them feel braver. For students who don't have access to devices, journaling in a notebook or on paper is a terrific low-tech option for reflection. Incorporating these practices into your lessons can be as simple and informal as asking students to respond to a prompt that connects with the day’s topic. If you want to dig in further, consider some of these ideas:

An entrypoint to abstract thinking

Dr. Gallo and his faculty first incorporated journaling into their instruction as a way to help students process and express their complex and troubling feelings. Expressing oneself through writing (whether on paper, by typing a note on a phone, or working within a Google Doc) allows us to identify and understand our thoughts, which in turn, helps us become more confident, calmer, and balanced. When we reflect on and process our thinking, we can also start to make crucial connections to comprehend more abstract concepts and ideas. This is how learning begins to happen. At AECI, students’ responses to how has the COVID-19 crisis had an impact on your personal life? became an entrypoint into an exploration of the more abstract second part of the essential question — how has the COVID-19 crisis had an impact on society? In Math and Science classes, students used their writing as a springboard for interpreting data that showed how COVID-19 affected their communities. In History classes, students connected the current pandemic to the Black Plague and the 1918 Spanish Flu, using resources such as historical journals, information from the New York Times, and the Smithsonian.

A call to action

Following their investigation of the connections between personal experience and the societal impact felt by COVID-19, AECI students began to address the final essential question: What are your recommendations for addressing or solving the COVID-19 crisis? In keeping with the stages of Karen’s Hesse’s Depth of Knowledge framework and CPET’s Rigormeter, students moved from exploring their concrete realities to analyzing data and evidence, developing their own theories, and, finally, proposing a call to action. The project at AECI will culminate in a schoolwide portfolio of student writing and artwork, as well as letters to politicians that will incorporate supporting evidence from each discipline and propose solutions to elements of the COVID-19 crisis. Although AECI is focusing specifically on COVID-19, this type of interdisciplinary project can work for any relevant topic that’s applicable to your community.

For many of us educators, the demands of content, testing, or curriculum can leave us feeling as though we don't have time to incorporate personal writing into our lessons. However, when we recognize the benefits that come from creating space for students to make sense of their thoughts and feelings, we can see how this work is essential to student engagement, and how it can support the introduction of new content. When students feel emotionally balanced, personally engaged, and connected to a topic, real learning can happen — during times of crisis and every day.

Support students in establishing their voices as writers while advancing teacher leadership in reading and writing instruction.

Student writing is often read by one person (a teacher), and for one reason (a grade). But what if it could be different?

Through our Student Press Initiative, we seek to engage students in writing projects that culminate in print-based publications. These publications are designed for specific audiences, shaped around specific genres, and become widely accessible to their school community and the general public. This process not only helps students to establish their voices as writers, but helps revolutionize education by advancing teacher leadership in reading and writing instruction.

Raising the bar for student writing

Though each publication is a unique reflection of its student authors, the five phases of our publication process remain constant:

Publication in action: personal narratives from the Bronx

This spring, we supported 9th and 10th grade Special Education students at the Bronx High School for Business (BHSB) through this process. Their teacher was eager to introduce a project that would provide her students the opportunity to share a meaningful experience through the writing of a personal narrative or poem. With this in mind, our coaches worked alongside the teacher and her students to facilitate a conversation about the audience for their project. We asked questions such as:

After careful consideration and deliberation, these young authors felt strongly that they wanted to write to younger members of the Bronx Business community — primarily incoming students and siblings — in an effort to offer meaningful advice. Over the course of the project, students at BHSB were able to hone and refine their writing, particularly as it relates to communicating with their chosen audience. They were able to revise their writing to include more colloquial language and tone, which they recognized would be most effective for communicating with their young and familiar audience. As a result, they published The Barriers We Faced, The Bridges We Built. This collection highlights the obstacles many BHSB students have encountered — moving to a new country, struggling in school, and disagreeing with family and friends. Though many of these obstacles seemed insurmountable, these young authors were able to meet them head-on with persistence and resilience, building the bridges necessary to overcome their personal barriers.

Encourage students to adjust their writing style based on their intended audience.

Do you change the style, tone, and format of your writing depending on who the writing is for? Of course you do. Do you teach your students to do the same?

Whatever your answer, it’s important for student writers to truly analyze, discuss, and contemplate their audience. Thinking about the audience they are writing for can inject a different form of energy into students and subsequently, their writing. In addition, getting students to adjust their language and writing style based on the audience they’re interacting with is a transferable, life-long skill that will benefit them down the road. I recently introduced a Student Press Initiative project in an 11-12th grade class at one of our long-time partner schools, the Bronx’s Morris Academy of Collaborative Studies (MACS). This class, which is labeled as a Peer Group Connection (PGC) class, consists of 25 junior and senior students that act as peer mentors for incoming freshmen. These 25 PGC students participate in weekly outreaches with freshmen to help support their transition to the academic and social challenges of high school. Peer mentors and mentees that participate in PGC express an increase in their academic achievements, developed social/relationship skills, and are more motivated to graduate high school. Given the impact of this program, the staff and students at MACS wanted every high school in the Bronx to include a peer-mentorship program in their curriculum, and decided the book we would create would promote the PGC program to other principals in the Bronx. And thus, we had our audience.

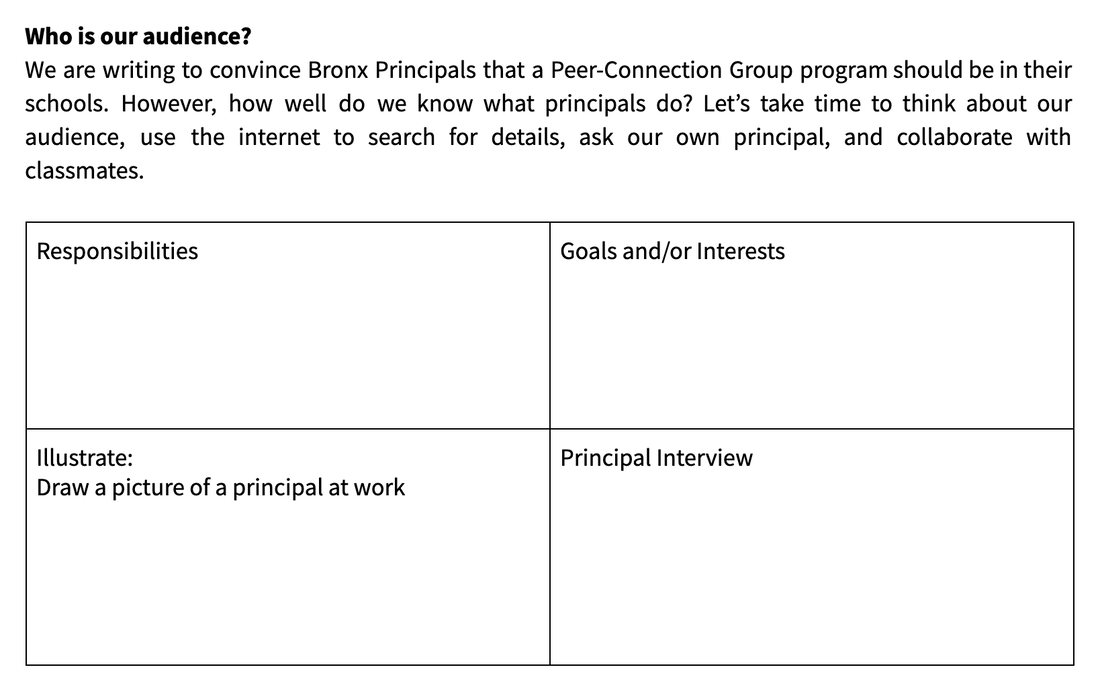

Who is our audience?

Throughout this project, the students’ writing has been powerful, raw, and passionate. At times, the energy in their writing was so strong that it was challenging to harness and refocus that energy to address our specific audience. To help students keep their audience in mind when writing, we used a few strategies. First, we (myself and the PGC teaching staff) organized the students into three writing groups: pathos, logos, and ethos. We created these writing groups to design an environment in which students could constantly engage with and think about their audience. In addition, these rhetorical devices helped influence students to produce persuasive writing from day one, which added another layer of excitement into the writing process. Second, I designed a graphic organizer called “Who is our Audience?” for students to reference. This tool allowed students to explore their audience (Bronx principals) in multiple ways — what are their interests, their responsibilities, their goals? This activity proved to be influential for students, as it tested their interview skills, allowed them to receive direct feedback from their intended audience, and become more informed writers.

Lastly, we designed a Feedback Rubric that we could use with students while revising their writing. This rubric provides a checklist that writers can reference at any point throughout the writing process, and requires evaluators to reference specific examples from the text. See below for an example of the rubric and how you might complete each section.

Feel free to adjust our graphic organizer and rubric to your own needs, or use them as a starting point for your own project! If you’re interested in seeing the product of our collaboration with the PGC group at MACS, check back on our new releases page — we’ll be releasing our publication with MACS on May 31st. I wouldn’t be surprised if the writing included in this publication convinces you to introduce a peer-mentorship program at your school!

|

|

The Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) at Teachers College, Columbia University is committed to making excellent and equitable education accessible worldwide. CPET unites theory and practice to promote transformational change. We design innovative projects, cultivate sustainable partnerships, and conduct research through direct and online services to youth and educators. Grounded in adult learning theories, our six core principles structure our customized approach and expand the capacities of educators around the world.

|

ABOUT US

525 West 120th Street, Box 182 New York, NY 10027 416 Zankel Ph: (212) 678-3161 [email protected] Our Team Career Opportunities |

RESOURCES

Professional Articles Ready-to-Use Resources Teaching Today Podcast Upcoming PD Opportunities |

COACHING SERVICES

Custom Coaching Global Learning Alliance Literacy Unbound New Teacher Network Student Press Initiative |