|

Offer your students an opportunity to solve real world problems, demonstrate critical thinking skills, and collaborate with their peers.

Problems. There’s no shortage of them these days — the pandemic has spurred countless challenges and intense despair; there are too many to list. Teaching during the pandemic has been a challenge in and of itself, as we are always looking for ways for students to be engaged with curricula and drive their learning, and that’s hard to do whether we’re teaching in person or remotely.

If you think back to your college or grad school days, you may recall the constructivist thinkers, such as Jean Piaget, who believed that students learn best when they construct their own learning. Problem- and project-based learning offers teachers an opportunity to do just that — instead of telling students the answers, you can create a learning environment in which students learn through discovery, thinking, tinkering, reflecting, and developing answers on their own. We may already be familiar with ways that we can bring this type of learning to in-person classrooms, but it can also be delivered to students who are learning in remote or blended environments.

Problem-based learning vs. project-based learning

Project-based learning is situated in real-life learning. The Buck Institute for Education defines project-based learning as a “teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an authentic, engaging, and complex question, problem or challenge.” If you ever walk into a classroom and see students working on a project with an exciting buzz in the room, chances are, their teachers have designed a project-based learning task. In our own lives, we know that when working on a project, we often discover a problem we didn’t realize we had — but once it surfaces, it demands a solution. (Remember those early pandemic days when we were acclimating to teaching remotely, but also trying to solve the problem of having no dedicated teaching space at home?) In teaching, this idea rings true, too. As we are learning more about a topic, we may discover a problem alongside our students, and this is the breeding ground for an exciting new project. This is the foundation of problem-based learning. Problem-based learning also offers students real-life learning opportunities, as well as the chance “to think creatively and bring their knowledge to bear in unique ways” (2020 Schunk, p. 64). Problem-based learning can look differently depending on the content and grade level, but often includes group discussions that allow for multiple perspectives on a topic, a simulated situation that involves role playing, or group work that includes both collaborative work and time to complete tasks individually. Problem-based learning promotes autonomous learning, self-assessment skills, planning time, project work, and oral and written expression skills. According to a July 2020 article from the Hechinger Report, problem-based learning has gained tremendous momentum, because it allows students to work more freely and at their own pace — a key advantage when learning remotely. In problem-based learning, the content and skills are organized around problems, rather than as a hierarchical list of topics. It’s also inherently learner-centered because the learner actively creates their own knowledge as they attempt to solve the problem.

Putting the “Problem” into Practice

As former English teachers, we both understand the challenge of putting new professional learning into practice. For teachers who need a refresher on how to design a problem-based learning experience for their students, Problem Based Learning: Six Steps to Design, Implement and Assess breaks down the steps to move PBL into practice as follows:

To help put these problem-based steps into perspective, we can look to our recent work with partners from a high school in the South Bronx. The chemistry team there decided to use an anti-racist lens while addressing a problem that was very real to their students — fireworks. During the summer of 2020, there was a record number of firework incidents in New York City. According to an article in the New York Times, the city received over 1,700 fireworks complaints in the first half of June alone. Our partners used this problem as an opportunity for students to research fireworks from multiple lenses, and imagine how they might present their findings and recommendations to local officials. After all, shouldn’t New York Governor Andrew Cuomo hear from high school students in the Bronx about the effects fireworks have on their communities? Here’s what the framework might look like in this example:

From here, we can imagine the possibilities for this framework, considering how students might address the underlying problem from different perspectives and content areas:

Teaching and learning throughout a global pandemic has presented more than its share of challenges. Out of necessity, tremendous innovation has taken place with the use of technology, pedagogy, and curriculum. With problem-based learning, we can continue this innovation in our classrooms, offering our students opportunities to solve real world problems, demonstrate critical thinking, and collaborate with their peers. We would love to hear what problem-based learning tasks you are designing for your classrooms!

Give students the chance to move — intellectually, physically and emotionally — into the world of a text.

We begin our session with an exercise borrowed from Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, Massachusetts. Players (our term for students and teachers who are in creative collaboration with each other) disperse throughout the room facing in any direction and are invited to move silently about the room at their own pace without collision, always passing through the center of the room en route to another side (rather than merely circling the periphery). Welcome to the act of milling and seething.

The purpose of this introductory activity is twofold: first, to foster an awareness of space. All too often in school, students are aware of neither the classroom as a physical space nor themselves and their peers as bodies coexisting within that space. Milling and seething prompts students to examine the entirety of the classroom space; at points, the facilitator leading the activity claps and says, “Look around. Are there any empty places in the room? When I clap again, move to fill them.” Students thus begin to notice the gaps and spaces within the room at any given time and to understand their responsibility to venture out and fill those gaps and spaces. And because of the mandate that they move through the center of the room as they mill and seethe, students must negotiate encounters with one another. They must become aware of where their individual bodies end and the bodies of others begin. Second, to ease players into imaginative work without any burden of “performance.” There exists no audience in this exercise; all are players. Players need only follow the directions of the facilitator (“When I clap, pause wherever you are. When I clap again, begin moving.”), and these directions shift subtly as the exercise progresses. While at first, the facilitator might ask players to “speed up (or slow down) by 50%, whatever that means to you,” directions ultimately become more like this one: “Pause. You have somewhere important to be. You’re late. When I clap again, get there.” Even with this simple direction, the players start to move into imaginative worlds.

Reimagining texts and teaching

The Literacy Unbound initiative, the driving force behind this session, was originally conceived as a grand experiment in teacher education that sought to encourage instructors to consider the power of artistic play as an opportunity to help students develop as critical, collaborative, creative readers. At its core, Literacy Unbound seeks to reinvigorate students and teachers through project-based, collaborative curricula developed around challenging texts. Throughout this process, we often witness increased student engagement and the development of a stronger classroom community. By bringing students and teachers together as creative collaborators, we’re able to reimagine the acts of reading, writing, listening, and speaking through multiple modalities. Though various aspects of this process can change, the core principles always remain the same:

Why does this work?

Through this approach, students get the chance to move — intellectually, physically and emotionally — into the world of the text. So frequently, we talk about text in the classroom. By contrast, our process allows students to talk from within the text; they speak directly from the perspective of one character and then another. They can feel the story in ways that might not otherwise be possible. At Literacy Unbound, we believe strongly that rich meaning-making happens when we find ways to experience literature together in the classroom.

Support students in establishing their voices as writers while advancing teacher leadership in reading and writing instruction.

Student writing is often read by one person (a teacher), and for one reason (a grade). But what if it could be different?

Through our Student Press Initiative, we seek to engage students in writing projects that culminate in print-based publications. These publications are designed for specific audiences, shaped around specific genres, and become widely accessible to their school community and the general public. This process not only helps students to establish their voices as writers, but helps revolutionize education by advancing teacher leadership in reading and writing instruction.

Raising the bar for student writing

Though each publication is a unique reflection of its student authors, the five phases of our publication process remain constant:

Publication in action: personal narratives from the Bronx

This spring, we supported 9th and 10th grade Special Education students at the Bronx High School for Business (BHSB) through this process. Their teacher was eager to introduce a project that would provide her students the opportunity to share a meaningful experience through the writing of a personal narrative or poem. With this in mind, our coaches worked alongside the teacher and her students to facilitate a conversation about the audience for their project. We asked questions such as:

After careful consideration and deliberation, these young authors felt strongly that they wanted to write to younger members of the Bronx Business community — primarily incoming students and siblings — in an effort to offer meaningful advice. Over the course of the project, students at BHSB were able to hone and refine their writing, particularly as it relates to communicating with their chosen audience. They were able to revise their writing to include more colloquial language and tone, which they recognized would be most effective for communicating with their young and familiar audience. As a result, they published The Barriers We Faced, The Bridges We Built. This collection highlights the obstacles many BHSB students have encountered — moving to a new country, struggling in school, and disagreeing with family and friends. Though many of these obstacles seemed insurmountable, these young authors were able to meet them head-on with persistence and resilience, building the bridges necessary to overcome their personal barriers.

Encourage students to adjust their writing style based on their intended audience.

Do you change the style, tone, and format of your writing depending on who the writing is for? Of course you do. Do you teach your students to do the same?

Whatever your answer, it’s important for student writers to truly analyze, discuss, and contemplate their audience. Thinking about the audience they are writing for can inject a different form of energy into students and subsequently, their writing. In addition, getting students to adjust their language and writing style based on the audience they’re interacting with is a transferable, life-long skill that will benefit them down the road. I recently introduced a Student Press Initiative project in an 11-12th grade class at one of our long-time partner schools, the Bronx’s Morris Academy of Collaborative Studies (MACS). This class, which is labeled as a Peer Group Connection (PGC) class, consists of 25 junior and senior students that act as peer mentors for incoming freshmen. These 25 PGC students participate in weekly outreaches with freshmen to help support their transition to the academic and social challenges of high school. Peer mentors and mentees that participate in PGC express an increase in their academic achievements, developed social/relationship skills, and are more motivated to graduate high school. Given the impact of this program, the staff and students at MACS wanted every high school in the Bronx to include a peer-mentorship program in their curriculum, and decided the book we would create would promote the PGC program to other principals in the Bronx. And thus, we had our audience.

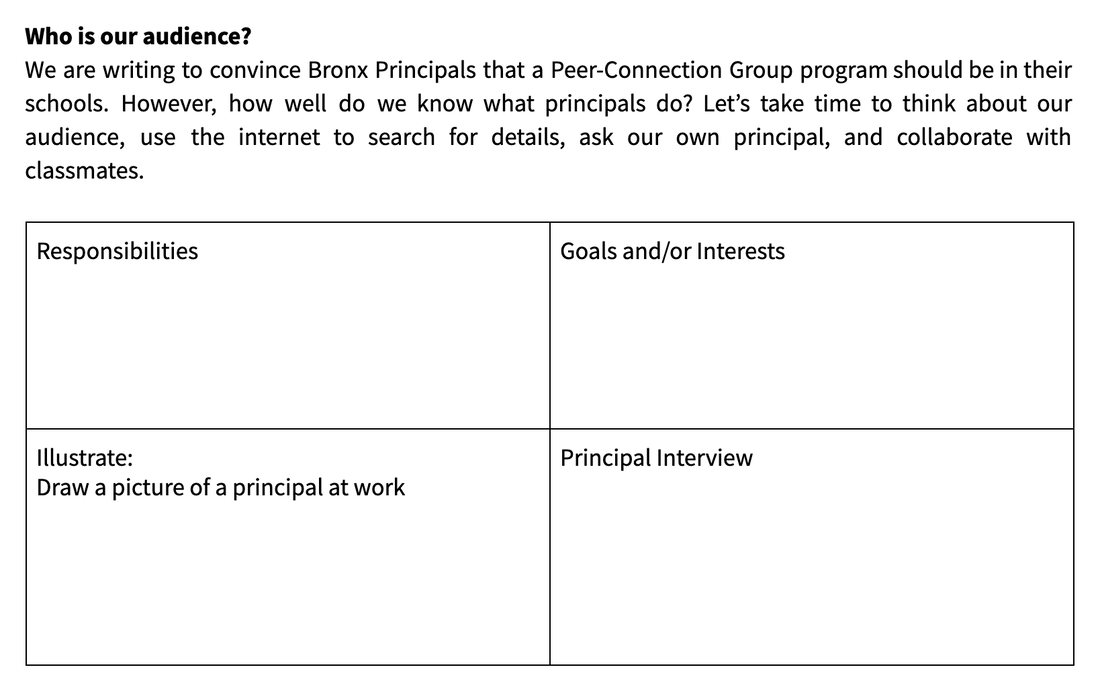

Who is our audience?

Throughout this project, the students’ writing has been powerful, raw, and passionate. At times, the energy in their writing was so strong that it was challenging to harness and refocus that energy to address our specific audience. To help students keep their audience in mind when writing, we used a few strategies. First, we (myself and the PGC teaching staff) organized the students into three writing groups: pathos, logos, and ethos. We created these writing groups to design an environment in which students could constantly engage with and think about their audience. In addition, these rhetorical devices helped influence students to produce persuasive writing from day one, which added another layer of excitement into the writing process. Second, I designed a graphic organizer called “Who is our Audience?” for students to reference. This tool allowed students to explore their audience (Bronx principals) in multiple ways — what are their interests, their responsibilities, their goals? This activity proved to be influential for students, as it tested their interview skills, allowed them to receive direct feedback from their intended audience, and become more informed writers.

Lastly, we designed a Feedback Rubric that we could use with students while revising their writing. This rubric provides a checklist that writers can reference at any point throughout the writing process, and requires evaluators to reference specific examples from the text. See below for an example of the rubric and how you might complete each section.

Feel free to adjust our graphic organizer and rubric to your own needs, or use them as a starting point for your own project! If you’re interested in seeing the product of our collaboration with the PGC group at MACS, check back on our new releases page — we’ll be releasing our publication with MACS on May 31st. I wouldn’t be surprised if the writing included in this publication convinces you to introduce a peer-mentorship program at your school!

Project-based learning through stop motion.

Each year at our Big Learning Challenge institute, we harness the power of 21st century capacities and offer educators the opportunity to navigate the project-based learning process as participants, as well as teachers looking to implement new instructional strategies in their classrooms.

At our last institute, we explored the theme of seeds, and set out to address the question: what happens when you plant a seed? In a unique stop motion workshop, we allowed teachers to determine how to represent their response (literally, or with an abstract interpretation?), decide on a story line (which scenes would they include?), and create their props using clay and paper. It wasn't child’s play, though — they were on a mission to create a stop motion film by the end of our session. Stop motion is a film making technique which uses a sequence of still images to create the illusion of movement. When the individual images are combined, slight movements in the figures that are photographed create “motion” in the film. This technique was fitting for our project-based learning (PBL) focus at the Big Learning Challenge, since PBL is a dynamic approach that allows for collaboration, problem-solving, and creativity.

Using technology to tell stories

Each team of teachers would need to determine how to represent their response (literally, or with an abstract interpretation?), decide on a story line (which scenes would they include?), and create their props using clay and paper. Before we started, I could sense that some teachers were nervous about tackling this project a short amount of time. It was a new concept for some, and required a bit of software to accomplish. We used the Stop Motion Studio app, which is free and easy to use. The app allows you to capture photos using your phone, adjust your frames per second (FPS), and easily export your finished product as a movie file. From there, it’s simple to share your work on various platforms. Once we’d covered the tools we could use, we were ready to begin the film making process. As each group moved on to making their films, they were deeply engaged in their work. To make a short film, they had to create about 6-10 photos for each second of the film. For a one minute film, that means creating 100-150 photos! This detailed work was achieved through a diligent process of creating scenes, moving props, taking pictures, and moving props again, over and over until reaching the desired result. When their films were finished, we discovered that both teams created two very different stories: one team created a more scientific story about plant growth, while the other took on a social studies perspective, exploring how individuals cultivate values.

What would this project look like in your classroom?

But that was not the end of it. Sure, we had fun making these clips (the outcomes were amazing!), but our larger purpose was to explore how teachers could bring this activity back to their classrooms. Throughout the process of creating a short film, teachers were tasked with being creative, organized problem-solvers. They faced challenges when working with props, developing storylines, and had to exercise patience while learning a new technique. By experiencing these elements for themselves, they were better equipped to anticipate the benefits and challenges of implementing a similar project with their students. Each teacher set out to imagine how this project could be replicated with their students. They explored ideas like using stop motion to examine narrative structures in ELA classrooms, help ELLs learn adverbs of sequence, and to create an interdisciplinary project for a technology and media class. How might you implement a stop motion project in your classroom? Check out these ideas to help you get started:

We hope you try a stop motion project in your classroom!

One school's journey with assessing and designing proects rooted in authenticity.

In a diverse learning environment, where all students are, to some degree, ENL and many of them are SIFE, designing instruction that not only meets all students where they are in their journeys through school but also invites them to work towards mastery of college- and career-ready skills can be quite daunting.

Claremont International High School in the Bronx serves students who are recent immigrants to the United States from countries ranging from the Dominican Republic to Gambia to Yemen. For Claremont, the pedagogical approach that best addresses this challenge is project-based learning (PBL), and the faculty there invest a great deal of energy in designing projects that are authentic.

Assessing authenticity

John Larmer of the Buck Institute of Education, a clearinghouse for teacher professional learning about PBL, sets out a four-point framework for assessing the authenticity of a project, which he claims can be measured along a “sliding scale.” Let’s use Larmer’s four claims as a lens through which we can examine and evaluate a project planned by the 12th-grade Government teacher at Claremont, who has the responsibility and privilege of guiding a cohort of new- and soon-to-be Americans through their first deep exploration of the U.S. Constitution and the political process that has sprung up around it. 1. “It focuses on a problem, issue, or topic that is relevant to students’ lives [or] is actually being faced by adults in the world students will soon enter.” Claremont's Government project asks students to choose a controversial topic that is actively being debated in the American political discourse, independently research the history of the issue and its current state of play, and construct an understanding of the complexities of the problem. Students often select topics such as gun control, reproductive rights, and income inequality. By offering students an opportunity to exercise their agency in selecting their research questions, the teacher works toward ensuring the relevance of the inquiry to his students, and by grounding the work in contemporary issues, he points students toward developing “real-world” knowledge. 2. “It sets up a scenario or simulation that is realistic, even if it is fictitious.” This project asks students to imagine themselves as participants in the legislative and judicial processes, not as elected or appointed officials, but as activist citizens or residents of the United States. This orientation requires students to play roles that are immediately accessible them, not only after they graduate but also in that very moment as high school seniors. 3. “It meets a real need in the world beyond the class, or the products students create are used by real people.” Because the debates into which this project invites students are unsettled in the ongoing political discourse, the work students produce constitute contributions to these national conversations about the direction of the country. All of the students will “go public” with their learning (an essential feature of PBL) in the form of oral defenses of their written work, but they may also elect to actually publish the documents they write or send them to government officials. Thus, students are positioned to engage with democratic processes, not just study them. 4. “It involves tools, tasks, or processes used by adults in real settings, and by professionals in the workplace.” Students’ final products generally fall into one of two genres of writing used by professionals working in government. Those students who choose to engage with a debate that is active in the legislative process write white papers, research-driven reports that recommend policy. Those who enter conversations around active court cases write amicus curiae briefs, documents that seek to influence the decisions of a court. Far from the standard school-centric argumentative essay, white papers and amicus curiae briefs are examples of real-world writing and authentic tools used by professionals.

The 12th-grade Government project at Claremont is probably best described as “somewhat authentic” according to John Larmer’s framework. The work that students are doing, both in the roles they play and the products they create, “simulates what happens in the world outside the school.” However, it would not take too much effort for the project to become “fully authentic” if students “take action to improve their community” by publishing or submitting their white papers and amicus curiae briefs to the appropriate government authorities. Either way, the authentic project designed by this teacher offers students the opportunity for authentic learning.

|

|

The Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) at Teachers College, Columbia University is committed to making excellent and equitable education accessible worldwide. CPET unites theory and practice to promote transformational change. We design innovative projects, cultivate sustainable partnerships, and conduct research through direct and online services to youth and educators. Grounded in adult learning theories, our six core principles structure our customized approach and expand the capacities of educators around the world.

|

ABOUT US

525 West 120th Street, Box 182 New York, NY 10027 416 Zankel Ph: (212) 678-3161 [email protected] Our Team Career Opportunities |

RESOURCES

Professional Articles Ready-to-Use Resources Teaching Today Podcast Upcoming PD Opportunities |

COACHING SERVICES

Custom Coaching Global Learning Alliance Literacy Unbound New Teacher Network Student Press Initiative |