|

Simple shifts that help introduce racial literacy skills in developmentally appropriate ways.

It was a Friday evening, and my kiddo and I were putting her books back on the shelf after some reading time. The ideas that were swirling in my head all week about narrative inquiry and professional development had finally started to settle. Leave it to a preschooler to stir the pot.

“Mom, why didn’t MaVynee and her family get to go to those other beaches?” You see, we had just finished Saving American Beach: The Biography of African American Environmentalist MaVynee Betsch by Heidi Tyline King and illustrated by Ekua Holmes. In this beautiful picture book, King and Holmes tell MaVynee’s story through her connection to American Beach, a place her grandfather bought during the Jim Crow era when Black people were barred from other beaches due to racist policies and the racist politicians who made them. Although we've discussed segregation before, as my daughter has gotten older, she has asked more and more questions. It was clear that she was having trouble understanding segregation, as it goes against our deepest family values of inclusion and love. She was starting to see outside our family, and I knew these were conversations in need of great care and thought. In the coming months, I would love to share some of my wonderings and conversations with you. We’ll start off with conversations sparked by Black History Month, but of course, I encourage you to celebrate Black history all year round, as Black history is our history. We begin this journey together at the library, working through a stack of books suggested by librarians and websites. Below you’ll find a few guiding suggestions that allow you to introduce racial literacy skills in developmentally appropriate ways for preschoolers.

Be aware of the language you're using

The language we use and have available to us allows us to interpret the world, and for this reason, I am always curious about the ways authors choose to tell stories. In a few of the picture books we encountered about enslavement, the Civil Rights Movement, and remarkable people in Black history, I noticed there were some terms I wanted to switch. For example, I changed the term “slave” to “enslaved” when we came across it in a text about Harriet Tubman. Changing the term “slave” to “enslaved” preserves the humanity of those who were enslaved; when we use the term “slave,” we are making it sound like a pre-existing condition, while when we use the term “enslaved,” it can spark important conversations about power and racism. Another example is when one text stated that Black students could not attend school with white students because they were Black. This is incorrect. We want to be sure that we are not using language structure that puts the blame on the color of someone’s skin; Black people were not allowed to do many things not because of the color of their skin, but because white people in power were racist and created racist rules. I was able to switch these terms out and rearrange language because my kiddo cannot read yet, but if you have kiddo(s) and/or students who can read, take the opportunity to talk to them about why we’re critically thinking about the language used, something important to highlight when developing racial literacy skills.

Introduce new concepts, like segregation, through familiar vocabulary and visualizations

Although my kiddo and I have read books centering Black history since she was born, she really wanted a concrete understanding of the term “segregation” as evidenced by her continuous questions. We began first by discussing different skin colors, bringing up an episode of a TV show where they mixed paint for different people in the neighborhood and re-reading a picture book that explains melanin. She felt satisfied with that, and so we discussed how that is connected to “segregation” using their diverse set of dolls.

First, we discussed all the different skin colors in her doll collection, and then I separated the dolls with darker skin tones from white dolls. Some of the books we were reading discussed racial segregation in schools, so at this point, I took a young Black doll and a young white doll and moved them across our train rug to show that they would have to attend different schools if they were segregated. When my kiddo asked why, I was sure not to say, “Because they were Black,” but rather, “There were some white people in power who thought that they were better than people with darker skin. That’s called racism. They did not want to have their kids go to school with people who had darker skin, and so they segregated the schools. Because they were powerful people, they were able to make up these rules.” I asked my kiddo if she thought this was “fair,” a term I know she has access to, and we had a conversation about why it’s not fair. My child also attends a diverse school, and she was able to bring this learning to her experience and note that she would never want her friends to have to go to another school. When she asked why people followed these rules, I read her books that centered Black Joy and resistance.

Celebrate Black Joy and resistance!

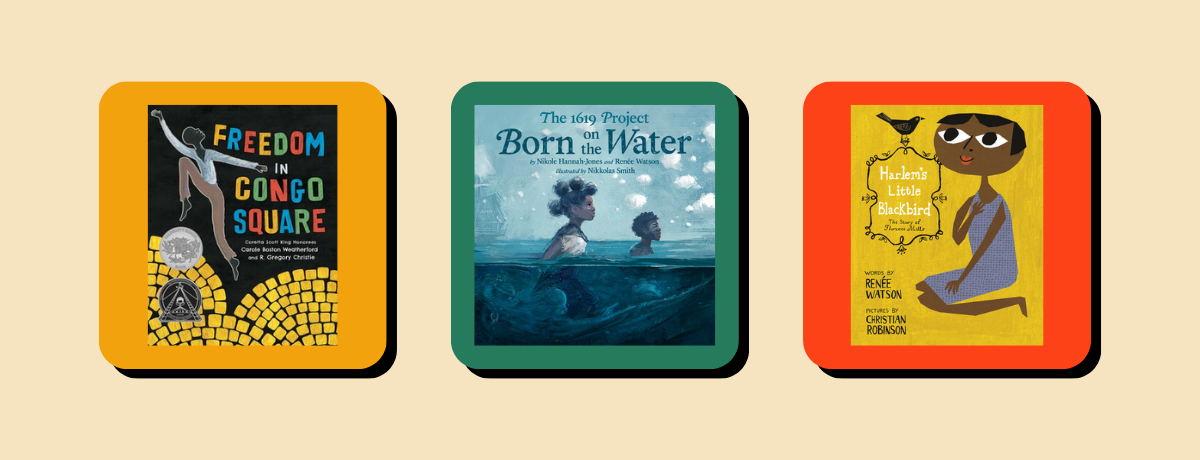

Have you ever heard of Congo Square in New Orleans? How about Hush Harbors? Or maybe you learned about the ways enslaved people would map out escape routes in their hairstyles? I did not know any of this until after I graduated with a Master’s degree — a fact that I am a bit ashamed of — but I never stopped learning. As a parent, it was important for me to reflect on what I learned, how the stories silenced harmed my racial literacy development as a white-assumed person, and think through ways I can share my learning with my kiddo. My K-16 schooling experience included the devastating effects of enslavement (rightfully so), but I never learned about the ways Black people resisted and continued to fight for their humanity in the face of violence. As I watch my child grow, I know that foregrounding how oppressed people fought their oppression and oppressors and found joy is imperative in her racial literacy development. Here are some titles that my daughter and I have read:

This is just the beginning, but there is something remarkable about that. There were many things I was not taught, and there were things that my teachers hyper focused on that told a story very different from the stories I know now. I am grateful for my learning, mostly due to the work of Black women and trans scholars, and I look forward to developing my daughter’s racial literacy much earlier than mine.

As my daughter and I work through these stories, we’ve begun discussing the ways racism and segregation are still a part of life in America, but that is an article for another day. I hope that sharing my thoughts, considerations, and conversations with you can help spark some story shifting and new learning for you and yours. |

|

The Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) at Teachers College, Columbia University is committed to making excellent and equitable education accessible worldwide. CPET unites theory and practice to promote transformational change. We design innovative projects, cultivate sustainable partnerships, and conduct research through direct and online services to youth and educators. Grounded in adult learning theories, our six core principles structure our customized approach and expand the capacities of educators around the world.

|

ABOUT US

525 West 120th Street, Box 182 New York, NY 10027 416 Zankel Ph: (212) 678-3161 [email protected] Our Team Career Opportunities |

RESOURCES

Professional Articles Ready-to-Use Resources Teaching Today Podcast Upcoming PD Opportunities |

COACHING SERVICES

Custom Coaching Global Learning Alliance Literacy Unbound New Teacher Network Student Press Initiative |