|

Students' cultures, like trees, are living entities. Are you providing rich soil to help them grow?

CRSE, or Culturally Responsive and Sustaining Education, has become a focal point for many districts across the nation, including the New York Department of Education. In the NYC DOE’s Mission and Vision statement, they explain why CRSE is so important and how educators can ensure their units, lessons, and activities are culturally sustaining.

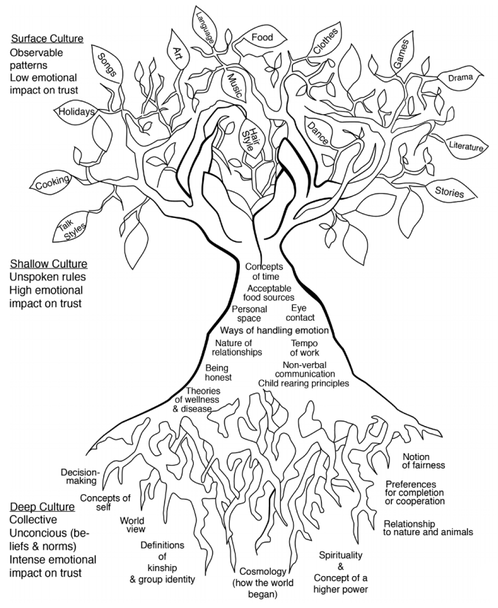

But how do we define culture, and do we know our own cultures well enough to help our students discuss theirs? Most educators are familiar with Hall’s “cultural iceberg” model, which uses the physical makeup of an iceberg as a metaphor for culture; 10% of an iceberg is seen above water, while the other 90% is below the surface. This encourages educators to recognize that what they see is only a small fraction of culture, and to be truly culturally responsive and sustaining, educators have to be aware that 90% of culture is invisible. Part of this learning process is to make the unseen seen, which is where Zaretta Hammond’s cultural tree comes in. (We also dive deeper into Zaretta Hammond’s work in our Touchstone Texts for Equity course, which uses her Culturally Responsive Teaching & the Brain as a seminal text for creating more equitable classrooms.)

Source: Zaretta Hammond, Culturally Responsive Teaching & the Brain

Hammond’s “cultural tree” identifies three levels of culture:

A fellow English educator, Dante Brito Jr., uses the image of a tree to help his students visualize their own levels of culture, prompting them to consider their leaves, what constitutes their trunk, and how their roots keep them grounded.

Examining my own tree

In my student experience, teachers would always ask me about my culture, but then never share about theirs. Just as it’s important to get to know our students, they need to get to know us. But do we know ourselves? What would our trees look like? On the surface level, my leaves are quite unassuming. I am currently wearing jeans with comfortable sneakers, and my shirt says “Don’t Erase History” with books, one I bought this past summer at the Human Rights Campaign store. As far as the eye can see, I am a white woman, probably an educator, and most likely work for equity and social justice. There are many things my “leaves” communicate to people, some of which are correct and some not so. My deep culture is complicated. First, I may be white assumed, but I identify as multiracial; my roots are a combination coming from different trees, making a web of sometimes contradictory beliefs and norms. I grew up in America in a racially segregated town, and so much of what I learned growing up was based on Eurocentric values and the myth of meritocracy. On the other hand, my grandmother was a Japanese American woman who moved here shortly after World War II to wed my grandfather, a Baptist from rural North Carolina. Traveling to new places is in my blood, and although my grandmother thought assimilating in public was the best route for herself and her three boys, she never lost sight of who she was behind closed doors. What does this mean for me? Sometimes I feel as if I am a twin tree, two trunks reaching for the sun but connected to the same roots. When I shared this experience with my students, I’ve never had a year where at least one didn’t say, Me too.

Providing rich soil for students

I found it fascinating to create my cultural tree, but what does this mean for our classrooms? Our students have their own trees, and we can provide soil to help them grow. I realized this when I questioned how my tree has changed over time. As someone dedicated to learning, my culture shifts as I critique the foundations of my home culture while adopting new practices and epistemologies. I guess you could say I’ve been changing the soil, potting myself in different environments with new people, new cultures, and new roots. What kind of soil do you provide for your students? How do you make that soil rich with nutrients to support their trees? Unfortunately, the soil in this country tends to offer stereotypes of cultures, essentializing people until all that’s left is Taco Tuesday and Bollywood. How does your classroom challenge these stereotypes, and how can you provide environments where students are able to dig up their beliefs, hold them to the light, and decide whether or not those norms and beliefs benefit them and their communities? The cultural tree visual is just one way to get to know your students and yourself. Below, there are a few other activities that educators have shared with me:

— Mikhail Epstein, “Postcommunist Postmodernism: An Interview”

This work is not easy. It requires educators and their students to examine their thinking, behavior, and make the unconscious conscious. Culture is usually seen as something static, and I think it’s important to consider ways in which culture might change. Our students can create healthy trees if we provide the right soil.

Cultural trees are also a part of larger forests. Leaves change as students interact with their classmates, their teachers, and other community members. The relationships you build with them in addition to the relationships they build with themselves will constantly inform their culture, as trees, like culture, are living entities. |

|

The Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) at Teachers College, Columbia University is committed to making excellent and equitable education accessible worldwide. CPET unites theory and practice to promote transformational change. We design innovative projects, cultivate sustainable partnerships, and conduct research through direct and online services to youth and educators. Grounded in adult learning theories, our six core principles structure our customized approach and expand the capacities of educators around the world.

|

ABOUT US

525 West 120th Street, Box 182 New York, NY 10027 416 Zankel Ph: (212) 678-3161 [email protected] Our Team Career Opportunities |

RESOURCES

Professional Articles Ready-to-Use Resources Teaching Today Podcast Upcoming PD Opportunities |

COACHING SERVICES

Custom Coaching Global Learning Alliance Literacy Unbound New Teacher Network Student Press Initiative |