|

Creativity flourishes in an environment where exploration is encouraged and individual voices are celebrated.

Genre-based writing is the art of crafting narratives within distinct literary genres or categories. Literary genres, such as fiction, non-fiction, poetry, drama, science fiction, fantasy, mystery, and romance, are defined by specific stylistic elements, forms, and content.

Engaging in genre-based writing involves intentionally aligning one's writing with the conventions, themes, and structures associated with a chosen genre. This process includes utilizing storytelling techniques, incorporating stylistic elements, and exploring themes relevant to the selected genre. For instance, a mystery novel might feature a central crime, a detective, and a resolution, while a romance novel centers around a key romantic relationship within the plot.

Why genre-based writing matters: a deeper exploration

Recognizing the significance of genre-based writing goes beyond the conventional understanding of major genres such as narrative, argumentative, and informative. It involves delving into the unique sub-genres, including speculative memoirs, flash fiction, Ted Talks, infographics, Op-Eds, and more. This exploration involves immersing oneself in an inquiry-based study of specific texts, a process that reveals nuances that often transcend traditional genre boundaries. Within this exploration, the promotion of creativity takes center stage. By encouraging students to engage with diverse sub-genres, teachers foster an environment where creativity can flourish. This approach not only sets clear expectations for writers, but also enhances their ability to communicate effectively with their audience. In doing so, it allows readers the freedom to choose works that are tailored to their preferences, fostering a deeper connection and appreciation for the art of writing. The Student Press Initiative (SPI), a signature initiative at CPET, strongly advocates for genre-based writing as a meaningful framework that not only expands literary possibilities, but also nurtures the creative spirit within each student.

What does genre-based writing entail?

SPI serves as a guiding force for both teachers and students in the realm of genre studies, employing a close examination of exemplars — often drawn from a diverse array of published texts, ranging from poems and essays to PSAs. In this process, students engage in a detailed analysis of these texts, examining content, structure, and craft through the lens of a writer, taking in all of its attributes and conventions in the process. The collaborative nature of this exploration lays the groundwork for creativity. Through shared discussions and the creation of charts, students collectively share insights into the genre and its unique characteristics. Rather than prescribing what or how to write, teachers adopt an empowering stance, encouraging students to explore and discover, thereby nurturing the development of insightful ideas and observations. This student-driven approach not only empowers individuals but also transforms the teacher's role from knower, to that of a facilitator or provocateur, cultivating a powerful space for exploration, self-discovery, and creativity. In a recent workshop I facilitated, SPI coaches immersed themselves in a genre-based study of the poem "What For" by Garret Hongo. While I’ve used this poem many times on many different occasions, I’m always impressed by the new ideas, observations, and questions that arise, underscoring how readers engage uniquely with texts. Collective discussions delved into content, form, and structure, highlighting original stylistic moves by the author. For instance, one coach noted changes in stanza lengths, sparking a discussion on its intentional contribution to the poem's meaning. Another coach made note of his powerful auditory imagery, and another made content connections to the American Dream. This exploration set the stage for coaches to embark on their own creative journeys, crafting "What For" poems inspired by Hongo's content, form, and craft, including elements such as repetition and reiterated structures. Reflecting on the similarities and differences among these poems further deepened the collective understanding of this specific genre, demonstrating how creativity flourishes in an environment where exploration is encouraged and individual voices are celebrated.

Unleashing creativity and self-discovery

In summary, genre-based writing is a powerful tool for creativity, independent thinking, and self-discovery. Embracing this approach turns educators and students into skilled explorers of various literary genres, creating a collaborative and empowering learning space.

Support emerging readers' vocabulary with a balance of explicit instruction and in-context learning.

This is the fifth installment in our Science of Reading series

Vocabulary is a crucial component of reading comprehension and literacy development. Understanding vocabulary and its significance is essential for educators as they work to support emerging readers on their journey to becoming skilled and proficient readers. In this fifth and final installment focused on the science of reading, we will unpack what vocabulary means, why it is important, and provide three promising practices that teachers can implement to effectively support emerging readers with vocabulary development.

What is vocabulary in the science of reading?

In the science of reading, vocabulary refers to the collection of words that a reader understands, recognizes, and can use effectively in their reading and writing. It encompasses both oral vocabulary (words we understand and use in speaking) and print vocabulary (words we recognize and understand in reading). Vocabulary development is a multifaceted process that involves word learning, comprehension, and retention.

Why is vocabulary development important?

Vocabulary serves as the anchor connecting various critical reading skills, fostering a deeper understanding of phonological awareness, phonics, and fluency. In phonological awareness, it enhances recognition and discernment of sounds within words, ultimately aiding in the decoding and pronunciation processes. When it comes to phonics, a robust vocabulary equips learners with the ability to detect word structures and pronunciation nuances, enabling them to effectively apply phonics rules during reading. Additionally, vocabulary ensures swift and accurate word recognition, which significantly contributes to reading speed and fluency. But perhaps most importantly, vocabulary enhances reading comprehension by giving readers the capability not only to recognize words, but also to understand their meanings within a text. Without a strong vocabulary, readers will likely encounter difficulties in grasping the core of what they are reading, ultimately hindering overall comprehension.

Promising practices for vocabulary development

Plenty of vocabulary strategies exist, but issues arise when one approach is excessively emphasized or prioritized, potentially leading to minimal or even neglected use of others. For example, overreliance on explicit vocabulary instruction may lead to isolated word memorization without a deeper understanding of word usage in context. An effective approach strikes a balance between explicit instruction and in-context learning. Below, I present three promising practices, as well as concrete examples of how I implemented these practices in my classroom. I believe these examples encompass various methods for explicitly supporting young readers' vocabulary development. Ideally, teachers will utilize all three practices, at different times, to create a comprehensive and holistic approach to vocabulary instruction.

Vocabulary development is a fundamental aspect of reading and literacy. In the science of reading, understanding what vocabulary is and why it's important is crucial for educators. By implementing explicit vocabulary instruction, contextual learning, and engaging word play and games, teachers can provide effective support for emerging readers, helping them build a strong foundation for successful, lifelong reading.

Incorporate active comprehension strategies that allow students to deeply engage with the texts they encounter.

This is the fourth installment in our Science of Reading series

Throughout our science of reading series, we've been exploring the crucial aspects of reading proficiency. In this installment, we will delve into reading comprehension, a fundamental skill that transcends the mere decoding of words on a page. Comprehension involves understanding, interpreting, and making meaning from the text. This ability is essential for success because it enables readers to connect prior knowledge with new information, make inferences, identify main ideas, and draw conclusions.

In the context of the science of reading, which emphasizes evidence-based reading instruction, reading comprehension holds a critical position. It recognizes that reading is not a single skill, but rather a complex interplay of various cognitive processes. Furthermore, it acknowledges that reading comprehension is built upon a solid foundation of phonological awareness, phonics, and fluency, as discussed in our previous articles. These foundational skills are essential for developing proficient readers, as they provide the necessary groundwork for understanding the content of the text. Now, let's delve into the significance of incorporating comprehension strategies alongside fluency and phonics, highlighting how they enhance the reading experience for students.

The power of active reading comprehension strategies

While fluency and phonics lay the foundation for reading proficiency, active comprehension strategies are the key to unlocking the true potential of these foundational skills. Fostering deeper understanding: Comprehension strategies encourage students to dive deeper into the text. When they actively make predictions, ask questions, visualize scenes, or summarize key points, they engage with the material at a greater level. This not only aids in grasping the surface level content, but also enables them to explore underlying themes, character motivations, and the author's intent. Bridging gaps in proficiency: Active comprehension strategies bridge the gap between students who excel in fluency and decoding, and those who struggle. For those proficient in these areas, comprehension strategies provide the tools to dig deeper and extract more meaning from texts. Meanwhile, students who may struggle with decoding and fluency can still make powerful inferences and predictions when they engage with comprehension strategies. This inclusivity ensures that no student is left behind in their reading journey. Promoting critical thinking: Comprehension strategies encourage students to analyze information, draw connections, and evaluate the significance of details within a text. This not only enhances their comprehension, but also equips them with valuable life skills that extend beyond the classroom. Building lifelong readers: The integration of comprehension strategies nurtures a love for reading. When students actively engage with texts, they become more invested in the reading experience. This can lead to a lifelong passion for reading and learning, setting the stage for continued growth and success.

Effective strategies for promoting comprehension

Incorporating comprehension strategies alongside fluency and phonics is essential for developing well-rounded readers. Below are three strategies I found to be particularly helpful for supporting comprehension in my young readers.

Explicit comprehension instruction

One way to promote comprehension is to provide explicit instruction of evidence-based strategies, such as making predictions, asking questions, visualizing, summarizing, and making connections while reading. Encourage readers to actively engage with the text by discussing their thoughts and insights. Model these strategies and provide ample opportunities for guided practice. By equipping students with these tools, you empower them to extract deeper meaning from the text. When I was in the classroom, I leaned on pre-, during-, and post-reading strategies and exercises that were focused on the asking of questions. By teaching my students to ask questions about the story, I helped them become active readers who think deeply about what they're reading and develop a better understanding of the text. An example lesson might look like:

Vocabulary development

A robust vocabulary is crucial for comprehension, as it bridges decoding skills like phonics and the ability to understand and enjoy texts fully. When students encounter unfamiliar words while reading, a well-developed vocabulary allows them to unlock the meanings of these words, making the reading experience more enjoyable and meaningful.

By integrating vocabulary instruction into reading lessons with a focus on context clues, students not only enhance their comprehension skills, but also strengthen their phonics abilities by recognizing and deciphering unfamiliar words within the context of the text. This holistic approach ensures that students not only decode words accurately, but also understand them in the broader context of the story. Building a strong vocabulary enhances comprehension by enabling students to grasp the nuances and subtleties of language.

Independent reading

In my classroom, I embraced the power of independent reading as a key component of our literacy program. Independent reading, also known as "personalized reading time," was a daily activity where my students had the freedom to choose books or materials that both matched their reading levels and piqued their interests. Studies have found that when students are allowed to choose their own reading materials, they are more engaged and invested in the reading process, resulting in improved comprehension (Guthrie and Humenick (2004)). To support independent reading, I ensured our classroom library was stocked with a wide range of books and magazines. This diversity catered to different reading levels, genres, and topics, giving each student ample choices. During independent reading time, students had the autonomy to select their reading materials, which fostered a sense of ownership over their reading experience, making it more engaging and enjoyable. I worked closely with each student, mostly through conferencing, to ensure they selected books that matched their reading levels. This ensured that the material was neither too easy nor too challenging, promoting comprehension and confidence. To enhance comprehension and encourage reflection, I periodically organized book discussions or "book talks." If multiple students were reading the same book, we would gather for a group discussion. In these sessions, students had the opportunity to share their thoughts, insights, and favorite parts of the book. It promoted a sense of community and enthusiasm for reading. After each independent reading session, I encouraged students to reflect on what they had read and set personal reading goals. This reflection helped them track their progress and set targets for improvement. Lastly, students kept reading journals where they recorded the titles of the books they read, brief summaries, and personal reflections. These journals served as a valuable tool for tracking their reading journey. By incorporating independent reading into our daily routine, my students not only improved their reading comprehension, but also developed a genuine love for reading. It was a practice that empowered them to explore diverse texts, share their reading experiences, and become lifelong readers.

Elevating comprehension

By integrating explicit comprehension instruction, vocabulary development, and independent reading, educators can establish a holistic approach to literacy that extends beyond fluency and phonics. This approach ensures that students not only read accurately, but also engage deeply with, analyze, and appreciate the texts they encounter, equipping them with the full range of skills essential for reading development and proficiency.

Nurture confident readers by blending phonics into the fabric of your literacy instruction.

This is the third installment in our Science of Reading series

When it comes to early reading instruction, few topics have sparked as much debate and controversy as the teaching of phonics. Over the years, the pendulum has swung between extremes: some advocate for phonics as the exclusive focus of instruction, while others argue for its complete exclusion from the curriculum. However, the crux of effective literacy education lies in finding a harmonious balance. As part of my series dedicated to unraveling the science of reading and nurturing young readers, we embark on a journey into the world of phonics. What exactly is phonics, what role does it play in reading development, and how can early childhood educators incorporate it into their classrooms through a balanced approach?

Defining Phonics: The Foundation of Reading

At its core, phonics is the relationship between the sounds of spoken language and the letters that represent those sounds in written language. It's the code that unlocks reading comprehension. Phonics instruction involves teaching students how to connect the sounds of spoken language (phonemes) to the symbols (letters or letter combinations) that represent them (graphemes). We dig deeper into this topic in my previous article, which examines how to nurture phonological awareness in emerging readers. Phonics equips young readers with the skills needed to decode words — without phonics, the process of learning to read would be like trying to solve a complex puzzle without understanding the individual pieces.

The Purpose and Importance of Phonics

Phonics serves several crucial purposes in the development of young readers: Decoding Words: Phonics provides the key to unlocking unfamiliar words in texts. When students understand the relationships between sounds and letters, they can sound out words they haven't encountered before. Building Fluency: Proficiency in phonics helps build reading fluency. Fluent readers can read with accuracy, speed, and expression, which enhances comprehension, as we have discussed in previous articles. Spelling Proficiency: Phonics instruction also contributes to spelling skills. When students know the sounds associated with letters and letter combinations, they can spell words more accurately.

Balancing Act: The Key to Phonics Success

A balanced approach to phonics instruction is essential in literacy education for several reasons. Firstly, it facilitates a well-rounded development of essential reading and writing skills, encompassing phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, and writing proficiency. This holistic perspective acknowledges and embraces the diversity of learners, accommodating various learning styles and individual needs. The integration of phonics within authentic reading and writing contexts is a critical aspect of this approach. By immersing students in real-world applications of phonics skills, it not only reinforces learning, but also enhances reading fluency. This equips students with a range of word recognition strategies, lessening their reliance solely on phonics, and thereby improving reading efficiency. Furthermore, a balanced approach recognizes that the ultimate goal of reading is comprehension. It weaves phonics instruction together with comprehension strategies, ensuring that students not only decode words, but also understand and interpret the text they read. Creating a balanced approach to instruction can offer essential support for struggling readers, tailoring instruction to meet their specific needs and providing a scaffold for their literacy development. Ultimately, it fosters a deep appreciation for literacy, nurturing lifelong reading and writing habits, and in doing so, it aligns with evidence-based practices in literacy education.

A Balanced Approach In Action

As a third-grade teacher, I often recognized the need to teach phonics to specific groups of students, even though it wasn't a part of the standard curriculum. One approach I used was phonics through literature, where I selected books featuring specific phonics patterns, and integrated phonics instruction within shared reading sessions. For example, if I wanted to focus on the long a sound spelled with the silent e pattern (e.g., "cake," "gate”), I could use a book like Jake Bakes Cakes, which prominently features words with this pattern. I would then use this text to engage in a shared reading session, where I read the book aloud to the class, pausing at words with the target phonics pattern. For instance, when we encountered the word cake, I might emphasize the long a sound and point out the silent e at the end of the word. After reading, I would engage the students in a discussion about the phonics pattern, asking questions like, "What sound does the e make at the end of the word cake?" or "Can you find other words in the story with the same pattern?" To support word recognition, I would encourage students to identify and read words with the target pattern in the book. They might take turns reading sentences or identifying words on specific pages. I would also have students use magnetic letters or word cards to demonstrate how changing the vowel sound (e.g. cake to make) affects the word's pronunciation and meaning. Students would then manipulate letters to create new words following the same pattern. If there was time, I would also ask students to engage in word play activities related to the phonics pattern, such as creating rhyming words or making word family charts, to reinforce the concept. As a follow-up activity, students might be encouraged to write their own sentences or short stories using words with the target phonics pattern. The key idea behind phonics through literature is that phonics instruction is embedded within the context of enjoyable and meaningful texts, fostering a love for reading and connecting phonics to authentic language usage. I found that my students were highly engaged in these activities, and they proved to be beneficial to their development as readers.

In summary, the teaching of phonics is a foundational component of early literacy instruction. It equips young readers with the tools needed to decode words, build fluency, and enhance spelling skills. However, the key to effective phonics instruction lies in balance — it's not about choosing between phonics all the time or not at all; it's about blending phonics into the fabric of literacy instruction.

By incorporating phonics into shared reading, fun activities, and explicit instruction, early childhood educators empower their students to become confident and skilled readers. In the next installment of our series, we will explore comprehension strategies, bringing us one step closer to unlocking the full potential of our young readers. Stay tuned!

Encourage meaningful reading habits as you ask students to engage in a dialogue with their text.

Over the past few years, I have heard more and more middle and high school teachers agree about how difficult it is to “get kids to read." I have observed myself that few students seem to be reading full length books independently, and by choice. Of course, there are so many reasons for these observations.

Let’s zoom out a bit to think about the state of reading for most of our students: in the past, reading was not only a major form of entertainment, but a crucial source of information. Time for reading was not in competition with an expansive, alluring digital world offering games, web surfing, Tik Tok, Instagram, endless TV and YouTube channels, etc. Even as adults, we know how easily accessible and comforting these modalities are. Technology offers us so many easy, even addictive options. Technology has also made it easier for students to “read” or pretend they have read an assigned text by scanning summaries of chapters, Googling quotations from the text, watching video versions, etc. Information that we may have needed to access by reading a book is now available at the click of a finger or by saying a few words to AI. We have all been there — we even have a term for this, tl;dr, or too long, didn’t read. Research confirms my own observations that few young people are reading on their own or consider “reading for pleasure." The Pew Research Center asserts that, “few late teenagers are reading many books” and a recent summary of studies cited by Common Sense Media indicates that American teenagers are less likely to read ‘for fun’ at seventeen than at thirteen.” The pandemic also seems to have derailed some students’ academic reading habits, which have proven to be like muscles that need to be exercised more regularly than we previously knew. All of this means that if we want our students to read, to become strong, confident readers, and maybe even enjoy reading, it is crucial for educators to make reading meaningful and relevant for our students, and not simply “cheat proof."

Encouraging students to read

Offering students choices of relevant books to read and discuss together in book groups or pairs is a fantastic way to encourage them to engage in reading. However, most educators agree that reading a book together — as a shared “anchor text” for the whole class — can also be important and lead to powerful discussions and collective learning. Mike Epperson — a teacher with whom I work closely in the South Bronx — took the opportunity to bring a shared anchor text to his 10th grade classroom, introducing his students to Elie Wiesel’s Night. While Night is a riveting, significant story and a relevant choice for 10th graders, who are concurrently learning about World War II and the Holocaust in history class, that doesn’t guarantee that students will engage in the reading. Mike was concerned about ensuring that his students were both engaged deeply and personally in the important subject matter and took it seriously. He decided early on that he wanted students to read the entire book. Mike strategically layered his teaching unit with Night at its core, along with supports and entry points to encourage high engagement, including: background building about the Holocaust, Anti-Semitism, and Judaism, and a careful sequence of lessons that focused on a key topic in a section of the book. Additionally, to encourage reluctant or less confident readers to read daily and remain engaged in reading the whole book, Mike emphasized and taught annotation. Since the school had copies of the book left over from ordering during the pandemic, Mike was able to give each student their own book to write in and keep. These two simple pieces — students having a book of their own and an opportunity to talk back to the text through annotation — created an environment ripe for close reading and high engagement.

Encouraging students to annotate

Getting students to annotate in their actual books wasn’t as simple as Mike had expected — he recalls that “when we first started annotating, some students expressed resistance because they didn’t want to make the nice-looking book look ugly. One student compared it to writing on a beautiful painting with crayon.” However, as time went on, students were “able to find a way to annotate that helped them preserve the beauty of the original text. I believe that as students took on a self-appointed role as the book’s preservationists, they ended up developing a deeper respect for the content of the book as well.” As the students connected more personally with the book and the character of Elie, Mike began to see that the act of authentic annotation was offering students an unanticipated opportunity for creative expression. He shared that “a lot of students like drawing, and there’s a similar appeal in annotation. While annotating is not drawing, a fully annotated page is visually pleasing. Some students’ annotations are neat, symmetrical, and visually appealing in a way that suggests that students take pride in how their annotations look. I think this fosters a sense of pride in the content of their annotations, too.” Mike’s observations of his students’ annotations confirm the belief that writing as you read makes your thinking visible, and can create an engaging conversation as we talk back to the text. He puts it simply: “Annotation gives the students a more active role in reading. They get to have a voice, even if no one else will see their annotations.” The students are no longer alone with a book. They are in dialogue.

Suggestions for successful annotation

When I visit Mike’s classroom, students eagerly show me their annotations and explain the significance of both specific lines on a page and their connections to larger themes. A number of students also tell me how much annotation is helping them “remember’ and “understand” past parts of the story. They are clearly proud of their text marking and meaning-making. Based on my observations of Mike’s classes, I’d like to offer some simple tips for making annotation a successful approach with your own students:

Hopefully, you will feel inspired to introduce or continue using annotation in your classroom! As you encourage students to read with their pen and engage in a dialogue with a text, feel free to adjust any of the strategies above to match the readers and annotators in your classroom.

Equip readers with the tools needed to recognize and manipulate sounds embedded within language.

This is the second installment in our Science of Reading series

As the science of reading becomes more influential in the field of education, it is important for us to not only accept and incorporate the principles in our practice, but also make sure we fully comprehend the essence and significance of what it means. Because I am an elementary educator and instructional coach dedicated to nurturing emerging readers, my commitment lies in breaking down the intricacies of the science of reading, while providing support for our young readers' development.

Phonological awareness — much like fluency, the topic of my previous article in this series — serves a crucial role in shaping a child’s reading journey. In this article, I intend to define phonological awareness and offer practical insights for fellow educators. Drawing from my experiences in the classroom as well as my own reading and research, I will explore its significance, its alignment within the science of reading, and provide guidance on fostering it effectively in early childhood settings.

Defining Phonological Awareness

Through my pre-service training, my experiences in the classroom, and ongoing reading and research, my understanding of phonological awareness has crystallized as the capacity to recognize and manipulate the sounds embedded within spoken language. Imagine it as a playground of sounds within the mind, where children identify rhyming words, dissect sentences into syllables, identify individual sounds (phonemes), and play with the rhythm of language. Like fluency, this skill is crucial, serving as the foundation for reading readiness. Strong phonological awareness equips children with the tools to decode words, comprehend texts, and eventually become proficient readers and writers. In essence, phonological awareness is akin to the scaffold that supports the acquisition of language, empowering children to construct sentences, paragraphs, and stories with confidence. It encompasses the following micro-skills:

Strategies for Supporting Phonological Awareness

Recognizing its significance, I have dedicated considerable time to identifying effective strategies and promising practices to support phonological awareness. Drawing from strategies I utilized as a third-grade teacher, coupled with observations from visits to flourishing early childhood classrooms, I want to share three promising practices:

These practices, while adding an element of enjoyment to learning, lay the groundwork for phonological awareness, preparing the stage for successful reading development.

Embracing Phonological Awareness

In the world of reading science, phonological awareness plays a vital role, mixing together words, sounds, and understanding. Just as fluency helps connect understanding and reading, phonological awareness serves as a crucial link between grasping the tiniest sounds within words (phonemic awareness) and linking these sounds to letters (phonics). When we nurture this skill, we help kids confidently deal with reading challenges and build on the fluency we talked about in article one. By recognizing the importance of phonological awareness and finding effective and engaging ways to teach it, we ensure every child embarks on their reading journey with a strong foundation, unlocking the power of literacy and lifelong learning.

Overcome common language learning myths to view multilingual students as assets, not liabilities.

Multi-Language Learners, or English Learners, are one of the fastest growing populations in our nation. Whether students are immigrating to the US anywhere in their journey from Pre-K to 12th grade, or English is not their primary language at home, educators are in need of support when it comes to language learning across grades and content areas. We examine this topic, dispel common myths, and discuss how to support these students in our Support for Multi-Language Learners episode of Teaching Today, where our host Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang is joined by Maria Garcia Underwood, Founder and CEO of M. Ideas Consulting, and yours truly, Lead Professional Development Coach here at CPET.

All terms for language learning are the same

In the episode, we highlight three key terms and define how they are different. Although these terms all have something to do with language learning, they are not synonymous. Here is a quick breakdown of what some language learning terms mean:

Throughout the rest of the episode, we use the term MLLs.

Teaching a foreign language is the same as teaching English

How we teach language matters when considering the context in which we are teaching. Teaching English when English is the dominant language of instruction requires different teaching practices than teaching a foreign language to students. Maria asks us to consider the motivator behind language acquisition when we learn our first language: communication. When thinking about our MLLs, their main goal is to “acquire English for communication purposes, for their everyday reality, for their everyday survival, both in those six hours at school, and outside.” This is very different from acquiring a language for the purpose of being able to communicate abroad when you’re on vacation or a business trip. Unfortunately, some of our teaching practices for English learning do not always mirror this basic need. Think about a one-year-old. Are you teaching that child grammar and verb conjugation? I hope not. That’s not how language is exposed to children. We focus on communicating, forgiving their mistakes, and ensuring their access to language grows. How can we use this model for our MLLs? Consider their basic needs. What do they need to understand and communicate throughout the school day to feel comfortable and safe? This ranges from understanding the school schedule to how they indicate the need to use the restroom. This contextualizes the language for them and creates the space to continue learning. We also need to consider the role of language when accessing content. As a high school English teacher, not only was I responsible for helping my students acquire a new language, I was also responsible for helping them learn how to write a personal essay for college applications. I worked with my bilingual students to create instructions on how to write personal essays and research papers in Spanish (the primary second language spoken at my school) because as far as I was concerned, the English could come later. Of course I wanted my students to feel confident in their English language abilities, but they also needed to understand the reasoning behind a thesis statement or how to use supportive evidence clearly. This content was essential, similar to the elements of a lab report or explaining a proof in math. Learning a language to access content is very different from learning a language as content.

It only takes a few years to master a language

To dispel this myth, we turn to the work of Dr. Stephen Krashen, an American linguist and Emeritus Professor of Education at the University of Southern California. He outlines five levels of language acquisition (different from state determined levels for testing) and an average timeline for transition:

As educators, we must consider how long it takes the average language learner to reach the Advanced Fluency level. We might hear students having conversations with their peers in the hallway, but those social situations require what Dr. Jim Cummins, professor for the Studies in Education of the University of Toronto, considers Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills, or BICS. These conversations require different skills from classroom language, which Cummins considered Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency, or CALP. Students who are able to use conversational language are moving through the levels of language acquisition, but educators must be careful not to assume that just because a student is fluent in social language, they are also fluent in academic language. For more information specific to BICS and CALP, check out Colorín Colorado’s page. If students have had interruptions in their education, you might hear the term SIFE associated with them, which stands for Students with Interrupted Formal Education. Interrupted schooling can contribute to slower fluency timelines and lower levels of literacy. Without strong language foundations, it can make learning another language more difficult.

“Exiting” means 100% fluent

Many states have different indicators that students are ready to “exit” language services, but this does not mean that they have reached the advanced fluency level. Usually, when students are deemed ready to exit, they are just broaching the intermediate fluency level. What does this mean for teachers? This means that every teacher is a language teacher and needs to consider the supports and scaffolds they are providing their MLLs throughout their curricula.

Literacy skills in a native language can’t transfer

As mentioned above, it takes about 7-10 years on average to become fluent in another language. What might speed this up? If students have proficient literacy skills in their native language(s), this understanding can help unlock another language. For example, they might understand how language functions, and know how to follow certain rules. The rules might be different, but understanding a language system and how it works is transferable knowledge.

It takes longer for older students to learn a language

It is a myth that older learners are not as competent at learning a language as younger learners. This myth is centered around the language that we hear. Younger students might feel more comfortable taking risks and producing verbal or written language more quickly, while older students might take a bit longer to demonstrate their learning. It is also important to note that older students — those who are around 13+ years of age — are more likely to retain their accent when speaking. This might make older students feel less confident or comfortable speaking, and talking with students about their accents and challenging the stereotypes about accents in our classrooms can help our older learners feel safe to take language risks.

You need a certification to support your MLLs

If you are new to language learning and want to serve your MLLs to the best of your abilities, we highly recommend checking out the work of Stephen Krashen and Jim Cummins, which is linked above. Need something to start with tomorrow? Here are some actionable steps you can take: Make your content comprehensible. You can do this in a variety of ways, but an easy way to do this is to use visuals. In my classes with MLLs who spoke three different native languages, rather than attempting to translate everything in those languages, I used pictures. I embedded videos. I had students create visuals for vocabulary words. This is something educators can do quite easily, and it has an incredible impact. Contextualize language. Think about how to show students when and where they might use this language. You can provide sentence stems, have students act out the language in short role plays, or attach physical movements to certain words. This also looks like providing a rich language environment, whether it’s encouraging discussion, think-pair-shares, or providing labels for students both in the classroom and within content instruction.

Shifting your mindset

At the end of our episode, we spoke about shifting our mindsets when it comes to our brilliant MLLs. I brought up a tweet I saw:

I think this ultimately comes down to a first language. For example, a native English speaker who is learning Mandarin and Spanish is seen very differently from a native Spanish speaker who is learning English. There are other biases that come into play, but that’s an article for another day. For now, I encourage educators to acknowledge that knowing multiple languages is an asset, not only for our students, but for our communities.

Navigate reading mastery and the science of reading to create meaningful instruction for young readers.

This is the first installment in our Science of Reading series

In the realm of reading instruction, fluency acts as a foundational cornerstone, shaping the way readers interact with written language. Often hailed as the bridge connecting decoding and comprehension, fluency plays an instrumental role in molding a reader's overall understanding. This article takes a comprehensive look at the concept of fluency, delving into its significance, practical implications, and its alignment with the science of reading, with a particular focus on the role of guided reading.

Defining Fluency: Beyond the Basics

Fluency in reading goes beyond just being able to read words correctly. It involves reading in a way that is smooth, precise, and with expressive intonation. It also includes accuracy in understanding the text, maintaining a suitable reading speed, and paying attention to prosody, which refers to the rhythm and melody present in language. When all of these elements come together, they transform reading from a basic recognition of words into a skill that allows you to effortlessly comprehend the deeper significance of a text.

Why Fluency Matters: Bridging Decoding & Comprehension

Fluency acts like a bridge that connects two important parts of reading: decoding and comprehension. Decoding is the process of breaking down written symbols into recognizable words, while comprehension involves understanding the true meaning of the text. When a reader becomes fluent, it means they can decode words effortlessly, which in turn frees up mental energy. This newfound mental capacity can then be directed towards better understanding the content of the text. Research has shown a strong connection between fluency and comprehension. Readers who have developed fluency are not only able to grasp complex ideas easily, but also engage in critical analysis of the text. This skill in turn helps them develop a genuine fondness for reading. This dynamic relationship between fluency and effective reading instruction is a central focus within the science of reading.

Guided Reading: A Path to Proficiency

In the array of strategies aimed at promoting fluency, guided reading emerges as a standout approach. Within a guided reading context, small groups of students engage in shared reading experiences, guided by their teacher. The strength of guided reading lies in its ability to:

Guided Reading in Action: Effective Approaches

Elevating Fluency: A Reading Journey

Fluency goes beyond a mere skill; it's the foundation of satisfying, meaningful reading. Guided reading plays a key role in nurturing this skill, supporting capable readers, and fostering a genuine passion for reading. As educators embrace the principles of guided reading and other fluency-centered approaches, they empower young minds to confidently navigate texts. This involves actively connecting and interlinking various elements within the text, much like weaving threads into a fabric. This journey blends the art of reading with the science of effective reading instruction, resulting in a community of skilled and enthusiastic readers. If you are interested in exploring guided reading further, join me at Best Practices for Guided Reading, which will provide you with an opportunity to experiment with designing and implementing guided reading lessons of your own!

Why simply adopting new programs will not guarantee improved reading scores.

Recently, the chancellor of New York City public schools, David Banks, announced a significant change in reading instruction by introducing three researched-based programs with a focus on phonics. While this shift aims to address the flawed approach to teaching reading, it also raises questions about the shortcomings of the current system and the potential consequences of relying solely on phonics instruction.

In this article, I raise concerns about the new programs, the importance of a balanced approach, and propose investing in professional development to improve existing efforts.

Flawed approach to teaching reading

David Banks criticized the City's approach to teaching reading as fundamentally flawed and failing to align with the science of how students learn to read. However, the exact shortcomings are not explicitly defined. Was it the lack of phonics instruction or insufficient emphasis on it? Furthermore, the effectiveness of the current approach seems to be evaluated based on standardized exam scores, which doesn’t provide a comprehensive picture of student learning.

New programs and concerns

The new programs being offered to schools, such as Wit and Wisdom, Expeditionary Learning, and Into Reading, each have their strengths and weaknesses. Wit and Wisdom emphasizes knowledge building but lacks explicit phonics instruction, requiring schools to adopt an additional phonics program like Fundations. Expeditionary Learning includes explicit phonics instruction, but Into Reading has faced criticism for its lack of cultural responsiveness. It is crucial to recognize that there is no magic bullet. No single program can meet the diverse needs of all students, and simply adopting new programs does not guarantee improved reading scores.

Maintaining foundational reading practices

I am not against explicit phonics instruction; however, I want to advocate for the preservation of foundational reading practices, such as read-alouds, independent reading, and shared reading — all of which promote fluency, comprehension, and vocabulary development. While phonics instruction is necessary, it should not overshadow these essential practices that nurture a love for reading and promote student autonomy when it comes to book selection. It is concerning to me that the science of reading is being equated solely with decoding and phonics, which I believe will lead to an overemphasis on this aspect of instruction. Given the limited time available for reading instruction during the school day, other important reading activities may be deprioritized or excluded altogether. This narrow focus could have negative implications for teachers, students, and their overall reading experiences. To teach reading comprehensively, it is essential to consider the interplay between different reading skills. Chancellor Banks highlighted five essential skills reflective of a competent reader:

But these skills are not sequential. They are interconnected and should be taught in a way that recognizes their interdependencies.

Investing in professional development

Rather than perpetuating the narrative of a reading crisis and introducing new programs in haste, I would urge us to invest in professional development for teachers and leaders. This approach would enable them to delve into the science of reading, understand its implications, and identify the most effective ways to teach reading skills. By focusing on all aspects of reading development — phonological awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension — current efforts can be improved, specific curricula can be adapted, and supplementary strategies can be identified.

Encourage students to expand their repertoire of ways to read and respond to literature.

As someone who loves to read and write, one of my favorite things to do is annotate texts — whether it be a few scrawled words in the margins of my most beloved hardcover books or endless questions written on sticky notes falling out of flailing paperbacks, my annotations capture the spirit of my hyper-personal engagement with a text.

When I became an English teacher, I knew that I wanted my students to learn how to annotate, in part because I wanted them to capture their noticings and wonderings as they engaged in their own distinctive reading process. In “Literature as Exploration” (1995), Louise Rosenblatt wrote that every person has a unique, transactional experience when they read a text, in which they “live through” something special. I think of annotations like mementos of this special reading experience because they capture a moment in time in the transactional experience that would otherwise be lost. Every time we read a text, even if it’s one that we’ve read hundreds of times before, we encounter a new transactional experience. As we annotate and re-annotate texts, we leave behind a trail of our reading experiences: our questions, thoughts, and wonderings. I desperately wanted my students to develop that experiential, transactional trail of their reading processes.

The Traveling Text

Imagine my surprise when I discovered, as a new teacher, that my students often responded to my call for annotations with, “I don’t know how to annotate!” or “Can you tell me what to annotate for?” or, worst of all, “I hate annotating. It’s a waste of time.” I can recall my naive shock when I heard my students respond in this way. In a desperate attempt to show my students the value of annotating, I began tirelessly modeling annotation strategies and my own methods of annotation, but doing so yielded little success. With time, I developed an incredibly simple strategy for teaching my students to annotate. Essentially, I stopped teaching my students to annotate through direct instruction and, instead, encouraged them to teach one another. This instructional strategy was, in my teaching, a solution to the problem of students feeling like they “don’t know” how to annotate or that annotating has “no purpose.” I call this strategy The Traveling Text (download here). The Traveling Text is simple, requires minimal teacher preparation, empowers students, builds community, and teaches annotation skills. And implementing this strategy with your students only takes four steps.

The impact of The Traveling Text

In my teaching experience, here are some of the impacts of this strategy on my students and our classroom community:

Teaching students to read for meaning (and for pleasure) is a daunting task. Often, our students come to us already feeling like they don’t know how to read and annotate literary texts in the “correct” way, one that highlights what a teacher or evaluator might be looking for.

The Traveling Text creates possibilities for students to expand their own repertoire of ways to closely read and respond to literature. But, even more importantly, the strategy encourages students to experience a sense of intellectual community and belonging with their classmates as they share with one another written artifacts of their own transactional reading experiences.

Envision contextualized, meaningful grammar instruction that links to authentic reading and writing.

When I began my first year of teaching English Language Arts, I was expected to teach my students skills that fell under three large umbrellas: reading, writing, and language. I quickly learned that “language” encompassed the teaching of vocabulary, punctuation & capitalization rules, and, you guessed it, the “teaching of grammar.”

In my teacher education program, I took no classes on the teaching of grammar. I felt somewhat confident about teaching reading and writing, but completely lost when it came to the teaching of grammar. I didn’t even have my own experiences of learning grammar as a student to fall back on; my only formal grammar instruction was a series of SchoolHouse Rock videos and long-gone worksheets from elementary school. In an effort to increase my confidence and improve my own practice, I began to read about the history of grammar instruction. I discovered that I was not the only one who felt an overwhelming sense of uncertainty about the teaching of grammar. The question of grammar’s importance has vexed people for centuries and continues to vex people today: what to teach, how to teach it, why to teach it. So, where did the practice of teaching grammar come from? And what could grammar instruction look like in the 21st century classroom?

A very brief history of teaching grammar

In the eighteenth century, the study of grammar was perceived as an exercise in mental discipline, intended to train the mental faculties of memory and reason (Applebee, 1974; Scholes, 1998). Grammar study focused on the learning of rules and their application. By the early nineteenth century, studies in specifically English grammar became a prerequisite for higher studies, not to be continued in college. Lindley Murray, often referred to as the father of English grammar, published Murray’s Grammar in 1795 and established many rules of “proper” use of the English language. Grammarians like Adam Smith, David Hume, Lord Kames, and Hugh Blair advocated for grammar instruction connected with the expressions of rhetoric: diction, style, figurative language, and so on. By the end of the nineteenth century, grammar continued to have a place alongside rhetoric, literary history, oratory, and spelling in schools and in colleges. In the early twentieth century, many scholars at colleges and universities abandoned grammar instruction because they did not believe in its “scientific value.” Simultaneously, grammar underwent a revival in school classrooms because teachers thought it would be a useful technique for studying literature and for acquiring foreign languages. In the latter part of the twentieth century, grammar instruction transformed. Rather than teach grammar skills in isolation from grammar books, scholars argued that the teaching of grammar does not serve any practical purpose for most students, and that it does not improve reading, speaking, writing, or even editing for the majority of students (Applebee).

The research: spotlight on a grammar case study

In “Examining A Grammar Course: The Rationale and the Result” (1980), Finlay McQuade conducted a qualitative research study of his own course entitled “Editorial Skills.” McQuade humbly admitted that he had read research papers that argued against the discrete instruction of grammar skills, but that he continued to teach an elective course for high school juniors wholly devoted to the practice. In the study, McQuade discovered that his students' scores on a grammar post-test were actually lower than their scores on a grammar pre-test for the course. He concluded, after this first-hand experience, that formal, discrete grammar instruction is ineffective and should be abandoned as a classroom practice. Citing McQuade, Constance Weaver, the author of Teaching Grammar in Context (1996), argued that we should teach aspects of grammar that are most relevant to writing, such as subject-verb agreement, sentence combining, and punctuation. Significantly, Weaver asserted that the most effective grammar instruction must arise organically from students' own writing: “teaching grammar in the context of writing works far better than teaching grammar as a formal system.” The main takeaway from McQuade and Weaver’s research is that grammar instruction must be contextualized and meaningful within students’ reading and writing. Grammar instruction should not be the discrete learning of grammatical “rules” because these rules do not translate into a superior command of language or communication.

Recommendations for 21st century learning

These recommendations derive originally from Constance Weaver’s writings (1996) that were then expanded upon recently by Jeff Anderson, a disciple of Weaver’s work (2017; 2021). They strive to make grammar instruction both contextualized and meaningful.

In the early 21st century, the question of how best to teach a standard English grammar shifted away from methods. Instead, scholars began to question whether a notion of “proper grammar” should exist at all. In “Why Revitalize Grammar?” (2003), Patricia Dunn and Kenneth Lindbloom argued that the teaching of a standardized grammar reflects a discriminatory power system that excludes other dialects and cultures. They believe our classrooms should be spaces of multiple literacies, celebrating a diversity of dialects.

With that said, the reality is that many teachers are expected to teach — or want to teach — their students “grammar.” Perhaps their rationale for doing so is similar to reasons from the past: it builds “mental discipline” because students have to learn and apply linguistic rules; it shows that one comes from a certain educational background, one that encompassed the learning of Standard English Grammar; it helps students to acquire new languages and to closely study literature. I think it’s important to note this tension between research and practice when it comes to the teaching of grammar. Since the 20th century, scholars like McQuade and Weaver have argued against the discrete teaching of grammar rules in the classroom, arguing that they are entirely ineffective and possibly detrimental to students’ learning. Yet, in practice, many teachers, including myself, are expected to teach grammatical skills. Without dismissing or diminishing this tension, I hope that these recommendations will aid in-service teachers as they continue to envision what grammar instruction can look like in the 21st century classroom.

Breaking down the science of reading to identify specific skills & supports for emerging readers.

Many people are talking about the science of reading — a term that is certainly not new, but has been gaining some serious traction recently, and prompting some heated debate. This debate largely stems from how this term is being interpreted and what this means for the students in our classrooms. What is truly meant by the science of reading?

After doing some of my own research, I’ve come to understand the science of reading as a comprehensive body of cross-disciplinary research conducted over the last 20 years that deepens our understanding of how the brain learns to read, including what skills are involved, how these skills are connected, and which parts of the brain are responsible for our reading development. The research seems clear, but because the term has become so loaded, I believe we are losing sight of what our young learners really need to become strong, capable readers.

What makes a skilled reader?

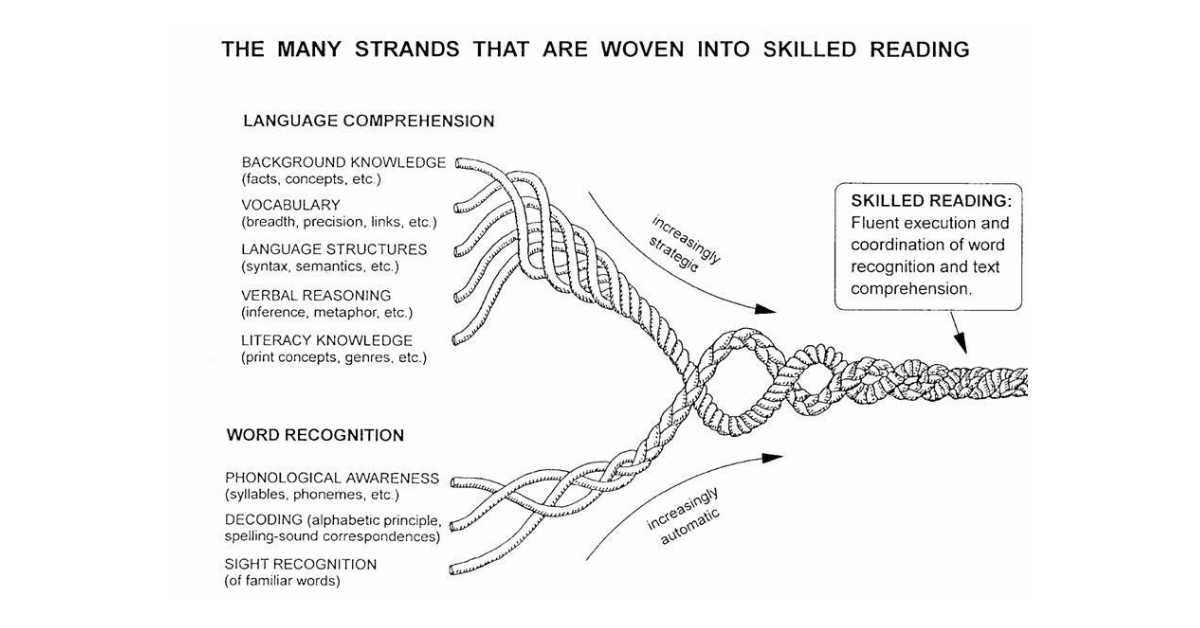

One of the leading researchers of early language development and its connection to later literacy, Dr. Hollis Scarborough, developed in 2001 what she termed the Reading Rope, which helps us articulate the specific skills readers need to have in order to be proficient. The rope consists of lower and upper strands, with the upper strand focusing on language comprehension, and the lower strand emphasizing word recognition. All these micro skills start to work together through practice and repetition, so that these skills can become instinctive. Ideally, over time, language comprehension becomes more strategic and weaves together with word recognition to produce a skilled reader.

I have greatly appreciated Dr. Scarborough’s work, and recognize connections to how I have and continue to talk about the reading development in my coaching work. Despite using a few different terms, we have similar meanings. What she describes as literacy knowledge, I have described as concepts about print. Similarly, we talk about comprehension as consisting of micro skills including vocabulary and background knowledge — the skills needed to make sense and meaning of a text.

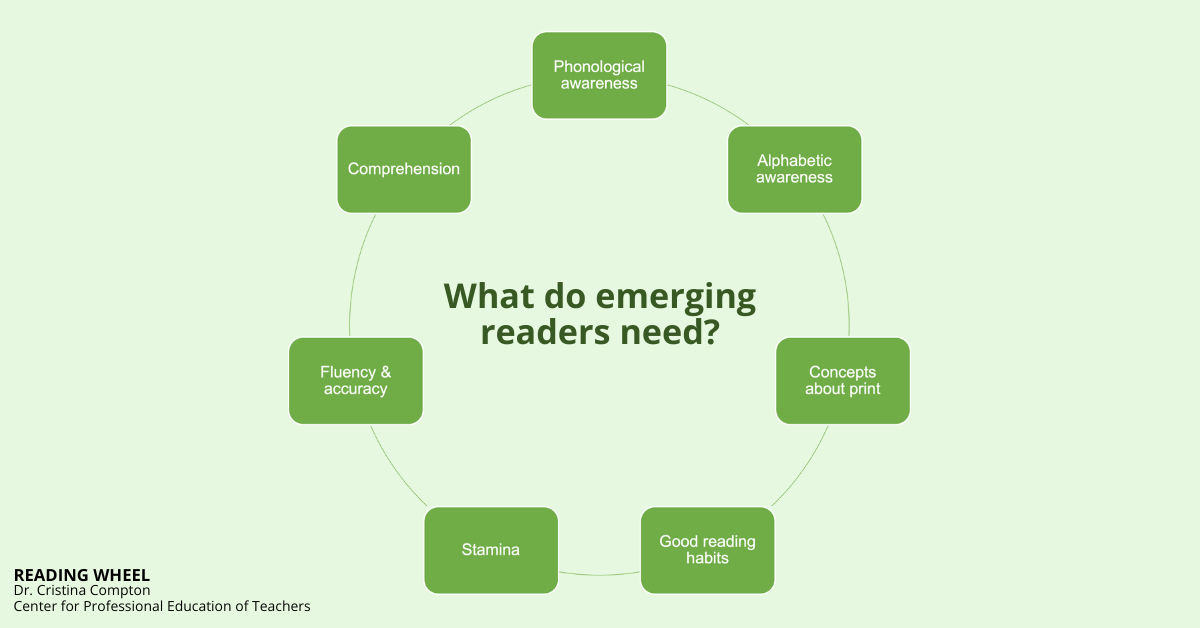

However, I have gone a bit further in my explanation of what emerging readers need and have developed the Reading Wheel, which is based on my understanding of research and my experience as a childhood educator, teaching students how to read.

You’ll see that, in addition to phonological awareness, I include alphabetic awareness, which is defined as “knowledge of letters of the alphabet coupled with the understanding that the alphabet represents the sounds of spoken language and the correspondence of spoken sounds to written language.”

I also discuss the importance of good reading habits, which include what Dr. Scarborough describes as verbal reasoning and a few others. Good reading habits are those often taken for granted skills that proficient readers use when reading — predicting, evaluating, questioning, clarifying, and monitoring for meaning, for example. In my work with teachers, I try to have them engage in the reading of a text, and then reflect on some of the moves they made while reading, to help reveal the habits they utilize most, and how these might be incorporated into their teaching. I also include a specific focus on stamina, which I define as the skill of being able to read for longer and longer periods of time, and the willingness to keep reading, even when it feels hard.

What support do readers need?

To me, all these skills are equally important. The problem arises when we place more value or importance on certain skills over others — e.g., word recognition over language comprehension, which has often resulted in phonics instruction, all the time! Phonics instruction has its place when it comes to helping children learn the relationships between the letters of written language, the sounds of spoken language and supports their phonemic awareness and decoding skills; however, phonics instruction alone would not suffice. Emerging readers need opportunities to recognize the word patterns and letter blends in context, as they show up in books. If we look closely at both Dr. Scarborough’s Reading Rope and the Reading Wheel, we’ll see that they underscore the importance of being able to read words AND make meaning, evident by the weaving of the individual threads of the rope and the circular nature of the wheel. Students need explicit instruction when it comes to developing comprehension skills, in order to support them in thinking critically, making connections, and developing their identity as readers. Young readers need differentiated instruction and in the moment feedback as they work to progressively read more complex texts. This often happens during readers' workshops, or small group instruction, such as guided reading. Lastly, children need opportunities to engage in independent reading and participate in read alouds, to gain exposure to a wide range of texts aligned to their needs and interests, to grapple with different topics and content, to help foster a love for reading, promote stamina, and learn meaningful habits from a skilled reader — their teacher. My students loved read alouds, and often begged me to read more, so they could find out if Clover and Annie end up as friends in The Other Side, or find out if and how the teacher will respond to the class making fun of Chrysanthemum, or find out the connection between Kissin’ Kate Barlow and the Warden in Holes.

As Diana Townsend states, “If we really care about teaching kids how to read, we need to focus on creating space and time for teachers to enhance their professional knowledge." They need time to explore the research around reading development for themselves and engage in conversation with colleagues about how it should inform their instructional strategies and approaches, rather than relying on a packaged curriculum or reading programs to do it for them.

Furthermore, there needs to be meaningful and ongoing inquiry, where teachers can try things out, and then reflect on what’s working, when, for which readers, and why, as we know it takes time and patience to get things “right.” At the end of the day, Townsend reminds us that, “no one is going to ‘win’ the reading wars and children will always be the losers.”

What does it mean to be mathematically literate?

Literacy is quite the term. When I started my teaching career as an English educator, I assumed that literacy was my domain. As I continued teaching and studying education, it became clear that literacy is all encompassing. I learned about the ways students could become literate in science, social studies, and more recently, racially literate. For some reason, none of these literacies seemed out of my reach, and then entered math. Math has always been a tough subject for me, and in this conversation, I was able to again sit down with Bob Janes, Secondary Supervisor of Mathematics for East Hartford Public Schools (revisit our first conversation, on equitable assessment, here), and talk about what literacy in math looks like.

How would you define literacy as a math teacher?

Literacy in math is the ability to understand and communicate mathematics in a variety of forms. I typically use the following definition from the The Connecticut Common Core of Teaching (CCT) Rubric for Effective Teaching 2017:

Thinking about the definition as conveying meaning and understanding meaning in a variety of forms, how does that show up in the math classroom?

It shows up in a variety of ways. I’ll go through a few different modalities. Reading Students should be able to read about a scenario or context and apply mathematical understanding to it, often called mathematizing, decontextualizing, or modeling. Students should also be able to read a mathematical text and understand common notations and representations. This includes algebraic notation, tables, charts, and graphs. We call these processes decontextualizing and contextualizing. Writing Students should also be able to justify their ideas in text using the same notations and representations that they are able to read (e.g. sentences, algebraic notation, tables, charts, and graphs). Speaking and listening Students should be able to listen, interpret, and critique their peer’s ideas. They should also be able to share and support their own ideas. Vocabulary Students should be able to recognize and use both Tier II and Tier III vocabulary with precision while reading, writing, speaking, and listening. Connecting representations This one is more math specific than the others. Students should be able to draw connections between different representations and understand when one representation is more advantageous than another. For example, suppose students were analyzing the freefall motion of a skydiver. A paragraph, an algebraic function, and a graph would all reveal different information about the scenario, and taken together, they provide a more complete understanding.

Unfortunately, I’ve seen the opposite of this in many math classrooms, what some might call “plug and chug”. If teachers are stuck providing worksheets and asking students to fill them out to “demonstrate mastery”, how can they change their classroom practices to ensure students are literate in mathematics?

We often shy away from giving our students tasks that ask them to read, write, speak, and listen in math class because we think that they will struggle. We also think that students who already find math content difficult will be completely exasperated by integrating literacy skills. Unfortunately, it is nearly impossible to build literacy skills in a vacuum. We must start by exposing our students to high-quality, standards-aligned tasks that promote the use of literacy skills. Then, we use literacy strategies to support students within the context of these tasks. There are a number of great resources out there to choose from when selecting tasks. Curriculums that are aligned with the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) for Mathematical Practice (MP) typically include opportunities for students to read, write, speak, listen, work with vocabulary, and draw connections between representations. My favorite curriculum to pull from is Illustrative Mathematics, and my two favorite instructional routines are Three Act Tasks and Which One Doesn’t Belong. A distinguishing feature of the tasks and routines linked above is that they all give students something to discuss or think about. This includes tasks that give students different starting information, tasks that have multiple solution methods, and tasks that have multiple answers. Robert Kaplinsky calls these approaches “Open Beginning”, “Open Middle”, and “Open Ended” and even has a website dedicated to these types of tasks.

This all sounds fantastic, but what if a high school student was not exposed to this kind of literacy in previous grades? What are some strategies teachers can use to help students develop math literacy?

I’ll talk through a few of my favorites, although there are a number of strategies and routines that are great for supporting student’s literacy skills. It’s important to understand that none of these strategies will cause immediate success. Students who are not accustomed to literacy in math class may struggle at first, but over time they will begin to use these strategies on their own. Reading I like to use the three reads protocol when reading word problems. Different groups have their own tweaks on the protocol (e.g. LAUSD, SFUSD, Kelemanik & Lucenta), but the structure is generally the same. Students read the first time to understand the context, a second time to identify important quantities, and a third time to interpret the problem. Students can also use annotations or highlights as they are reading to identify important information. When working on an interdisciplinary team, I like to use common annotations for text so that students can see the connections between subject areas; however, we can annotate more than text in math class. Tables, graphs, and even visual patterns are great places to make meaning through annotation. Writing Other disciplines have their own response structures such as RACE or CER. Just as with annotations, I prefer to use a common response structure with other disciplines. Speaking and listening I’ve found that talk moves can help students get started when they don’t know what to say. Talk moves can be prompts from the teacher, visuals for students to see, or both. Other educators use similar techniques such as sentence frames or discourse cards, and have created extensive lists of prompts and stems to get students talking. I think it’s up to the teacher to choose what works best for their students. I would be remiss not to talk about Building Thinking Classrooms by Peter Liljedahl. While not technically literacy strategies, I have observed the 14 practices in this book promote more student to student discourse than I have ever seen in a math classroom. It’s worth a read! Listening Many students find active listening and comprehension in real-time challenging. While this is the ultimate goal, technology such as EdPuzzle can be used to slow down videos and provide frequent comprehension checks. Vocabulary Vocabulary is one that I still personally struggle with. The traditional approach is to front-load vocabulary instruction, where a teacher explicitly teaches new vocabulary terms before they are used in context with the thought that students will not be able to understand the subsequent lessons without the vocabulary. However, I have found that many students do not need front-loaded instruction. Instead, many students learn vocabulary terms best when they are introduced only when needed, and when instruction is embedded within the context of the lesson. For example, students are asked to describe different parts of a graph and begin to use informal language. They might quickly discover that their informal language is imprecise and has limits. At this point, the teacher would step in to support students either with formal vocabulary or with an instructional routine that allows students to build their own vocabulary (e.g. Stronger and Clearer Each Time). In my experience, more students are able to attach meaning to the vocabulary using this approach than using the front-loading approach, but it will be up to the teacher to meet the needs of their students. Connecting representations Teachers should spend substantial instructional time for students to use, discuss, and connect representations. In the book Routines for Reasoning, Grace Kelemanik and Amy Lucenta suggest using an instructional routine to allow students to make connections and share them with their peers. Teachers can also be explicit about connections by using annotations to connect specific parts of each representation with arrows.

Is that it? Tasks and strategies?

All of this falls apart unless the teacher gives students specific and actionable feedback. It’s not enough for students to simply complete the tasks and apply the strategies we’ve talked about. Students need to know when they’re communicating effectively, and what they can do to improve. Error analysis routines and exemplars can be helpful in this regard.

What if teachers want to learn more?

There are a few places to visit if you want a deeper dive. The work done by Stanford University’s Center for Understanding Language (UL) is particularly helpful. They have developed a series of design principles and math language routines to support language and content development. Jeff Zwiers is the director of professional development for UL, and his website has even more tools to support authentic communication across the disciplines. More recently, The New Teacher Project (TNTP) created a Student Experience Toolkit for Math Instruction for Multilingual Learners that builds on the work of UL. These resources provide a great next step to learn more about literacy in math education.

Advanced AI has revolutionized writing, yes, but teachers don't need to fear being replicated or replaced.

As technology continues to advance, the field of education is not immune to its effects. One such area that is likely to see significant change as a result of advancements in AI is the high school English Language Arts (ELA) classroom. In particular, the emergence of AI language models like OpenAI's ChatGPT is poised to revolutionize the way students approach writing assignments and the way teachers grade them.

One major impact that ChatGPT is likely to have is in the realm of writing assistance. With its advanced natural language processing capabilities, ChatGPT can offer suggestions for grammar, spelling, and syntax in real-time, making the writing process much smoother for students. This can be particularly helpful for students who struggle with writing or for those who are learning English as a second language. ChatGPT can also provide students with suggestions for word choice and sentence structure, helping them to express their ideas more effectively. Another potential impact of ChatGPT on high school ELA classrooms is in the area of essay grading. Currently, teachers often spend a significant amount of time grading writing assignments, which can be a time-consuming and subjective process. With the help of ChatGPT, however, this process could become much more efficient and objective. ChatGPT's ability to understand and analyze language can allow it to grade writing assignments based on factors such as grammar, syntax, and coherence, freeing up teachers to focus on providing feedback on content and critical thinking skills. Of course, the integration of ChatGPT into the high school ELA classroom is not without its challenges. One concern is that relying too heavily on AI writing assistance could result in students becoming overly reliant on the technology and losing their ability to write effectively on their own. It will be important for teachers to strike a balance between utilizing ChatGPT's capabilities and ensuring that students are still developing their writing skills through independent practice. Another concern is the potential for ChatGPT to perpetuate biases in language and writing. For example, the model has been trained on a large corpus of text that reflects the dominant cultural and linguistic norms of the internet, which may not accurately reflect the diverse experiences and perspectives of students. Teachers will need to be mindful of this and actively work to promote inclusivity and equity in their writing assignments and grading practices. In conclusion, the integration of ChatGPT into high school ELA classrooms has the potential to significantly impact the writing process for both students and teachers. With its advanced natural language processing capabilities, ChatGPT can offer valuable assistance with grammar, spelling, and syntax, as well as provide objective grading of writing assignments. However, it will be important for teachers to balance the use of AI with traditional writing practices to ensure that students continue to develop their writing skills and that inclusivity and equity are promoted in the classroom.

Everything that you have read up to this point was produced by ChatGPT in less than 32 seconds.