|

Engage in low-inference observations that can lead to new discoveries about your students' needs.

Behavior is a form of communication.

Plug this sentence into your preferred search engine, and it will return enough results to keep you reading for hours. Since it’s more likely you’re scrolling through this post on your train ride, between classes, or at lunch than sitting with a cup of tea and hours to spare, let’s connect the dots quickly and consider a way to look at communication through behavior as data that we can analyze to determine a productive possibility in our classrooms.

Collect the data: what is the behavior?

Start with documenting low inference observations of behavior. As you jot down the description of the behavior, challenge yourself to write only what is observable. When you write, “a fight broke out,” ask yourself, “what did I actually see?”. What did you see? What did you hear? It’s worth the time it takes to develop your low inference observation skills, because you will be working from more accurate data, as free of assumptions as possible.

Analyze the data: what might it mean?

While you already have classroom expectations clearly outlined and students may be fully aware of the consequences of certain behaviors, whether it is a phone call home, a visit to the AP, or other intervention, you may also consider using a tool to support your own problem-solving. This is especially helpful when you’re confronted with a persistent, or even new, behavior. Lifelines is a tool we’ve used with our partner schools when looking at data reports together. With a few customizations, we can use this tool to explore behavior as data.

Consider possibilities: apply analysis to inform instruction

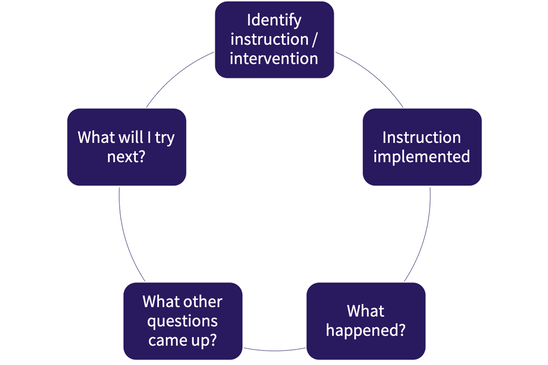

What questions, lessons, or interventions make sense to support the student and their learning? Is it an individual moment that is needed or could the whole class benefit from some time investigating this issue together? Try your lesson or intervention out. What happened? What other questions came up? What might you try next? If you continue to remain curious, your “final” determination in the Lifelines tool can be a starting point to a simple cycle of inquiry.

By engaging your curiosity and making low inference observations of student behavior, you can engage in an inquiry cycle that could result in new and exciting discoveries about what your students’ behavior is communicating. Your findings can then support students academically by addressing their social-emotional needs.

|

|

The Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) at Teachers College, Columbia University is committed to making excellent and equitable education accessible worldwide. CPET unites theory and practice to promote transformational change. We design innovative projects, cultivate sustainable partnerships, and conduct research through direct and online services to youth and educators. Grounded in adult learning theories, our six core principles structure our customized approach and expand the capacities of educators around the world.

|

ABOUT US

525 West 120th Street, Box 182 New York, NY 10027 416 Zankel Ph: (212) 678-3161 cpet@tc.edu Our Team Career Opportunities |

RESOURCES

Professional Articles Ready-to-Use Resources Teaching Today Podcast Upcoming PD Opportunities |

COACHING SERVICES

Custom Coaching Global Learning Alliance Literacy Unbound New Teacher Network Student Press Initiative |