|

Why creating intentional groups can help match each student to intellectually engaging tasks.

Group work is important.

Group work is also hard. It can feel discouraging when we initiate group work and then it doesn’t go as planned, with some students opting out of the assignment while others carry the weight of the task for everyone. Teachers know that when they have a wide range of students with different learning needs, they can differentiate their instruction. Differentiation often includes creating multiple entry points to content and skills through group work, and we often see differentiation strategies like heterogeneous or homogeneous grouping used to differentiate instruction. But how do we determine which method will help our students reach their learning goals? Which types of grouping are best for which instructional strategies?

The case for homogeneous grouping

Whether matching students in pairs or small groups, homogeneous grouping happens when teachers enlist students with similar learning traits to work together to complete a task (either individually or together). Homogeneous grouping should be informed by data, like students who earned similar scores on a diagnostic assessment, had similar responses in a class assessment, or who shared a misconception about a previous lesson. It's valuable to match similar students together to complete a task that is designed to meet their learning needs. Homogeneous grouping is ideal when the teacher has designed a unique task for each group, is providing a unique text for each group, or has differentiated the content so that groups are aligned with content information they need to examine more closely. When students are in homogeneous groups, the tasks, topics, or texts they work with should be diverse. This becomes an effective practice because teachers are strategically matching similar students’ with a task that is designed specifically for them. When each group of students is working with a task or topic on their level, they’re able to increase their completion rate, feel confident about reaching their learning goal, and refine their thinking through discussion.

Example

A math teacher realizes that their students had a wide range of responses to adding and subtracting fractions on a formative assessment. Some students are completing all of the addition and subtraction questions with fluency and accuracy. Other students are struggling with subtracting, but showed proficiency with addition, while others are still struggling with the concept of fractions as well as how to add and subtract. With students performing within these three profiles, the teacher develops a lesson where students are grouped homogeneously and matched with a task that is specific to their learning needs:

By differentiating by student need in homogeneous groups, the teacher is able to match a task strategically to students in their zone of proximal development, which should increase their understanding of the content, create opportunities for success, and increase confidence.

The case for heterogeneous grouping

Homogeneous groups are an important strategy to use, but using them exclusively can be limiting to students. Not only is it important to develop community across a whole class, it’s also important for students to learn from one another and have opportunities to teach each other. Diversifying group structures to include mixed ability or heterogeneous groups gives students exposure to a wide range of voices, and keeps students connected to the class community. Heterogeneous groups are best matched with complex tasks that have multiple components. Within the group work structure, students can self-select or be assigned roles based on their areas of interest, as well as their performance. Working in a heterogeneous group allows them to build on each others’ ideas, and develop a product as a team, which is effective, memorable, and can be personally rewarding. Group roles or independent tasks are highly effective in heterogeneous groups and teachers will want to design the task so that every group member can take on a component that they can complete successfully. Jigsaw groups are a great structure to use for heterogeneous groupings. Within a jigsaw group, the group task is divided into multiple components (one for each student representative), and then brought back together when students inform their team of what they’ve learned. These components might be content-specific (e.g. each student represents a different character from a book, or a different type of problem solving in math). They may also be leveled by text (students divide out leveled texts on the same topic and collaborate on their understanding after reading). The easiest way to organize jigsaw groups is to strategically match students using a grouping strategy.

Example

If there are six groups, each student may be assigned a group number, and a letter which is matched with a task. Group 1 might have students matched with 1A, 1B, 1C, 1D, 1E, 1F (each letter representing a different task). Students then move into their letter groups (Group A would consist of students 1A, 2A, 3A, 4A, 5A, and 6A) and complete their task. Once they complete their task, students rejoin their number group to share what they’ve learned and complete the shared task or discussion. In heterogeneous groups, every student is matched with a task that is at their instructional level, and they use what they’ve learned to complete the shared task.

While homogeneous and heterogeneous groupings are some of the most common types of groups, they aren’t the only way to develop strategic collaboration for students. We can also consider grouping based on areas of interest, social dynamics, or even special gifts and talents. What’s most important is that when asking students to work together to complete a task, we are thoughtful and strategic about who should work together, what goal we want them to accomplish, and how we match them to an intellectually engaging task to reach that goal.

Find practical ways to strategically customize learning pathways for your students.

Differentiating Instruction is the practice of customizing instructional resources, tasks, texts, and topics to meet the needs of students with different learning levels and academic needs. With good intentions, curriculum developers identify grade level expectations and design unit and lesson plans with the ideal student in mind. Those ideal students started the year meeting grade level expectations, speaking the language with fluency. They all attend class every day and comprehend the lesson at proficient standards. They carry with them all the skills from the last unit into the next, and they learn at an even pace throughout the school year.

The problem is that these ideal classes don’t actually exist! This is why it’s so important to differentiate instruction. Students can’t learn when the course material is too difficult — they get frustrated, insecure, and eventually develop avoidance behaviors that cause learning disruptions or disengagement. But the flip side is also true — students can’t learn when the material is too easy! When there is no learning challenge, students get bored, overconfident, and they also develop avoidance behaviors resulting in learning disruptions or disengagement. Differentiating instruction is about the art and science of matching students with their just-right task, text, and topic. When we begin thinking about what we need to know about our students to effectively differentiate, it can get very overwhelming very quickly. The idea of creating a unique lesson for 30 students 4-5 times a day is an insane amount of work. The good news is that highly effective differentiation doesn’t mean that we have 30 different lesson plans — but it does mean we are using data to inform instruction, and customizing learning pathways strategically for our students.

Differentiating deliberately

There is no one perfect way to differentiate instruction, which is one of the things that makes it challenging. Because there are so many options and opportunities for learning, it’s easy to become overwhelmed with all of the different types of choices that can be made when customizing instructional materials for our students. Our Differentiating Like a Star resource is designed to help you streamline your thinking process, and provides a dynamic menu of options for teachers to use while planning differentiated lessons. On the matrix, there are four styles of differentiation: by data, by task, by text, and by team or group. The matrix provides recommended differentiation strategies aligned with each approach, and increases in complexity and effectiveness. If you are able to implement any strategy on the matrix, you’re differentiating! The goal is to develop our practices so that we not only use multiple differentiation strategies, but use them deliberately to meet a specific learning goal.

Tips & tricks

Differentiation done well appears effortless, but it takes a lot of work behind the scenes. Careful planning, analyzing student work, and setting clear learning objectives can help us to develop a pathway of differentiated experiences that are targeted to meet students’ needs.

Data-informed decision-making that creates groups of students who work collaboratively for a specific purpose.

From the one room schoolhouse to the giant lecture hall, the image we often conjure of teaching is of the sage on the stage, the professor imparting wisdom on the entire student body who are hanging on our every word. But the reality is that whole class instruction is rarely effective as a meaningful and sustainable learning experience. Students’ academic knowledge and skills grow more when they’re personally engaged in a task or challenge that meets their learning needs, supports their learning differences, and is customized to help them get to their next step.

Educators can often become overwhelmed with the prospect of differentiating instruction for every single student in the classroom, and often feel frustrated having to design 30 different lesson plans. The good news is that while students do need instruction to be personalized to meet their needs, many of their needs are similar. As educators, we want to better recognize our students’ academic, social, emotional, and skill-based needs and strategically match them with other students in the class.

Strategic grouping

There’s a big difference between working in a group, and working with a group. In an effort to increase group work and collaboration, we will sometimes push desks together so students are sitting in a group, and then give them permission to talk to their groups while completing an individual task. While this is community-oriented, we can differentiate it from working with a group on a shared task.

Strategic grouping is a key feature in teaching effective collaboration skills, and in streamlining instruction to meet the needs of our diverse learners. Strategic — or purposeful — groups demonstrate that we’ve put some time, energy, and thought into who students should work with. We can consider factors like literacy or numeracy performance, communication styles (introvert/extrovert), skills and talents (artists, writers, organizers), and even gender considerations for creating groups that are similar or mixed. One of the reasons strategic grouping is so difficult is because it requires us to know our learning outcomes, and to develop a strategy about the best ways to achieve this outcome. If I’m working on a unit where students will need to write an essay from a text they’ve read, I have to determine:

We can only answer these questions in the context of the class, the unit, and the end goal of the assessment.

Flexible grouping: number, color, shape

One of the most effective ways to establish strategic groups is to create groups that are flexible.

Developing strategic groups requires time and effort! And once groups are established and the students begin their work, it doesn’t mean that it will feel immediately successful. Just like any teamwork approach, groups take time to develop relationships, build trust, and establish healthy and productive routines. When groups change rapidly, even groups that are strategic, it makes it difficult to see the return on our investment. That’s why establishing strategic (purposeful to the context and task) and flexible groups can be a major win. One easy approach to flexible grouping is to design Number, Color, Shape groups. With a little bit of planning, we can set up three types of group structures at once. To establish flexible groups, consider three types of groups that need to be made:

Numbered pairs

Having students work in leveled pairs is an effective way to differentiate. By working with a partner, students can tackle more complex tasks, collaborate with a peer, or edit and revise their thinking as they complete an assignment. Students will also be able to develop more personal connections, which keeps them engaged and interested.

To set up numbered pairs, look at a class list and divide the total number of students in half. 30 students = 15 pairs. Then, begin matching students based on data — performance, reading levels, and personality can all be helpful data points to make matches. Once every student is in a pair, introduce the learning pairs by passing out numbered cards and invite students to find their match. It may be helpful to place numbers around the room so students know where to find their match, or create a class challenge to find partners without speaking. Once established, keep these numbered pairs for an extended period of time. Consider 4 - 6 weeks for pairs, given that it will take a few work periods before students feel comfortable, and once the pairs are working, making changes to the partnerships can derail the momentum. If some pairs don’t work out as planned, make specific changes in those situations.

Same shapes

After students spend time working in pairs, their collaboration and communication skills will improve over time with their partners. We can take our differentiation to the next level by joining the numbered pairs into small groups of 4-5 students with similar ability levels.

Maybe you’ll combine groups 3 & 8 to create a square group, and groups 2 & 9 to become a circle group. Same shape groups will create leveled groupings that allow us to differentiate topics, products, processes, and text levels by assigning a specific task to each group based on their Zone of Proximal Development. If we know that groups 3 & 8 are composed of students who are reading 2-3 grade levels below expectations, we can assign the square group a text that’s at their instructional reading level and have them complete the same critical thinking task that the other groups are assigned. If we know that groups 2 & 9 are composed of students who are reading at or above grade level, we can assign them a more challenging text on the same topic, and have them complete the same critical thinking task that the other groups are working on. Same shape groups work well because after their discussion and group work, the class can come together to discuss the larger topic, without limiting the contributions of students with below-grade level reading skills.

Color blends

Many — but not all! — learning goals are best accomplished by having students work in groups with peers on similar levels. When students only ever see examples of tasks and work products that reflect the same thing they would produce, they don’t have an opportunity to visualize how they can expand their thinking, reading, writing, or reasoning skills. By working with students in mixed ability (heterogeneous) groups, students of all different levels can participate in a jigsaw discussion or group projects. Mixed groups allow students to learn from one another, and play an individual role towards a shared goal.

We can create Color Groups using our Numbered Pairs and Same Shape groups as a starting point! Color Groups will be strategic, data-informed heterogeneous groups that can meet together consistently through a unit or term. To create the Color Groups, review the students in each Shape Group and begin distributing them evenly into Color Groups. Example: We can take one student from the square group, one from the circle group, one from the diamonds, and one from the hearts, and place them into the Purple Group. Because we’re mixing and matching from the Same Shape groups, we’re guaranteed a mix of performance abilities in the Color Blend Groups.

Bringing it all together

Strategic grouping requires data-informed decision-making to create flexible groups of students who work collaboratively for a specific purpose.

By designing these three sets of groups at one time, you can maximize your planning and minimize chaos! No more numbering off from 1 - 4 around the room. No more wandering around to find a partner. No more kids sitting in the back because they don’t have a group. If each student received a card on color cardstock, with a printed number, cut out in a specific shape, they could receive multiple group assignments within seconds. And after each grouping has been established, they’ll begin to learn how to work together for a purpose in each grouping they experience.

This is a difficult time for many of us, and students, undoubtedly, have been intensely impacted by shifts in education over the past year. Our ability to support and differentiate instruction for English language learners has shifted as well. As they've migrated to online classes and navigated new ways of learning, they are likely looking for additional guidance on their language learning journey.

This resource is designed to help students who are still acquiring English language skills and need extra supports for self-study. Language learning requires extra attention and focus, and this can be exceptionally hard when learning independently or at home. In this collection, we have compiled some of our favorite and most useful resources for guiding and supporting learning both within and outside of the classroom. Links, descriptions, and advice for using each resource are included. We hope this collection can help to guide those who may be struggling with language learning, especially in the ELA setting. We know how difficult it can be to learn a new language, and hope that these resources can help facilitate an elevated learning environment and a comprehensive approach to leveling the learning environment for all of our amazing learners.

To access additional free K-12 resources from our team, please visit our Resources page.

Thoughtfully design instruction that supports students at each stage of learning.

Differentiated instruction aims to meet the diverse needs of students, but it can be difficult to design lessons that support those who are struggling without restricting learners who are ready for more advanced study.

The Rigormeter’s spectrum approach, which re-envisions Bloom's Taxonomy, offers a straightforward outline of six learning stages, along with suggested actions for student engagement in each phase of the learning process. Like an odometer, the Rigormeter measures progress that builds from one stage to another. By de-linearizing Bloom's levels of knowledge, the Rigormeter highlights that learning can occur along a continuum, which can be traveled in more than one direction, with stops along the way. This approach implies that once we’ve reached the end, we might easily begin again. The Rigormeter is not just a method of measuring understanding — it can also be a map for planning instruction. If we conscientiously design our instruction to support students at each stage of the spectrum, we have the opportunity to see students thoughtfully engaging in the learning process, finding success at each stage along the way because they were properly prepared. Teachers who aim to challenge their students beyond their initial understandings can utilize the stages within the Rigormeter to design activities and lessons for further depth of study.

To access additional free K-12 resources from our team, please visit our Resources page.

Creating multiple pathways for students to approach their learning will allow them to increase their personal and academic engagement.

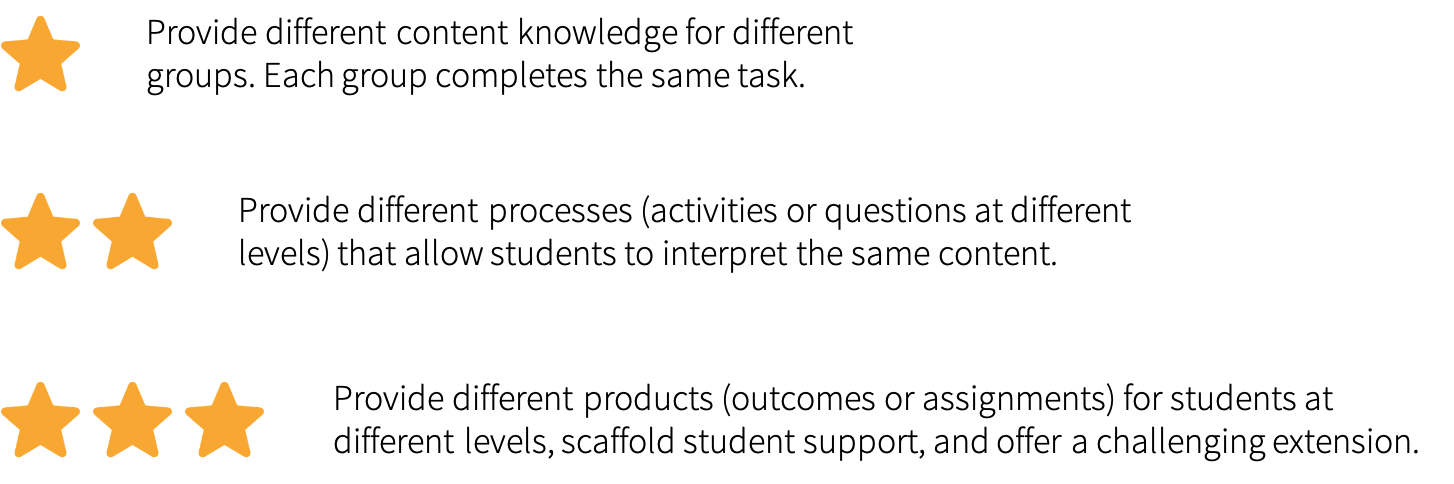

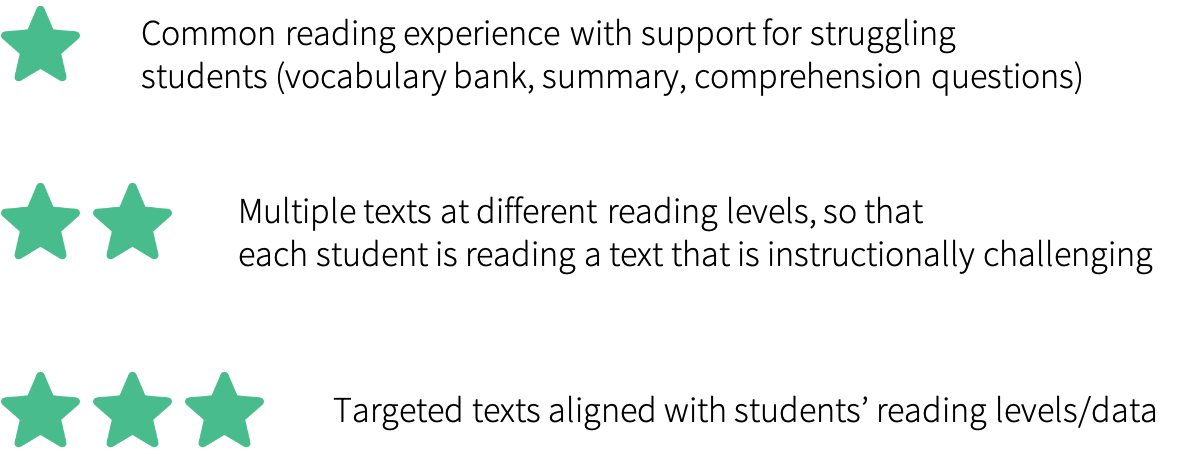

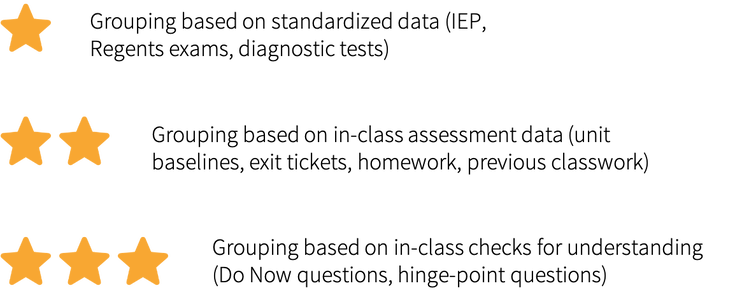

Differentiation can happen in many ways, with varying levels of complexity. Our Differentiating Like a STAR resource, designed to help educators consider entry points to differentiation, offers strategies in four categories: data, task, text, and grouping. Within each category, we outline three levels of instruction — the more stars included, the stronger the differentiation. By identifying pathways to expand differentiation, you can add depth and complexity to your lessons.

When teaching in person, we differentiate tasks by dividing content material, offering multiple processes to fit students’ learning styles, or varying the product to ensure interest and engagement. Differentiating at a distance may change our communication methods, but it doesn’t need to change our commitment to student choice. In fact, it can enhance it!

Pathways for differentiation

One classic way to differentiate instruction is to create different paths for students to demonstrate their learning. There are three ways that educators can differentiate based on the assigned task: content, process, or product. Content As you develop your curriculum, you may identify a series of content strands that students should be familiar with, and that are representative of a larger concept or theme within your instruction. When we differentiate content, we can identify some concepts and examples that are necessary for all students to know deeply, and other concepts that students should be familiar with, but may not be required to know in-depth. Differentiating this content allows educators to present a wide range of examples or scenarios as a means to teaching towards a larger concept. When differentiating content, every group takes the same steps to complete the same final product — but they begin with different content information. For example:

Product Sometimes, it is in students’ best interests to focus on the exact same content, particularly when content strands are essential to students’ understanding of a discipline, or are represented on mandated assessments. In these cases, we can keep the content the same, but invite students to represent their learning in different ways. By giving students choice in how they demonstrate their learning, we help them to tap into their natural creativity, curiosity, and intrinsic motivation. When differentiating products, it’s important to develop a scoring guide that focuses on the key content concepts that need to be represented, and to align each product outcome with those expectations. For example, you might present your students with three project options: a three-page essay, a PowerPoint presentation consisting of 10 slides, or a three-minute video. Each project can be evaluated based on the same content information and should demonstrate the same application, analysis, synthesis, evaluation, or collaboration skills. Process When preparing students for rigorous, high-stakes assessments, you may not have the freedom to pick and choose the content or the final product. In these cases, you can look at opportunities for differentiating students’ processes. Consider differentiating through process by providing various supports for students. Perhaps some students receive a glossary of key terms & definitions, while others receive a word bank, and others receive no vocabulary assistance at all (because they don’t need this additional support to make sense of the content). You can also use student notes to support process differentiation — consider inviting some students to make use of outlines, while offering two-column note taking, webs, and bullet points to others. Whether they’re working individually or in small groups, giving students a choice of how to engage in their learning process can feel highly personalized, which will enable them to walk with their best foot forward.

Making the most of online learning

When working in the world of remote teaching or blended learning, our typical teaching strategies may seem difficult to translate, which leads to defaulting to whole-class instruction that does not leverage student choice or differentiate based on student needs. But the online space offers just as many — if not more — opportunities to differentiate the task. High-Tech Many educators working in communities with on-demand access to technology are able to differentiate a task through content, process, or product using their online platform. Whether you’re using Google Classroom, Canvas, Blackboard, Moodle, or your own website, you can offer options at key points along the learning journey. In fact, it’s even easier to provide task options through distance learning, since there are no printing requirements! Within each lesson, we can create opportunities that maximize student choice. In high-tech spaces, we can post multiple assignments, graphic organizers, or focus topics and invite students to choose which they’d prefer to work with. Students can even work across class periods and be grouped with students who have shared interests, levels, or thinking processes. Students can also meet virtually through video conferencing, create small group videos, or share their process notes through pictures, video reflections, and digital artifacts. Low-Tech Some students have access to technology, but experience limitations due to time on their device, internet access, or support with using advanced features of applications. In these situations, the differentiation of content, process, or product should be made clear to students in their assignment. They may benefit from having their assignment personalized for them, and they may need flexibility if they are able to mix online and offline work. This can mean posting the task so it can be downloaded for later use (rather than just existing on a website), and creating materials that students can complete using their computer, but that don’t require internet access. No-Tech Students in the “no-tech” access category likely have less than one hour per day to access the internet, and may be logging on from a phone or tablet that isn’t connected to a printer or scanner for managing hard copy printouts. Teachers can offer entry points for these students by creating custom materials using picture models or short videos that explain what and how to complete a task with the materials they have on hand. Keep in mind that no-tech assignments can ask students to write out their responses by hand and submit assignments using photos. These assignments might also include packets of strategies or resources that can be picked up at school (and for convenience, can be picked up/dropped off during the same hours as food distribution), phone calls or text messages to students, or the option to send/receive materials by mail.

Differentiating tasks is one way we can increase student interest. Students are drawn to tasks that are personally relevant and challenging — creating multiple pathways for students to approach their learning (process), demonstrate their learning (product), or customize their learning (content), will allow them to deepen their understanding and increase their personal and academic engagement.

High, low, and no tech approaches to differentiating instruction through text selection and literacy support.

Differentiation can happen in many ways, with varying levels of complexity. Our Differentiating Like a STAR resource, designed to help educators consider entry points to differentiation, offers strategies in four categories: data, task, text, and grouping. Within each category, we outline three levels of instruction — the more stars included, the stronger the differentiation. By identifying pathways to expand differentiation, you can add depth and complexity to your lessons.

Differentiating instruction through text selection and literacy support is essential during a time of remote or blended learning. While learning remotely, students increasingly rely on learning through reading, rather than in-person lectures or teacher presentations. As students are exploring new content through texts, we can design multiple entry points to support engagement, content knowledge, and skill development. We use texts to inform our instruction at three critical levels:

When teaching in person, we often differentiate for students based on their reading levels. We may be used to differentiating a text by using a common reading support like a vocabulary word bank, or guiding questions to build comprehension. More advanced forms of text differentiation include providing multiple texts on the same topic and allowing students to make a selection. This ensures that students will have access to the main content information at the reading level that is the best fit for them. When we’re providing the highest level of differentiation for students, we’re matching specific students with an “on-level” and a “stretch level” text to support their understanding of the content and stretch their reading level.

Whether we’re teaching in-person or remotely, our biggest challenge is finding meaningful texts at different levels. You may be interested in exploring websites like Scholastic, Newsela, or Readworks — each of which offer access to texts organized by subject, topic, and grade level. A strong practice would be to identify the following:

If students are struggling with the lowest leveled text, consider adding additional scaffoldings (like the word bank or anticipatory summaries).

High-tech differentiation

We define "high-tech" as unlimited, individual access to an internet-connected device. Provide vocabulary support: Consider linking to sites like vocabulary.com, where you can create class lists, group students, and customize vocabulary lists (or select from pre-made options). You can also use this option to create quizzes and other vocabulary-building games, which will provide a complement to any reading assignment. Build student choice and autonomy by offering students a central text — for everyone to read — and then inviting students to contribute to a classroom library by finding two additional texts on the same topic. Going forward, students can select the texts they want to read based on those that have been identified for the class’ digital library. Use a formative reading assessment to identify targeted texts that can be incorporated into instructional tasks. We can use a resource like Google Forms to develop a differentiated task for students, and embed a select passage from the text into the form itself, while asking questions related to comprehension. If students answer the questions incorrectly, they can be routed to a text that’s targeted for a lower grade level. If students submit a mix of correct and incorrect responses, they can be routed to a text that matches their grade level. If students answer all questions correctly, they can be routed to a higher level text. Whether providing access to vocabulary instruction that’s parallel to the reading, or helping students discover texts at their own levels, differentiating by text level is a great way to ensure all students have a way to access the lesson.

Low-tech differentiation

We define "low-tech" as at least one hour of individual time on an internet-connected device. Add hyperlinks to potentially difficult words embedded in a shared text. This type of vocabulary support makes it easy for students to view the definition of a word, without leaving the document they’re reading. If you’re preparing an assignment in Google Docs or Word, simply highlight the word you want to define and add a hyperlink to an online dictionary. Help students utilize this support by asking them to summarize key parts of the text or define some of the vocabulary terms in their own words. This option does not require that students spend more time online, and will allow them to complete the assignment on paper rather than on the computer if that’s a better fit, given their access to technology. Offer student choice when posting an assignment to your online learning platform. Consider providing 2-3 texts as options and giving students a choice of which they’d like to read, or plan to strategically assign texts to students based on their reading levels. You can also invite students to read two out of the three texts, and offer additional points for reading multiple selections. Each interaction will help students absorb the content information, build their vocabulary, and challenge them to stretch to the next reading level. Teachers are sometimes cautious when doing this in person, as it can stigmatize students and highlight their level of academic performance. But in a remote learning setting, each task can become personalized, and this strategy can be implemented without these same concerns.

No-tech differentiation

We define "no-tech" as less than one hour on an internet-connected device. Add-on resources can accompany your lesson, and create scaffolds and supports for students as they read. For example, if a task includes a reading passage, comprehension questions, and a short response, you can create an add-on resource for vocabulary, which will provide definitions of words included in the passage. At a minimum, this word bank can help students make sense of the passage. For additional credit, we can ask students to create visual definitions of the vocabulary words, or define them in their own terms. Their work can be created using pen & paper, and then submitted by taking a simple photo. Ask students to synthesize content in their own words: Similar to the low-tech option, this begins with offering multiple texts as part of your assignment, and inviting students to choose the text that’s the best fit for them. From there, we can ask students to share what they’ve learned by writing about the topic as if they’re passing on their knowledge to students who are at a lower grade level. For example, if I’m teaching middle schools students who are learning about the three branches of government, I can extend my students’ reading task by asking them to write an explanation of this topic for third graders. The translation of the information from an on-level text to students at a lower grade level will help students think critically about what they understand.

Whether we’re teaching in-person or online, differentiating texts for students’ reading levels is complicated. We want to use everything we know about our students to match them to the right text at the right time, and provide the best scaffolds that will help them to stretch without slipping. pr

Three strategies you can offer students of all levels — even when you can only connect virtually.

What happens when your class is full of 30+ students who have different strengths, different learning styles, and different comfort levels with the English language? We’ve been tackling this question alongside K-12 educators through PD series like Educating ELLs and Including All Learners, where we address the promises and challenges of teaching in heterogeneous classrooms by exploring the principles of differentiation and related research for classroom applications.

When we began another round of Including All Learners sessions last year, we set out to support a new group of educators as they worked toward their differentiation goals. We didn't yet know that we would soon experience social distancing, that toilet paper would become the most coveted household item, or that both teaching and learning would rapidly transition from in-person to online. During this time of online schooling, we are particularly concerned about students who either do not have online access, or do not have a quiet nook in their homes to learn. A few years ago, one of our students commented that he slept with the English novels from our class under his pillow — it was the safest place in his home, where he didn’t have a workspace of his own. As we write this from our individual homes and reflect on the recent shift to virtual education, we are focusing on the principles of our Including All Learners series that remain true in any kind of teaching and learning environment. Below, we will outline a few concepts from our workshops and share how they carry over to our online learning experiences. Disrupt the single story We begin our sessions with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED Talk, The Danger of a Single Story. She explains to her audience how all of us, including Adichie herself, have told a singular version of someone’s life story, and have also been victim to a single story about ourselves. She shares how damaging and incorrect these single versions can be. This concept serves as a reminder that we must disrupt the single stories that are often assigned to our students, particularly those who are ENLs or are students with disabilities. This can be more challenging than it sounds, particularly when students have to be described in IEPs, which do not allow for a more complex telling of their life stories. In our workshops, we challenge ourselves and participating teachers to share other versions of our students’ stories — something you can continue to do in online communication with other adults in your community.

What helps some students can help all

One of the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is that what helps some learners can help all learners. This concept can be illustrated by the design of public spaces — for example, people of all ages and abilities benefit from public bathrooms that are wheelchair accessible; they are wider, are often designed without entry doors, and are therefore easier to navigate and offer fewer opportunities for spreading germs. One way we try to illustrate this concept in our workshops is by providing all participants with tools that support their learning. For example, while we view the Adichie TED Talk, we offer our participants a simple graphic organizer (like a double entry journal) that allows everyone to listen fully, while also allowing them to recall specific compelling moments in the talk. Our double entry journal includes two components: a column on the left, partially filled out with quotes from the text (in this case, the TED Talk), and a column on the right, which is open for viewers to share their thoughts. Returning to the ideas presented in UDL, a double entry journal that includes specific lines from the text is useful for students who have central executive challenges, but in reality, everyone can benefit from the text references. The principles of UDL feel particularly important at a time when it is more difficult to ask students where and how they need support. Just as we provided a partially completed double entry journal for all of our participants, consider making your scaffolds accessible to all students on your online platforms. This might look like providing possible sentence starters to all students for written explanations, or providing a series of clues for students solving a math problem.

Show the messiness of thinking

Metacognition expert Dr. Saundra McGuire defines metacognition as simply thinking about your thinking. Being able to think about how you’re making meaning of a piece of writing — as well what you can easily understand and what you can’t — is an important aspect of engaging with complex texts. One tool we offer educators is a model of a think aloud, where we simply model the messiness of the thinking that goes into making sense of our reading, writing, and problem-solving. The goal is to dispel the idea that a text suddenly and magically makes sense without struggle and hard work, and to show them that everyone relies on thinking moves that help them chip away at difficult texts. Consider doing this type of think aloud with your students online — either in real time or as a short recorded video. Rather than simply creating a video where you explain the major steps needed for answering a question or solving a problem, try to capture yourself actually doing the work, making even your smallest thinking moves visible — the questioning, rereading, reasoning, and revising that often happens while engaging in higher-order tasks, but that we often do without even realizing. You might also share things like how you knew to begin your answer in a certain way, or what bit of information caused you to stop and double-check your computations. Sharing these micro thinking steps will help students see that there is not a singular way to answer a question or to solve a problem, which may help them become more aware of their own thinking.

As you continue adapting your instruction for remote and blended learning, we hope you will utilize the tools and concepts we have outlined here to ensure you are reaching all learners. While our in-person sessions are on hold, you can continue to participate in professional development on this topic by joining us online.

When our lessons are thoughtfully designed and informed by student data, we can provide targeted instruction at every level of technology access.

Differentiating instruction is inherently difficult, and now that we’re doing it at a distance, it can appear even more overwhelming than before. But appearances can be deceiving. Differentiating during this period of distance learning — using some high tech, low tech, and no tech options — can be easy, efficient, and effective!

Differentiation can happen in many ways, with varying levels of complexity. Our Differentiating Like a STAR resource, designed to help educators consider entry points to differentiation, offers strategies in four categories: data, task, text, and grouping. Within each category, we outline three levels of instruction — the more stars included, the stronger the differentiation. By identifying pathways to expand differentiation, you can add depth and complexity to your lessons. When teaching at a distance, we aren’t able to rely on our typical informal observation skills to gather data about our students, including our ability to overhear conversations, see students’ confusion, or listen to their in-the-moment questions. We can, however, find alternative methods for collecting and using data to inform the next steps of our instruction. We use data to inform our instruction at three critical levels:

High-tech: Google Forms

Using the features built into Google Forms, educators can build custom assessments, surveys, pre-, during, and post-reading guides, and much more. When students answer questions within the form, you can be updated instantly. Create a clear connection to the data by turning the form into a quiz. This allows students to receive feedback about their performance, and can allow you to provide instructions for the student’s next task, based on their answers. Students who do well may be ready to move on to a more challenging activity; students who struggle may be directed to re-read or engage in continued practice. When they’re ready, students can return to the quiz to re-test their knowledge and demonstrate their learning. How can you redirect students based on their answers? Use the “go to section based on answer” feature. This feature allows teachers to create hinge-point questions within an online learning experience. Within any multiple choice question, we can establish different follow-up tasks based on a student’s response. If our answer choices are strategic (e.g. 1 correct answer, 1 close answer, 1 opposite answer, and 1 nonsense answer), students can be routed to different follow-up tasks after each question they respond to:

Using these Google Forms features is a great way for educators to create original curricular materials that blend instruction and assessment into a seamless experience for students.

Low-tech: there's an app for that!

Not everyone is up for building a differentiated task from nothing, and that’s okay — there are plenty of existing apps we can use that already have some of the basics set up for us:

These apps and others like them allow teachers to use existing platforms as a way to gather critical data about student performance.

No-tech: phone & paper

Distance learning without immediate and on-demand access to technology is extremely challenging in any circumstance, but especially amid a global health crisis. Students and families who don’t have access to technology are also those most likely to be vulnerable to housing, food, or health insecurity, and it’s in times like these that an equitable education is most at issue. While it might be less fancy, using data to inform your instruction is not less possible when working without on-demand access to technology. Here are a few no-tech solutions that can get us through these difficult times without sacrificing the importance of data-informed instruction:

Whether or not we’re with our students in person, it’s still within our reach to provide targeted instruction. When our lessons are thoughtfully designed and informed by student data, we can offer differentiated instruction at every level of technology access.

|

|

The Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) at Teachers College, Columbia University is committed to making excellent and equitable education accessible worldwide. CPET unites theory and practice to promote transformational change. We design innovative projects, cultivate sustainable partnerships, and conduct research through direct and online services to youth and educators. Grounded in adult learning theories, our six core principles structure our customized approach and expand the capacities of educators around the world.

|

ABOUT US

525 West 120th Street, Box 182 New York, NY 10027 416 Zankel Ph: (212) 678-3161 cpet@tc.edu Our Team Career Opportunities |

RESOURCES

Professional Articles Ready-to-Use Resources Teaching Today Podcast Upcoming PD Opportunities |

COACHING SERVICES

Custom Coaching Global Learning Alliance Literacy Unbound New Teacher Network Student Press Initiative |