|

How the timing of checks for understanding can impact what you learn about student comprehension.

Great teachers want to be sure their students understand content information on a daily basis. They don’t want their students to wrestle with misconceptions, misunderstandings, or mistakes in their thinking that might set them up to struggle as the content unfolds throughout a lesson or unit. As a result, many teachers use small, formative assessments at the beginning, midpoint, or end of a period so students have an opportunity to practice their content and skills, and teachers can assess their understanding at different stages of the learning process. In an effort to ensure that all students have the right answers and a clear understanding of the lesson, many teachers review the correct answers to the assessment before moving on to the next stage of the lesson.

In both examples, we see the teachers making choices that elevate student collaboration, ensuring students have the opportunity to correct misconceptions, connect with one another, and leverage grouping and discussion strategies to process content information. In both examples, the teacher is using a formative assessment — or a check for understanding — with the goal of assessing student comprehension. And in both examples, the check for understanding may be giving teachers more misinformation, than information.

Check for understanding

Well-developed instructional design includes multiple checkpoints to assess student comprehension in real time. Highly effective assessment structures may include between 1-3 checks for understanding in a class period, with each check being an opportunity for students to independently demonstrate their understanding and skills related to the lesson objective or learning target. When we jump from the check for understanding task to the review of direct responses, some unintended consequences may emerge. One likely scenario is that students who had a misunderstanding or a misconception when working on their own will likely copy down the “right answer” during the discussion. But copying down the answer doesn’t necessarily correct their misconceptions. The unintended consequence is that it appears that all the students have the correct answer, even though some may have simply copied down the answer during the discussion. For teachers using formative assessment data to inform their instructional choices, there’s no evidence that helps them know which students had the correct answer at the time of the assessment, which students had an a-ha moment during the discussion, and which are copying down the correct information but are actually still confused. Another unintended consequence is that students discover that the right answers get shared immediately, before their work is completed. It’s a lot easier to copy down the right answers later than it is to work through the hard problem in the moment. Some students may begin to opt out of the learning activity altogether and simply wait for the correct answers. This phenomenon may not be noticeable right away — a gradual disengagement happens slowly over time, and can start with students who appear slow to start, or students who are easily distracted. For teachers feeling the pressure of time, it can be tempting to skip to the right answers even if some students aren’t finished. The challenge is that over time, fewer and fewer students finish the task because everyone is waiting for the right answers to be shared.

Creating space for small changes

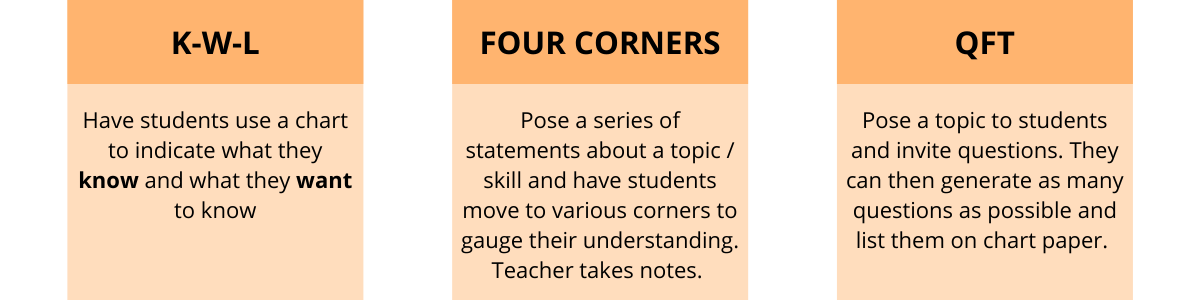

The good news is that there are a few small changes that can make a big difference. Add a reflection. In addition to the discussion of the correct answers, ask students to write a reflection comparing their first response to the correct answer, and share if they made any changes to their thinking or had any a-ha moments in the process. Consider creating a chart on their task that includes space for their individual work, notes from the discussion, and reflection after the discussion. Not only will this provide more insight for you as the teacher, but the students’ metacognition will increase their self-awareness, which supports recall in the future. Have students share & give feedback. The standard share out often includes time for students to work independently, followed by the teacher reviewing the correct answers. This practice can be modified to having students post their answers in small groups at the same time, and then visiting other groups' responses and leaving feedback or asking questions. By turning this process over to students, teachers can increase the responsibility and accountability for students to work with their groups and think critically if different groups have different responses. Leverage differentiation strategies. Building in differentiation as a result of a check for understanding is an effective way of structuring the lesson. Teachers can plan to use hinge point questions, where students receive a specific task as a result of their answer on a check for understanding question, or Four Corners, where students move around the room in real time to show their thinking and discuss with their peers. Both of these strategies leverage real-time responses and interaction to notice misconceptions and work to address them in the moment.

Checks for understanding are a very valuable touchpoint. Getting in the moment information about what is and isn’t clear for students provides insight into differentiation, student grouping, and tweaks to the next day’s lesson. When we reveal the “right” answer before we can gather information on what students know and can do, we might go for weeks before we realize that students have not been learning what they need to be successful on high-stakes assessments like unit tests, projects, or major exams.

It’s true: it is important to correct misconceptions, and we don’t want students to sit in frustration if we’re withholding information that can help them learn. And also, when we jump to reviewing the right answers before we’ve had a moment to collect the data or reflect on how students are processing the information in the lesson, we miss valuable insights that help us plan and prepare the learning pathway for students’ success.

Assess and address students' misunderstandings and misconceptions.

Imagine that you are grading your students’ summative assessments at the end of a unit or grading period. You are feeling extremely confident because your students have seemed engaged the past few weeks. But, as you start grading the seventh or eighth assessment, you realize that there are several questions that assess the same skill or content knowledge that no student has answered correctly. You may start thinking, what’s going on?

In my teaching, I experienced this exact situation. I felt frustrated and disappointed with myself and with my instruction. I thought that my students mastered the material based on their classroom engagement, but their summative assessments revealed otherwise. It led me to ask, how can I better identify and support my students’ needs before the summative assessment? Formative assessments are an excellent, low-stakes way to assess and address students’ misunderstandings or unanswered questions. They can take many forms: short writing prompts, exit tickets, brief video responses, whiteboard questions and answers, conversations, checklists, etc. In any form, they serve as an opportunity to give both teachers and students feedback about progress towards mastery. With that feedback, instruction can be adjusted to better support students’ learning.

Receiving instantaneous feedback

Virtual tools are a great way to ask students focused comprehension questions and to receive almost instantaneous feedback — and many of them are free to use. Socrative is an online classroom app that provides immediate feedback to teachers and students. You can use it to create and assign short, selected-response quizzes or open-response exit-ticket questions. Teachers can see students’ responses as soon as they are entered, and can quickly generate whole-class data. Gimkit is a gamified-way to gauge students’ comprehension. Students answer selected-response questions at their own pace, earn imaginary coins, and shop for powerups and game features. Games can be set to last for a set amount of time, which makes it an easy addition to any lesson plan. Plus, students love the gaming interface! Google Forms, which is integrated within Google Suites, allows you to adjust the settings of a Google Form and turn on the “make this a quiz” function. This will allow you to make an answer key for selected-response questions and to add points and automatic feedback to students. You can see automatic summaries for all quiz responses, including frequently missed questions, graphs marked with correct answers, and average, median, and range of scores.

Gathering invaluable student data

If you're looking for an alternative to digital tools, exit slips are a great way to gather information about students’ current understandings and/or questions. On a piece of paper or a document, ask students to respond to 1-3 questions that ask them to recall or apply information at the end of a lesson. Student-led conferences, including conferences between student/parent, student/teacher, or among student/parent/teacher allow students to highlight significant areas of growth and to set goals for future learning. Ask a student to bring a sample of their recent work — it could be a summative assessment, a written piece, or a collection of classwork. Then, ask students to reflect on how these learning artifacts reflect their progress in certain skill areas. These conferences can be student, teacher, or parent initiated. Color-coded student reflection can be a great way for students to reflect on the progress of their own learning towards a goal. When a student goes to turn in their practice work, ask them to highlight their name on the paper using a color-coded system: red to signify “I completely understand and could teach someone else this skill,” blue to signify “I think I understand, but need some more practice,” and green to signify “I don’t think I understand yet and may need some more support.” Keep the highlighters next to your turn-in bin for student work. For younger students, this can also be a great practice to remind them to write their names on their papers.

Thoughtful assessment practices

Listen and respond: whenever you give students a formative assessment, make sure to respond to students’ strengths and opportunities for growth. If a formative assessment only gets graded and handed back without an adjustment in instruction, that is a lost opportunity to provide student-specific and class-wide support. Keep it brief: formative assessments don’t need to be long or multi-tasked. They are often most effective when they target one specific skill or piece of content, especially when there is room for misunderstandings. Experienced teachers often know when and where students may get tripped up and can plan formative assessments accordingly. Encourage students’ self-reflection: use formative assessments as a metacognitive practice to get students thinking about their own thinking and learning. It can be great for a teacher to identify and offer support for a student’s misunderstandings, but it can be even better for a student to take that initiative for themselves.

Formative assessments are powerful tools for both teachers and students to reflect on the process of learning. Remember, they can take many forms and can still provide valuable insight into students’ progress towards mastery. Ultimately, formative assessments can help to shine a light on misunderstandings and misconceptions so that, as educators, we can offer necessary help and support to our students.

Understanding the connection between what is taught and what is learned is a vital part of your classroom practice.

One effective tool we use when delving into new content is the resource It says...I say...So... With this tool as our guide, we can explore Danielson’s Framework for Teaching, 3d Using Assessment in Instruction.

Danielson 3d says...

“Assessment of student learning plays an important new role in teaching: no longer signaling the end of instruction, it is now recognized to be an integral part of instruction. While assessment of learning has always been and will continue to be an important aspect of teaching (it’s important for teachers to know whether students have learned what teachers intend), assessment for learning has increasingly come to play an important role in classroom practice. And in order to assess student learning for the purposes of instruction, teachers must have a “finger on the pulse” of a lesson, monitoring student understanding and, where feedback is appropriate, offering it to students.”

This means...

This looks like...

This is challenging, because...

So...

Let’s consider formative assessments. They are most helpful to us when making instructional decisions. They are used to monitor student learning and inform feedback. They help give us an overall picture of a child’s achievement. Formative assessments are used throughout the lesson.

You can try...

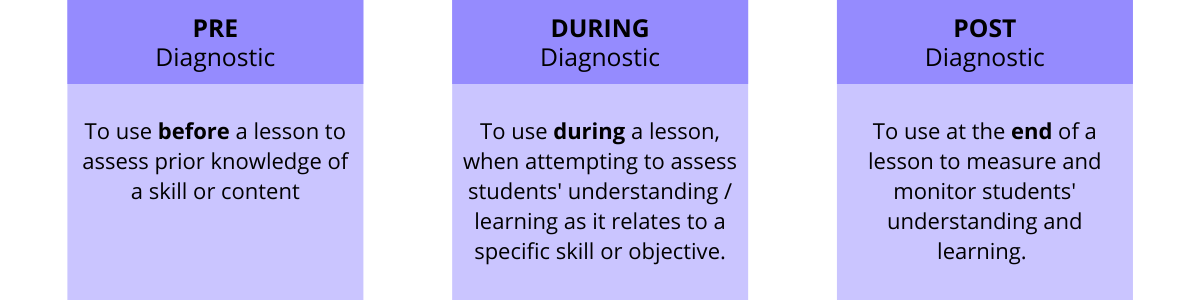

Below are a few examples of practical pre-instruction assessments you can try in your classroom.

What are you trying in your classroom? What do you want to integrate into your practice? Tell us more in the comments! Learn more about opportunities to Design Coherent Instruction for your students.

Equitable practices empower students to recognize and develop their own talents and skills, and become agents of change for their futures.

What is equity? How do we define and use it in education?

Whenever there is a buzzword at play in education circles, we like to unpack, define, and interpret how the term applies to educators and schools. Let’s start with the difference between equity and equality. A simple, working understanding of equity involves “trying to understand and offer people what they need to enjoy full, healthy lives." In education, equity means truly striving to achieve the best possible outcome for each individual student. Equality, in contrast, aims to ensure that everyone is offered the same things in order to enjoy full, healthy lives. As educators, the notion of offering all people the same things immediately contradicts our understandings of differentiation. We know that not all students have the same needs. Furthermore, students from underserved backgrounds, generally low-income or students of color, may benefit from a variety of resources to succeed academically. All students benefit from equitable practices. I’d like to suggest that we not only offer students additional opportunities or resources to “catch up” or to “level the playing field”, but instead create a new playing field in education. We can start with our own assessment policies and systems in our classrooms, departments, schools, and districts. Creating equitable education and assessment practices doesn’t end with offering students what they need or deserve to succeed. Equitable policies and practices aim to empower students to recognize and develop their own talents and skills; to become agents of change for their futures. Equity means achieving lasting results for all people, regardless of their socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic backgrounds.

Examining our assessment practices

Equity work in any context may require seeing differently, thinking differently, and even working differently. Therefore, it may be helpful to start by asking ourselves some probing questions about our own assessment practices and beliefs. Consider discussing these questions at your next faculty meeting to norm understandings around assessments, or answering them individually, as a way to understand your own beliefs.

Creating equitable assessments

To work toward equity in education and in assessment, let’s examine our assumptions about educational achievement and assessment. Ibram X. Kendi, author of How to Be an Anti-Racist, explains how traditional testing policies perpetuate racist (and inequitable) ideas and policies in education. He explains that “achievement in this country is based on test scores, and since white and Asian students get higher test scores on average than their black and Latinx peers, they are considered to be achieving on a higher level.” We may not have the power to single-handedly change high-stakes testing policies that use assessment scores to measure educational achievement, but we do have influence over our curricular decisions and how we assess and grade our students. We can create more equitable curricula and assessment practices and policies to create more equitable education. To do this, we must:

Assess what we teach & teach what we assess

There are some basic rules of thumb that we can use to create a more equitable foundation for assessing students. As a starting point, we can simply ensure that we assess what we teach and teach what we assess. Backwards design, from Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe’s Understanding by Design model, offers a framing to ensure that we first plan our assessments — including all the key teaching points and skills needed for them — as a guide to our instruction. Next, we “backwards plan” our units and lessons to ensure that we are meeting each of our teaching goals as we work our way toward the end of unit assessment. In addition to planning for end of unit assessments, we can also plan our formative assessments, which will help us understand students’ mastery of each discrete skill throughout our lessons. This will also create space to reteach concepts as needed, as well as ensure that we are offering students a range of possible opportunities to learn throughout a unit. When formative assessments reveal or confirm for us which students are struggling or need to revisit a concept or skill, we can differentiate how we reteach or review. If the teaching didn’t stick as we’d hoped the first time around, why would we teach it again in the same way? These practices can help us take initial steps toward ensuring our students are offered fair assessment opportunities, and we can build equity from there.

Differentiating assessments

Traditional assumptions about assessment may lead us to believe that asking students to complete different assessment tasks to demonstrate mastery may not feel fair — but it may actually be more equitable. I admit that early in my teaching career, the concept of differentiated assessments took me a while to grasp and to actually believe in. Many of us use differentiation expert Carol Ann Tomlinson’s helpful framework to guide our daily planning and instruction. We plan differentiated processes using a variety of scaffolds, tools, extensions, student groupings, pacing and modalities. We differentiate content in the form of offering or using a variety of “levels” of texts, math problems, and complexity of tasks. We strive to create a supportive and differentiated learning environment to meet a variety of students’ needs. But, when it comes to differentiating products or assessments, it is a little more complicated. Here are a few simple ways to differentiate assessment products to create equity:

Make assessments rigorous, not rote

Research shows that, especially in marginalized or lower income neighborhoods, lessons for students often focus on rote skills and procedures. Often, this means that students are not expected to achieve, nor learn more rigorous skills and content, when compared with their peers in higher income communities. As we know, rote and procedural learning tends to be boring, and when learning is boring, we often disengage or act out. This may become a serious equity issue in marginalized communities, especially for students of color, where, when students opt out of learning or act out, they may face harsh (or criminalized) punishment. Either way, students lose. Instead of focusing assessments on acquisition or mastery of rote skills or procedures, we can aim to emphasize reasoning and problem-solving skills. Research consistently proves that opportunities for supported, productive struggle can motivate students to stick with a task and to stay engaged as they learn. We all do better when we can engage in productive challenges.

Make assessments relevant

Culturally relevant curriculum and instruction create more equitable education for all students. Zaretta Hammond, in her wonderful book Culturally Responsive Teaching & the Brain, defines culturally responsive teaching as “encompassing the social-emotional, relational, and cognitive aspects of teaching culturally and linguistically diverse students.” She believes that when we teach with these concepts as our guiding lights, we create more equitable education. Similarly, we can create more equitable assessment practices if we offer students experiences that are adapted for their cultural and linguistic diversity and are cognitively appropriate and engaging. Here are a few simple ways to make assessments more culturally relevant or responsive:

Develop and maintain a growth mindset

We often think about how important it is for students to develop a growth mindset, yet, as educators, we need to take a hard look at our own biases and assumptions that things may be “too hard” for students. As Carol Dweck points out in the The Power of Yet, with scaffolding and high engagement tasks, we may find that students surprise us and we can reframe our thinking to become, “they don't get it yet.” Many factors contribute to a student’s mindset and development of a learner’s stance, especially a teacher's language and perspective. Here are a few simple ways to support a growth mindset for assessment practices:

Cultivating strengths and talents

As educators, our job is to cultivate students’ strengths, as well as help them develop in areas of struggle. All students benefit when teachers recognize and cultivate their passions, talents, and skills. Students also benefit when teachers recognize that a class or subject is an area where they need some extra support and that simply making progress is an achievement, even if their skills have not met or exceeded standards. When students are not achieving in a particular subject area, it may be time to think differently about how we assess them. It is possibly a waste of talent and potential if we expect students to spend academic time and energy striving to achieve in an area that continues to be a struggle for them. Instead, we can think more holistically about each student, in an effort to balance supporting improvement in areas of challenge with sponsoring soaring success in areas of strength. We can continue to cultivate and encourage a student’s passions and talents, even when assessing them. Measuring and recognizing ongoing progress and effort are important components of assessing a student’s learning.

Many of us were educated within systems that housed traditional or standardized assessment and grading systems. As educators, we have all consciously or unconsciously based a grading policy or assessment practices on the modeling we learned as students. It can take a leap of faith to imagine new and innovative assessment practices — but we must rethink our notions of fairness and begin to think about developing practices that are equitable for the students in our care.

Resetting instructional priorities in the absence of high-stakes tests.

Across the US, state tests are high-stakes exams that have become a driving force in educational policy, funding, accountability, curriculum development, and achievement for students, teachers, and school leaders.

No Child Left Behind and its counterpart, Race to the Top, were the national policies that dominated education spaces and shifted the focus from school and district autonomy to a culture of testing. While the Every Student Succeeds Act lessened some of the federal mandates on state testing programs, some individual states, like New York, have redoubled their efforts to use high-stakes assessment data as a way to evaluate education at every level. That is, until 2020 when COVID-19 systematically closed schools, reshaped instruction into hyper-customized blends of in-person and remote learning systems, and fundamentally prevented large groups of students from sitting in the same place, at the same time, to take a paper and pencil, fill-in-the-bubble test, like the generations of students who came before them. This might sound like an exaggeration, but it isn’t — in its 200-year history, 2020 was the first year in which state tests were canceled. Now that schools around the country are coming back in person almost exclusively, we're looking at a school year that will formally assess student performance for accountability for the first time in almost three years.

What will you teach?

For the past twenty years, rigorous high-stakes state tests have become the leading influence on curriculum development and instructional priorities for most public schools. These structures for accountability send a direct message to educators — the only knowledge that is important is the knowledge that aligns with the test. State tests are directly connected to the following evaluation and accountability processes:

Traditionally, almost the entire schooling experience, at every entry point, is connected to a test which reviews, monitors, and evaluates performance. Many schools have used this mandated external guidance as a way to vet their curriculum, solidify their unit and lesson plans, set the plan and pace for their instruction, and set specific goals for students. While, “you need to know this for the test” isn’t always a compelling reason for students to become interested in a specific topic, it has certainly been a driving force for teachers in the past. But without the guidance provided by the test, many educators were free to ask, what should I teach? After getting over the initial shock of the tests’ absence, many teachers developed thoughtful, dynamic, and innovative curriculums to capture their students’ interest in the content, even while learning through difficult times. As the exams come back into focus, are we at risk of losing this personalized curriculum in order to return to the kill and drill of test-driven instruction?

Shifting your approach

What should we be teaching, and who should decide? After two decades of test-informed planning and two years of freedom from exams, how do we decide on our next steps? It is my hope that we can use this as an opportunity to take an honest look at who gets to set the agenda for learning, and in doing so, acknowledge the reality that while oversight is absolutely necessary in education, high-stakes testing is limited, and limiting. We have to be able to move from simply valuing the test, to testing what we value in each subject area — and teachers and local school communities should have a say in what that looks like. Even as testing returns, there are three approaches to unit planning that we can use to frame instruction that is relevant, personalized to students' interests, and prepares them for future exams.

Considerations for policy makers

To our partners and colleagues who are decision-makers — big and small — we know you have a bird's-eye view of the now and the next. While we’re waiting, consider (or possibly reconsider) the enormous weight we’ve placed on a single day exam. Current policies give the test a monopoly on setting the values for an entire generation of students, and silence the voices of classroom teachers and school leaders who work directly with students on a daily basis. These educators have insight into what we could be valuing across fields, and how student progress and performance can be reflected to increase student achievement. We have a rare, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to rethink the role of high-stakes tests and shift the structure of accountability to one that incorporates true multiple measures, embraces diverse learning needs, and reflects the population of students we’re serving.

Reflecting on our values and focusing our instruction on what will help students get engaged, stay engaged, and keep coming back day after day is where we should invest our time and energy. After what we've been through, our instruction should look different than it did before. We have a unique opportunity to apply our new skills, refine what we've designed, and return to “normal” a bit more evolved than when the pandemic began.

Reading and responding to students' work is a necessary step in meeting their needs.

I have been an educator for over twenty years, but I can still remember being a first-year teacher and asking my students to pair read Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery. I was nervous, and anticipated comments like, “Miss, aren’t we too old to read aloud? And in pairs? That’s little kid stuff.” But after I modeled the process with another teacher, I broke my students off into pairs and, within minutes, my ninth grade students were reading with one another. Students plopped themselves throughout my classroom, on the floor and at desks, and were taking turns reading aloud and talking to each other. I glanced around the room in amazement at the pairs reading softly, talking, giggling a bit, looking at each other, looking at their books. This is what school should look like, I thought to myself. This is what learning looks like. This is what working together looks like. I felt tears well up in my eyes witnessing reading as a social activity, and was never more certain of my career choice.

This moment embodies what I love about teaching. But anyone who teaches will tell you that this moment represents a mere slice of teaching life. Teaching is also grading papers, homework, projects, and everything in between. And at the end of each term, every student needs to have a grade next to their name. What plagues so many of us is how to grade students as fairly as possible — how can we assess students frequently enough to give them multiple opportunities to demonstrate their learning, and to inform our lesson planning?

Grading efficiently

This assessment dilemma is real for me. In addition to my work at CPET and as a literacy consultant, I am also an adjunct professor, and my roster this term has doubled in size. I know how important it is to use formative assessments in my classroom — James Popham says it best: “Formative assessment works!” — but the only way formative assessment really works is when the teacher efficiently grades and provides feedback in a timely manner. Nobody sets out to be that teacher who students refer to as "the one who never gives anything back" (cue student eye roll). I reached out to my colleagues at CPET for advice on how to grade formative assessments effectively and efficiently, and will share with you some of their pragmatic tips:

While I may not love grading papers as much as I love watching my students read to each other or interact with one another as curious learners, I know that assessments matter to my students, and they guide my lesson designs. Reading our students’ work is an effective step in meeting their needs.

What methods have worked well for you? We’d love to hear the ways in which you’re effectively managing your time and assessments — comment below or tag us online @tccpet!

Opportunities for micro assessments that ensure students are developing the skills needed to overcome academic obstacles.

We often think about learning like a marathon, as if it's this long, long race where everyone begins at the same starting line, sets their pace, and runs at that pace for a long time until they arrive at the finish line. But there’s a problem with this analogy. The problem is that learning does not typically happen in consistent, incremental stages. Instead, learning happens in fits and starts, and in the best situations, it is the result of being deeply curious about a subject, topic, or theme and engaging in a productive intellectual challenge. In fact, when we really get down to it, learning isn’t like running a marathon at all! If learning is like running, then it’s probably a lot more like jumping hurdles.

When jumping hurdles, runners begin at the starting line and then sprint as fast as they can towards the first obstacle they have to overcome. If they’re successful, they continue to sprint forward. If they are not successful, the hurdle falls down, or worse — they fall down. Then they have to pick themselves back up and start again. Runners who can overcome all of the hurdles sprint through each stage on the track. Runners who cannot fall behind abruptly, and sometimes, permanently. To train runners in hurdles, coaches help them practice by providing a set of smaller obstacles along the track, and train them through practice sessions where they develop specific strategies that will refine their skills. Coaches watch the moves the runners make while they’re jumping, and study these moves to give the runners actionable feedback about ways they can adjust their footing, their stance, and their speed — all of which help them to become better at the sport. This is the same kind of training and support that checks for understanding provide for students.

Micro assessments

Checks for understanding are micro assessments that teachers can build into their lessons to ensure that students are developing the strength, skills, and strategies necessary to overcome the academic obstacles that will be presented in a long-term project, assessment, or high-stakes test. They are mini-hurdles that can help a teacher determine which students are sprinting ahead, which have minor gaps in understanding, and which are struggling to make sense of the lesson content or skills. Traditional instruction organizes the procedure of a lesson so that the teacher presents on the important topic of the day, the students engage in practice related to that topic, and then go home. Everyone holds their breath and hopes that the students do well on the quiz at the end of the week. In our analogy, this model would be equivalent to a coach turning away from a race, hoping their runner is able to finish. Students, like runners, need three things from their teachers to increase their speed, strength, flexibility, and stamina. 1. Tasks that gradually increase in difficulty Like a coach who lays out smaller hurdles on the track to teach runners about basic techniques, teachers can provide short tasks for students at strategic points in a lesson. One simple structure for a lesson would be to include one check at the beginning of the lesson, one in the middle, and one at the end of the class period. The opening check serves as a baseline understanding of what students remember from a previous lesson, and assesses their prior knowledge or current thinking about a topic. The mid-lesson check becomes a moment to micro-assess their understanding of the essential learning of the lesson. What must students understand in order to meet the learning target or objective? Finally, an end of lesson check gives us vital information about how students are leaving the class. This check informs our instruction for the next day’s lesson. 2. Actionable feedback for micro adjustments We often assume that assessments always equal grades. But just like not all runs are races, not all tasks need to come with the heavy weight of a graded assignment. Small and simple assessments designed as checks for understanding provide key insights into students’ knowledge while it’s in formation. This is critical to helping teachers understand how students are making meaning, as well as how they’re interpreting (or misinterpreting) the content. Rather than focusing on how many points to provide, consider ways of providing students with actionable feedback that includes micro adjustments. Micro adjustments may include offering students a suggested next step, pointing out something they did well, or giving a tip as to what would have made their response more complete. The goal is to move away from evaluative feedback like “good job” or “needs work” and move into actionable feedback, which gives students a concrete next step to practice. When we get good at building checks for understanding into our lessons, we can design our lesson sequence to build on the feedback we give students in the moment. 3. Celebration of progress As many runners can attest, marking personal progress is critical to building confidence even when someone else crosses the finish line first. As educators, it is essential that we are able to note specific areas of improvement for students at all levels. We can make connections between their gains and future successes, which increases their investment in their learning and can help them to set short- and long-term goals.

Getting started

There is no shortage of strategies for checks for understanding. Below is an example of one of our favorite sequences using US Government as an example topic.

There are countless ways to monitor our students’ learning. When we are engaging in beginning, middle, and end of lesson checks for understanding, we have so many opportunities to notice our students’ process and progress, to reflect with them, to encourage them, and to help them leap over the obstacles they encounter on their learning journey.

Exit tickets allow you to breathe for a couple of minutes before your next class period starts.

An exit ticket is like an Instant Pot. You hear about how great it is — it saves time, it’s simple, it’s flexible, and it doesn’t need many ingredients. It seems to be a staple tool at this point, so you pick one up and start using it. So it goes with exit tickets. When we start using them, it may be because of both convenience and necessity. They’re quick and easy, and they allow you to breathe for a couple of minutes before your next class period starts or you need to switch over to the next subject you’re teaching.

Exit tickets also provide a supportive rhythm to your class. They signal to kids that they will be transitioning soon, and this is invaluable to many students — especially if they struggle with change during their school day. Exit tickets provide a natural way to move from one space into the next, figuratively (if students stay in the same classroom) and literally (if students move to a new room). Sometimes that’s as far as we get with using exit tickets. It feels like enough, especially at the start of the school year or in the first year of your teaching career. But we can improve our use of exit tickets by taking them from simple (and valuable!) classroom tools and morphing them into invaluable formative assessments. “The power of exit tickets lies not only in informing instructional decisions — it includes the public acknowledgment of students' ideas and making adaptations of lessons, based on these responses, transparent to students (Marshall 2018). Importantly, exit tickets can also give voice to students who are otherwise silent in class, including English language learners and students "on the margins" of classroom life, and can draw your attention to who is being served in which ways, giving you critical information for shaping your practice to enhance equity and inclusivity.”

What is an exit ticket?

Backing up for a minute, let’s define an exit ticket. An exit ticket is a task that typically requires a short response from students. Teachers use exit tickets after an activity or learning period, and it can literally be the ticket to exit the room at the end of a period or a way for students to exit a part of the lesson. Exit tickets are not graded. Because they are not associated with a grade, students take on very little risk and can be honest about what they do and don’t understand, and may be more likely to ask questions they wouldn’t on a graded piece of writing.

Using exit tickets as formative assessments

Exit tickets can be used in any subject area at any grade level as formative assessments to provide teachers with authentic data, in real time. “To be effective, an exit ticket should have specific prompts for students and take only about five minutes to complete. Students can record their responses on index cards, sticky notes, notebook paper, or online (e.g., Google Forms, Padlet, Schoology, etc.). Ideally, student responses inform the next stages of learning by highlighting whether teachers should clarify ideas, reteach them, extend them, offer practice, introduce new ideas, or restructure future instructional activities (Marshall 2018).”

Making exit tickets your own means designing (or using templates) for short responses that you can read fairly quickly. This can be as simple as a sticky note on which students respond to a prompt with a few words or a What, So What, Now What chart.

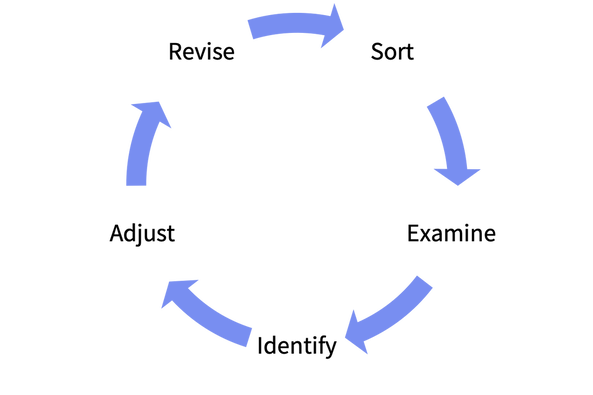

At the end of a day, class period, or activity, you can engage in a quick cycle of inquiry with the data.

1. Sort the data based on your own criteria from the lesson or for your specific students.

2. Examine each set of data. What do you notice? What needs attention?

3. Identify areas that need to be taught, retaught, or further investigated.

4. Adjust your next lesson to accommodate your findings.

5. Revise your next exit ticket (if needed) if you see that your prompt isn’t yielding useful data.

Using exit tickets as formative assessments is a promising practice that can be quick and can also support deep and differentiated learning in your classroom. Share with us your exit ticket practice below. Similar to Instant Pots, when you learn new ways to use them, it’s fun to share your findings with others!

|

|

The Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) at Teachers College, Columbia University is committed to making excellent and equitable education accessible worldwide. CPET unites theory and practice to promote transformational change. We design innovative projects, cultivate sustainable partnerships, and conduct research through direct and online services to youth and educators. Grounded in adult learning theories, our six core principles structure our customized approach and expand the capacities of educators around the world.

|

ABOUT US

525 West 120th Street, Box 182 New York, NY 10027 416 Zankel Ph: (212) 678-3161 [email protected] Our Team Career Opportunities |

RESOURCES

Professional Articles Ready-to-Use Resources Teaching Today Podcast Upcoming PD Opportunities |

COACHING SERVICES

Custom Coaching Global Learning Alliance Literacy Unbound New Teacher Network Student Press Initiative |