|

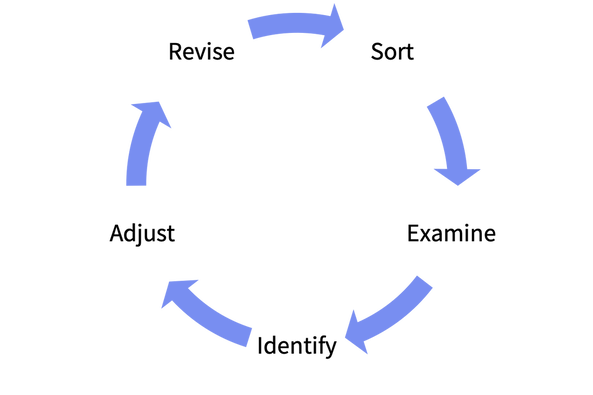

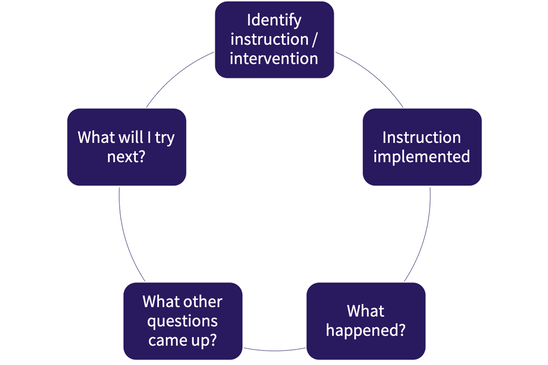

Navigate a four-part cycle that will help you develop effective assessments and determine students' needs.

Adapted by G. Faith Little from CPET’s Handbook: Design Your Own ELA Assessments, by Courtney Brown and Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang.

As educators, we assess our students in multiple ways for many purposes: to evaluate what they know and can do based on the skills and content that we teach them, to make instructional decisions, and to reflect on teacher practice. Quizzes, in-class activities, homework, and writing assignments are all opportunities to find out how our students are achieving. By analyzing and interpreting the results of these tasks, we can determine the needs of students and adjust our teaching to help students succeed.

Periodic assessments are low-stake assessments designed to provide timely and detailed information on students’ strengths and weaknesses, as well as their progress over time. The results from the assessments are used by teachers as data to inform instruction. They can also be used to start and deepen communication with parents / caregivers who can support their students’ learning outside of the classroom.

Establishing learning goals

The assessment and rubric development cycle begins by establishing learning goals. Wiggins and McTighe (2005) pose these helpful questions: "What content is worthy of understanding? What enduring understandings are desired?" Addressing these questions will help teachers establish learning goals for the entire year, as well as individual units. Periodic assessments should be designed to measure students’ progress in these learning goals and relate directly to the content of teachers’ instruction, i.e., books, plays, stories, etc. These goals, in ELA, for example, should relate to the reading process, knowledge of literary conventions, making meaning (analysis), and communicating in writing. When teachers develop learning goals together, there is cohesion and focus in how the school supports students’ learning. In any content area, learning goals specify the crucial understanding teachers expect students to develop and the key skills or competencies students should demonstrate. Learning goals for periodic assessments can be developed by teachers, often working together within a school, and referencing important resources, including state mandated learning standards and performance indicators, schoolwide learning standards, disciplinary criteria, and teachers’ own expectations for student performance. Articulate learning goals by answering the following:

Ready to begin mapping our your goals? Download our Learning Goals worksheet.

Developing assessments and rubrics

Assessments Formative assessments are those that focus on the students’ performance as they develop important knowledge and skills — they’re meant as benchmarks or milestones along the journey rather than the final destination. Teachers can use the data from these assessments to determine future instruction. Periodic assessments should be aligned with student performance standards, learning goals, and the curriculum in each unique learning community. While each assessment (Fall, Winter, and Spring) may look different, designers should carefully consider how the assessments measure students’ growth throughout the entire year. These assessments will provide valuable feedback for teachers to improve instruction, align to standards, and measure student growth. These curriculum-embedded assessments have great potential to inform teachers and schools of the students’ progress toward established standards. Curriculum-embedded means an assessment is designed to reflect the actual curriculum being taught in the class. This is in contrast to most standardized tests, which generally do not pertain to the curriculum taught in individual classrooms. The chosen approach often influences the type of data accumulated. Aligned assessments

Description

Each assessment maintains the same format and requirements. Many teachers have used similar persuasive writing prompts with the same requirements for each assessment. This approach allows for consistency and assessment routines. Data information Since each assessment is very similar, teachers are looking to see students’ scores increase on each assessment. Longitudinal score results are reliable because the assessments are similar and the same rubric is used for each one. Teachers can identify areas where scores do not increase as areas in need of additional instruction. Progressive assessments

Description

The assessments become progressively more difficult, to reflect the growing knowledge and abilities of students. The assessments are designed to reflect the latest content unit as well as yearlong learning goals. This approach allows for flexibility and takes a snapshot of student learning. Data information Since each assessment gets progressively harder, maintaining scores indicates students are learning and growing. Score results directly reflect the most recent instruction and show what information students did not fully grasp. Teachers can make determinations about what should be reviewed or revisited from a new approach. Project-based assessments

Description

The assessments are inextricably connected to the classroom units and allow for students to express learning in multiple forms. Project-based assessments are designed to reflect the latest content knowledge through authentic (real-world) projects. Data information Since many of these authentic assessments include a publication or performance, an early draft of the project may be used as the assessment because it represents the students’ own work without additional assistance. Teachers see scores as reflective of “live knowledge” and immediately use the data to identify important lesson topics and share feedback with students so they can revise. Responsive assessments

Description

The assessments are designed to measure growth in specific areas, based on information learned by analyzing the data and student work. Responsive assessments attend to the needs presented by the students and they inform specific areas where instruction should be elaborated. Data information Since these assessments are designed as a response to the data, the support structures in each assessment may increase or decrease, depending on the time of year. Areas where students are scoring poorly may indicate that increased support is necessary for the next assessment. When analyzing the data, teachers are primarily interested in how students are performing in these specified areas where they’ve made changes in an effort to increase student performance. Rubrics The rubric, a scoring guide that uses descriptors for every performance level, is an essential component to any assessment. While rubrics may come in many shapes and sizes, the most effective rubrics are those that encapsulate the focus dimensions of the assessment and clearly describe the strengths of the performance at every level. Rubrics are most effective when they are assessment-specific because they are created for the precise task and requirements of the assessment, unlike all-purpose rubrics, which are often broad or ambiguous to account for a wide variety of assessments. The following ten criteria (adapted by Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang from the work of Dennie Palmer Wolf of the Rethinking Accountability Initiative at the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University) mark the foundations for creating an effective rubric that reliably evaluates student work:

Frequent pitfalls of rubric design

Too much / too little information Too much information and the rubric bleeds on to too many pages, the expectations are barely read, and it can be difficult to use. Too little information leaves too many qualities of the assessment undefined, and therefore, difficult to score. Consider aiming for 3-6 dimensions and performance levels with 3-5 consistent qualifying statements for each. Vague, ambiguous, confusing or contradictory language Consider using descriptions that clearly explain what the student did. Professional or exclusive language vs. inclusive language Be careful not to exclude students from understanding the rubric by using ultra-sophisticated or academic language. The most popular buzzwords don’t always make the best rubric descriptors. Use student-friendly language that capitalizes on words and phrases commonly used in the classroom. Expectations for assessment misaligned with the rubric Be sure to align the rubric with the learning goals and the assessment. It’s crucial that designers pay close attention to the assessment requirements and the rubric language because if something is not on the rubric, it cannot be used as a factor for evaluation. Scoring is inconsistent with performance levels If scores seem inconsistent with the performance levels (for example, a student earned “Proficient” but only earns a score of 2 or 65%) it may be necessary to revise how the scores were assigned to each level. Consider testing the rubric scoring system to be sure numeric scores or percentages are accurate to their performance level.

Designing assessments & rubrics is important and challenging work. Partner with CPET to create customized materials and support successful implementation of effective tasks, assessments, and rubrics!

Scoring assessments

All assessments must be scored in order to produce the data used to inform instruction. When scoring assessments, we recommend that schools use a team approach, which may include both teachers from the specific content area and teachers from other disciplines. This promotes school-wide collaboration, builds community, and supports reading and writing across the disciplines. Team members should prepare to score by taking part in a “norming” process, reviewing and discussing the task to clarify what the students are asked to do and what teachers expect to see in their work and become familiar with the rubric. Next, it is useful to have a “norming discussion”: everybody reads and discusses several samples of student work from the assessment task, each teacher scores the work individually, and then group members share scores and discuss how they used the rubric to score the student work samples using evidence from the papers to justify their scoring. Once teachers feel comfortable with using the rubric, teachers should score the students’ work from the assessment. We suggest building in a “reliability check” process to make sure that the students’ work is being scored fairly and consistently so that the data will be reliable. Periodic assessments are most useful when scored as soon after the administration of the assessment as possible, so the data is relevant and timely. The longer the gap between students’ taking the assessment and the data report, the less useful in informing instruction the data will seem to teachers and administrators. SAMPLE: An approach to collaborative scoring

Two important common principles: (5-10 minutes)

Clarifying the task (20 min)

Norming (30 - 45 min) Distribution of copies of assessment #1

Scoring (duration depends on task content / length) First Scoring

Score comparison (duration depends on how scores match up)

Mediation (if necessary)

All assessments with final scores should be returned to facilitators. Woohoo! We did it!

Analyzing data

Data comes in many forms and is used every day by teachers to help plan instruction and adjust our teaching. Quizzes, essays, homework, standardized tests, and attendance records are all data. Teachers’ observations of students at work are also an important form of data. Students’ responses and behavior are data. No one form of data will give a complete picture of a student’s achievement. There is no shortage of usable data; however, it is how we collect and analyze the data wisely to inform teaching and learning that matters. This step in the cycle specifies a systematic process, one that allows us to look closely and analyze the data. A careful analysis of the data will yield important information about our students’ strengths and weaknesses. Based on this information, schools and teachers can develop or revise learning goals, and teachers can plan specific instruction for a class and/or individual students to best address students’ needs. We suggest that data discussions be carried out among specific content area teachers and with colleagues from other disciplines. This will allow teachers across the curriculum to identify and address students’ needs — for example, organizing an argument in writing, using evidence to support their thesis, articulating rationale for a solution to a problem or a hypothesis, etc. Data is any form of information collected together for reference and analysis. Another way to understand data is as evidence of desired results. In the case of periodic assessment data, scores from student work provide data for understanding how students are performing related to specific learning goals. This is where curriculum-embedded assessments can be most powerful. You actually have to anticipate the kinds of data that will be useful as part of developing a unit of study. The data may be used to answer questions about whole class performance and individual student performance. The data reports will also help teachers to adjust instructional strategies to address students’ needs — e.g., what might need to be retaught or taught differently?

Ready to communicate with a student about their strengths and goals? Download our Individual Plan for Improvement Sample to use when sharing data with students.

Continuing the cycle

Assessing students is most valuable as part of a cycle that begins with establishing student learning goals and involves developing curriculum-embedded assessments and rubrics, administering the assessments, scoring them, and analyzing the data they produce to inform instruction. Keep the cycle going from baseline to end of year assessments! 10/31/2022 Centering Students for Literacy Engagement: Teacher as Interdependent Curator & Bridge-Builder

Exploring the connection between instructional autonomy and student engagement.

Excerpted from Centering Students for Literacy Engagement: Voice, Choice & Identity, A Review of Literature for Behind the Book, conducted by the Center for Professional Education of Teachers at Teachers College, Columbia University.

Teachers who engage in the design of their own instructional goals understand the direct link between engagement, literacy, and content knowledge. They understand that when students are engaged, there is no limit to their learning, which is why it is such a powerful motivator. Teachers are also keenly aware that how they create visible and invisible space for learning to take place has an impact on student engagement. Everything from how a classroom space is organized, decorated, and maintained has an impact on how well students can physically interact in the space. Relationship building is also critical in the classroom, and the research indicates that fostering non-evaluative literacy experiences creates opportunities for students and teachers to more deeply engage in reading and writing.

Essential factors in engagement

In a research review on literacy engagement, produced by The Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) in collaboration with Behind the Book, we analyzed previously published reviews of literature and research studies on literacy engagement. Throughout the literature, student voice, agency, and confidence emerged as essential factors that lead to increased literacy engagement over time. While many attributes contributed to increasing student voice, choice, and agency, six high leverage areas surfaced: student voice, student agency, student confidence, teacher autonomy, learning environment, and relationship-building. Refer to our companion article to read about Student Voice, Choice & Identity. How do you incorporate these in your practice? What support might you need to deepen your understanding and implementation of these attributes?

Teacher autonomy

Decision-making ideally involves all stakeholders in a school community. The unique role of teachers positions them as professionals in their content areas and the consummate experts of their own classrooms. There is a strong connection between student engagement and how a teacher perceives themselves as authors of their classroom spaces — especially when it comes to teacher autonomy. The concept of professional independence and decision-making is central to motivating teachers to think critically about what, why, and how they’re engaging with their students, which increases their sense of personal and professional responsibility. Teachers navigate their choices within the systems and structures of their districts, school, and department. Educational policies affect the everyday experience of teachers and can construct barriers to teachers exercising autonomy in their classrooms. The shift away from autonomy and professional freedom in K-12 schools has had a dramatic impact on teacher engagement, creativity, and organic professional evolution. Policies that acknowledge teachers as experts will implement systems and structures designed to increase decision-making opportunities on every level, from classroom to school to district. Teachers immersed in the design of their own instructional goals understand the direct link between engagement, literacy, and content knowledge. They understand that when students are engaged, there is no limit to their learning, which is powerful for both teacher and student. When a person has a high level of efficacy in their work, they believe that their time and effort will result in a desired extrinsic or intrinsic reward. For educators, autonomy and efficacy go hand in hand. Teachers are most effective when they have autonomy (decision-making power and the professional responsibilities that come with that power) and efficacy (the belief that their time and effort will generate their desired reward). The effort and self-determination of teachers contributes to their own sense of autonomy and to their students’ success. Teacher autonomy is not something that can be developed overnight, especially in communities where there has been tight control on curriculum, instruction, or teacher style. Schools or districts looking to increase teacher autonomy may want to make an investment in professional development for teacher leaders. Starting small and then building with a team is a great entry point to increasing autonomy for some, and creating a sustainable process for others to develop more autonomy. It is important to remember that teacher autonomy does not mean everyone does anything they want at any time, but rather that teachers are able to exercise professional freedoms for instructional and curricular choices focused on the responsibility of meeting students’ needs. This process can be developed and replicated. Schools interested in developing teacher autonomy can first focus on Department or Content area or grade level teams and develop a structure for meeting together, facilitation, and shared research. As teachers learn more about their field, they are better equipped to make decisions grounded in research. Instructional autonomy leads to the creation of a dynamic learning space, an increased growth mindset and a mindset towards social justice.

Learning environment

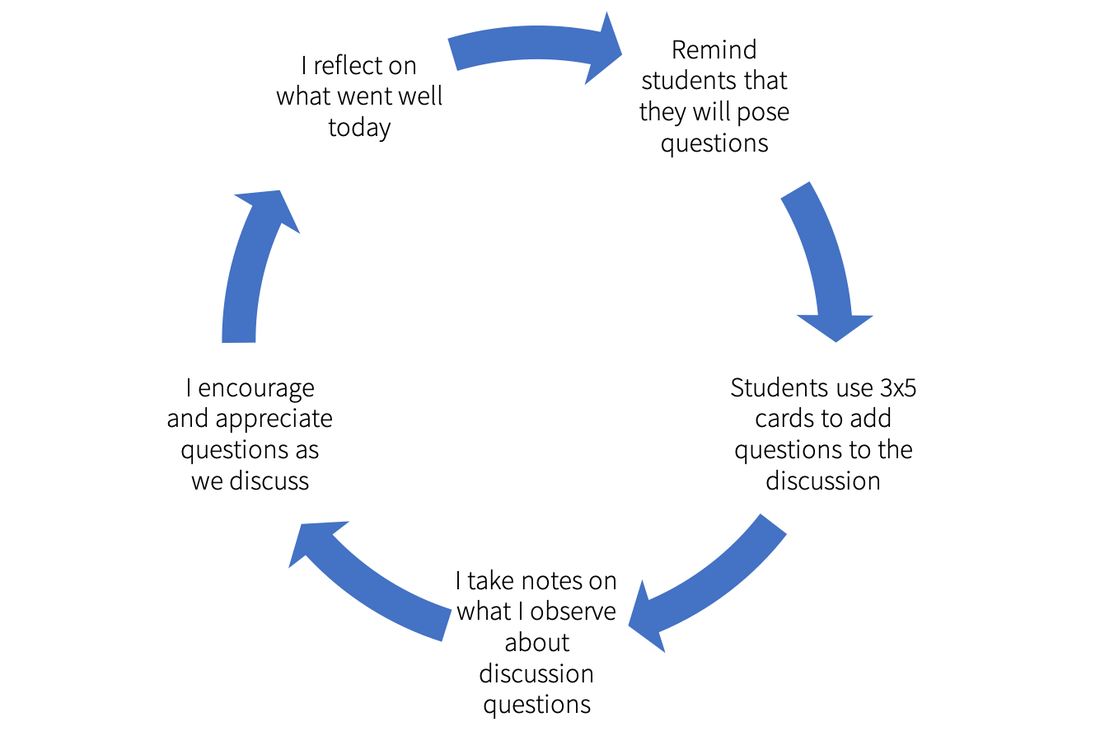

If we think of the word environment, as in habitat or place, the learning environment becomes the space where learning takes place. Curating a positive learning environment requires educators to consider how students learn best, under what conditions their learning can be maximized, and what disrupts the learning environment. Once these questions are answered, educators must use their available resources to design the physical or virtual space to create that environment. It’s important for teachers to think critically about creating a space for each student that provides access to resources, manipulatives, and intellectually stimulating tasks. This is commonplace in most elementary school classrooms which utilize their classroom spaces for strategic academic interactions — like the reading rug, the classroom library, and the conferencing table for students to work with their teachers individually or in small groups. All teachers create and cultivate learning spaces in how they interact with their students, how they utilize the space they have, and how they invent ways for students to interact with texts together. Rituals and routines play an important role in creating a learning environment that increases student literacy engagement. With a specific eye towards supporting English Language Learners, we can think beyond the physical resources found within a classroom space and focus on having a mindful routine, creating dynamic personal relationships between stakeholders, and developing instructional materials that are culturally and cognitively responsive to students. Additionally, when surrounded by physical texts and images of texts in the classroom spaces, students are more likely to engage in reading on their own. Implementing discussion is an integral part of the reading and writing process. When students discuss what they’ve read with their peers, it enhances their understanding, and their interest in the text. When students spend time and effort in retelling what they’ve read, creating a response to their reading, or synthesizing the text in new ways, their energy and effort has a direct correlation to their engagement in the reading itself. School and district leaders can support teachers to think deeply about their learning environment by being explicit about the resources available to teachers, as well as clarifying a theory of action that articulates how students learn best and translating that theory into an action plan for the learning environment. Beginning with the theory of action, schools that take the time to develop a shared understanding and a shared approach to learning also reap the benefits of a faculty and staff who are aligned in their mindset and approach and as a result create culture and environment quickly. After articulating the theory of action, schools need to develop an implementation plan, and an accountability plan. How will they see their values come alive in the daily interactions across the school? How will they hold teachers and other school staff members accountable to their ability to translate vision into action? Resources may vary, but the constant in any educational setting are teachers and students, together.

Relationship building

Relationships support building bridges between challenging content and critical skills. The relationship provides an avenue for teachers and students to bridge differences and bond through shared experiences. These bonds become a highway for academic support and interventions. Teachers with a high level of professional freedom typically have the confidence and the creativity to create a positive and engaging learning environment, which will in turn create personal and social spaces for students to find themselves as readers. Those personal and social spaces are nurtured through student-to-student and student-to-teacher relationships. Sharing reading ideas is especially motivating for students. Whether there are formal or informal conversations, teachers and students who read and discuss shared texts create shared experiences and shared memories. These experiences create strong bonds between teachers and students and inform their identities as readers and writers. When teachers and school leaders want to increase engagement through relationship building, focusing on social-emotional learning can be a great entry point. Creating spaces for students and teachers to identify their feelings within a given assignment can avoid misunderstandings that develop hurt feelings and divide teachers and students, impacting culture negatively. For decades, teachers have found that stories are ways to connect students to themselves, to each other, and to their larger community. Reading and writing are both connected to an audience which makes the act of either an experience in connection. Supporting students academically must include supporting students relationally. When students are able to connect with themselves and their classmates; when they connect with their teachers and count them as caring adults in their lives, they have essential support to then connect with texts that will become the driving force of their learning. The real and deep need for strong relationships is a key component to student engagement in reading and writing.

Download the white paper: Centering Students for Literacy Engagement: Voice, Choice & Identity, A Review of Literature for Behind the Book, conducted by the Center for Professional Education of Teachers at Teachers College, Columbia University.

About Behind the Book

Behind the Book was founded with an instinctive sense that getting kids excited about reading could have a significant impact on their academic (and nonacademic) careers, encouraging depth and freedom of thought, a hunger for knowledge and an understanding and appreciation for worlds beyond the one they know. In the years since Behind the Book began scheduling author visits, programming has expanded and evolved to include art projects, field trips, dramatic activities, the publication of student anthologies and more. About the Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) Sponsored by Teachers College, Columbia University, internationally renowned research university, CPET is a non-profit organization that is committed to making excellent and equitable education accessible worldwide. CPET unites theory and practice to promote transformational change. We design innovative projects, cultivate sustainable partnerships, and conduct research through direct and online services to youth and educators. Grounded in adult learning theories, our six core principles structure our customized approach and expand the capacities of educators around the world.

A look at high-leverage areas for student engagement in reading and writing.

Excerpted from Centering Students for Literacy Engagement: Voice, Choice & Identity, A Review of Literature for Behind the Book, conducted by the Center for Professional Education of Teachers at Teachers College, Columbia University.

When it comes to compliance vs. engagement, we can generally agree that compliance is about conforming, yielding, adhering to cultural norms, and cooperating or obeying. Compliance is focused on a mindset of teachers (or adults) having power over students, rather than empowering them. Whether we’ve recognized it or not, many schools are dominated by compliance-oriented structures which often mimic the behaviors of engagement. When schools structure how students enter, exit, move throughout the building, where they sit, how they sit, when they can go to the bathroom or eat food, the learning environment is dominated by a power-over culture which has an impact on authentic student engagement.

Engagement, on the other hand, is more difficult to define. Research on engagement and theories of engagement date back over 50 years and come primarily from perspectives in the fields of psychology and sociology. Each field has contributed theoretical frameworks designed to articulate what engagement is, how it works, how engagement breaks down, and how to generate it. We may understand the theories behind engagement, but can we articulate what engagement looks like for students in school, with respect to literacy through reading and writing specifically? A focus on literacy engagement is critical because without a personal and intrinsic motivation to read or write, school becomes a space that stifles student growth and prioritizes compliance over engagement. When students can develop a personal, authentic engagement in reading (taking in information and ideas) and writing (expressing information and ideas), students can develop sustainably positive experiences in school that develop their self-efficacy and self-confidence.

Essential factors in engagement

In a research review on literacy engagement, produced by The Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) in collaboration with Behind the Book, we analyzed previously published reviews of literature and research studies on literacy engagement. Throughout the literature, student voice, agency, and confidence emerged as essential factors that lead to increased literacy engagement over time. While many attributes contributed to increasing student voice, choice, and agency, six high leverage areas surfaced: student voice, student agency, student confidence, teacher autonomy, learning environment, and relationship-building. Refer to our companion article: Centering Students for Literacy Engagement: Teacher as Interdependent Curator & Bridge-Builder to read more about teacher autonomy, learning environment, and relationship building.

How do you incorporate these in your practice? What support might you need to deepen your understanding and implementation of these attributes?

Student voice

Student voice can be cultivated through classroom culture, through reading, and through writing. Classroom culture accumulates the small, large, formal, and informal ways that students interact with one another and their teachers. Here, when their voice is either heard or silenced, it has an impact on how the student engages in classroom activities and tasks. Educators find ways to elicit student voice intentionally by creating windows and mirrors. Windows are opportunities for students to see themselves in the literature they’re reading. When teachers design prompts that help students make connections, find commonalities, or empathize with characters or situations they’re reading, they create a metaphorical window for students to see how they connect with a text. Alternatively, teachers can also prompt students with entry points to reading and writing that act as mirrors for students to see their thoughts and feelings emerge on the page as they write or draw. Mirrors reflect our identity, and mirroring tasks and texts give students an opportunity to see themselves as valid, legitimate, and important enough to write about. Through publication projects, drawing, drama, and the wide variety of activities teachers can plan, centering student voice is a key factor in reading and writing engagement. For example, when educators place students in the driver’s seat of the drafting, revising, editing, and publishing process, student publication projects support students to both find their voices and to broadcast them. Teachers can invite all student voices by creating classroom spaces with a mix of culturally responsive teaching characteristics such as communicating high expectations for all students, expressing positive perspectives on parents and families, practicing student-centered instruction, and reshaping curriculum to meet all student learning needs. What makes some students more readily able to access and raise their voices is influenced by how the teacher designs a classroom space where students feel free to use their voices.

Student agency

Cultivating in-school literacy experiences that highlight student voice, agency, and influence is in sharp contrast to the drill and kill test prep approach that many teachers feel is necessary to get students to pass the test at the end of the school year. But this is precisely where students need to have their identity, voice, and influence emphasized. Student engagement increases when educators deliberately create a culture that does the following: expects students will give feedback to their teachers about their experiences in class; expects students will share what they want to learn; and expects students will share how they want to learn. The student engagement from this culture occurs when teachers respond to those suggestions by making visible changes to instruction. Specific practices include students performing their writing, conducting research with adult allies, and having forums where student voices, ideas, and lived experiences are prioritized. Authentic or real-world reading and writing tasks increase student engagement. When the audience for writing widens to include people in addition to one teacher, such as letter writing to local politicians, posting poems on classroom walls and stories in school hallways or publishing a class book in which each student authors a piece and reads it aloud during a celebration and book signing ceremony, students experience an increased sense of agency and engagement in the writing process. Student authors connect their writing to a larger purpose, and writing for an authentic audience allows students to gain skills and perspectives that will serve them beyond the classroom. Dynamic and long-lasting engagement comes from the combination of student agency (how do students use their voice to influence their education?), community (how do the people surrounding students influence their perception of school?), and the organizing structures of school (how does student voice influence the structure and organization of the school?). When students choose for themselves, they exercise their own agency, which can increase the strength they feel when attempting to express and act upon their own goals and values.

Student confidence

Confidence is often seen as something that someone either has, or doesn’t have, as if the belief in oneself was a static perception that was either present or not present at birth. However, we know from Carol Dwek’s work on the Growth Mindset that our intelligence and our sense of self evolve over time, and that our self-perception is never at a fixed point. Respected and caring adults in students’ lives have the amazing power to influence students’ perceptions of themselves and others. There are varied ways to build student confidence, including consistent use of authentic writing tasks, reading choice, and repeated reading practices. Increasing student confidence is complex, requiring innovation and persistence from students as they move toward their educational goals, as well as from teachers on behalf of their students. Educators can make choices to provide an array of differentiated reading and writing tasks, integrating student voice and choice into the mix and building their confidence with each new learning opportunity. Required readings, assignments, and projects can be shared at the start of a school year, semester, or unit and teachers can then support students in finding their unique and desired ways to process and express their connections to the reading and writing Valuing a student’s home language and utilizing it as a linguistic tool to problem solve, communicate, and access materials develop students’ literacy skills and self‐confidence. Even in situations where younger students are learning English as a Dual Language, their ability to negotiate the language will have a major impact on their motivation to read and write, or to not read and write. The same can apply to older students who are learning English as a New Language. Whatever the age or nuanced way of referring to learning a new language, when language creates a barrier to entry, students are more likely to give up than they are to keep trying. When students new to learning English can talk with their classmates in their home language, think through complex ideas in their home language, write out their notes in their home language — they’ll have increased confidence in their understanding of the concepts and can, as a separate task, get to work on translating their ideas into English. Success cycles are built when educators better understand how to design their instructional tasks to incorporate opportunities for student voice, agency and confidence.

Download the white paper: Centering Students for Literacy Engagement: Voice, Choice & Identity, A Review of Literature for Behind the Book, conducted by the Center for Professional Education of Teachers at Teachers College, Columbia University.

About Behind the Book

Behind the Book was founded with an instinctive sense that getting kids excited about reading could have a significant impact on their academic (and nonacademic) careers, encouraging depth and freedom of thought, a hunger for knowledge and an understanding and appreciation for worlds beyond the one they know. In the years since Behind the Book began scheduling author visits, programming has expanded and evolved to include art projects, field trips, dramatic activities, the publication of student anthologies and more. About the Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) Sponsored by Teachers College, Columbia University, internationally renowned research university, CPET is a non-profit organization that is committed to making excellent and equitable education accessible worldwide. CPET unites theory and practice to promote transformational change. We design innovative projects, cultivate sustainable partnerships, and conduct research through direct and online services to youth and educators. Grounded in adult learning theories, our six core principles structure our customized approach and expand the capacities of educators around the world.

Make sense of your thinking as you articulate the what, why, and how of your lessons.

My most common resistance and response, when prompted by our director to articulate my next workshop plan in one of our templates is, “We don’t have time for that. I need to get in there and get the work done. I don't have time to also articulate what the work is going to be.” After I express my frustration with a lack of time, I take a breath and sit down with my thoughts, our goals, and the template.

Thankfully, the template has been through our usual practice of draft, revision, practice, and more revision, so that I’m working with a helpful, useful, and practical tool. As I move through prompts like driving questions, objectives, skills, activity, assessment, and resources, I see what’s in my head come together on the screen. By the time I’m done, I’ve experienced the magic of a pre-planning template. I’ve actually done all the work of thinking through what I’m doing, why I’m doing it, what skills I need to teach, and how I will confirm what students know and can do throughout the workshop. Not enough time to plan? I actually don’t have enough time NOT to plan! As it turns out, articulating my plan supports me in grounding the lesson in its larger context and provides a way to make my thinking visible to my students, my colleagues, and my supervisor. Bonus: I won’t need to reinvent an agenda the next time this workshop rolls around. I have a lesson plan I can reuse and customize going forward.

Our lesson planning resource supports teachers like you in experiencing this same process — moving your thinking from inside your head out into the world, and considering all of the pieces of a lesson, because the template reminds you with supportive prompts. You can leave yourself room to think more deeply about teaching and learning by relying on our preset categories to pull you through your planning time.

It’s important to be confident and clear about your plans, and articulating your thinking is an excellent way to get there. This is what will allow you to be more flexible, because you’ve got a plan from which to work. You know what’s essential and what might be able to shift when unexpected changes occur in your classroom, as they so often do! You can use this resource as a tool for yourself as we teach, your students as they engage in the work, and your colleagues as you offer each other formal or informal coaching in this challenging and rewarding world of teaching.

Understanding the connection between what is taught and what is learned is a vital part of your classroom practice.

One effective tool we use when delving into new content is the resource It says...I say...So... With this tool as our guide, we can explore Danielson’s Framework for Teaching, 3d Using Assessment in Instruction.

Danielson 3d says...

“Assessment of student learning plays an important new role in teaching: no longer signaling the end of instruction, it is now recognized to be an integral part of instruction. While assessment of learning has always been and will continue to be an important aspect of teaching (it’s important for teachers to know whether students have learned what teachers intend), assessment for learning has increasingly come to play an important role in classroom practice. And in order to assess student learning for the purposes of instruction, teachers must have a “finger on the pulse” of a lesson, monitoring student understanding and, where feedback is appropriate, offering it to students.”

This means...

This looks like...

This is challenging, because...

So...

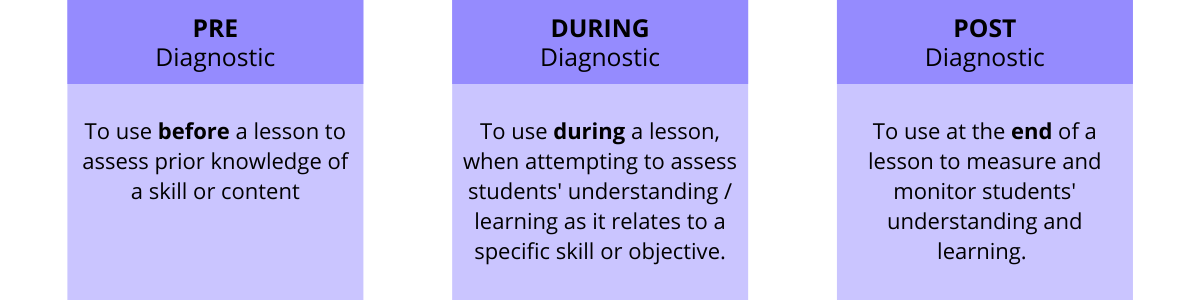

Let’s consider formative assessments. They are most helpful to us when making instructional decisions. They are used to monitor student learning and inform feedback. They help give us an overall picture of a child’s achievement. Formative assessments are used throughout the lesson.

You can try...

Below are a few examples of practical pre-instruction assessments you can try in your classroom.

What are you trying in your classroom? What do you want to integrate into your practice? Tell us more in the comments! Learn more about opportunities to Design Coherent Instruction for your students.

Happy teachers tend to be wonderful teachers.

Did you ever get one of those letters? Those notes written in crayon or #2 pencil? Those sweet messages with a picture drawn at the bottom? Some of us remember those. We may have them tucked in drawers or taped in journals. Some of us remember emails or texts, sometimes years after our students graduate. They might have shared a memory or thanked us for a positive moment that stuck with them.

Those messages can help us float above the floor for a few minutes or keep us grounded for the day. What an encouragement! Here we are, in our next normal — whatever that looks like after whatever we’ve gone through. It seems like a good time for a letter from some of your colleagues with practical encouragement that builds our practice of supporting ourselves and each other.

Dear Teacher,

Happy teachers tend to be wonderful teachers. To be happy you have to figure out how to take care of yourself. It's not selfish. The trick is to figure out how best to take care of yourself, and then be deliberate about doing it. Nobody can do this but you! (I learned this a few years ago — I was late to the party)! I think it's important to make time for yourself, otherwise you'll burn out. Even on my busiest weeks, I value taking a little bit of time to be human. That might look different for everyone, so find a practice that centers you — whether that's working out or gardening or just reading mindless BuzzFeed articles. Making time for yourself is essential; not optional. Whatever you do, MAKE the time — otherwise you will burn out and be of no use to anyone.

With five minutes, you can:

With 30 minutes, you can:

With an hour, you can:

Thanks for being a teacher! Take this letter and tuck it away or tack it up somewhere to remind yourself to care for yourself first.

With love from your CPET colleagues, Ashlynn, Faith, Laura, Marcelle, Sean, and Sherrish

Recognize the motivations behind behaviors that block success and explore how to respond appropriately.

A social media post ignites a tiny fire, and the fire blazes as people pour fuel in the form of dislikes and comments accusing one another of being wholly disrespectful to a person, people group, larger community, or an entire country. From social media to the dinner table to the holiday family gathering, we hear words and actions that offend us, and we attribute disrespect or out and out defiance to the person across the table. So much disagreement, so many approaches.

The same goes for our classrooms, right? We’re teaching and a student rolls their eyes or puts their head down – but wait, before we even got to this teaching moment, we spent hours in backwards planning for our unit and prepared an essential lesson to our topic — and now, we’re getting disrespect in return? It’s easy to give up, but what if we approached what we’re seeing in a different way? What if we get curious about what it is we’re noticing in student behavior?

Responding vs. reacting

Our resource for tackling off-task behaviors — Behaviors that Block Success — helps us respond rather than react. We consider that there are four types of behavior that have a negative impact on the classroom environment, and it’s important to be able to recognize what each behavior type looks like, as well as the motivations behind it. This is what will allow us to act responsively.

We can use this resource as a tool to interpret student behavior in a constructive way, cultivating curiosity in ourselves. In order to interpret behavior, we must challenge ourselves to see beneath the surface and identify why the behavior is happening. When encountering inappropriate student behavior, our goal is to respectfully communicate the expectations, de-escalate the conflict, and maintain teacher authority. We can review the behaviors, make connections between what we are seeing and what we already know about our student as a whole person, and ask the student what they’re experiencing as well. This will open up communication by demonstrating respect for the student and asking questions instead of jumping to conclusions.

Imagine having this resource out on your desk during class, picking it up when you’re struggling with what you think might be defiant behavior and considering all the possibilities. Put it up as a poster, and share with your students that you’re trying something new or adding to your toolbox.

You’re all learning together, and no one is on the “other side” of anything in the classroom, so why not make it clear to both yourself and your students?

Breathe new life into book clubs and place students at the center of their reading experience.

Time moves forward, as it always does. We can take this time to reflect on lessons learned when we unexpectedly and quickly shifted from teaching in the classroom, to teaching remotely, and then into a next normal of blended in-person and virtual learning spaces. One big takeaway from this time of critical reflection is that we aren’t starting with a blank page. Whatever the season, we can adapt tools we already have to meet the challenges we’re facing.

Breathing new life into book clubs

New tools can breathe new life into our planning and our teaching, and creating a new tool doesn’t need to be done from scratch. By connecting Ten Tips for Successful Book Clubs with our Global Mindset Framework, we can quickly create a new resource that integrates teaching 21st century skills into each reading opportunity we plan for our students. Book clubs offer many benefits to student readers, including:

A successful book club for your students will:

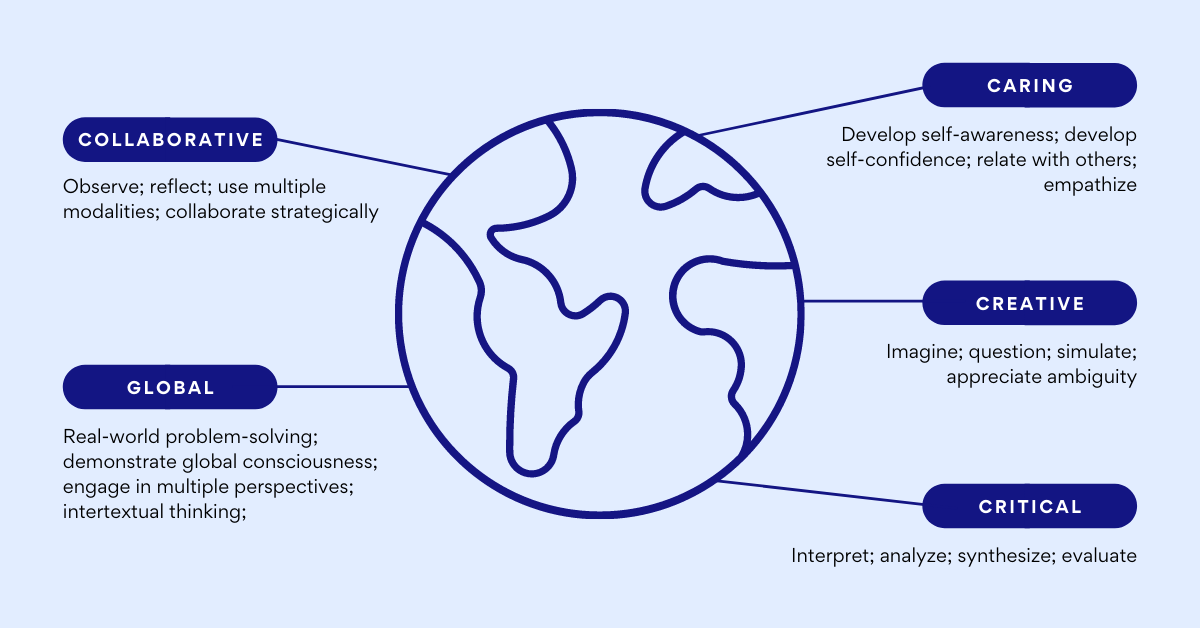

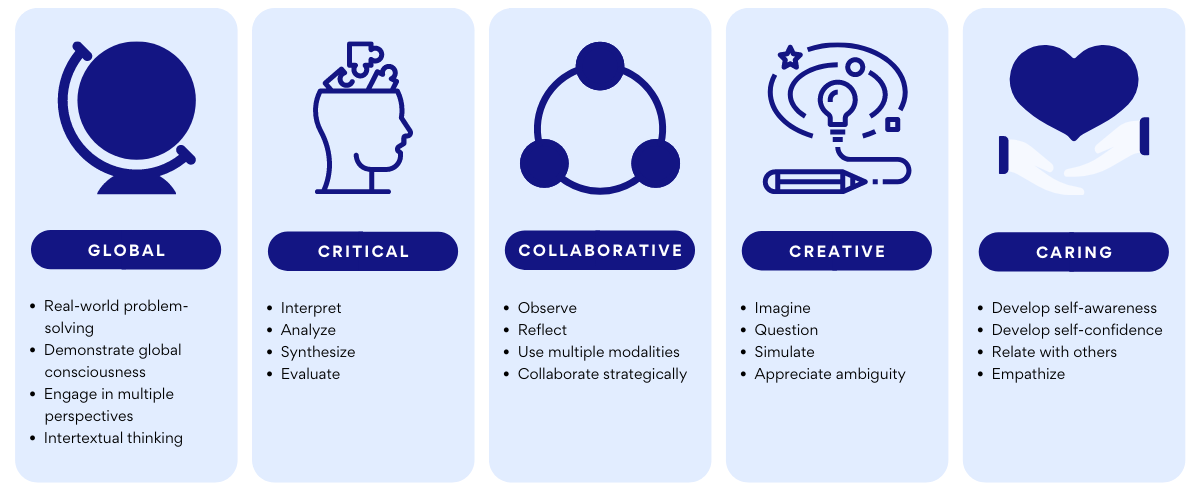

Understanding the Global Mindset Framework

Now that we’ve framed some of the characteristics of book clubs, we can connect each facet to our Global Mindset Framework. This will help us streamline our work when planning for our next book club iteration, or beginning a book club community with our students.

The Global Mindset Framework is the articulation of 21st century skills students need to navigate their present and their future, sorted into five categories of capacities: caring, collaborative, creative, critical, and global. The framework addresses key questions that teachers and school leaders struggle with as they attempt to make key concepts relevant to children in a changing world. To understand the Global Mindset Framework, we can look to the Global Learning Alliance (GLA). The GLA is the outgrowth of our groundbreaking research on the features and practices surrounding 21st century teaching and learning. It has evolved from the seeds of a research project and is now a consortium of schools and universities around the world dedicated to understanding, defining, applying, and sharing the principles and practices of a world-class education within a wide range of educational contexts.

21st century capacities

Global capacity: The capacity for students to step outside the confines of their own familiar social world to understand distant realities in order to engage productively with the world. Critical capacity: The capacity for students to develop their full critical cognitive capacities in order to be discerning and informed citizens of the world. Collaborative capacity: The capacity for students to develop habits of observation, reflection, and collaboration, and to be able to communicate in multiple modalities such as through images, words, sounds, gestures, or an integration of these modes in order to actively contribute to various discourses in the world. Creative capacity: The capacity for students to follow their curiosity by questioning or imagining in order to contribute positive improvements or inventions to their world. Caring capacity: The capacity for students to explore compassion, empathy, and self-awareness in order to develop caring partnerships with themselves, their communities, countries, and world.

Activating 21st century skills

Using the template below, we can imagine how we might combine various capacities from the Global Mindset Framework with our tips for success to generate a profile of a book club that integrates 21st century skills into student learning. We want to keep moving our teaching forward to meet the needs of today’s students, but we don’t often feel we have the time we need to recreate our plans. By layering the Global Mindset Framework over our book club planning, we can revise what we’ve already got going for us instead of starting from a blank page.

Connecting skills to next steps

Using the template above, we can customize our profile to fit a specific book — in this case, we'll use Malala Yousafzai's I Am Malala: How One Girl Stood Up for Education and Changed the World. In this model, we start with our to-do list; we imagine some of our options, and what we need to collect to complete our plan.

The task before us all is to educate students today for the world they’re poised to lead tomorrow, and as we recognize that we can no longer sustain a 20th century in a 21st century world, we must remain flexible in order to meet the dynamic needs of our students. As we look for ways to build upon the expertise and techniques already alive in our classrooms, we can easily create opportunities for students to build 21st century skills, shifting from teacher-centered instruction to an environment that puts students at the center of their reading and writing experiences.

Engage in reflection, gain self-awareness, and pinpoint an area you want to develop further.

Perhaps you, like me, have searched for ways to create more space, and you’ve added a new practice or two to your routine, like taking scheduled walks, meditating before class, keeping a journal, or adding breathwork before dinner. Maybe the ideas you’ve uncovered don’t seem to integrate into your professional life. Sure, they’re great if you have all the time and space to engage in them, but let’s be honest — there seems to be even less time for that elusive self-care now that work days stretch from dawn until well past dark. Reading article after article on how to manage stress may have resulted in a lot of ideas, but little implementation. That’s normal. We all need support to take our next steps, and starting with the smallest thing could make the biggest difference.

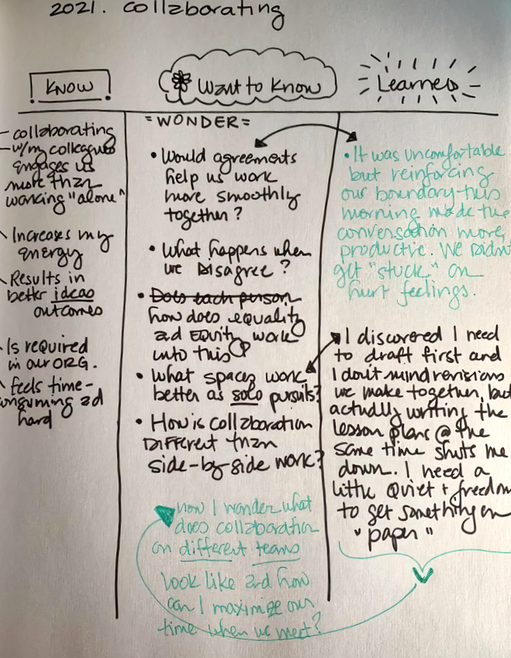

K-W-L

As we move deeper into the year, we might look to practices that feel more authentic to our teaching selves. Using a familiar tool can provide a valuable structure, bridging the best of our personal pursuits with our professional realities. We may be familiar with K-W-L (Know - Want to Know - Learned), a reading strategy which serves as a self-propelling guide for students as they read through a text. Students begin by charting everything they know about a topic in the K column. They move on to generating questions about what they want to know about the topic. During and after reading, students document what they have learned.

We can chart what we know, want to know, and have learned about anything at all, including our own professional development and the self-care habits we need to keep going strong. This process draws on our own prior knowledge, sets a purpose for our routines, reveals obstacles, and documents our progress, giving us the opportunity to both plan for our success and to celebrate steps we take along the way. Below is my K-W-L example, which is focused on collaboration, because that is an area I want to develop in my professional life. My “texts” are a combination of reading and action. In one case, I was having trouble maintaining my boundaries with colleagues. I read an article that felt more personal in nature than professional, but when I took action to make self-care a priority, (#7 in the article) I found myself carrying over some practices into my professional life. I began to honor my own feelings instead of pushing them aside in deference to others. My feelings were signaling when my boundaries were crossed, and I could then address that within myself and with my colleagues. Identifying your how

What it seems we have more than enough of is access to ideas on what to do, like this idea about using a K-W-L in a new way, but we’re short on the how.

My how emerged out of my needs and came out in three steps:

Simple supports

Even when we know the how, we also need support. Support can come in many different forms. Consider a few of the following simple ways to create support for yourself:

Using a K-W-L structure is one way to engage in reflection, gain self-awareness, and pinpoint an area you want to develop further. Returning to the "L" column can help you feel a sense of accomplishment, or at least identify a new place to begin work. Whether you want to chart about any of the hundreds of self-care options out there or you want to chart your progress toward specific teaching goals, by using K-W-L as a way to drive inquiry, we can uncover some answers, more questions, and plenty of celebration on the small and large steps we are taking as we continue evolving.

Offer your students an opportunity to authentically engage with content, even when learning remotely.

Over the past year, school has been a rollercoaster event filled with openings, closings, virtual connections, and dramatic shifts in teaching and learning techniques and experiences. No matter the grade level or subject area, our learning spaces have been completely redefined. And it isn’t just due to in-person or online learning schedules — many teachers are finding that what worked in person may not be working as well online or in other virtual settings. Additionally, changes to state tests and other accountability measures have created opportunities for teachers to redesign their teaching methods and learning outcomes to authentically engage students in the core elements of their content areas.

Finding ways to engage students in content can be difficult, particularly when so much teaching and learning is happening remotely. We understand this challenge. Our Literacy Unbound team faced the same concerns about how to engage teachers and students in our 2020 Summer Institute — traditionally a 2-week, in-person immersive learning experience. Rooted in the belief that students learn best through authentic inquiry, curiosity, and through the multimodal embodiment of a text, Literacy Unbound brings teachers and students together with teaching artists to explore the in-depth themes of a shared text, independently. In a typical summer, we would develop a series of Invitations to Create as a way to invite and entice students into the world of the text. These invitations might prompt readers to journal, draw, collage, create a playlist, or explore some other form of expression related to a key quote or “hotspot” in the text. As readers collect their responses, they traditionally come together for a dynamic experience in which they construct an original performance based on their responses to the invitations. While much of the in-person institute needed a complete redesign to fit a virtual institute, the structure of Invitations to Create did not. Invitations provide the perfect setup for virtual reading, writing, and collaboration. And they come with plenty of choice, freedom, and personal exploration, which means that participants can be authentically engaged from the very beginning.

Creating your invitation

Even though Invitations to Create begin as prompts to pieces of literature, they’re extremely flexible and are a promising practice for all content areas and grade levels during remote and/or blended learning experiences. How can we begin to incorporate invitations into curriculum for math, science, and social studies, and beyond? To get a sneak peek of the process, we’ve developed the sample below to experiment with Invitations in Mathematics, adapted from A Guide to Crafting Invitations to Create by Dr. Nathan Allan Blom. Note: As you read, look for the examples in blue of building an invitation for A Mathematician’s Lament.

Step 1: Jot

Whatever the content, there are literacy expectations in your field. What are the reading and writing requirements in your field? In your course(s)? In the exam? Jot down some of your thinking as a warm-up. Step 2: Identify What is a text you go back to over and over again that you want to introduce to your students — or -- what is a text you already plan to use in a future lesson? Have the text handy.

A Mathematician’s Lament by Paul Lockhart

Step 3: Choose Choose a “hotspot” within the text. This is a passage of the text that captures your attention. Typically, it’s helpful if a hotspot contains:

Explain in a few words the context of the hotspot within the larger text.

In the first chapter, the author shares about a nightmare an artist has about how art is taught so that children don’t hold a paintbrush until they are young adults. Instead, they learn about art for years before they experience it for themselves. He says that life is very much like that in the real world of mathematics:

“Everyone knows that something is wrong. The politicians say, “We need higher standards.” The schools say, “We need more money and equipment.” Educators say one thing, and teachers say another. They are all wrong. The only people who understand what is going on are the ones most often blamed and least often heard: the students. They say, 'Math class is stupid and boring,' and they are right.” Step 4: Offer Offer an idea you had or a connection you made during your reading. Share with the voice of a fellow student, rather than an authority on the subject.

This makes me wonder how much more often math is seen as boring instead of beautiful.

Step 5: Connect Connect the hotspot to a piece of media to illustrate and/or extend your connections, questions, or ideas. Explore media to find something that connects and inspires you, like:

Video: The Beauty of Mathematics

Step 6: Prompt Create your prompt, using this structure: In whatever way seems best to you (equation, movement, experiment, poetry, prose, music, art, video, etc.), explore ______. Let's look at our invitation for A Mathematician’s Lament created from steps 1 - 6:

A Mathematician’s Lament by Paul Lockhart

In the first chapter, the author shares about a nightmare an artist has about how art is taught so that children don’t hold a paintbrush until they are young adults. Instead, they learn about art for years before they experience it for themselves. He says that life is very much like that in the real world of mathematics: “Everyone knows that something is wrong. The politicians say, “We need higher standards.” The schools say, “We need more money and equipment.” Educators say one thing, and teachers say another. They are all wrong. The only people who understand what is going on are the ones most often blamed and least often heard: the students. They say, 'Math class is stupid and boring,' and they are right.” This makes me wonder how much more often math is seen as boring instead of beautiful. Listen and watch this: The Beauty of Mathematics In whatever way seems best to you (equation, collage, drawing, music, etc.), explore the idea that, in the real world, math is beautiful. Include directions about how students will share their creation with you and each other. This process supports students to make their own meaning of the text, and is also a way for you and your students to experience an invitation together, whether you’re in the same concrete or virtual space. If possible, create your own response to the invitation and share it at the same time your students share theirs.

Each invitation offers an opportunity to reflect, analyze, and synthesize the text at hand. Once the invitations have been developed, students are invested in their interpretations and eager to share their ideas. This sharing is a powerful tool, inspiring motivation and encouragement across the community.

What can you invite students to create using this simple and effective structure?

We must face the realities of our current teaching and learning situation — and then find ways to adapt.

The sunlight is still Summer while the breeze feels like Fall. Teachers stream in, eager to find their names at check-in and chat with colleagues on their way to hear the keynote speaker frame the day, “It’s not that differentiation is part of the work. Differentiation is the work itself. We all can make progress and we can all grow. Each student deserves a goal that they can work hard to achieve!"

This excerpt from a previous post about bringing a series of in-person professional development workshops to life evoked memories that seemed to stand in stark contrast against our current teaching and learning situation.

Adapting our plans

We began our Spring 2020 workshops series on a cold day in February. At the end of the day-long sessions, facilitators reviewed feedback from participants, noted adjustments they would make to their plans, and tucked away sign-in sheets in folders, ready for their next session — a month away. A few weeks later we found ourselves siloed, setting up spaces at home where we could work, on screens, day and night. It felt as if we were living in a snow globe that someone picked up, shook, and set back down, leaving our environment sloshing around us, debris floating through the air, settling at our feet. We moved quickly, collaborating from our siloed spaces, pushing one another to reframe our thinking:

Through connection and communication, we were able to find ways to support teachers who were going through the same process themselves: expanding their classroom from inside the walls of a school building out in the city, across the state, and around the world. The phrase we're in this together became a mantra not only when it came to wearing masks, washing our hands, and social distancing, but also when it came to our own teaching and learning. Stay-at-home restrictions created an environment in which we needed to open our minds to as many options to meet as many students in need as possible. As teachers — from early childhood education to graduate school — revised and remodeled their plans, many began to ask, “Why didn’t I think of this before? I could have a distance learning component for each of my lessons.” At CPET, we realized that we could not only offer each of our workshops in an online space, but we could make all of our offerings available at no additional charge to our participants. The limitation of being in a specific session at a specific time was gone, and what was left was the opportunity for teachers to experience as many of the asynchronous offerings as they cared to.

Our Spring 2020 asynchronous offerings; view upcoming opportunities here

Utilizing practical strategies

Of course, after plans are adapted into a new space, the work again becomes customizing to our students. What do our first graders need to connect during distance learning? What about our sixth graders? Our seniors? As our snow globe settles and our vision clears, we see that trusted strategies are a foundation we can still hold on to. We can identify practical and adaptable tips we’ve used in the classroom and integrate them into our remote teaching and learning.

So, we end where we began: differentiation is not simply part of the work — it is the work.

Each student deserves the opportunity to grow, demonstrate progress, and work hard toward an achievable goal. Each teacher deserves the same.

Listen to children at every age. Meet them where they are, in the best way you know how. That will be more than enough for the moment we’re in.

In a recent letter to the community, CPET Director Roberta Kang shared her childhood memory of the Challenger Space Shuttle’s explosion, and her experience as a teacher in the classroom during 9/11. She wrote, “As educators, we are not unfamiliar with working through a crisis. We know that some crises are visible, and some are invisible. We know that some are explosive, while others are slow burns that dismantle a sense of safety bit by bit. We know that some have villains attached, and others are just, well, science.”

Our children will have strong memories of this time. They will recall what it was like when their school closed, when they had to wear masks, stand far away from people, or when open air parks were locked to visitors. Already, children are telling stories about when they went to school, “before the virus came” and what they want to bring to school, “after the virus is over.” Having conversations with children about what is happening around them and within them will support their growth and learning during this challenging time. Although COVID-19 is a new type of coronavirus, talking with children about scary situations is not new. To support our conversations, we can lean on reliable resources and use age-appropriate methods. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) connects their general principles for talking to children to the National Association for School Psychologists guidelines:

There are many resources online to support our conversations, and it can be overwhelming to sift through for “the perfect one.” During this time of emotional, mental, and physical overload, it’s important to remember there is no such thing as perfect. Using a reliable, science-based option will give you a starting place for you and your kids to generate questions and keep the conversation open.

Pre-K — Elementary

Support your younger students with ready-made resources from PBS. Sesame Street’s Caring for Each Other page has informative, age-appropriate videos and free e-books to support your conversation about what COVID-19 is and what we can do about it. Use their infographic to prepare for your conversation if you are feeling concerned about what to say. Older elementary students can learn more about germs and build their vocabulary by reading an article together, like What are Germs? — available in English and Spanish, with an option to listen to the article while you read.

Middle school

Middle school students are moving into a space where they question the answers they are given. Use this natural developmental stage to engage kids with inquiry cycles. Consider not only a focus on COVID-19, but a student exploration into a simple history of viruses. Whether you adapt lessons from online sources, like three lesson plans for science, math and media literacy focused on COVID-19, or you set students on a path to conduct their own research, trying out an inquiry cycle can help students gather information and generate real questions that lead to deeper exploration. Don’t have a template of your own? Give ours a try — within this template, students can share their findings in discussion groups while you use the written information as formative assessments, make adjustments to lesson plans, and provide supplemental materials or advice for students as they explore. During this time of distance learning, we have the opportunity to see what happens when self-discovery and experimentation places learning in our students’ hands. As students get more autonomy, we get to see firsthand what teaching looks like when students are at the front of the class.

High school

Students at this age can do their own research on the topic starting with the CDC’s Coronavirus-19 page (available in at least five languages), which covers symptoms, how to protect yourself, slowing the spread, daily life, and coping and is updated regularly to include subjects like cloth face coverings. As new questions arise, students can create a simple art project, like an infographic. With them, you can research to find answers, add them to your infographic and draw, color, or paint for emphasis. If infographics aren't your thing, consider having kids create one of the following to illustrate their research:

Above all, listen to children at every age. Listen to their words. Listen to their behavior. Meet them where they are, in the best way you know how. That will be more than enough for the moment we’re in.

Approaching change as if you’re training for hurdles is a practical way to address and overcome any fears that may surface.

Fear of change is real and challenging.

Fear manifests itself in different ways for each of us, whether it means becoming defensive in the middle of a coaching conversation, avoiding a colleague you’re paired with, or becoming paralyzed at the prospect of dealing with conflict directly and openly. As Roberta Lenger Kang noted in Don't take it personally: de-escalating conflicts in the classroom, “The more fear we have, the more likely we are to become hyper-vigilant micro-managers in the classroom, which can sometimes magnify small issues and escalate conflicts…” Whether you’re affected by a change taking place or you’re implementing change that will affect others, treating the process as if you’re training for hurdles is a practical way to address and overcome fear of change in yourself and as you lead others. This training can be broken into three parts.

Before change: flexibility and preparation

Before enacting a change, stretch, practice, and count. Stretch: Whatever the change, find where you already have some flexibility and elongate it.

Practice: When preparing for a change, implement small steps on your way to the starting line or implementation date.

Count: When leading change, you know teachers will have some level of anxiety or fear of change. It’s normal.

During change: keep moving forward, but pace yourself

During a process of change, speed up toward the first hurdle, run steady through the middle, and finish strong. Speed up: After laying the foundation for the change ahead, consider taking the first hurdle of actual change with excitement, energy, and speed. With a little extra energy, you can leap through the discomfort and make it over the first goal.

Run steady: After the initial hurdle, move forward steadily, pacing yourself as you go. You’ve already entered into a new way of teaching, so keep the changes to a minimum.

Finish strong: As you round the corner toward a natural check-in point, gather some energy.

After change: celebrate and reflect

After implementing change, allow yourself time and space to reflect on your experience and celebrate your successes. Celebrate: Pick a finish line. The finish line may be obvious, like the end of a unit or the semester. It may be decided by administration based on an outside deadline. It could be ongoing, like making a change that lasts the entire school year and beyond. If that’s the case, choose a check-in as your finish line. When you get to the finish line, celebrate. You did it! You engaged in change. You may or may not feel like it went well, but that doesn’t affect the celebration. To celebrate, you simply share with yourself, and others if possible, that you made it to a finish line! Find a way to concretize the celebration, whether in writing, capturing your success using social media, or sending an email to people who care about you. If you’re leading change, consider making a well-deserved certificate for your teachers or students to commemorate their progress. Reflect: To make the most of your experience, find the time to reflect. Find ways to adjust your practice going forward, and ask more questions about what is possible. What went well? What would you like to see more of? What questions came up that you’d like to explore? Journal, use a template (create your own or download our What, So What, Now What tool), or make a list of what you want to talk about with your academic coach or colleagues. Hurdle after hurdle, make a habit of attempting your jumps. Whether you sail over them, tip them, or knock them over, you’ll give yourself the opportunity to learn from every leap and fall.

Strengthening your communication with students and families can seem daunting. How can you get started?

“The importance of good parent-teacher relationships has been well documented. Research has shown that parent involvement in education benefits not only the child but also the parents and teachers.”

We want our students, parents, and teachers to experience these benefits.

Challenges are easy to list, and we likely have a long list beyond these, but here are some of the big ones.

Start by planning

Strengthening your communication with students and families can start as simply as organizing your approach. Whether you’re approaching the beginning of the year, a new term, or are in the middle of a course, trying a new tool that can be customized to your unique communication style and your school’s expectations for family contact will support your work.

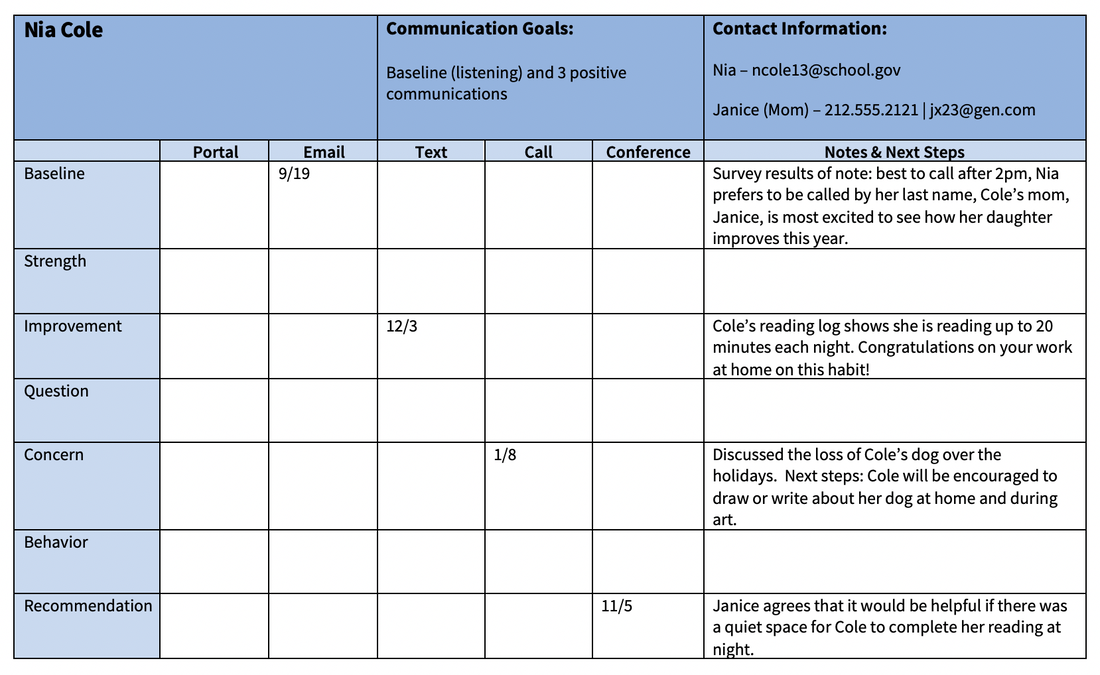

Communication goals

In the example below, our first goal was to start with listening, in this case using a baseline survey to the student’s parents that establishes a connection and supports us in understanding our student from the parent’s perspective. Our second goal was to have three positive contacts with the family, in addition to any contacts necessary to discuss issues that may arise in the classroom. From here, we would continue to add our notes and check in on communication that may be needed in order to meet our goals. This template can continue to be streamlined or expanded as practices change over time. While the content of parent/teacher conversations may not always be easy, simply getting started can give you confidence and increase the ways in which you can connect with families.

Ways to get clear feedback that can inform further instruction.

We check for understanding constantly, don’t we?

“Does that make sense?” "Know what I mean?” “Get it?” When it comes to our classrooms, we’re looking for more precise ways to check for understanding. Here are some simple ways and a few tools to use in your class as soon as tomorrow!

Thumbs up!

A simple and positive hand gesture can check to see who is hearing your instruction and who needs more support to move forward. You can use this:

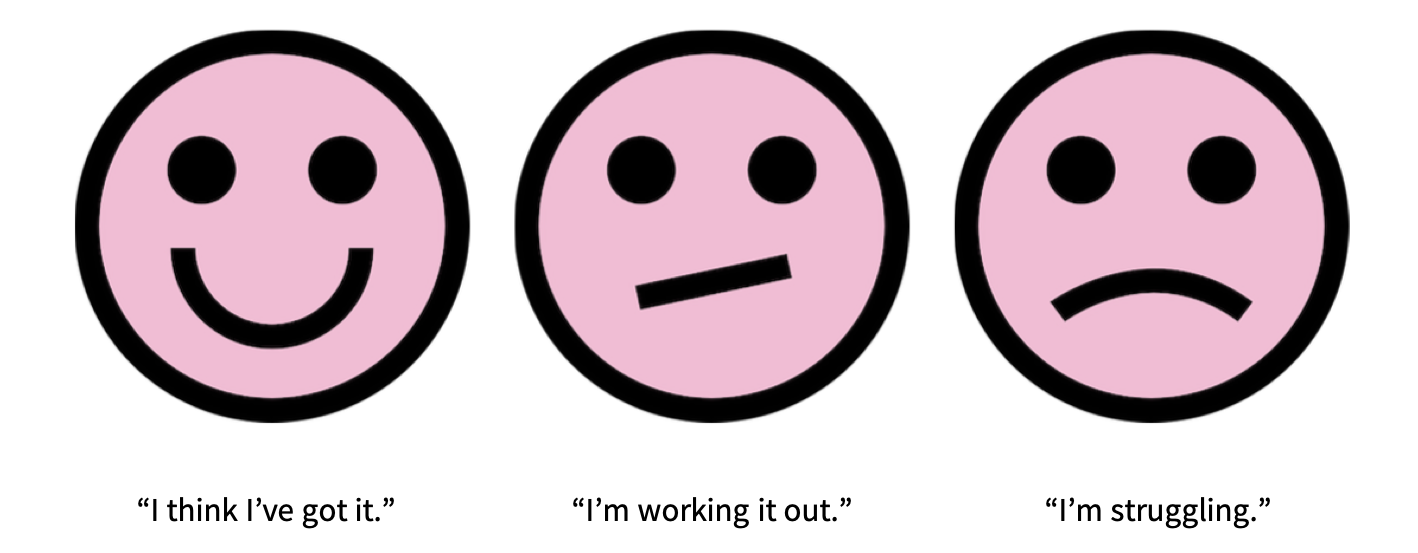

Choose your emoji

Expressions are a helpful way for students to share how they’re feeling or thinking about new or challenging content. It is especially useful for English Language Learners and Students with Disabilities. Using emojis (which can be individual cut outs or together on one piece of paper), ask students to choose the emoji that best represents their current experience. As you move around the room, you can customize your questions and support. Find out more about what the happy faces understand, what the thinking faces are working out, and what the sad faces need to make their struggle productive.

Entrance tickets

See how the homework informed thinking or where yesterday’s mini-lesson landed by collecting a little data at the beginning of class. You can even combine this tool with the emojis you've used previously:

Whatever the tool, getting clear feedback is key to differentiating your instruction and increasing communication with your students!

Exit tickets allow you to breathe for a couple of minutes before your next class period starts.

An exit ticket is like an Instant Pot. You hear about how great it is — it saves time, it’s simple, it’s flexible, and it doesn’t need many ingredients. It seems to be a staple tool at this point, so you pick one up and start using it. So it goes with exit tickets. When we start using them, it may be because of both convenience and necessity. They’re quick and easy, and they allow you to breathe for a couple of minutes before your next class period starts or you need to switch over to the next subject you’re teaching.

Exit tickets also provide a supportive rhythm to your class. They signal to kids that they will be transitioning soon, and this is invaluable to many students — especially if they struggle with change during their school day. Exit tickets provide a natural way to move from one space into the next, figuratively (if students stay in the same classroom) and literally (if students move to a new room). Sometimes that’s as far as we get with using exit tickets. It feels like enough, especially at the start of the school year or in the first year of your teaching career. But we can improve our use of exit tickets by taking them from simple (and valuable!) classroom tools and morphing them into invaluable formative assessments. “The power of exit tickets lies not only in informing instructional decisions — it includes the public acknowledgment of students' ideas and making adaptations of lessons, based on these responses, transparent to students (Marshall 2018). Importantly, exit tickets can also give voice to students who are otherwise silent in class, including English language learners and students "on the margins" of classroom life, and can draw your attention to who is being served in which ways, giving you critical information for shaping your practice to enhance equity and inclusivity.”

What is an exit ticket?