|

Embarking on a journey through project-based mindsets and influences, alongside educators in China.

Our mission seemed somewhat straightforward: a weeklong workshop series for teacher educators in Shanghai focusing on PBL, or project-based learning. Considering the many workshops we have facilitated over the past two decades, ranging from topics such as creating rubrics to analyzing data, running a weeklong workshop in Shanghai on the topic of project-based learning is as fun as it gets!

We have partnered with YouCH, a professional development group in the MinHang section of Shanghai for several years, and have already facilitated workshops for YouCH educators on topics such as teacher research, 21st century learning, and fostering teacher leaders. YouCH, which is a play on words for supporting “youth” throughout the “ouch” of adolescence, is based in China, and our CPET team — Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang, Courtney Brown, G. Faith Little, Dr. Lance Ozier, and me — were all returning to Shanghai and looking forward to working with our YouCH colleagues again. Our plan for the week was solid: participants would work on a meaningful, real-life, weeklong project that would end with a culminating celebration. Mornings would be devoted to working on different aspects of our projects so that teachers could experience project-based learning on their own; in the afternoons, we would zoom out to unpack these experiences by debriefing the scaffolds within our lesson designs and teaching strategies; and finally, participants would have independent planning time. Excited for our workshop and visit to Shanghai, we packed our bags and we were ready to go! Cut to real life, post-pandemic. China had recently relaxed all of its COVID restrictions, resulting in a surge of colds and respiratory illnesses. A day after we arrived, we learned that schools were closing for most of the week due to the fear of spreading illness, and it was too late to reschedule our workshops. The best laid plans… A cultural exchange for educators

Instead of facilitating workshops, we found ourselves engaging in discussions and smaller sessions with our YouCH colleagues, participating in more formal meetings with the principal for Minghin High School, on a visit to the Huang Gongwang High School in HangZhou, and in meetings with professors and education officials in the Shanghai district.

Everywhere we went, we were welcomed warmly with tea and coffee, fruit and treats, and with a genuine love and interest in incorporating PBL into more schools throughout China. At the Teacher Education Centre under the auspices of UNESCO, the director inquired about the possibility of facilitating our PBL workshops in the western, more rural region of China, as a part of the “Rural Revitalization” program for teacher professional learning. They shared with us the belief that social and emotional wellbeing are important aspects of teacher education, as well as creativity — both of which are also key ingredients for project-based learning. At the Institute of General Education Shanghai Academy of Educational Sciences, we were greeted with Starbucks lattes and highlights from the professors’ research and papers on the importance of PBL. The director explained that PBL should not just be a “snack, but the main meal.” They believe curricula should ask real world questions, and students should be able to express themselves creatively as they research and present the possible answers. Again, we were amazed by the enthusiasm for PBL as a method to be included in all schools. Witnessing PBL in Shanghai

We also had the opportunity to meet teachers at a YouCH conference on PBL, and these teachers were already doing project-based learning units. At this full-day conference, we listened as elementary students showcased their PBL artifacts. We were most struck by Steven, a high school student, who shared his project — “Let’s Break the ‘Wall’ Together” — on period shame, which shines a light on the notion that menstruation is normal, yet girls are made to feel ashamed or embarrassed when they menstruate. This project evolved into a fundraising and social awareness project to combat period shame through education, and to raise funds to provide access to sanitary pads in more rural areas of China.

Not only were these students doing PBL, but the topics were open-minded and refreshing! Talking more to the teachers and students throughout the day, we realized that these student presentations were from a class that was dedicated solely to project-based learning In other words, these projects were not woven into their core curricular classes, but completed through an additional class. This is not to diminish the impressiveness of the projects (we were fawning over them!), but to highlight that including project-based learning into the core curriculum is a different endeavor. John Dewey's influence

Over a brunch of steaming dumplings, fish stew, and noodles on one of our final days in Shanghai, we asked Principal Jian from the MinHang section of Shanghai why he was so inspired and committed to PBL. Where did this inspiration come from?

He responded in Chinese, but we heard a name we recognized well in his explanation: John Dewey. The principal reminded us that Dewey spent time in China — two years and two months, the longest amount of time he spent anywhere abroad. Our Chinese colleague proudly recalled how Dewey not only shared his educational philosophy when he was in China from 1919-1921, but how he learned from Chinese culture, and was influenced by Chinese philosophies and practices. What does this mean for our work? Knowing this now, that at the center of the PBL work is a proud connection to Dewey, how might this influence our workshops, if we are given the opportunity to return? John Dewey believed that we must “give the pupils something to do, not something to learn; and the doing is of such a nature as to demand thinking; learning naturally results.” (1916, Democracy and Education). We can’t argue against learning by doing, but what does Dewey’s concept really look like in schools, on a day-to-day basis? Lessons from Maxine Greene

One of our CPET colleagues, Dr. Lance Ozier, reminded us all that our late and brilliant professor at Teachers College, Maxine Greene, was a student of Dewey’s. We were the last generation of students to have had Maxine as a professor, and we briefly swapped stories about her. My closest interaction to her was when my Narrative Research class with Professor Janet Miller visited her at her apartment, since she was 88 years old and no longer traveling to Teachers College. I happened to have my baby, Javier, who was just a few months old at the time, with me at her apartment.

Our class of doctoral students had prepared so many questions for Maxine; we were starting our doctoral research and wrestled with issues over perspective, what it means to be a fair researcher, and hungry for any writing suggestions to avoid being total bores. Maxine listened to our questions and nodded, but really could not stop looking at my baby. “He’s so curious,” she kept saying, “He just can’t get enough of the world!” Here we all were, excitedly trying to absorb as much of Maxine as we could, and here was Maxine, mesmerized by a baby. She was in awe of my baby’s curiosity, a spirit akin to her own. This is the kind of curiosity at the heart of research, teaching, and learning. And at the heart of project-based learning. What I remember most about our afternoon with Maxine is not her answers to our questions (we had so many!), but her authentic curiosity and interest in what was happening in front of her, and on that particular day, that happened to be watching my baby interact with the world by touching and poking at everything in his range. When we return to Shanghai, it is this curiosity that we will have to bring back with us, this curiosity that is at the heart of PBL, and at the heart of Dewey and Maxine Greene’s work. How do we infuse this deep curiosity and learning into our curricula, and our daily lessons? This will be our charge on our return. The realities of PBL

Although we did not have our weeklong workshop series, we did spend one afternoon with 75 teachers from the MinHang School, and gave them a taste of our PBL plans. One of the takeaways from that group of teachers was the importance of teaching students to ask questions, and then using student-generated questions to drive a curriculum. But we also can’t ignore some of the concerns we heard from the teachers, specifically: “PBL sounds like a lot of work, and who is going to support us?” We appreciated the real and honest question, and agree this needs to be ironed out. A new way of curriculum planning requires professional learning and ongoing support from colleagues.

We arrived in Shanghai with a plan to invite teachers to experience and then deconstruct project-based learning. It was a solid plan, but if we return, we may also invite teachers to reflect on the roots of PBL in China, namely, how do you plan with John Dewey’s philosophy in mind? We will keep our workshop practical, but also return to Dewey’s research: What does the constructivist teaching model look like in real life? How can we allow for more discovery for students? The interest in PBL is palatable, as we discovered in formal meetings and informal conversations with our YouCH colleagues. Our colleagues at the Shanghai Academy of Educational Sciences said it best: how do we make project-based learning the meal and not the snack? This is our collective charge.

Empower students to assess their own learning and take charge of their educational experiences.

One of the most exciting things about project-based learning is that it lets students take control of their learning experience, allowing them to lead their educational journey. However, understanding what this truly means and visualizing what it might look like in practice can sometimes feel unclear and ambiguous.

For me, the above means fostering student discovery and embarking on a shared journey with students to achieve specific goals. One way I support teachers with this approach is through collaboratively establishing success criteria with students, rather than dictating them. Moss and Brookhart (2015) advocate for this process, emphasizing the importance of ensuring that students comprehend the learning goals and have a clear understanding of what exemplary work on a project looks like. This ongoing process involves teachers regularly monitoring and assessing students' understanding of learning goals and addressing any misconceptions that may arise.

Empowering student discovery

The significance of success criteria lies in empowering students to assess their own learning and take charge of their educational experiences, fostering a sense of self-efficacy. Students who believe in their ability to succeed are more likely to persist in their work, even in the face of challenges (Bandura, 1997). In essence, success criteria become a means to provide students with an opportunity to actively drive their own learning. Teachers play a significant role in this process by posing essential questions such as: What do I want my students to learn? How will I teach it? How will I know they got it? Similarly, students are encouraged to inquire about their own learning: What will I learn? How will I learn it? How will I know that I got it? When it comes to communicating success criteria, we can tell students explicitly, show them through modeling, offer examples, or support them in discovering the criteria themselves, whereby students are actively exploring, uncovering, and understanding concepts or knowledge on their own. Student discovery leads to deeper understanding, greater intrinsic motivation, longer retention of knowledge and skills, as well as promoting student ownership over their learning. To facilitate this discovery, I want to share four promising practices.

Promising Practice: Questioning

Engage students in questioning to ensure a deep understanding of project goals. Techniques such as putting learning targets in their own words, Think-Pair-Share, and an iteration of KWL (what we know, want to know, what we will need, what learning/skills we can lean on) can be effective. An example of series of teacher-facilitated questions as part of a project on the water cycle could sound like:

Promising Practice: Envisioning

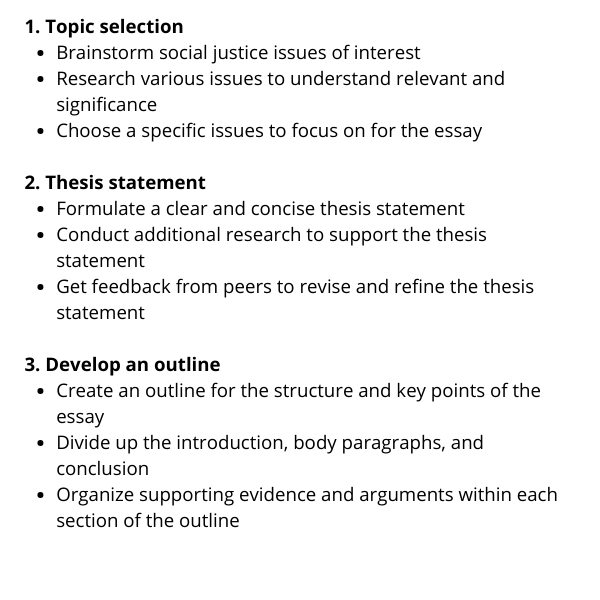

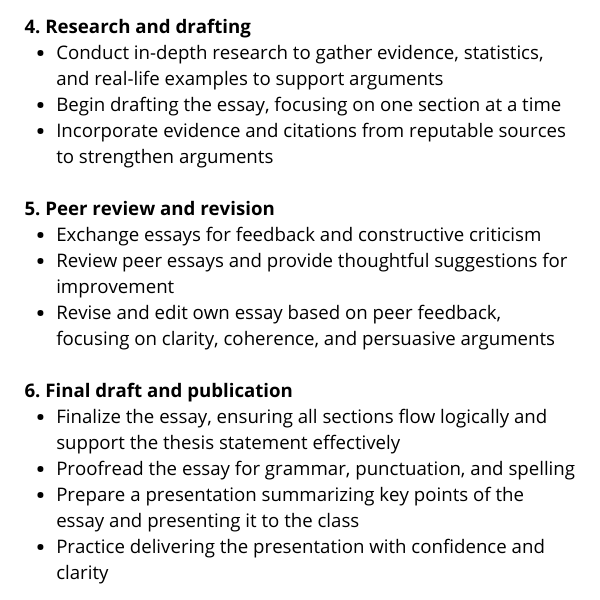

Support students in visualizing their goals and the final project outcome. Creating planning charts, breaking down tasks into smaller parts, and involving teachers in the planning process can enhance students' understanding and success. Here is an example of a student-created planning chart for a high school social justice project:

Promising Practice: Using exemplars

Expose students to examples of past work, encouraging them to analyze and describe its traits, features, and styles. This inductive approach allows students to discover project expectations through inquiry and exploration, promoting a deeper understanding. This could look like:

Promising Practice: Rubrics

Utilize rubrics not just for evaluation, but as a guiding tool throughout the project. Students can assess examples, rephrase or recreate rubrics in their own words, and use them to evaluate their own work and that of their peers, informing revisions. An example of this could look like:

The journey toward student-driven project-based learning is marked by the collaborative establishment of success criteria, enabling students to actively participate in their own learning. By implementing these promising practices, educators can create an environment where students not only understand the goals, but also take ownership of their educational path, ultimately promoting continuous growth and exploration.

Offer students the essence of project-based learning, within a condensed timeline.

“I’d love to do project-based learning, but there just isn’t enough time.”

I hear teachers say this all the time and it's understandable. Between the pressure to “cover all of the content,” days of instruction lost for testing, unexpected snow days and power outages, the uncertainty of student attendance, and uncertain access to computers and other technology — project-based learning (PBL) can feel like a logistically impossible feat. With that said, the concept of project-based learning appeals to many teachers, especially those who have used it with success in the past. The Buck Institute describes project-based learning as “[a] teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by working together for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an authentic, engaging, and complex question, problem or challenge.” When students respond to authentic challenges, we often see an increase in student agency and engagement. Students embrace the process to respond to a problem or challenge that affects them directly or indirectly, striving to acquire skills not out of a desire to pass a test, but rather to achieve a self-determined solution to a problem that will have a greater audience and impact outside of the classroom.

Condensing your timeline

In the Buck Institute’s description of project-based learning, they describe it as an approach that requires “an extended period of time to investigate and respond.” For teachers who are confident and able, project-based learning might take shape as a complete redesign of their units, allowing for 4-6 weeks of extended time to research as part of an ongoing investigation. For teachers who feel like an entire unit of project-based learning might be impossible right now, the models I share below show what a project-based approach might look like in a more condensed timeline. These are not prescriptive, but rather imaginative, illustrating how just one 40-minute class period that follows a workshop model (with a mini-lesson) could be approached with the spirit of inquiry. At its core, I suggest that a project-based learning approach asks students to take on the roles of problem-solver, investigator, collaborator, and innovator. Let's imagine a project in which students are asked to develop a school policy around the use of artificial intelligence — what can that look like in one unit, one week, or even one class period?

One unit

Week 1

Week 2

Week 3

Week 4

Week 5

Week 1

Students start with a real-world problem or issue that is far away or close to home with a real-world audience.

Week 2

Students research potential solutions and/or gather relevant information.

Week 3

Students research potential solutions and/or gather relevant information, collaborating with others.

Week 4

Students synthesize their findings and create some demonstrations of their solutions, written and/or multimodal.

Week 5

Students present or share their findings with others, gathering feedback and revising.

One week

Monday

Tuesday

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

Monday

Students start with a real-world problem or issue that is far away or close to home.

Tuesday

Students research potential solutions and/or gather relevant information.

Wednesday

Students research potential solutions and/or gather relevant information, collaborating with others.

Thursday

Students synthesize their findings and create some demonstrations of their solutions.

Friday

Students present or share their findings with others, gathering feedback and revising.

One lesson

Do Now

Mini-Lesson

Guided Practice

Independent Practice

Exit Ticket

Do Now

(5 minutes)

Students start with a real-world problem or issue that is far away or close to home.

Mini-Lesson

(5 minutes)

Students acquire background information on the issue.

Guided Practice

(10 minutes)

Students deepen their understanding of the issue by reading a credible source.

Independent Practice

(15 minutes)

Students collaboratively write a short solution.

Exit Ticket

(5 minutes)

Students present or share their findings with others, gathering feedback and revising.

Takeaways

As an approach, project-based learning empowers students to be agents of change, capable of gathering and synthesizing information, creating solutions, and sharing their findings with others. The more time that students function in our classrooms as these agents of change, the better. Why? Because the real-world is full of problems and, as teachers, we are empowering young people to be confident that they can envision impactful solutions. Whether you embrace the spirit of PBL in a comprehensive unit, a week, or even just a single lesson, you are contributing to the growth of a new generation of change-makers — and there’s always enough time to get started.

Strengthen the connection between the why and how of student learning, cultivating essential 21st century skills along the way.

In a recent conversation with leadership at a school district in Westchester, NY, I posed the question: What do we recognize as the purpose of education, and what is it we want and hope for our students when they graduate? My intention in asking this was to encourage leadership to explore whether the goals and values they have for their students are reflected in their current efforts, including their curriculum, instruction, and initiatives. Put frankly, I was asking leadership for their thoughts around what they were doing, and if they thought it was best preparing students for the 21st century.

After some lengthy discussion and a deep dive into their curricular maps, it was revealed they had work to do. Despite their good intentions, they were still operating from old-fashioned and insufficient pedagogies. Unfortunately, through our research and experiences, we’ve found this is the case with most schools today. A look back through history can help underscore this point.

Education for what?

In the 19th century, the purpose of education and schooling was to prepare students for work. There was one schoolhouse, and one teacher for many students, all of whom sat in rows. Instruction was focused on repeating, reciting, and reproducing — all skills necessary for work, which was predominantly in factories. In the 20th century, things evolved, thanks to the introduction of basic technology like the typewriter. Schooling focused on teaching students to apply information provided by a teacher or by a resource, like textbooks. Like the 19th century, there was a strong connection between school and work, though the necessary skills shifted to accommodate work in an office, and revolved around application and analysis. Now, about a quarter into the 21st century, we are faced with a problem we’ve yet to experience. It’s the first time in history we are presented with a disconnect between what and how we are teaching, and the realities of a 21st century world, where technology continues to change and shape our experiences. Organizations today are seeking innovative and imaginative individuals, yet students are still looking to the teacher to provide the answers, and there is little to no opportunity for students to engage in critical and creative thinking, or individual and collaborative problem-solving. Our needs and goals as a society are evolving but sadly, most of our schooling is not. As my colleague Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang says: We can’t use a 20th century pedagogy in a 21st century world. How can we adapt to 21st century work and support students in acquiring skills that we know will serve them in the 21st century and beyond?

The promise of project-based learning

One of the most powerful ways to advance the skills and capacities necessary for students to thrive in today’s society is through project-based learning (PBL). PBL supports the development of fundamental skills such as reading and writing, as well as 21st century skills like research, collaboration and communication, problem-solving, time management, and the use of technology. In short, PBL sparks curiosity and curiosity leads to innovation. What is PBL? As the Buck Institute states, project-based learning is “A teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by working together for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an authentic, engaging, and complex question, problem or challenge.” They also offer a distinction between “dessert” projects and “main course” projects that is particularly helpful — a dessert project is “a short, intellectually-light project served up after the teacher covers the content of a unit in the usual way” whereby a “main course project is when the project is the unit.” When it comes to CPET’s approach to project-based learning, we very much lean on the expertise of the Buck Institute. We believe projects:

Imagining project possibilities

How might teachers and students begin this work? Start with a real-world problem far away Projects that are focused on a global issue help students demonstrate understanding of a problem that occurs in the world, even if it isn’t directly about them. Students can explore the features of this problem, how it impacts the people, as well as the far-reaching implications and solutions!

Start with a real-world problem close to home This type of project can help students demonstrate understanding of a problem that occurs in their specific context. Identifying a problem locally engages people intimately and can inspire calls to action that are more likely to be carried out. The goals would be to understand a situation, issue, or a series of events that happen in multiple contexts around the world and ideally consider the global connections across diverse communities.

Meditate on a word, concept or theme Words are powerful, and making use of “academic” vocabulary or transferring knowledge from one domain to another are two areas where schools struggle to build students’ capacity. A project on a general word, concept, or theme is engaging and develops these important skills across content areas.

Our students have the potential to do amazing things. They just need the right conditions to survive and thrive. Project-based learning promotes the acquisition of real and relevant skills of the 21st century by asking questions, exploring issues that matter, and imagining possibilities for positive change. PBL is now the focus of my work with the district in Westchester, and I’m really excited by the progress they’ve made. I invite you to use any of these practices to support the creation of your own project, and if you need more help, we are here!

Three entry points for designing project-based, student-centered instruction.

With the amount of interruptions and disruptions to learning over the last few years, many schools and teachers are faced with the reality that their curricula and instruction may no longer be relevant or appropriate, given all of the learning that’s been missed. As a result, teachers are wondering how to best revive their curricula to make it more reflective and responsive to their students’ needs. Furthermore, they are concerned with how to best promote and maintain engagement of their students, and incorporate fun into their learning.

Project-based learning can be a powerful solution. Projects promote high levels of student engagement while also supporting the acquisition of academic skills and content knowledge, and also real-world, 21st century capacities and characteristics, including: critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, and caring. Project-based learning puts students at the center, and are often inspired by real-world, community-based issues that matter to students, providing safe spaces for them to engage in meaningful reflection, and share their unique perspectives with the world. How can we make our instruction more project-based? Where do we start? Many teachers I work with are eager and excited to transition to project-based learning, but struggle with knowing how to begin. Their excitement is often met with fear and apprehension as they feel bound to a certain curricula or scope and sequence. Use the three considerations below to imagine the first steps you might take in creating more student-centered, project-based instruction.

Consider: Student voice and choice

One of the core principles of project-based learning is student choice. As teachers, we want to be thinking about where and how students can make decisions about their own learning. But this doesn’t have to be overwhelming — we can offer students choice within manageable parameters. A simple starting point can be to think about choice when it comes to topics, texts, or tasks. For example, if we know that students need to write a persuasive essay as one of our grade level or content area requirements, allow them choice in the topic they write about, or the texts they read as part of the process. Or, if we know that students need to read a certain text as part of a course, then allow them choice when it comes to the task of how they will share their learning (e.g. presentation, podcast, etc.).

Consider: An authentic audience

Another core principle of project-based learning is an authentic audience. Traditionally, the audience for student learning is the teacher, or maybe their peers. But how can we challenge this tradition and provide students with opportunities to write for a more real-world audience? The ability to communicate with specific audiences is an incredibly important skill, and something that will serve them beyond the classroom. When it comes to identifying an audience, we can use questions such as: “Who would benefit most from learning about this topic or reading this work?” Identifying an audience from the start, prior to launching into a unit, can support students in writing with this audience in mind, which should inform their tone, their language, and their vocabulary. But it doesn’t stop there — think about how your students can authentically connect with their audience, whether it’s through inviting them to a reading or celebration, posting their writing online, or even sending representations of their work in the mail.

Consider: A larger purpose

In line with thinking about an authentic audience, is connecting student efforts to a larger purpose. Most often, the purpose of student work is for a grade, or to pass a class. Projects, in contrast, have a deeper purpose that connects to the world outside the classroom, which can make them more meaningful and enjoyable for students. Whereas we might talk about the traditional purposes of student work as being to persuade, entertain or teach, identifying a more specific purpose can strengthen students' skills as writers and communicators. For example, a purpose could be to call someone to action to resolve a community issue, to share advice, or to challenge perspectives. Being more specific and deliberate with the purpose can help inform and inspire how students understand their efforts.

These three considerations reflect just some of the essential principles of project-based learning, and are a great place to start if you’re looking for manageable entry points to this type of work. These project elements can serve to inform extensions and/or revisions that you make to existing curricula, without it feeling overwhelming or impossible, and most importantly, help revive your curricula to make it more student-centered and student-driven.

One school's success with unpacking the COVID crisis through project-based learning.

Educators are our superheroes, not because they can swoop in and solve all the big problems, but because they create spaces for students to explore and discuss real issues and pose real solutions. When we offer students the opportunity to engage deeply in meaningful, relevant problems, we can build student confidence and offer them agency over potentially frightening issues.

When our society seems rife with complex problems, it’s the perfect time to introduce problem-based projects. But before we look at an example of a problem-based project, let’s look to the roots of project-based learning to deepen our understanding of its principles. Problem-based learning can be linked to R. C. Snyder’s “Hope Theory” which promotes agency and hope — crucial concepts, especially for our students during a time of societal upheaval. The positive psychology behind “Hope Theory” is: “simply put, hopeful thought reflects the belief that one can find pathways to desired goals and become motivated to use those pathways.” Of course, this speaks to one of the goals of problem-based learning for students, which is to develop, practice, and apply key skills to real-world issues. When we get more ambitious, these problem-based projects may even expand across disciplines and become interdisciplinary projects! Elementary school teachers often do a great job of working across subjects in their own classrooms, but for middle and high school, where subjects are generally taught discreetly by separate expert teachers, implementing projects across disciplines may seem more daunting. It can sound complicated, but as our classrooms increasingly shift to online learning spaces, classroom walls and clearly delineated class periods are no longer barriers, offering us opportunities to work more easily with our colleagues across classrooms and disciplines.

Implementing a schoolwide interdisciplinary project

As an instructional coach and teacher, I understand just how complicated planning for blended learning can be; however, I have been inspired by how educators have used the blended and remote learning spaces as an opportunity to innovate, develop, and implement projects. As we moved into remote learning during the early phases of the COVID-19 crisis, I was working as an instructional coach with the Academy for Computer Engineering and Innovation 2 (AECI2) as it started up its first/founding year as a high school in the Bronx. While the energetic, innovative teachers and principal always gave their all to the students, nobody envisioned that by the end of the school year, we would actually collaborate remotely to create and implement the Living History Project — a remote, school-wide interdisciplinary project that culminated in a call to action letter writing campaign and a community-wide presentation. As the initial months of online learning continued and COVID-19 began to seriously impact our community, we realized that our students needed productive ways to synthesize and make sense of what it meant to be living history. Recently, I met with two of AECI2’s lead teachers, who initiated and coordinated this interdisciplinary project — Chris Mastrocola, an AECI2 English teacher and the school’s technology expert, and Joyce Brandon, the 9th grade math teacher. They offered some valuable insights and tips into successfully developing and implementing interdisciplinary projects, which can be a helpful starting point for developing your own project. Please note that these steps do not need to be followed in order. Different starting points work better for different contexts and communities.

Collaboration & communication are key

To coordinate all pieces of an interdisciplinary project, Chris suggests establishing regular planning meetings, and making sure that one teacher from each discipline joins an interdisciplinary planning team to meet and work on the project. As our project progressed, weekly meetings focused on different topics relevant to each stage of the project. Regular meetings are not only important when first starting a project, but help keep it moving at each stage of the process. Based on our experiences, here are Chris’s suggestions:

Choosing a problem-based topic

How do we choose topics for projects? Do teachers or students drive that decision? Or, do project topics naturally reveal themselves? I’ve found that the most productive projects are those that arise as authentically as possible, driven by a current, complex societal problem. We generally know a topic is worth investigating when our students show an interest in it and are posing genuine questions about the issue. At AECI2, the challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic and the necessity for coherent local and federal governmental responses were the problems that naturally drove and inspired our project. Students were concerned about the impact of COVID-19 on their own lives and the lives of others. Living in quarantine and practicing social distancing, they were raising questions with teachers about the impact of the disease, how to manage it societally, and also how to cure it. This pointed us to a natural focus for our project. Joyce reminds us that when choosing a topic to explore, we need to be aware of how the students may experience it. For example, at the time when the students started the Living History Project about the COVID-19 pandemic, they were living in a community with the highest numbers of cases and deaths from the disease in the United States. Joyce points out that when we are living among the numbers, we need to be sensitive to the trauma or hopelessness that students may be feeling. Moreover, when our students are members of a community that is disproportionately impacted by an issue, or has historically been marginalized, we want to make sure that the chosen topic or project isn't accentuating students’ sense of hopelessness or powerlessness. Rather, through research and knowledge-building and a call to action approach, we believe in the power of project-based learning as a way to offer students a sense of agency and empowerment.

Defining essential questions

Collectively, we developed essential questions about the problem of COVID-19 to drive our project. Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe, the authors of Understanding by Design explain that essential questions are “not answerable with finality in a brief sentence.” Their aim is to stimulate thought, to provoke inquiry, and spark more questions. They are “broad, full of transfer possibilities” and “cause genuine and relevant inquiry into the big ideas and core content.” Essential questions can help the teacher maintain a focus on the goals of the unit or project, and also stimulate inquiry, discovery, and meaningful connections for students. Here are the Living History Project’s problem and essential questions that we developed: Essential question:

Guiding questions:

Project assignment prompt:

Student responses to each of these recommendations were informed by their explorations in social studies, math and science classes, and written in their ELA classes.

Defining project goals

A major goal of this project was for students to synthesize and apply their research and learning from math, science, and social studies into a coherent set of recommendations about how to address the COVID-19 crisis. We also wanted students to feel empowered and have some agency over an overwhelming situation that was affecting their own community and lives. As you work to establish your own project goals, consider which key standards will be assessed by the project. In this case, we knew that literacy across science, social studies, English, and even math all incorporate argument writing and skills. Each subject teacher identified the key standards addressed in the project.

Backwards planning to teach key skills

Chris and Joyce both attest to the importance of breaking the final assessment product into parts in order to create a plan and teach all necessary skills. Joyce quickly realized that in her Algebra classes, students needed to really be taught to read and analyze data in charts and graphs, and at the same time, they were learning these skills with a heightened sense of importance as they applied their findings to their recommendations for addressing the COVID crisis. Joyce also cautions that percentages are hard to understand — students, and many adults, can't really conceptualize such large numbers, such as the number of people testing positive for COVID, so she began to use comparisons and analogies that were more accessible to students. The English teachers at AECI2 recognized that students could use some instruction on letter writing, as well as time to revise and edit their letters. So, we decided that the students would organize, revise, and edit their final letters in their English lessons as a final phase of the project. In social studies, Brett Pastore reviewed a range of documents and images with students, highlighting epidemics throughout the ages, including the Black Plague and the 1918 influenza epidemic. From analysis of these documents, students made connections to the COVID-19 pandemic and drew conclusions about how to address the current situation. And in her Living Environment class, Samantha Cunningham developed a series of lessons for students to learn to analyze data about the health impacts of COVID-19. Finally, the project was handed to the school’s technology teacher who designed lessons to support students in the final phase of the project, as they formatted and uploaded their projects to Padlet.

Backwards planning for each subject

This project expanded across the disciplines as, together, teachers identified how students would complete components of the project in their classes as they worked toward their final product — the call to action letter. Teachers identified the key skills and steps for their subject areas, and developed a sequence of lessons through backwards planning from the final product. To incorporate the students’ investigations and learnings about the pandemic from across disciplines, we decided to ask each student to contribute a paragraph with specific recommendations, using data and evidence from each of their subjects — Algebra, Living Environment, and Global History. They would then craft and revise their letters in their English classes, applying all the components of argument writing that they had studied. Students also made connections between subjects — for example, in math, students referenced what they know about pandemics throughout history to make sense of questions such as do these numbers make sense?, and how are these data related to the data from earlier epidemics?

Outline a final assessment product

Our final product was a call to action letter, addressed to a politician and offering three recommendations on how to address the COVID-19 crisis. The final presentation was presented on Padlet. All students published their final project with the following components:

Plan for presentation/publication of the product

For this project, we relied on platforms that AECI2 teachers were already using — Google Docs for teachers’ planning, and Google Classroom for interacting with students. Building on familiar systems that are already in use is helpful for any project, especially one with this level of interdisciplinary collaboration. To present their work to teachers and peers, students first created a presentation using Google Slides, with a slide for each of the following components:

Students also included artwork and excerpts from their journal entries about the pandemic, and uploaded their final presentations to Padlet, where it could be shared with the school community for feedback and comments. At AECI2, we decided to use Padlet as our publication platform, since each student could easily add their own post to a school-wide wall, and other students could easily comment on it. With more time, we could have expanded this opportunity and supported students in filming their presentations using Screencast-o-matic or something similar, which would allow for more connection between members of the community.

Benefits of problem-based projects

Here are some of the benefits of problem-based projects that we encountered with our partners at AECI2:

Problems in society can drive authentic projects, providing students with relevant topics that can build their confidence, allowing them to feel they have more agency over potentially frightening issues, and offering them an opportunity to pose solutions to real issues that are impacting their communities.

Our experiences with planning and implementing AECI2’s Living History Project not only showed us the benefits of problem-based learning, but how exciting it is to work across disciplines. We were able to increase interdisciplinary collaboration and work free from traditional educational barriers, such as time and space, as all teaching and learning was happening remotely. In our new educational spheres, the constraints of in-person teaching no longer exist in the same way, providing a gateway for exciting and engaging work with our students. The opportunities are endless.

Incorporate PBL into existing tasks and create engaging, meaningful opportunities for your students.

Project-based learning is a widely used term in education. Although many educators have a general understanding of what it means, it’s often met with uncertainty and apprehension.

A simple Google Search of “project-based learning” results in 10 pages of articles or blogs, written by various organizations, institutions, and individuals. For instance, cultofpedagogy describes project-based learning as a combination of standards, best practices of UBD (understanding by design), and formative assessments. ASCD describes a project as meaningful if it fulfills two criteria: that students "feel the work is personally meaningful, as a task that matters" and that the project fulfills a “meaningful purpose.” Edutopia describes project-based learning as learning that tells a story. Throughout my 15 years of teaching and coaching, I’ve seen varying interpretations and implementations of project-based learning myself, which have been further complicated by the move to remote and blended learning environments. For educators who are working with packaged curricula, it can be especially difficult to see the opportunities available for introducing PBL in classrooms. But focusing on the core components of this work can support us in establishing engaging, meaningful, and doable project-based learning experiences for our students.

Components of project-based learning

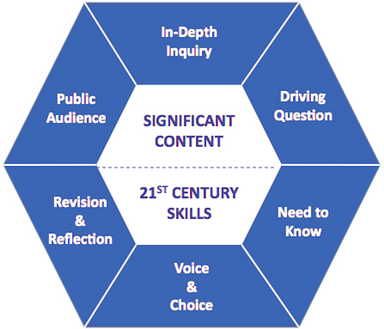

One of the most well-known and admired institutions when it comes to project-based learning is the Buck Institute. They offer what I think are very helpful criteria to inform what project-based learning can look like:

In line with much of the graphic, our K-12 coaching team believes that projects are a wonderful way to help students cultivate 21st century skills, focus on a pressing topic or issue, develop their identity as readers and writers, and engage in a writing process that involves extensive feedback, revision, and reflection on their learning. We believe the pedagogy of project-based learning is about:

Now that we’ve laid out some of the basics, we can investigate what project-based learning might look like in action. The questions above can help inspire task revision and allow you to incorporate project-based learning into pre-packaged curricula, without starting from scratch.

Creating relevant, meaningful tasks

Recently, I partnered with a school in Brooklyn to support them as they designed and reimagined assessments for online learning. As an elementary school, they had adopted a packaged curricula for English Language Arts instruction. My goal was to help them make existing tasks and assessments more engaging and relevant for students, and support them in redesigning the tasks as they were written in order to infuse elements of project-based learning — without compromising rigor. We began with a first grade writing task that focused on persuasive reviews based on favorite places, foods, etc. To begin revising this task, we started by examining three important questions, informed and inspired by the Buck Institute:

We used these questions to guide our analysis and revision, referring back to the original task:

Turning the task into a project

Now that we have been able to identify the basic possibilities and challenges with this task, we can continue on to revision, and begin to shift our original task into a project. When it comes to developing authentic and meaningful projects, we like to turn to a promising practice called GRASPS. This stands for: G: What is the goal of the project? R : What is the role of the student? A: Who is the audience? S: What is the structure of the writing? P: What is the purpose? In conjunction with our earlier questions, the GRASPS framework is a helpful tool in redesigning tasks and ensures that our revisions are clear. In our example, the responses look something like this:

Equipped with these revisions, we can now more easily shift the original writing task to one that is project-based, and understand how we can introduce these ideas to students. This not only generates excitement for students, but teachers as well — our partners in Brooklyn were eager to plan and implement this project within their classrooms, and were excited about the additional possibilities for creativity.

What I hope is evident throughout this process is that project-based learning can have a variety of entry points — whether you’re teaching remotely or in-person, creating your own projects, or reimagining pre-packaged curricula. Regardless of your situation, recognizing how instruction can be meaningful, relevant, and doable — even with the current parameters of teaching and learning — is possible.

Offer your students an opportunity to solve real world problems, demonstrate critical thinking skills, and collaborate with their peers.

Problems. There’s no shortage of them these days — the pandemic has spurred countless challenges and intense despair; there are too many to list. Teaching during the pandemic has been a challenge in and of itself, as we are always looking for ways for students to be engaged with curricula and drive their learning, and that’s hard to do whether we’re teaching in person or remotely.

If you think back to your college or grad school days, you may recall the constructivist thinkers, such as Jean Piaget, who believed that students learn best when they construct their own learning. Problem- and project-based learning offers teachers an opportunity to do just that — instead of telling students the answers, you can create a learning environment in which students learn through discovery, thinking, tinkering, reflecting, and developing answers on their own. We may already be familiar with ways that we can bring this type of learning to in-person classrooms, but it can also be delivered to students who are learning in remote or blended environments.

Problem-based learning vs. project-based learning

Project-based learning is situated in real-life learning. The Buck Institute for Education defines project-based learning as a “teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an authentic, engaging, and complex question, problem or challenge.” If you ever walk into a classroom and see students working on a project with an exciting buzz in the room, chances are, their teachers have designed a project-based learning task. In our own lives, we know that when working on a project, we often discover a problem we didn’t realize we had — but once it surfaces, it demands a solution. (Remember those early pandemic days when we were acclimating to teaching remotely, but also trying to solve the problem of having no dedicated teaching space at home?) In teaching, this idea rings true, too. As we are learning more about a topic, we may discover a problem alongside our students, and this is the breeding ground for an exciting new project. This is the foundation of problem-based learning. Problem-based learning also offers students real-life learning opportunities, as well as the chance “to think creatively and bring their knowledge to bear in unique ways” (2020 Schunk, p. 64). Problem-based learning can look differently depending on the content and grade level, but often includes group discussions that allow for multiple perspectives on a topic, a simulated situation that involves role playing, or group work that includes both collaborative work and time to complete tasks individually. Problem-based learning promotes autonomous learning, self-assessment skills, planning time, project work, and oral and written expression skills. According to a July 2020 article from the Hechinger Report, problem-based learning has gained tremendous momentum, because it allows students to work more freely and at their own pace — a key advantage when learning remotely. In problem-based learning, the content and skills are organized around problems, rather than as a hierarchical list of topics. It’s also inherently learner-centered because the learner actively creates their own knowledge as they attempt to solve the problem.

Putting the “Problem” into Practice

As former English teachers, we both understand the challenge of putting new professional learning into practice. For teachers who need a refresher on how to design a problem-based learning experience for their students, Problem Based Learning: Six Steps to Design, Implement and Assess breaks down the steps to move PBL into practice as follows:

To help put these problem-based steps into perspective, we can look to our recent work with partners from a high school in the South Bronx. The chemistry team there decided to use an anti-racist lens while addressing a problem that was very real to their students — fireworks. During the summer of 2020, there was a record number of firework incidents in New York City. According to an article in the New York Times, the city received over 1,700 fireworks complaints in the first half of June alone. Our partners used this problem as an opportunity for students to research fireworks from multiple lenses, and imagine how they might present their findings and recommendations to local officials. After all, shouldn’t New York Governor Andrew Cuomo hear from high school students in the Bronx about the effects fireworks have on their communities? Here’s what the framework might look like in this example:

From here, we can imagine the possibilities for this framework, considering how students might address the underlying problem from different perspectives and content areas:

Teaching and learning throughout a global pandemic has presented more than its share of challenges. Out of necessity, tremendous innovation has taken place with the use of technology, pedagogy, and curriculum. With problem-based learning, we can continue this innovation in our classrooms, offering our students opportunities to solve real world problems, demonstrate critical thinking, and collaborate with their peers. We would love to hear what problem-based learning tasks you are designing for your classrooms!

Writing for publication can create awareness, raise social consciousness, and provide students with essential life skills.

When a student writes for publication, there is a shift in the dynamic between the student and their work. Picture yourself asking a student whether or not they spent a significant amount of time on their writing, only to have them respond, “Why would I spend time on it? It’s just for you.” In contrast, consider a student, who previously considered himself anonymous, telling his teacher, “Mr. Nick, I’m famous now!” after the book he co-authored with his classmates was published. Two very different reactions to a writing experience. How do we understand these two contrasting responses from young writers?

Founded in 2002, the Student Press Initiative (SPI) was designed to develop, foster, and promote writing across the curriculum through student publication, and revolutionize education by advancing teacher leadership in reading and writing instruction. Students transition from “writing for their teacher” to writing for an audience of their choice. To date, SPI has published over 850 books representing the original writing of over 12,000 students. SPI’s core values — project-based instruction, real-world authorship, community of learners, and celebrating student voice — resonate throughout these books. The grounding of these values raise the bar for what, how, and why students write.

Project-based instruction

We believe in using publishing for a real-world audience as a means to design and shape curriculum and expectations, as well as promote student engagement. We employ a backwards-planning model, where a final product is used to form an infrastructure for classroom instruction and activities. Through inquiry of the specific requirements and expectations of each project, teachers and students can better articulate the behaviors, artifacts, and customs necessary for the successful completion of the project — and being that publishing a book is a shared experience, students work together to support and encourage one another in new and powerful ways. Publication projects help to shape the culture, rituals, and routines that take place in the classroom. At the start of a project, a large calendar often overtakes the walls of a classroom, and teachers and students work together to identify the genre, audience, and purpose of their project, as well as establish details and deadlines. This helps establish a strong sense of community and collaboration. This is project-based learning at its best!

Real-world authorship

Real-world authorship shapes our approach to teaching and learning. Whether the audience is a class of incoming freshmen or first-year teachers in training, we work to connect young writers with actual readers. In the SPI model, classrooms become publishing houses in which teachers and students collectively shape an editorial vision. By exploring questions, issues, or concerns that exist in the world, their community, or within a specific content area, teachers and students collaborate to define a meaningful genre, theme, and audience. Writers then work to understand the expectations of their audience as they craft pieces with real readers in mind. No matter the content, there is always a real-world model that can demonstrate student learning with panache and voice that will engage readers. Through participation in a publication project, students develop skills and processes similar to those of professional authors. Students are supported through pre-writing and a gathering of ideas, drafting while consistently revising and editing, and finally, publishing, where they format and polish their writing to prepare for publication. Students experience “real” expectations and deadlines for publishing their book. Through these experiences, a strong sense of excitement, energy and urgency emerges.

Community of learners

SPI challenges traditional notions of “experts” in the classroom. Inspired by the work of Lave and Wenger (1996) and what they call “communities of practice,” we aim to cultivate students’ sense of expertise as writers by engaging in processes such as thoughtful inquiry of mentor texts, peer review, and peer editing. Through such processes, teachers and students work to establish a community of writers, consisting of many experts and many resources for learning and growing as authors. We encourage teachers and students to engage with a variety of texts as they begin to define qualities and attributes of powerful writing. As students learn the skills needed to write successfully, they also become experts in the project’s central theme as they read mentor texts, break genres down into smaller components, and ultimately, craft pieces that represent their learning and culminate in a final publication. A project designed around an in-depth genre study and inquiry invites students into a shared experience, and allows teachers to craft a thoughtful curriculum that addresses specific content and skills.

Celebrating student voice

Every student has a unique voice. Rather than celebrate the work of select students, we aim to celebrate the work of all students, using publication and celebration as a way to leverage and encourage participation. We believe every project should culminate in celebration — whether teachers and students decide to host a large-scale public reading at a local bookstore, smaller readings at locations such as their own school auditorium or classroom, or virtually with classmates, families, and friends. Celebrations — no matter their size or format — are powerful and rewarding experiences, and allow students to proudly share their writing with their community.

Writing can serve as a tool for creating awareness, raising social consciousness, and providing students with essential life skills. Our core values change the perspective and perception of writing for students around the world. These values, deeply embedded in our publications, reflect best practices for teaching writing in the 21st century, and help prepare students to succeed in lifelong learning.

To learn how you can partner with the Student Press Initiative and bring your students' writing to life, please reach out to us here.

Give students the chance to move — intellectually, physically and emotionally — into the world of a text.

We begin our session with an exercise borrowed from Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, Massachusetts. Players (our term for students and teachers who are in creative collaboration with each other) disperse throughout the room facing in any direction and are invited to move silently about the room at their own pace without collision, always passing through the center of the room en route to another side (rather than merely circling the periphery). Welcome to the act of milling and seething.

The purpose of this introductory activity is twofold: first, to foster an awareness of space. All too often in school, students are aware of neither the classroom as a physical space nor themselves and their peers as bodies coexisting within that space. Milling and seething prompts students to examine the entirety of the classroom space; at points, the facilitator leading the activity claps and says, “Look around. Are there any empty places in the room? When I clap again, move to fill them.” Students thus begin to notice the gaps and spaces within the room at any given time and to understand their responsibility to venture out and fill those gaps and spaces. And because of the mandate that they move through the center of the room as they mill and seethe, students must negotiate encounters with one another. They must become aware of where their individual bodies end and the bodies of others begin. Second, to ease players into imaginative work without any burden of “performance.” There exists no audience in this exercise; all are players. Players need only follow the directions of the facilitator (“When I clap, pause wherever you are. When I clap again, begin moving.”), and these directions shift subtly as the exercise progresses. While at first, the facilitator might ask players to “speed up (or slow down) by 50%, whatever that means to you,” directions ultimately become more like this one: “Pause. You have somewhere important to be. You’re late. When I clap again, get there.” Even with this simple direction, the players start to move into imaginative worlds.

Reimagining texts and teaching

The Literacy Unbound initiative, the driving force behind this session, was originally conceived as a grand experiment in teacher education that sought to encourage instructors to consider the power of artistic play as an opportunity to help students develop as critical, collaborative, creative readers. At its core, Literacy Unbound seeks to reinvigorate students and teachers through project-based, collaborative curricula developed around challenging texts. Throughout this process, we often witness increased student engagement and the development of a stronger classroom community. By bringing students and teachers together as creative collaborators, we’re able to reimagine the acts of reading, writing, listening, and speaking through multiple modalities. Though various aspects of this process can change, the core principles always remain the same:

Why does this work?

Through this approach, students get the chance to move — intellectually, physically and emotionally — into the world of the text. So frequently, we talk about text in the classroom. By contrast, our process allows students to talk from within the text; they speak directly from the perspective of one character and then another. They can feel the story in ways that might not otherwise be possible. At Literacy Unbound, we believe strongly that rich meaning-making happens when we find ways to experience literature together in the classroom.

Support students in establishing their voices as writers while advancing teacher leadership in reading and writing instruction.

Student writing is often read by one person (a teacher), and for one reason (a grade). But what if it could be different?

Through our Student Press Initiative, we seek to engage students in writing projects that culminate in print-based publications. These publications are designed for specific audiences, shaped around specific genres, and become widely accessible to their school community and the general public. This process not only helps students to establish their voices as writers, but helps revolutionize education by advancing teacher leadership in reading and writing instruction.

Raising the bar for student writing

Though each publication is a unique reflection of its student authors, the five phases of our publication process remain constant:

Publication in action: personal narratives from the Bronx

This spring, we supported 9th and 10th grade Special Education students at the Bronx High School for Business (BHSB) through this process. Their teacher was eager to introduce a project that would provide her students the opportunity to share a meaningful experience through the writing of a personal narrative or poem. With this in mind, our coaches worked alongside the teacher and her students to facilitate a conversation about the audience for their project. We asked questions such as:

After careful consideration and deliberation, these young authors felt strongly that they wanted to write to younger members of the Bronx Business community — primarily incoming students and siblings — in an effort to offer meaningful advice. Over the course of the project, students at BHSB were able to hone and refine their writing, particularly as it relates to communicating with their chosen audience. They were able to revise their writing to include more colloquial language and tone, which they recognized would be most effective for communicating with their young and familiar audience. As a result, they published The Barriers We Faced, The Bridges We Built. This collection highlights the obstacles many BHSB students have encountered — moving to a new country, struggling in school, and disagreeing with family and friends. Though many of these obstacles seemed insurmountable, these young authors were able to meet them head-on with persistence and resilience, building the bridges necessary to overcome their personal barriers.

Incorporating time and space for key 21st century skills.

By G. FAITH LITTLE

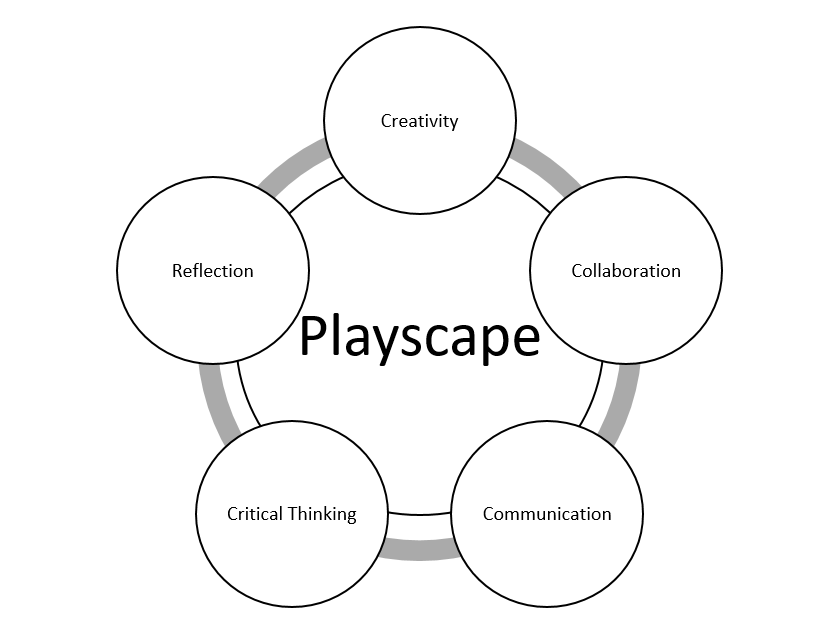

Being aware of 21st century skills as a common phrase and focus in our schools is a first step many of us have taken toward planning and teaching for our students. We are integrating the language. We may have even tried a project as an assessment for one of our units. Yet, making the shift into full integration of real-world projects that set the stage for our students to practice these skills regularly eludes us. Uchenna Ogu and Suzie Reynard Schmidt, in their article The Natural Playscape Project: A Real-World Study With Kindergarteners beautifully articulate a design that can be applied across grade levels and content areas. Students are the authors of their own playscape, with teachers as their guide and support. In this case, playscape refers to the natural playscape created by kindergarteners — a “playground with as few human-made components as possible”. The process brings together research, exploration, and the hard work of thinking and taking action, both individually and collaboratively, where the playscape is not a final project for the purpose of assessing learning. The playscape is the unit.

Playscape

Lesson: The playscape is “designed to bring children back to nature and offer a wide range of open-ended play possibilities that allow children to be creative and use their imaginations.” Application prompt: What is the playscape for your classroom? Consider the landscape students could create and navigate in math, social studies, foreign language, physical education, literature, or science. What world could they build that would engage their senses and invite them to learn in order to create?

Creativity

Lesson: “To begin the project, teachers shared their own knowledge from studies about play and sustainable schoolyards with the children.” Teachers went on to share a text the children read together and articulated some boundaries for their building: "You may build houses small and hidden for the fairies, but please do not use living or artificial materials." “With inspiration and wonder, we set off to imagine, play, and invent small worlds for fairies and other fantastical and real woodland creatures at a nearby park and on an empty back lot on the school campus that eventually became our natural playscape.” Application prompt: What knowledge from your own field of study do students need in order to begin to plan or build their playscape? What texts will open new possibilities for them or serve as foundations for their invention? Consider what knowledge students truly need to begin and what knowledge it makes sense for them to discover on their own. Invite them to discover for themselves, serving as a mentor or guide rather than an expert giving out all the answers.

Collaboration

Lesson: Plan and prepare for meaningful collaboration: “…teachers offered each pair of children a tray of sand. Teachers provided glass beads, twigs, seashells, and other natural materials, as well as time to play, experience, create, imagine, and explore. Children used these materials to create small worlds, miniature playgrounds, or fairy houses. Teachers then asked the children to draw on all of their previous experiences, both indoors and out, to generate a comprehensive list of materials that they might want or need when designing their miniature playscapes. Pebbles, seeds, dirt, grass, leaves, and flowers all made their way onto the list and eventually into their work…Next, teachers invited the children to collaborate in small groups to create miniature playgrounds for the fairies and small woodland creatures.” In the third year, the second-graders, who were the originators of the project while in kindergarten, rejoined the process as collaborators and consultants. Application prompt: What mini-scape could students create as a model for their larger playscape? Instead of listing the materials they may need, support students in generating their own lists of materials. As a mentor, you may do the advanced work of obtaining possible materials, but have them waiting in the wings. Let students take ownership by asking for what they need. When grouping students to collaborate, give each student a specific role that requires an outcome, so that each person’s contribution can be seen.

Communication

Lesson: Committees were formed to investigate a specific aspect of the playscape in depth. After learning more deeply about their subject, children shared what they learned. “For example, since it was important to the current kindergartners to invite birds to the playscape, those involved with the Birdhouse Committee researched native Missouri birds and built birdhouses.” The committee members expressed their love for birds through letter writing, addressing their notes to the birds themselves and including important details from their learning, “We are bird experts. We can tell you apart. You are really cute. We hope you like to splash in the birdbaths. We made them look like flowers, because we thought you might like that.” Application prompt: What are some buckets of information or concepts all of your students will need to understand in order to create a useful playscape? Consider grouping them and naming the groups as it makes most sense in your field. Are they architects? Technical writers? Applied mathematicians? Statisticians? Commentators? In what genres do people in these roles write?

Critical thinking

Lesson: “Being on the committees engaged the children by allowing them to research and pursue one aspect of the playscape with depth.” At one stage in the process, kindergarteners were matched with second graders to explore their design process further. “The two age groups facilitated and scaffolded each other's learning as they talked about, represented, reflected on, and began to evaluate aspects of their own and their partners' design ideas.” Application prompt: Whether it’s pairing students in different grade levels or perhaps pairing students with complementary skills, how can you support students to listen to their partner, communicate clearly, and come to an agreement on next steps? What skills do you need to teach? What practices should students engage in to get the most out of their collaboration in order to sharpen their own critical thinking skills?

Reflection

Lesson: Ongoing reflection is key. During: “Throughout the natural playscape project, teachers encouraged children to frequently reflect on their experiences.” After: “At the end of the study, as a way to help children reflect on their growth and learning, teachers asked them questions about their experiences.” Application prompt: What structure will you support, or put in place, so that students reflect after each step of their process? This reflection will allow them to quickly make use of their learning, going back to foundations or taking a risk, based on their findings. What will the final reflection look like? How can you support student to design their own reflection?

Consider responding to each application prompt as you plan for next year. Whatever grade level you teach, incorporating space and time for creativity, collaboration, communication, critical thinking, and reflection for your students will boost their 21st Century skill set!

Encourage students to adjust their writing style based on their intended audience.

Do you change the style, tone, and format of your writing depending on who the writing is for? Of course you do. Do you teach your students to do the same?

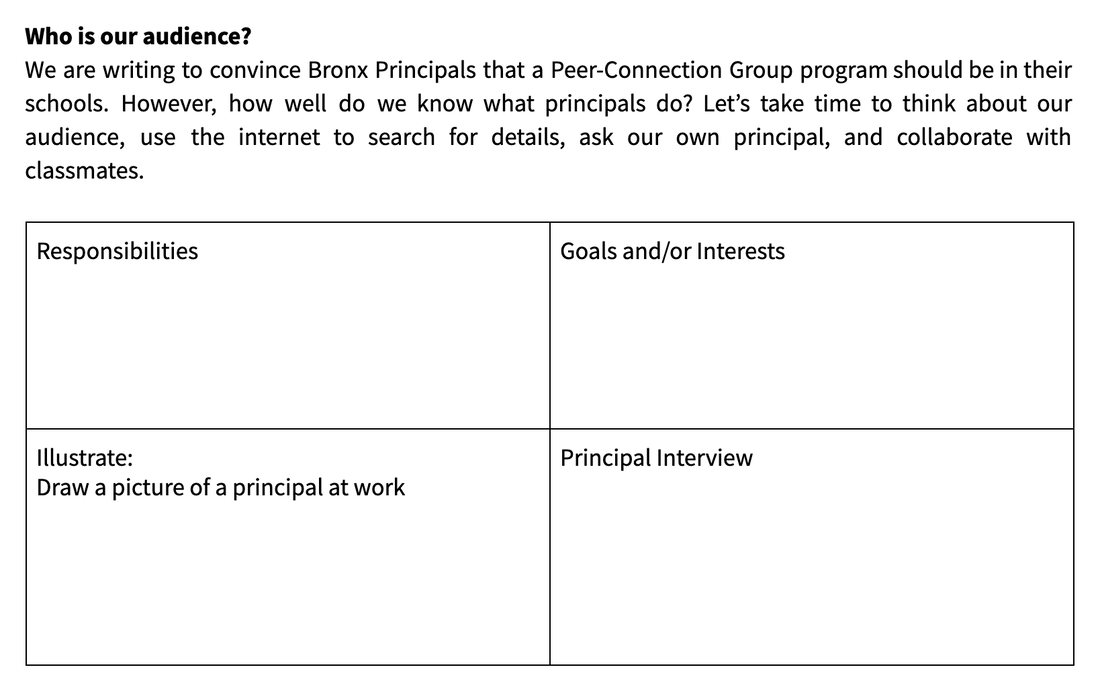

Whatever your answer, it’s important for student writers to truly analyze, discuss, and contemplate their audience. Thinking about the audience they are writing for can inject a different form of energy into students and subsequently, their writing. In addition, getting students to adjust their language and writing style based on the audience they’re interacting with is a transferable, life-long skill that will benefit them down the road. I recently introduced a Student Press Initiative project in an 11-12th grade class at one of our long-time partner schools, the Bronx’s Morris Academy of Collaborative Studies (MACS). This class, which is labeled as a Peer Group Connection (PGC) class, consists of 25 junior and senior students that act as peer mentors for incoming freshmen. These 25 PGC students participate in weekly outreaches with freshmen to help support their transition to the academic and social challenges of high school. Peer mentors and mentees that participate in PGC express an increase in their academic achievements, developed social/relationship skills, and are more motivated to graduate high school. Given the impact of this program, the staff and students at MACS wanted every high school in the Bronx to include a peer-mentorship program in their curriculum, and decided the book we would create would promote the PGC program to other principals in the Bronx. And thus, we had our audience.

Who is our audience?

Throughout this project, the students’ writing has been powerful, raw, and passionate. At times, the energy in their writing was so strong that it was challenging to harness and refocus that energy to address our specific audience. To help students keep their audience in mind when writing, we used a few strategies. First, we (myself and the PGC teaching staff) organized the students into three writing groups: pathos, logos, and ethos. We created these writing groups to design an environment in which students could constantly engage with and think about their audience. In addition, these rhetorical devices helped influence students to produce persuasive writing from day one, which added another layer of excitement into the writing process. Second, I designed a graphic organizer called “Who is our Audience?” for students to reference. This tool allowed students to explore their audience (Bronx principals) in multiple ways — what are their interests, their responsibilities, their goals? This activity proved to be influential for students, as it tested their interview skills, allowed them to receive direct feedback from their intended audience, and become more informed writers.

Lastly, we designed a Feedback Rubric that we could use with students while revising their writing. This rubric provides a checklist that writers can reference at any point throughout the writing process, and requires evaluators to reference specific examples from the text. See below for an example of the rubric and how you might complete each section.

Feel free to adjust our graphic organizer and rubric to your own needs, or use them as a starting point for your own project! If you’re interested in seeing the product of our collaboration with the PGC group at MACS, check back on our new releases page — we’ll be releasing our publication with MACS on May 31st. I wouldn’t be surprised if the writing included in this publication convinces you to introduce a peer-mentorship program at your school!

Project-based learning through stop motion.

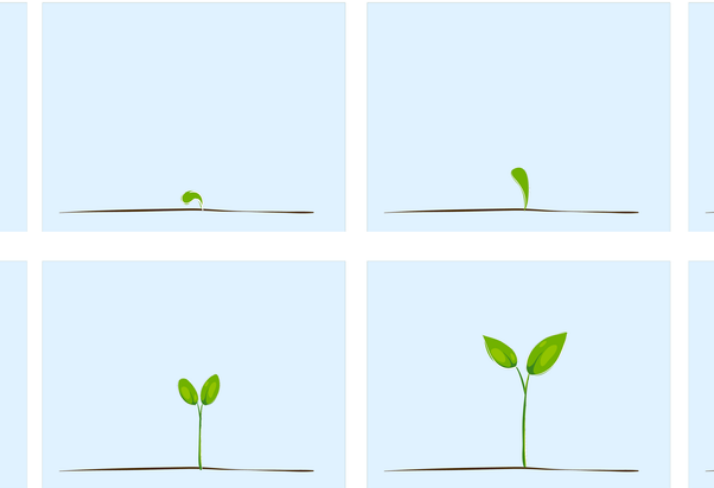

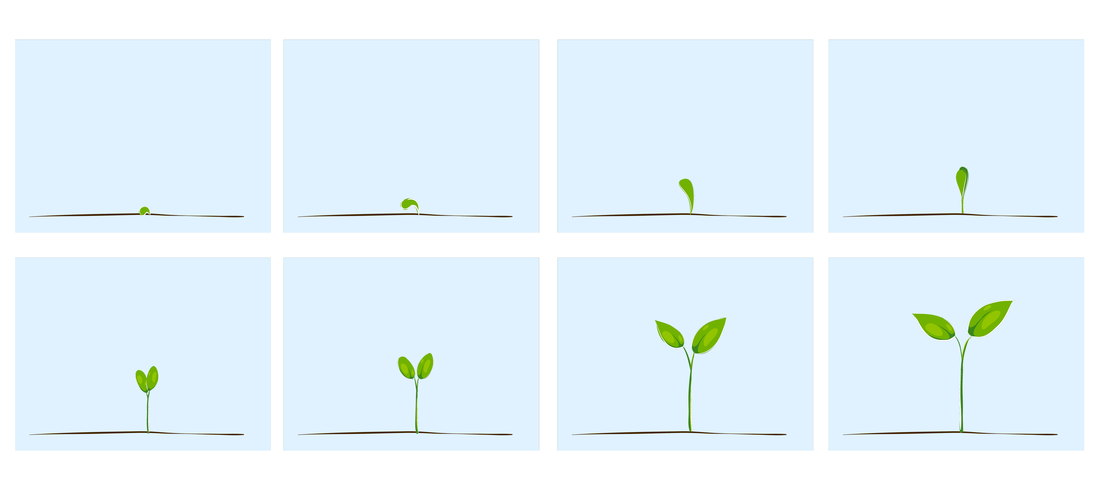

Each year at our Big Learning Challenge institute, we harness the power of 21st century capacities and offer educators the opportunity to navigate the project-based learning process as participants, as well as teachers looking to implement new instructional strategies in their classrooms.

At our last institute, we explored the theme of seeds, and set out to address the question: what happens when you plant a seed? In a unique stop motion workshop, we allowed teachers to determine how to represent their response (literally, or with an abstract interpretation?), decide on a story line (which scenes would they include?), and create their props using clay and paper. It wasn't child’s play, though — they were on a mission to create a stop motion film by the end of our session. Stop motion is a film making technique which uses a sequence of still images to create the illusion of movement. When the individual images are combined, slight movements in the figures that are photographed create “motion” in the film. This technique was fitting for our project-based learning (PBL) focus at the Big Learning Challenge, since PBL is a dynamic approach that allows for collaboration, problem-solving, and creativity.

Using technology to tell stories