|

Three areas of focus for designing rigorous tasks that promote engagement and perseverance.

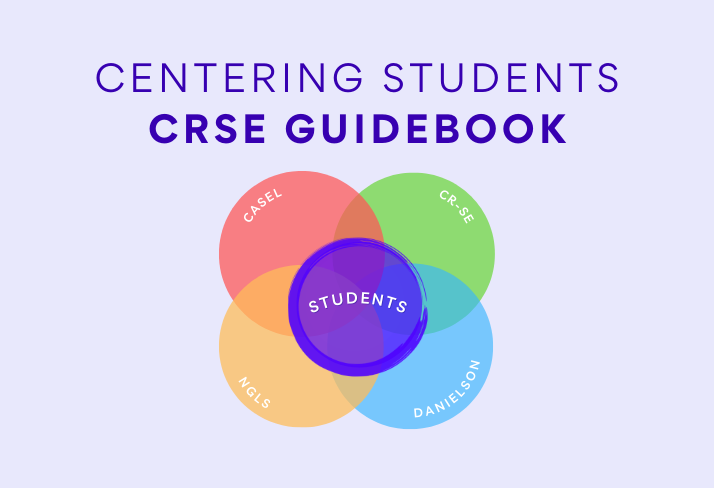

This article is part of our Close Up On CRSE series

“What motivates people to do hard things? Can you think of a time that you persisted in a difficult task, even if repeated efforts to reach your goal weren’t successful?”

This was a question we posed in a recent workshop as we were exploring the challenges of increasing student engagement. Why do people do hard things? In response to this question, we got a wide range of amazing responses. Educators shared examples of everything from finishing their master's thesis, to running a marathon, and even childbirth. The common factor across these and the many other examples provided was that people persist through challenging tasks when they are able to make a clear connection to a personal goal, believe that they have the potential to reach that goal over time, and seek the sense of accomplishment and pride that comes as a result of hard work. The factors that motivate students to persist in challenging tasks are exactly the same! Whether it’s practicing for a sport, exploring a special interest or hobby, or even staying up all night to get through the next level of the video game, we do hard things when the task is motivating, relevant, and gives us a sense of agency or pride.

Articulating the attribute

Centering Students: A Deep Dive into CRSE Practices outlines Rigorous Instruction as one of the five principles of culturally responsive and sustaining pedagogy. It states: “To ensure instruction is truly rigorous, teachers need to be attuned to the specific learning needs of their students and be able to design and implement a wide range of instructional strategies and materials that are responsive to these needs.” One of the key attributes of Rigorous Instruction is Embedding Intellectually Challenging and Diverse Content into curriculum, unit, and lesson plans. This means that teachers implement challenging tasks and use relevant resources that are responsive to the unique learning needs of their students. It also means that they're designing tasks and activities that are diverse, and reflect the real issues of the world in which we live today. This is important because learning occurs when students are intellectually engaged in culturally diverse and relevant content. In book Drive, Daniel Pink brings together decades of psychological research on motivation theory and helps us understand the mindset that cultivates intrinsic motivation, which leads to perseverance and pride. He outlines the three criteria of purpose, autonomy, and mastery as the keys to unlocking personal drive in adults. For students, this might look like relevant purpose, mastery moments, and structured autonomy. This sounds nice on paper, but what does it mean in the real world? How do we create these conditions intentionally for our students?

In the classroom, the first step to embedding intellectually challenging and diverse content is to design an intellectually challenging task connected to our students’ identities, interests, and instructional goals. This means making connections between our content area and critical thinking tasks that include the demonstration of higher order thinking skills, as found on frameworks like Bloom's Taxonomy, Webb’s Depth of Knowledge, or The Cognitive Rigor Matrix, which is a combination of the two. Setting an intellectually challenging task that taps into students’ ability to analyze, synthesize, or evaluate content information takes time and practice. Choosing an entry point and topic from diverse source material is a key to making the task personally relevant.

After setting the task, then we can begin creating the conditions that cultivate motivation and perseverance.

Relevant purpose

If we look back at the conditions that create perseverance through challenging tasks, we’re reminded that the common factor is people seeing the task as personally relevant to a specific goal or skill they want to achieve. So often in school, the goals we set for students are outside of their own interests. The state sets the goals on high-stakes exams, our district might set the goals for curriculum or course outcomes, and teachers set in-class goals for what students should accomplish, and why. There are almost no formal structures for students to engage in the process of determining what they want to learn, and for what purpose. While there are real constraints that we’re working with when it comes to content standards, there are many opportunities to tap into students’ interests, and to create relevant purpose for the tasks we ask students to engage in.

Mastery moments

Creating mastery moments means that as we look at our arc of instruction throughout a lesson, a week of lessons, or a unit plan, we identify key moments of the learning process and identify those as micro-targets or mini-goals along the route. Creating some built-in celebrations or rewards for hitting these targets inspires a growing confidence and positive pride that comes from meeting a goal.

Structured autonomy

Autonomy is the ability for a person to choose their own process. Students may not have developed all of the skills needed to stay productive with unstructured autonomy, but structured autonomy is empowering and cultivates skills to help students learn how they work best. Structured autonomy means creating pathways that maximize student choice, preference, and independent work with increasing time on task.

When it comes to student engagement, in an effort to create student-friendly tasks, we often associate more engaging with easier. We don’t want our students to struggle or get frustrated during the learning cycle. But easier isn’t necessarily engaging — and it rarely builds the critical thinking and content knowledge that students need to motivate them to take on the next learning challenge.

Embedding intellectually challenging and diverse content into curriculum is critical to engaging students in a productive learning experience that is equally intellectually challenging and engaging. We can all do hard things when we see the purpose, own the goal, and believe that our success is possible.

Three essential questions to explore as you navigate connecting a curriculum to your classroom.

As the start of the 2023-24 school year approaches, many K-8 educators will find themselves faced with the challenge of adopting a new curriculum. This task can feel overwhelming, leaving teachers and school leaders uncertain about where to begin. To help navigate this process, we can examine three powerful questions that can serve as entry points for understanding and evaluating a new curriculum, helping educators to gain valuable insights needed for making informed decisions that align with their goals and values.

Does it align with school mission & vision?

When introducing a new curriculum, it is essential to ensure alignment with the school’s mission and vision. Consider how a new curriculum reflects the core values, educational philosophies, and goals set by the school. Evaluate whether it supports the desired educational outcomes and adequately prepares students to meet the school’s vision for the future. A curriculum that aligns with the school-wide mission and vision contributes to a cohesive and purposeful educational experience for all students. Evaluating alignment can provide valuable information to inform a school’s decision-making process regarding the adoption of a curriculum and the necessary adaptations and revisions.

Does it support differentiated instruction and diverse learner needs?

Recognizing the diversity of students in a K-12 setting is crucial. It behooves schools to inquire about if and how the curriculum addresses differentiated instruction and caters to students with varying abilities, learning styles, and interests. I would advise schools to look for evidence of accommodations for students with disabilities, support for English Language Learners, and opportunities for personalized learning. Evaluate whether the curriculum provides a range of resources, materials, and strategies that meet the needs of all students. A curriculum that embraces and supports diverse learners promotes equitable access to education and enhances students’ engagement and success. In my experience, differentiation is often a shortcoming of most curricula, so these suggestions can be particularly helpful when it comes to identifying the additional supports and materials that will need to supplement the curriculum.

What assessment methods are incorporated into the curriculum?

Assessment is a vital aspect of any curriculum. When it comes to evaluating and potentially adjusting a new curriculum, inquire about the assessment methods and tools used within the curriculum to measure student progress, understanding, and mastery of concepts. Determine whether the curriculum includes formative assessment to provide ongoing feedback and inform instruction, as well as summative assessments to evaluate student achievement at the end of a unit. Additionally, consider if the curriculum incorporates various assessment formats, such as performance tasks, projects, portfolios, and traditional tests that provide a comprehensive view of students' learning. Understanding the assessment methods and measures helps educators gauge student progress, identify areas for improvement, and tailor instruction. Based on this investigation, you can make the necessary modifications or additions to the curriculum.

As educators embark on a journey of adopting a new curriculum, these questions can serve as valuable guideposts for evaluation. By considering alignment to the school’s mission and vision, supporting differentiated instruction, and assessing evaluation methods, educators can ensure that the chosen curriculum reflects their values, addresses the diverse needs of their students, and provides effective means to measure student learning. Embracing these questions will empower educators to make informed decisions that foster a purposeful and inclusive educational experience for all learners!

Connect the dots between larger goals and the specific needs of your students.

As an instructional coach and elementary specialist for CPET, much of my work with elementary schools has involved helping teachers unpack and make sense of the chosen, school-wide pre-packaged curricula they’re asked to work with — a curricula that is designed by professionals to meet grade level and subject requirements, and includes most, if not all of the materials needed to teach. I often facilitate workshops and professional development sessions, introduce teachers to the curricula and its components, as well as engage in classroom visits and critical reflection conversations with individual teachers to support the implementation of the curricula.

While the curricula is packaged, there’s often a surprising amount of tweaking and adapting involved to make sure the curricula fits the school calendar, the style of the teacher, and most importantly, that it meets the needs and interests of all students. This can be a daunting and challenging task for educators. How can you make sense of and revise curricula to meet the needs, goals, and interests of your students?

Identifying your goals

One of the biggest challenges I see when it comes to the adoption and adaptation of packaged curricula is just the magnitude and density of it all. There are often many components, books, inserts, handouts, and templates, and this can make it difficult for teachers to even know where to begin. They often express feelings of overwhelm or lack of time or opportunity to make sense of and collaboratively plan with the curricula. Because packaged curricula often includes all of the individual lessons, with varying levels of detail and information, teachers often fall into the trap of teaching lesson to lesson and relying on the teacher manuals to drive their day-to-day instruction. But this can result in losing sight of the larger goals and what these lessons are in service of. Essentially, teachers can start to become the mouthpiece of a script. I recently began to work with a school that had just adopted a new curricula for reading. After using a program for a number of years, many teachers were unsure and rather uneasy about this transition. After meeting with leadership and discussing their needs, my goals as the instructional coach were to:

In support of these goals, it was my intention to facilitate a number of workshops with the teachers to first and foremost ease their anxieties, answer questions, and cater to their varying levels of familiarity and comfort with the curricula. From there, we worked together to unpack the curricula in a meaningful and productive way, the specifics of which I will share with you, as I believe they can be helpful when it comes to adopting and adapting any new curricula.

Starting with the end in mind

In order to know where you’re going and how you are going to get there, you need to understand the larger goals and objectives of a curriculum, the driving questions, and the final tasks or assessments. To do this, I would suggest starting with the end in mind. Most curricula I’ve seen offer a unit overview or summaries that are often found at the front. Taking the time to read or skim these overviews can be a helpful starting place. With the teachers I worked with, each grade level engaged in jigsaw readings, where one teacher took on a portion of text from the overviews and underlined and annotated, made comments in the margins, and then shared their thinking, questions and interpretations. From there, we examined the culminating assessment, asking questions such as:

This exercise was intended to not only understand the assessment as it’s suggested, but more importantly, to provide a lens through which to recognize opportunities for revision, including scaffolding or extending the task, and then consider the implications for instruction. No curricula can take into account the needs and interests of all students, so it is up to teachers to revise and adapt the curricula with their students in mind. Lastly, we considered the necessary materials, resources, rituals, and routines that would be needed in order to implement the units successfully:

With this larger, more robust understanding of the curricula, teachers can more effectively navigate their curricula and instruction and move away from feeling bound to a script.

Pushing into the pacing calendar

Most often, pre-packaged curriculum includes a pacing calendar, sometimes called a scope and sequence. This calendar offers a snapshot for instruction, including when particular units, (also known as modules or bends) should be implemented, and for how long. These calendars can be helpful when thinking about a school year at large — where you’re going, and how long it’s going to take you to get there. In my experience, the suggested pacing calendars often need to be changed or revised to take into account breaks, testing, and school events. Perhaps more importantly, the pacing calendars need to be adjusted based on teachers’ understanding of the larger goals, objectives, and assessments. With my teachers, we compared the suggested pacing calendar to their school calendar and grade-specific calendars, asking questions such as:

Asking these questions supported teachers in taking action to make adjustments. Having a larger calendar for instruction can make things feel more manageable.

Identifying the structure of instruction

In my experience, most packaged curricula have a consistent structure and organization, and even specific rituals and routines that define the units and individual lessons. Looking across the lessons and identifying these structures can be very helpful for teachers. Examples include rituals and routines like turn and talks, reflective writing, stop and jots, or structures such as progressive scaffolding. The adopted curricula of this particular school was organized around the workshop model, starting with a connection which led to a mini-lesson, an opportunity for student practice, and then culminated with a share out and reflection of the learning. I supported teachers in understanding and unpacking these various components and their purpose and then modeled a few of the lessons for them. To facilitate this, we used a template to plan one or two of the lessons, adopting what we liked, and taking out what we felt wasn’t necessary. We revised anything necessary, based on our larger understanding of the goals of the lesson and what teachers thought would be most relevant and important to students. Lastly, we worked to revise the lesson to ensure it reflected their voice and their style, fostering a sense of authenticity and ingenuity that supports relationship-building with students. By identifying and understanding the key structures, rituals, and routines of a curriculum, teachers can move through the lessons with more clarity and confidence.

Implementing packaged curricula takes a great deal of patience, persistence, and flexibility. We know that no curriculum can be implemented as it’s written if it is going to meet the needs and goals of a particular school community. We have to work strategically, creatively, and collaboratively with our peers to examine the curricula, consider aspects we can and should implement, and what needs to be revised, replaced, or even eliminated.

Are you adapting curricula in your classroom or community? Get in touch with me to receive support throughout the daunting — but doable! — process.

Make sense of your thinking as you articulate the what, why, and how of your lessons.

My most common resistance and response, when prompted by our director to articulate my next workshop plan in one of our templates is, “We don’t have time for that. I need to get in there and get the work done. I don't have time to also articulate what the work is going to be.” After I express my frustration with a lack of time, I take a breath and sit down with my thoughts, our goals, and the template.

Thankfully, the template has been through our usual practice of draft, revision, practice, and more revision, so that I’m working with a helpful, useful, and practical tool. As I move through prompts like driving questions, objectives, skills, activity, assessment, and resources, I see what’s in my head come together on the screen. By the time I’m done, I’ve experienced the magic of a pre-planning template. I’ve actually done all the work of thinking through what I’m doing, why I’m doing it, what skills I need to teach, and how I will confirm what students know and can do throughout the workshop. Not enough time to plan? I actually don’t have enough time NOT to plan! As it turns out, articulating my plan supports me in grounding the lesson in its larger context and provides a way to make my thinking visible to my students, my colleagues, and my supervisor. Bonus: I won’t need to reinvent an agenda the next time this workshop rolls around. I have a lesson plan I can reuse and customize going forward.

Our lesson planning resource supports teachers like you in experiencing this same process — moving your thinking from inside your head out into the world, and considering all of the pieces of a lesson, because the template reminds you with supportive prompts. You can leave yourself room to think more deeply about teaching and learning by relying on our preset categories to pull you through your planning time.

It’s important to be confident and clear about your plans, and articulating your thinking is an excellent way to get there. This is what will allow you to be more flexible, because you’ve got a plan from which to work. You know what’s essential and what might be able to shift when unexpected changes occur in your classroom, as they so often do! You can use this resource as a tool for yourself as we teach, your students as they engage in the work, and your colleagues as you offer each other formal or informal coaching in this challenging and rewarding world of teaching.

Incorporate PBL into existing tasks and create engaging, meaningful opportunities for your students.

Project-based learning is a widely used term in education. Although many educators have a general understanding of what it means, it’s often met with uncertainty and apprehension.

A simple Google Search of “project-based learning” results in 10 pages of articles or blogs, written by various organizations, institutions, and individuals. For instance, cultofpedagogy describes project-based learning as a combination of standards, best practices of UBD (understanding by design), and formative assessments. ASCD describes a project as meaningful if it fulfills two criteria: that students "feel the work is personally meaningful, as a task that matters" and that the project fulfills a “meaningful purpose.” Edutopia describes project-based learning as learning that tells a story. Throughout my 15 years of teaching and coaching, I’ve seen varying interpretations and implementations of project-based learning myself, which have been further complicated by the move to remote and blended learning environments. For educators who are working with packaged curricula, it can be especially difficult to see the opportunities available for introducing PBL in classrooms. But focusing on the core components of this work can support us in establishing engaging, meaningful, and doable project-based learning experiences for our students.

Components of project-based learning

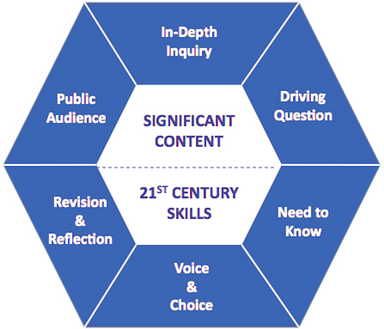

One of the most well-known and admired institutions when it comes to project-based learning is the Buck Institute. They offer what I think are very helpful criteria to inform what project-based learning can look like:

In line with much of the graphic, our K-12 coaching team believes that projects are a wonderful way to help students cultivate 21st century skills, focus on a pressing topic or issue, develop their identity as readers and writers, and engage in a writing process that involves extensive feedback, revision, and reflection on their learning. We believe the pedagogy of project-based learning is about:

Now that we’ve laid out some of the basics, we can investigate what project-based learning might look like in action. The questions above can help inspire task revision and allow you to incorporate project-based learning into pre-packaged curricula, without starting from scratch.

Creating relevant, meaningful tasks

Recently, I partnered with a school in Brooklyn to support them as they designed and reimagined assessments for online learning. As an elementary school, they had adopted a packaged curricula for English Language Arts instruction. My goal was to help them make existing tasks and assessments more engaging and relevant for students, and support them in redesigning the tasks as they were written in order to infuse elements of project-based learning — without compromising rigor. We began with a first grade writing task that focused on persuasive reviews based on favorite places, foods, etc. To begin revising this task, we started by examining three important questions, informed and inspired by the Buck Institute:

We used these questions to guide our analysis and revision, referring back to the original task:

Turning the task into a project

Now that we have been able to identify the basic possibilities and challenges with this task, we can continue on to revision, and begin to shift our original task into a project. When it comes to developing authentic and meaningful projects, we like to turn to a promising practice called GRASPS. This stands for: G: What is the goal of the project? R : What is the role of the student? A: Who is the audience? S: What is the structure of the writing? P: What is the purpose? In conjunction with our earlier questions, the GRASPS framework is a helpful tool in redesigning tasks and ensures that our revisions are clear. In our example, the responses look something like this:

Equipped with these revisions, we can now more easily shift the original writing task to one that is project-based, and understand how we can introduce these ideas to students. This not only generates excitement for students, but teachers as well — our partners in Brooklyn were eager to plan and implement this project within their classrooms, and were excited about the additional possibilities for creativity.

What I hope is evident throughout this process is that project-based learning can have a variety of entry points — whether you’re teaching remotely or in-person, creating your own projects, or reimagining pre-packaged curricula. Regardless of your situation, recognizing how instruction can be meaningful, relevant, and doable — even with the current parameters of teaching and learning — is possible.

A three-step process for unpacking and implementing a pre-packaged curriculum.

A well-developed and effective curriculum is the cornerstone of an excellent education. Many schools go to great lengths to ensure that they can identify a highly-rated curriculum on behalf of their students. This often means spending a great deal of money to purchase a complete, professionally-designed curriculum which may include textbooks, web-based resources, unit plans, scripted lesson plans, and student-facing resources.

But there’s a big difference between having the curriculum and teaching the curriculum. It isn’t as simple as reading aloud from the Teacher’s Guide. Unpacking a pre-packaged curriculum takes focused and continuous effort on the part of teachers and their whole school community. When we work with schools who are implementing a new curriculum, we advise using a three-step process: adopt, adapt, apply.

Adopt

The curriculum is the driving force behind the teaching and learning within a course. Whether a school is moving from one curriculum to another, or moving from teacher-designed to a pre-packaged curriculum, there’s a lot of work that goes into adopting something new. We encourage school leaders and teachers to unpack the curriculum materials by focusing on three main pieces — structure, key components, and tensions — and making connections to current instructional practices, student culture, and school climate.

Adapt

Even the very, very best curriculum cannot be used straight out of the box. For a curriculum to be highly effective, it must be adapted to meet the needs of students, the style and personality of the teacher, and the mission and vision of the school community. After taking time to understand the curriculum’s structure, key components, and tensions, we’re ready to begin making adaptations.

Apply

After adopting the curriculum by unpacking its components, and adapting the curriculum to meet the needs of the community, educators will feel more confident to begin implementing the curriculum.

Curriculum design is an intensive and demanding process. Schools and districts can save teachers time by investing in high-quality curricula that allows teachers to focus on implementing instruction rather than on curriculum design. But in the process, we must remember that it isn’t as simple as pulling it out of the box and reading aloud from the book on the day of the lesson. School leaders will want to create space and time for teachers to analyze the adopted curriculum, make adaptations necessary to meet students’ needs, and apply it in their classes after critical reflection and opportunities for revision. Following through with these practices will ensure that the curriculum is being implemented with fidelity, integrity, and authenticity.

Make the most of your time and energy by using a batching strategy for your planning.

By the time you’ve cultivated a course curriculum, it’s easy to run out of steam as you move into building a unit plan, the detailed guide that will support your lesson planning. One way to make the most of your time and energy is to plan using a batching strategy. We can think of this like grocery shopping for the week.

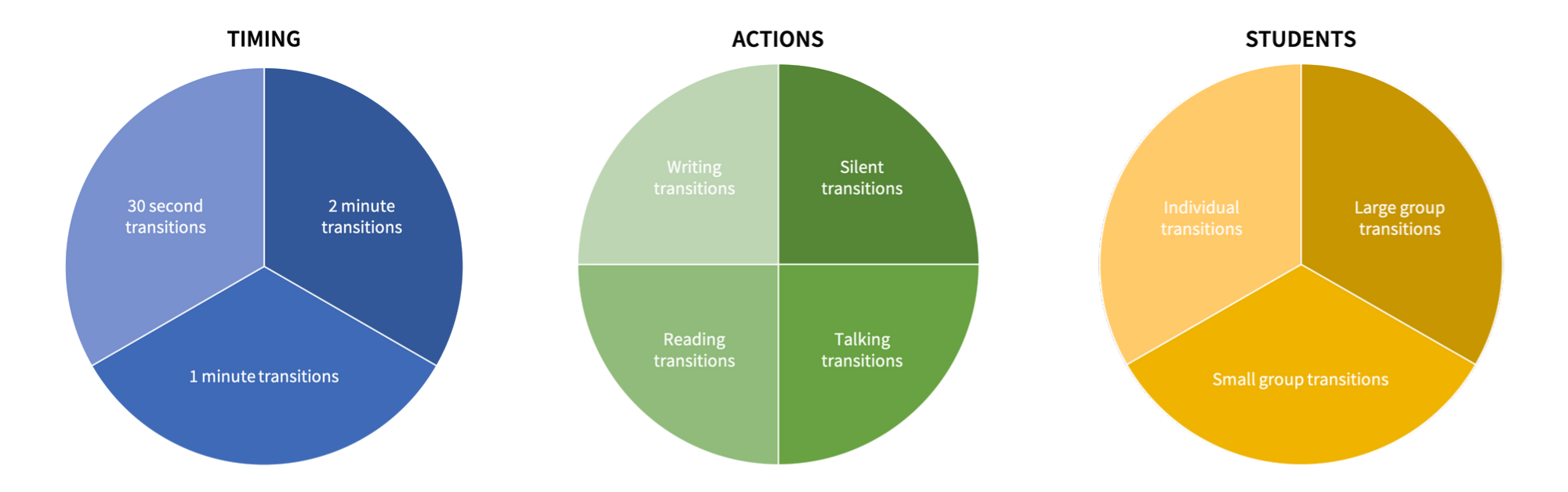

If I walk down the aisles (online or in real life), filling my basket with ingredients for Monday (breakfast, lunch, dinner) then Tuesday (breakfast, lunch, dinner) and so on, the trip will take a while. If I shop by meal type, like breakfasts, lunches, and dinners, I cut down on the time and effort I spend. Of course, it’s even faster when I identify ingredients that can be used for more than one meal type. I pick up eggs to scramble for my breakfast sandwich and hard boil for my evening salads. I grab apples to go in my lunch box and morning smoothie. Like grocery shopping, when we identify areas in our unit plan that we can create or gather in batches, we cut down on the time we need to design that part of our plan. For instance, if we want to include transition tools for teachers to use in their lesson planning, we could develop our list in a batch starting with our own ideas and incorporating others:

Batch your transitions depending on what you and your students need in the classroom — is it about needing time? Do you want students to read, write, or talk to one another, or should they quietly move from one activity to the next? Do your transitions depend on whether students are individually working or in groups? Batch them in a way that works best for you, and drop the transitions you’ve collected into the batch that makes most sense:

One you have your lists together, it’s simple to drop transition tools, one at a time, into logical places in each unit plan. Even quicker, and possibly more empowering for other teachers, is to turn the list into a menu of options teachers can use to find what works best for their teaching style, content area, and students.

Here’s a menu we developed for educators at Jewish Home Lifecare who were teaching students how to provide services that support health, individuality, and dignity to elders. This menu allowed novice teachers to review a number of options and find transitions that were a match for their teaching style and their students for that session. Even the simplest of menus can be a good jumping off point for generating new ideas!

Whiteboard agenda

Writing out a simple agenda is helpful for easing transitions — it makes it clear where we are and what's to come. Write agenda on the whiteboard (sample below):

Check items off the list as you complete each activity/task so students know where they are in the plan for the day. Invite a student to read off what’s next as you go through the day and/or to reiterate what they’ve already accomplished. Bonus tip: Have a very chatty/active student? Make them Agenda Leader for the day. They should help you stay on schedule by recounting what has been done and reading what should happen next.

Time to learn!

Play this as a little game that will result in a call & response. The more you practice this, the more the students will come to experience it as a cue to look up and engage. It takes a bit of time, so be bold and power through until this becomes a ritual.

This also works to get them back on their current task if they get distracted. Play around with ways to use this method, modifying it to fit what works for you and your students.

Organizing student groups

One of the hardest transitions to make is moving from individual work to group work. An effective way to guide grouping is to use post-it notes with a number or a letter, colored paper, or even playing cards. Using one of these items helps students organize themselves in their groups all at once, rather than calling out every student's name individually or having students wander around the room "looking" for a group.

Two-minute timer

Two minutes before one activity ends and another begins, make announcements about how much time is left and what students will be doing next (including what they need to have to move forward). Examples:

Deep breath

You're ready to move on to the next instruction!

The pressure to plan your curriculum it in just the right way can be overwhelming. How can you make sense of the process?

By ROBERTA LENGER KANG

When the back to school sales are at their peak, students and parents are picking out the cutest notebooks and the coolest backpacks. Meanwhile, educators are feeling the pressure and anxiety that comes with the start of the school year — particularly as they think about their curriculum. Different school communities and districts have different approaches to designing curriculum. Some purchase big box curriculum sets with prescribed lessons, while others have the opportunity to design their own, which can be exciting — and also a bit daunting. Cultivating a course curriculum is one of the most important and most complicated tasks for educators. It requires deep content knowledge and an accurate anticipation of student ability throughout the school year. Teachers need to differentiate the most important content and the most important skills in the most effective sequence — all while knowing that the decision to teach one thing is also the decision not to teach a hundred other things. The pressure to plan it in just the right way can be overwhelming. This process will always be a challenge, but it doesn’t have to be painful! In our curriculum-focused coaching projects, we support educators as they examine, design, implement, and refine customized or adapted curricula. Each educator and classroom is unique, but curriculum planning often brings up common questions. Below are some of the most frequently asked questions we hear from educators as we support them in the planning process.

What goes into a curriculum map?

A well-developed curriculum map should provide an overview of the course at-a-glance. Maps are most valuable when they include a clear picture of the course goals, how those goals intersect with the content knowledge, thinking skills, relevant standards, and a plan for assessments. Here’s a good checklist for a curriculum map:

What’s the difference between a curriculum map and a unit plan?

A curriculum map provides an overview or summary of the course, while a unit plan provides the details needed to develop each individual lesson. A unit plan may include specific resources to use in a particular unit, a pacing calendar that outlines the learning goals for each week or each day, lists of vocabulary words, and a plan for differentiating instruction for different learners. Unit plans tend to be longer and include more explicit plans that illustrate the arc of the unit and provide the necessary details to develop daily lesson plans. There is a critical distinction between the curriculum map as an overview and the unit plan as the detailed guide to support lesson planning. Curriculum maps that include unit plan-level details often become massive documents that are difficult to read. They can become a dumping ground for edu-speak-jargon that doesn’t really mean anything. As educators, we want to remember that these documents are tools to support and facilitate our planning process. If they don’t do that, they aren’t ultimately very valuable.

How much detail should be included?

When it comes to the curriculum map, we want to include information clearly and succinctly, which means we can eliminate jargon or unnecessary details. For example, it’s valuable to list relevant standards on a curriculum map because it will give a picture of how all standards are being addressed throughout the school year and how they’re sequenced within each unit. However, standards often have a lot of very specific, formal language. Simply copying and pasting the entire standard into the curriculum map is thorough, but not always helpful. It isn’t reasonable to expect that anyone will read with that level of specificity, it isn’t particularly helpful to teachers who need to see these standards broken down in the unit plan, and it can become extremely repetitive if the units utilize the same standards. In these situations, we recommend using the standard code, and summarizing the standard in a short phrase or sentence. This provides a simple and clear alignment with the standard, demonstrates the educator’s understanding of the standard, and keeps the information focused and clear. The same rule can be applied in other categories as well.

How should the map be formatted?

Formatting is often a personal choice, and different people prefer different styles. We recommend using a horizontal chart with a column for each critical component, and a row for each unique unit. The value of this format is the at-a-glance nature. If we can read from left to right along a row, we’re getting an overview of each unit in the course. When we can complete the curriculum map in 1-2 pages, we get a good picture of the course goals and the sequence of learning the students will experience. This allows the curriculum map to act as a touchstone planning tool for teachers, and becomes a great document to share with school leaders, parents, and even students.

Can curriculum maps be changed?

One of the things that makes writing curriculum a daunting task is the sense of its permanence. It makes sense to want to keep the curriculum fluid, as the most effective teaching is influenced by a wide range of variables like current events, student cohorts, and shifts or changes in the field. The fear of permanence can often become a justification for not creating a curriculum map. But the benefits of long-term planning, for teachers especially, cannot be underestimated. The most effective curriculum maps are living documents that provide planning support to teachers throughout the year and communicate the intentions of the course to others (administrators, parents, students, other teachers). We recommend that teachers regularly reflect on their lessons and unit plans as they’re implementing the curriculum so that they can make adjustments, remember what worked and what didn’t, and update the curriculum as necessary. We revisit our curriculum over the summer or at the beginning of the school year to account for the learning of the previous year.

What are the steps I should follow to make a curriculum map?

In the curriculum mapping process, we see a relatively consistent approach that favors backwards planning, which suggests that teachers should first determine the end point (the ultimate goal or final assessment) and then plan backwards from there. This process is meant to create a clear alignment between content, skills, and instruction. If this process works for you, use it! The problem is that this process doesn’t apply to all teachers or all situations. When it doesn’t work, it can create major obstacles in the development process. Our recommendation is to start with what you know, generate your ideas based on any entry point you can find, and fill in the blanks along the way. Then, reflect and revise on the plan from an alignment perspective to ensure that the planning process maintains instructional integrity. |

|

The Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) at Teachers College, Columbia University is committed to making excellent and equitable education accessible worldwide. CPET unites theory and practice to promote transformational change. We design innovative projects, cultivate sustainable partnerships, and conduct research through direct and online services to youth and educators. Grounded in adult learning theories, our six core principles structure our customized approach and expand the capacities of educators around the world.

|

ABOUT US

525 West 120th Street, Box 182 New York, NY 10027 416 Zankel Ph: (212) 678-3161 cpet@tc.edu Our Team Career Opportunities |

RESOURCES

Professional Articles Ready-to-Use Resources Teaching Today Podcast Upcoming PD Opportunities |

COACHING SERVICES

Custom Coaching Global Learning Alliance Literacy Unbound New Teacher Network Student Press Initiative |