|

Three areas of focus for designing rigorous tasks that promote engagement and perseverance.

This article is part of our Close Up On CRSE series

“What motivates people to do hard things? Can you think of a time that you persisted in a difficult task, even if repeated efforts to reach your goal weren’t successful?”

This was a question we posed in a recent workshop as we were exploring the challenges of increasing student engagement. Why do people do hard things? In response to this question, we got a wide range of amazing responses. Educators shared examples of everything from finishing their master's thesis, to running a marathon, and even childbirth. The common factor across these and the many other examples provided was that people persist through challenging tasks when they are able to make a clear connection to a personal goal, believe that they have the potential to reach that goal over time, and seek the sense of accomplishment and pride that comes as a result of hard work. The factors that motivate students to persist in challenging tasks are exactly the same! Whether it’s practicing for a sport, exploring a special interest or hobby, or even staying up all night to get through the next level of the video game, we do hard things when the task is motivating, relevant, and gives us a sense of agency or pride.

Articulating the attribute

Centering Students: A Deep Dive into CRSE Practices outlines Rigorous Instruction as one of the five principles of culturally responsive and sustaining pedagogy. It states: “To ensure instruction is truly rigorous, teachers need to be attuned to the specific learning needs of their students and be able to design and implement a wide range of instructional strategies and materials that are responsive to these needs.” One of the key attributes of Rigorous Instruction is Embedding Intellectually Challenging and Diverse Content into curriculum, unit, and lesson plans. This means that teachers implement challenging tasks and use relevant resources that are responsive to the unique learning needs of their students. It also means that they're designing tasks and activities that are diverse, and reflect the real issues of the world in which we live today. This is important because learning occurs when students are intellectually engaged in culturally diverse and relevant content. In book Drive, Daniel Pink brings together decades of psychological research on motivation theory and helps us understand the mindset that cultivates intrinsic motivation, which leads to perseverance and pride. He outlines the three criteria of purpose, autonomy, and mastery as the keys to unlocking personal drive in adults. For students, this might look like relevant purpose, mastery moments, and structured autonomy. This sounds nice on paper, but what does it mean in the real world? How do we create these conditions intentionally for our students?

In the classroom, the first step to embedding intellectually challenging and diverse content is to design an intellectually challenging task connected to our students’ identities, interests, and instructional goals. This means making connections between our content area and critical thinking tasks that include the demonstration of higher order thinking skills, as found on frameworks like Bloom's Taxonomy, Webb’s Depth of Knowledge, or The Cognitive Rigor Matrix, which is a combination of the two. Setting an intellectually challenging task that taps into students’ ability to analyze, synthesize, or evaluate content information takes time and practice. Choosing an entry point and topic from diverse source material is a key to making the task personally relevant.

After setting the task, then we can begin creating the conditions that cultivate motivation and perseverance.

Relevant purpose

If we look back at the conditions that create perseverance through challenging tasks, we’re reminded that the common factor is people seeing the task as personally relevant to a specific goal or skill they want to achieve. So often in school, the goals we set for students are outside of their own interests. The state sets the goals on high-stakes exams, our district might set the goals for curriculum or course outcomes, and teachers set in-class goals for what students should accomplish, and why. There are almost no formal structures for students to engage in the process of determining what they want to learn, and for what purpose. While there are real constraints that we’re working with when it comes to content standards, there are many opportunities to tap into students’ interests, and to create relevant purpose for the tasks we ask students to engage in.

Mastery moments

Creating mastery moments means that as we look at our arc of instruction throughout a lesson, a week of lessons, or a unit plan, we identify key moments of the learning process and identify those as micro-targets or mini-goals along the route. Creating some built-in celebrations or rewards for hitting these targets inspires a growing confidence and positive pride that comes from meeting a goal.

Structured autonomy

Autonomy is the ability for a person to choose their own process. Students may not have developed all of the skills needed to stay productive with unstructured autonomy, but structured autonomy is empowering and cultivates skills to help students learn how they work best. Structured autonomy means creating pathways that maximize student choice, preference, and independent work with increasing time on task.

When it comes to student engagement, in an effort to create student-friendly tasks, we often associate more engaging with easier. We don’t want our students to struggle or get frustrated during the learning cycle. But easier isn’t necessarily engaging — and it rarely builds the critical thinking and content knowledge that students need to motivate them to take on the next learning challenge.

Embedding intellectually challenging and diverse content into curriculum is critical to engaging students in a productive learning experience that is equally intellectually challenging and engaging. We can all do hard things when we see the purpose, own the goal, and believe that our success is possible.

How to recognize patterns in student performance as you take your next steps toward strategic instruction.

Analyzing data from high-stakes exams is:

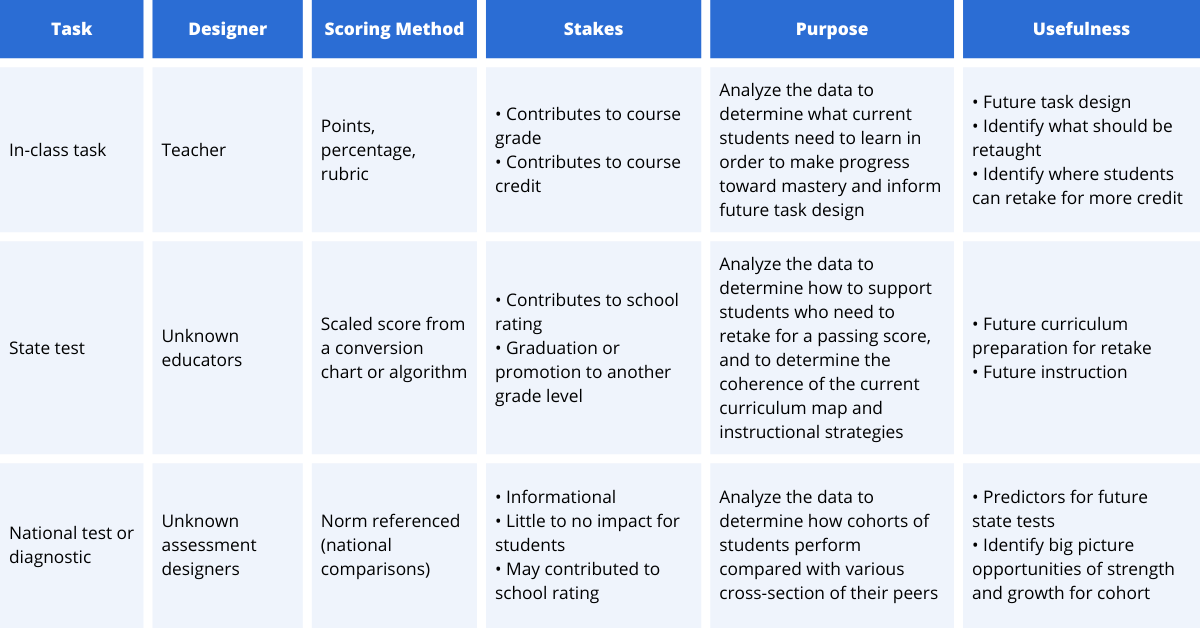

Answer: D — All of the above While promising practices for using data to inform instruction are well intentioned, the process and impact often misses the mark. It can become an overwhelming and confusing experience that can pull educators into sinkholes that produce unreliable conclusions and eat up valuable time and resources. How can we yield the benefits of data analysis and avoid these drawbacks? Analyzing data is valuable because it helps us zoom out from individual results to recognize the patterns and trends in performance, so that we can make choices in the future that will benefit our students. But depending on the type of data we’re analyzing, and the purpose, how we approach the analysis and the conclusions we draw can change dramatically.

Where did the data come from?

Let’s start with the basics. When analyzing data, we want to be clear about where the data came from, and how it was produced. We can draw different conclusions and take different action steps if we’re analyzing a task we designed, or analyzing results from a national diagnostic. For example, when analyzing an in-class assessment, if the teacher realizes that most of their students missed question #3, they can look at question #3 and realize that it’s confusing and rewrite it for a future exam, or eliminate it from the students’ grades. However, if they’re analyzing question #3 from a state test, they have no control over the question or its wording and they can’t eliminate it from their students' grade. Knowing where the data comes from, who designed the task, how the task was scored, and the stakes connected to the data will help us determine our purpose for the analysis and the usefulness of the data.

When was the data collected?

Another key factor we want to be aware of is the time between when the data was collected and when it’s being analyzed. If the data has been collected and analyzed in real-time (within a few days or weeks of the assessment) the results of the data analysis may be immediately applied. This is most commonly seen after analyzing in-class formative assessments, exit tickets, or in-class tests or quizzes. Teachers can use the findings of their analysis to identify the needs that emerged and course correct for their students in real time. It’s not uncommon for data analysis to take place well after the assessment was completed. This is especially true for state tests, national diagnostics, or other formal assessments. When several months or more have passed, the data becomes more like an artifact from the past, rather than real-time information of what specific students know and can do. Artifacts can be extremely insightful and help us to see patterns and trends that might have been obscured at the time the assessment was taken. When looking at data collected in the past, we can use it as a snapshot of a specific point in time and consider what is the same and what has changed since the data was collected.

Whose data is it?

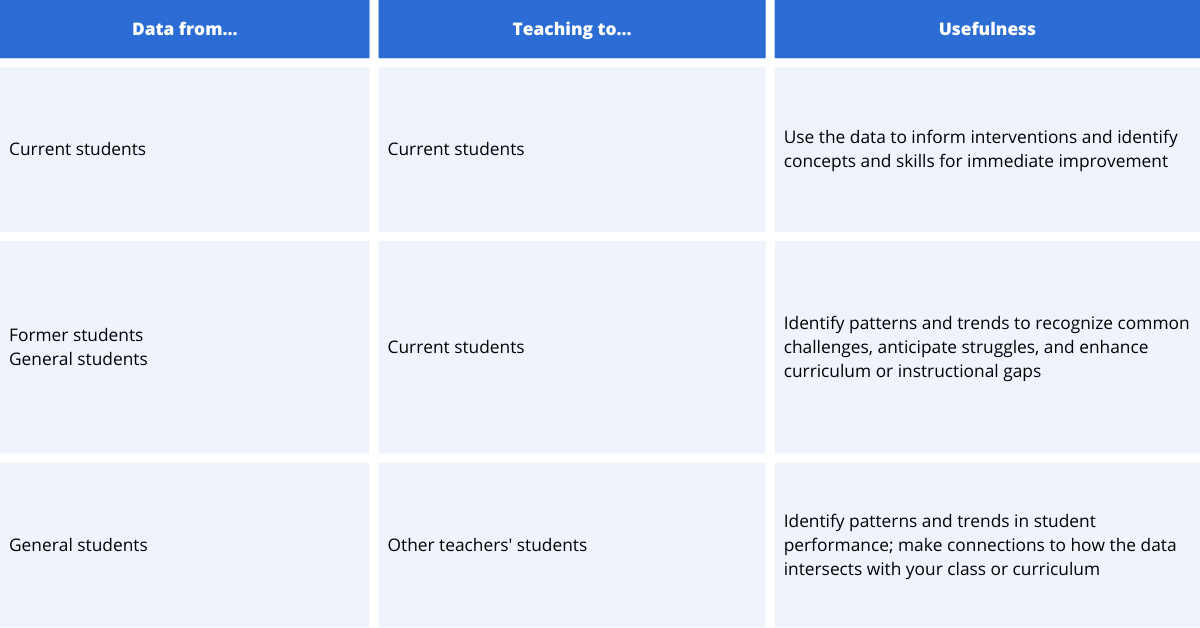

Next, we want to consider whose data we’re analyzing. Are we looking at current students in our class, who we’ll see in person within the next week? Are we looking at former students who’ve left our class and have moved on to their next learning experience? Are we looking at a larger picture of students we’ve never taught before and aren’t likely to encounter personally? When thinking about the “who” of data, we want to consider the students whose performance generated the data, who we’re teaching now, and how understanding the data will help us refine our practice for our current students, even if we never taught the students whose data we’re analyzing, and we never will. A helpful paradigm for this might be, data from... and teaching to…

Analyzing multiple choice data

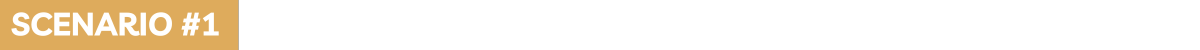

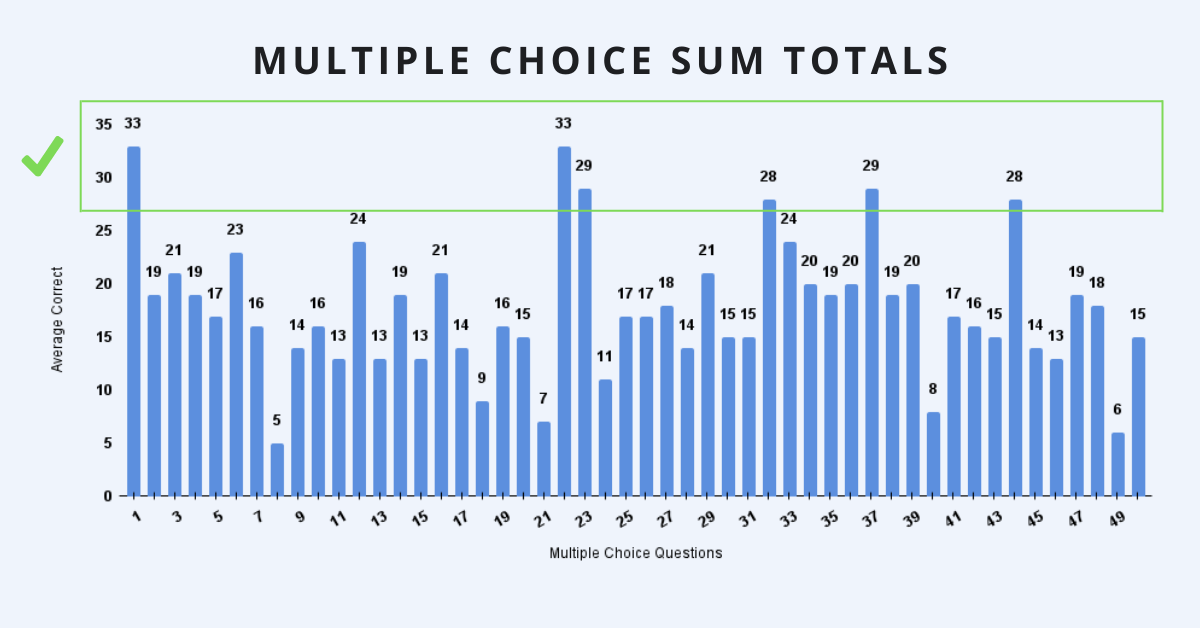

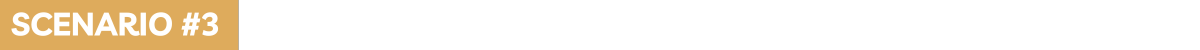

Once we are grounded in the basics — when we understand where the data comes from, when it was collected, and who our instruction is targeted towards — we’ll have some direction and purpose for looking at multiple choice results. To make sense of the data, and to use the information strategically, we can consider our next steps based on the following scenarios:

75% or more students answered a question correctly

DATA FROM...

Whether it’s a spreadsheet of numbers or infographics that reflect the data in charts or other visual models, one of the first trends to examine emerges with questions that most students (75% or more) answered correctly. These questions help us to identify the key content or skills that are present in the curriculum, and were taught so effectively that most of the students in the cohort were able to answer correctly during the exam. CRITICAL QUESTIONS When we’re analyzing the data to inform our future curriculum mapping and instruction of students in the future, we want to reflect on where and how these concepts show up in our curriculum and put a star next to them. We may examine the instructional methods that were used here and see if we can expand these practices to other topics in the course. As we review these correct answers we can ask ourselves:

TEACHING TO... If we’re analyzing data from current students, in preparation for these students to take the same or similar exam again in the future, we’ll also want to take a close look at the students who got these questions wrong. Narrowing down that <25% of students who answered the questions incorrectly, when everyone else in the class answered correctly, helps us to identify students who are in need of an immediate intervention. These questions reveal that while everyone else was able to learn and apply the content taught in class on the test, this group of students continued to struggle. These concepts won’t be a good use of class time to review for all students, but with the data we can identify the specific students who will benefit from some increased support and reflection on their learning.

75% or more students answered a question incorrectly

DATA FROM...

After reviewing what most students answered correctly, we can then turn our attention to where most students answered incorrectly. When 75% or more of our students got the answers wrong, it does point to a potential gap in our curriculum or instructional methods. CRITICAL QUESTIONS As we review the incorrect answers, we can ask the same questions as before:

Our answers to these questions will reveal topics that perhaps we didn’t cover but needed to, or places where maybe our instruction was rushed or hurried and students didn’t have a memorable experience to take with them into the exam. When we analyze the data to inform our future curriculum mapping and instruction, these questions will help us better understand where we need to make revisions to the learning sequence, pacing, or focus in our future instruction. They may reveal instructional strategies that were less effective, or a change in the assessment expectations that can be translated into curriculum planning. TEACHING TO... When analyzing the data to inform current instruction for students who can retake the exam, these questions reveal the topics or skills that the whole class would benefit from reviewing or re-learning. More specifically, when we examine the specific answers the students gave (did everyone choose the same wrong answer? Did they choose different wrong answers? What does their response tell us about their misconception?), we can identify misconceptions and use that information to focus our instruction moving forward.

50/50 split between correct/incorrect answers

DATA FROM...

The third step for analyzing multiple choice data is to examine the questions that split our class into two groups. When around half of the class got the question correct, and the other half got the question incorrect, the question highlights content and skills that often mark the difference between students who are just barely passing or just barely failing. Since we see that at least half of the students answered the question correctly, we can have some assurance that this content was taught, but that not all students were able to internalize the concepts or recall them on the day of the test. CRITICAL QUESTIONS When we encounter these questions we can ask:

TEACHING TO... When analyzing the data for current students who have an opportunity to retake the assessment, it is useful for students to reflect on their responses and have another opportunity to resolve misconceptions. When analyzing the data for future students, these questions are triggers for content that needs more time, differentiation, or strategic instruction. These questions are key for seeing the tipping point between students who are meeting exam expectations and students who are close to doing so, but can’t quite make it yet.

When we take time to analyze student performance on an in-class assessment, state exam, or national diagnostic, we’re really taking the time to invest in our own learning. The more we can identify, recognize, and even predict the patterns and trends in student performance, the more we have to work with when we’re in the planning process.

Beyond simply helping us develop more effective curriculum maps and instructional methodology, data offers us the opportunity to use this information with current students who will be retaking the exam in the future, building a blueprint of concepts and skills they need to develop in order to meet their target goals. Examining the data from all three vantage points gives us the perspective we need to make strategic choices in the future.

Help students build stamina for homework by creating a consistent, meaningful structure for assignments.

While there are a range of positions on the benefits and drawbacks of out-of-class learning (aka homework), many teachers recognize that learning outside of class can benefit students as they develop new skills. Research shows that student engagement and performance increases when students engage in meaningful, relevant, out-of-class opportunities aligned with the in-class curriculum. Additionally — and especially in high school — out-of-class learning is important for students to gain valuable college-ready study skills, move through content at a faster pace, and develop personal responsibility and executive functioning skills.

While many teachers see the value of out-of-class learning, the challenges around homework are so overwhelming that assigning any homework at all can feel like a lost cause. We often assign homework as a way to build healthy academic habits for students to develop independence and personal responsibility. But building habits takes time and consistency. This means that in order to create a learning community where students regularly and reliably complete their homework, it must also be assigned consistently. Whether it’s assigned on specific days of the week, or in a set pattern, establishing homework routines and sustaining them for long periods of time is essential for developing the habit forming behaviors that students need to engage in their learning outside of class. Consistency is critical — but consistency without purpose can lead to its own set of challenges. In an effort to create routines for homework, we sometimes fall into the trap of assigning homework for the sake of assigning homework, rather than for engaging students in meaningful practice. But when students can’t find the purpose or the relevance between their homework and the classwork or their own interests, they will lose a sense of purpose and their participation will begin dropping off. Homework should build a bridge between students’ lives and content topics in the classroom. Disconnected tasks have no impact on students’ understanding of the content, engagement in the course, or in developing the long-term characteristics of independent learners. When out-of-class learning is disconnected from the in-class content, it loses its value both to the student and the teacher.

Creating consistency & meaning

There are four types of meaningful homework assignments: Practice When students apply a concept or skill learned in class. Practice assignments engage students in reading, writing, or problem-solving tasks that they’ve learned in class and can apply through different examples. Practice tasks help students internalize the concepts and skills, and encourage them to think through a variety of applications. Common practice tasks may be reading with a graphic organizer or notetaking protocol, completing a problem set, or strategic vocabulary building. The benefit of practice tasks is that the reinforcement helps students internalize content they’ve learned in class, which should better prepare them for new content in follow up lessons. Extension When students take something they’ve learned in class to a new application or new context. Extension activities take in-class learning to a new level, stretching students to think about the concepts in different contexts. This might look like extending an application task in class to an analysis level or to a synthesis level outside of class. It may be asking students to make relevant connections between class content and their own lives, or drawing real-world conclusions on a given topic. The benefit of extension activities is that they help students see their classwork as relevant or important in the real world. Preparation When students engage in learning that prepares them for in-class content. Preparation activities provide students with the prior knowledge, skills, or context to prepare them for future classwork. This might look like including a pre-reading activity, or review of prerequisite information needed for the in-class task. When developing preparation activities, consider what types of tasks will help students engage in future tasks, avoid creating in-class learning that is 100% dependent on completed homework. Creative When students use personal expression to respond to in-class content or other learning goals. Creative tasks are activities that go beyond recall or critical thinking and invite students to synthesize, reflect, or create a response to the topic being studied. These types of activities might include independent reading with a reading journal, personal reflection, drawing, or modeling a concept through multiple modalities.

Creating a structure

If it’s been difficult to establish a learning environment where students regularly engage in completing tasks outside of class, it can feel pointless. Unclear how to make a culture shift for our students, we can feel really defeated and give up even trying. But if we’re serious about cultivating these skills in our students and we know it will be better for their learning long term, we can make strategic choices to help our students develop important habits over time by leaning on some of the principles that drive athletic trainers to help people develop healthy physical habits. In the sample homework sequence below, we can see how it would be possible to take students who haven’t done any homework all year through a process that would build to 30 minutes of homework within 8 weeks, using six principles that provide structure for a goal-oriented routine, and translate from physical habits to academic habits.

Creating the right conditions for change

Periodization We respond to patterns and cycles that help to structure consistency & variety. In athletics, periodization may look like alternating weight training with cardio to develop a balance of strength training and heart health. In teaching, periodization is about creating a balance of interesting and relevant activities so that students don’t get bored or burnt out after a few days of practice. Creating a schedule, routine, or pattern for homework tasks is a great way to build in periodization. Reversibility Our practice will reverse if we’re inconsistent. When engaging in skills-based activities, consistency is critical for establishing healthy habits and meeting target goals. When we’ve established healthy habits, the tasks are easy to complete and bring satisfaction. When we are inconsistent, our skills atrophy, and it can take a lot more mental energy to get back into the habit. The same is true for homework practice. When we’re inconsistent in assigning homework, students will fall into reversibility, and it can set their progress back to the beginning stages. Consistency is critical for success. Specificity We can maintain interest and balance by rotating through a variety of tasks. If we went to the gym every week and lifted 2.5 pound weights, we might see a jump in our strength in the beginning, but if that’s the only exercise we ever do, we’re likely to see those early gains fade away. Just like the body gets used to the same physical activity, the brain gets used to the same mental activity — and it loses its potency after a period of repeated use. This is tricky because we know we need to engage students in consistent practice, but that consistent practice must include a rotation of different thinking routines in order to maintain interest and balance. Progression We need to evolve our training needs over time to keep a consistent level of challenge. Similar to specificity, progression is about ensuring a consistent challenge. In physical fitness, this means that as we get stronger, faster, or more agile, we move the target to increase the challenge. Similarly, with our students we want to ensure that as their skills improve over time, we continue to increase the intellectual challenge so that students’ interest, curiosity, and skills continue to increase over time as well. Overload We will benefit from instances of “maxing out” or a” big stretch”. For athletes seeking a physical target, they create opportunities for overload, to periodically see how far they can stretch their skills. The concept of “maxing out” is about going as far as one can go to measure the extent of progress. Maxing out is not advised as a daily or even weekly routine, but rather as a periodic test designed to assess progress and set up parameters for a new training routine. The same can also be valuable in pushing students to new levels in their academics. Engaging students in progressively challenging content, texts, or problem-solving activities can stretch what students thought they were capable of and paint a picture of what’s next in their learning. Overload doesn’t just create a stretch for the next training level — it also changes our perspective. When an athlete routinely lifts 25 pounds each workout, and then maxes out to 50 pounds, lifting 30 pounds the next session will feel lighter. Similarly, when students engage in reading a complex text or completing an intense multi-step problem and then return to a text at their level or to a problem with a recognizable solution, their own confidence and perspective also shifts. Individualization We each respond to challenges differently. While we can recognize that there are some workout patterns that can be a helpful guide, everyone is unique and responds to stress and challenges differently. Whether they’re physical or intellectual challenges, we need to consider and plan for meeting students’ individual needs. This comes with talking openly and directly with our students about the tasks, what we’re doing, why we’re doing it, and how it can help them reach their own goals. Additionally, it comes when students engage meta-cognitively in their own practice. How are we engaging our students to reflect on their challenges, their fears? How are we helping them develop tools that can empower them to strive toward their goals? We strengthen our students when we engage them in action planning, personal goal setting, tracking progress, and celebrating small and large successes.

Creating a culture change with respect to working outside of the classroom can be overwhelming, but it’s not impossible. With a strategic plan that engages students and focuses on building strong habits over time, we can cultivate a community of learners who develop personal responsibility and independence over time.

Create a space where each student sees themselves as someone who belongs, someone who matters, someone with value.

This article is part of our Close Up On CRSE series

One of our core principles is rooted in culturally relevant, responsive, and sustaining pedagogy. We understand that we can’t separate an individual’s identity from their history, their language, their culture, beliefs, or values. As human beings, when we feel seen, heard, and valued, we are more open and engaged. It’s easier for us to feel safe, take intellectual risks, and be open to making mistakes. This is why creating a “Welcoming and Affirming Environment” is the first principle in many CRSE frameworks. But what does that mean, exactly, when it comes to classroom teaching, and what can educators do to create this kind of space?

Building a sense of belonging

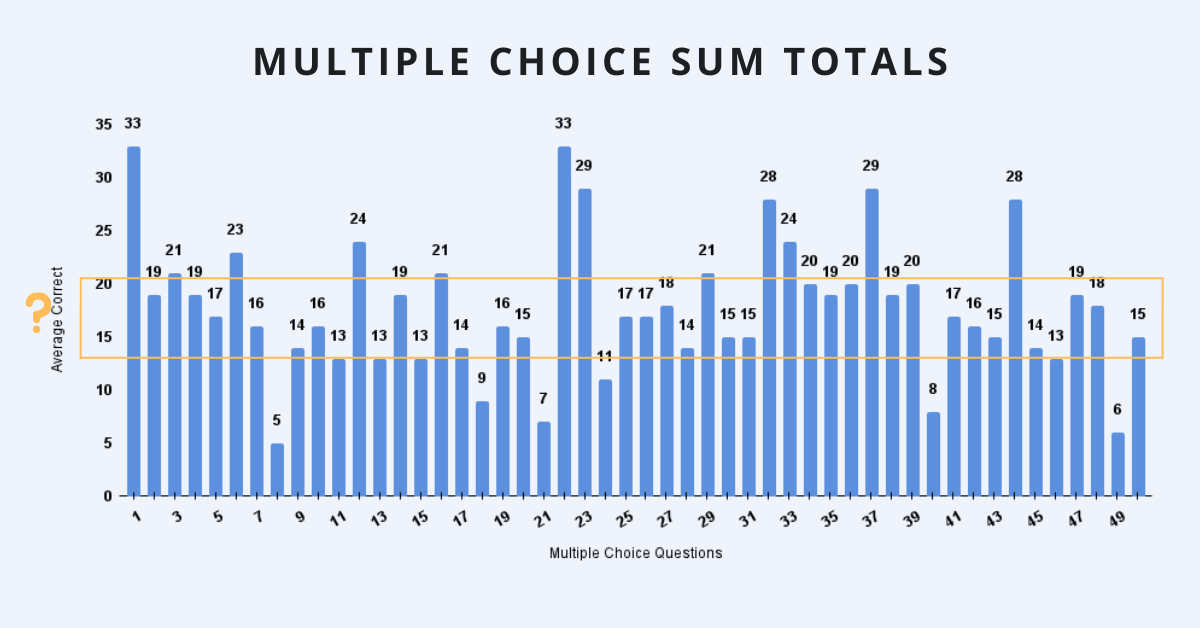

In Centering Students: A Deep Dive into CRSE-Aligned Practices — a guidebook we co-designed to analyze CRSE principles and attributes — we investigate what CRSE looks like in practical, pragmatic terms, in the real world. Let’s take a close up look at Welcoming and Affirming Environments: Affirms Diverse Identities.

The notion of an affirming space is important within this attribute. We think about affirm as distinct from tolerate — as in, to acknowledge something exists even though we may not appreciate or approve of it. Affirm is also distinct from accept, which again means we simply acknowledge that the diversity may exist, and may or may not take a stance on whether or not it is of value. To affirm is to be overtly clear that our students are welcomed and valued, and since we cannot separate the individual from their identity, it means their cultural background, spoken languages, values, and beliefs are also welcomed. The NYSED CRSE Framework corroborates this concept by stating that schools are “a space where people can find themselves represented and reflected,” and the CASEL Social-Emotional Framework describes the importance of “integrating personal and social identities” as a critical component of self-awareness. As we describe it, these are spaces that integrate positive linguistic (language), gender, and cultural identities into classroom instruction (how we teach) and curricular materials (what we teach). Affirming diverse identities isn’t only about cultivating the social-emotional connections that help students feel a sense of belonging in the community. It’s also a key component of effective instructional practices, as outlined by the Danielson Framework. Danielson’s domains in content & pedagogy and classroom environment state that “teachers convey that they are interested in and care about their students” and “students feel respected; their dignity is not undermined.” If we’re interested in maximizing learning opportunities for our students, then we want to be conscientious of the benefits of belonging in the learning community. This is true for all of us, but especially for students who identify with cultures that are underrepresented. There is no recipe for affirming student identities, but there are many small entry points that we can locate as we explore small ways we can proactively affirm students’ identities and create a community that celebrates diversity.

Get curious

When making an effort to affirm identities, words matter. It isn’t enough to simply be non-offensive, especially in spaces where we have a historical backdrop of negative bias. What actions can we take to accept and respect who our students are, and build positive connections with them?

Words matter:

Get concrete

How can I acknowledge and affirm the languages represented in my class?

How can I acknowledge and affirm the language my students’ families speak?

How can I affirm youth language in positive ways?

How can I set norms for student-to-student communication?

Get clear

When we observe or overhear students (or adults) using offensive or harmful language or behaviors, it can be a surprising and disorienting experience that sometimes creates an instinctual flight, fight, or freeze reaction. If we can get clear about the ways we will treat our students, and how we expect them to treat one another, we can prepare our responses when harmful ideas are brought into safe spaces.

We want to maintain a grounded presence and offer clear guidance that helps students course correct and that diffuses any potential conflicts. We recommend that teachers work in collaboration with co-teachers or teams to develop a response plan so that when these moments arise, they can be addressed quickly and consistently across classrooms. Whether you’re creating your response plan individually or with a group, here are a few things to consider:

Depending on the situation, addressing harmful language and behaviors can be a simple reminder of the expectations, or may need more in-depth support for conflict resolution or personal reflection to better understand the harm that’s been caused. Work with guidance counselors or social workers to support these more serious situations.

Affirming diverse identities is a challenge to see our students beyond where they sit, the clothes they wear, or their latest hairdo. It’s an opportunity to get to know them beneath the surface, and the privilege to create a space where they see themselves as someone who belongs, as someone who matters, as someone with value.

When they experience this level of community-building, it’s easy to learn.

Five considerations for creating a student-centered grading process that helps boost confidence and reduce confusion.

When I ask teachers what drew them to the profession, I often hear stories about a teacher who believed in them when they were a student, a subject area they became passionate about, or a love of children that has brought them to the classroom. I have never heard a teacher list “grading papers” or “filling out marking period grades” as a driving factor in choosing teaching as a profession! However, the process of grading is often mentioned among the biggest stressors in the job.

The subjective nature of grading puts teachers in a somewhat impossible position. Every school has a different grading policy and different levels of internal and external accountability, and most teachers determine grading in isolation, sometimes late at night with eyes drooping from exhaustion. Teachers are responsible for selecting tasks, the value of those tasks, the right answer(s), the grading scale, and the overall worth of each assignment — all while knowing that once their (rarely reviewed or audited) grades are submitted, they create a powerful narrative about students’ identities as learners. Even though grades are such a high-stakes component of a teacher’s professional responsibility, the topic rarely shows up in teacher training courses, licensure programs, or even in school professional development sessions. This leads to a wide range of grading philosophies and practices among teachers, even those within the same school or discipline. This is because there isn’t a single, simple formula to translate dynamic learning into a static number. It’s a lot harder than it looks, and to do it well takes critical reflection and deep content knowledge.

Grading pitfalls

By the time grades hit a student’s final transcript, they’ve been totaled and averaged and weighted and averaged over and over again. But no matter how long the process takes from student work to official transcript, how we evaluate students should be based on a fair evaluation of how students demonstrate their learning — and in order to grade fairly, there are common pitfalls that should be avoided.

Grading can be a trying, tiring, and tedious task, but we can identify some F.A.C.T.S. about grading that can help keep us grounded, and our students engaged and motivated to learn.

Fair

Fair grading systems mean there is a rationale behind the value of an assignment, how many points/how much weight it has in the gradebook, and that there are clear criteria for its evaluation. This might mean teachers have developed a rubric, checklist, or explicit expectations that have been shared with students in advance. When students demonstrate a misunderstanding with incorrect or incomplete responses, teachers should be able to identify where they lost points, and why. If students or families ask questions about the way an assignment has been graded and the teacher who designed the task isn’t able to answer them, it’s a sign that this assignment needs more attention to determine the clear expectations and criteria for success.

Accurate

Accurate grading systems use a consistent measure over time, and have a method for translating that measurement into the school’s selected grading metrics. Whether the school is using the letter scale (A, B, C, D) a numeric scale (1, 2, 3, 4), or a traditional percentage (90%, 80%, etc.), the teacher has to think through how their assignment will ultimately contribute to this evaluative measure. If I grade daily assignments with ✓s and +s, I have to devise a way to translate those symbols into numbers on the final grade. If I don’t, or if I don’t do so consistently, then my grades are not accurately representing what students know and are able to do. Accuracy also counts when it comes to task design. If I set out with a policy that all classwork is equal to 10 points, but on Monday the classwork is worth 10 points with 5 questions and on Wednesday the classwork is worth 10 points with 20 questions, we may have an issue of accuracy in the grading process. The best way to design an accurate grading system is to plan in advance the types of tasks that best represent student learning, and identify their value and weight as they relate to how students demonstrate that learning. Then, implement a system that makes it easy to translate learning into the metrics and measures that your school has selected.

Consistent

Students (and their families) look to their grades to measure their progress in real time. Especially with the nature of gradebook software that allows students, parents, and teachers to log in day or night to track their progress, keeping consistent grading practices is critical for keeping students engaged and on track. When the gradebook significantly lags behind real time, students can get a false perception of their performance, which may impact their day-to-day choices. Some grades may appear high when in fact they’re slipping below the passing line, while other grades can take a nosedive overnight and sound the alarm bells unnecessarily. When students’ grades change faster than soap opera characters can die and come back to life, it can create a similar level of conflict and tension. The hardest scenes to watch are when students become so frustrated that they can’t see the impact of their hard work on their day-to-day grades, and they lose trust in the system; this is when a cycle of failure can set in. Students who don’t get consistent feedback on their progress can begin to feel that the work isn’t worth their time, reduce their effort, and subsequently see their grades slip. As they get more and more discouraged, they may miss their chance to turn things around before it’s too late. While we can advise and support students to understand the grading system and keep track of all of their assignments, it’s our responsibility as the teachers who design, assign, and assess the tasks to be clear and consistent in our practices.

Transparent

Fair, accurate, and consistent grading methodologies should also be transparent to students, colleagues, parents, and school leaders. If we want students to succeed, we should not stay silent about what it takes to reach academic goals! Creating transparency is about being clear, explicit, and forthcoming about what needs to be done in order to succeed. Transparent grading practices include providing explicit grading criteria and guidelines in advance. This might be a rubric that students review alongside a teacher at the beginning of a project, or a checklist of expectations and their point value, or even including the number of points possible/earned on each assignment. Students who don’t understand how their grades are calculated are less likely to see the connection between their hard work in school and their grades, which means they’ll also struggle to see the connection between their grades and future opportunities in life. We can be proactive by being clear with our students about our grading practices and policies, but we can also empower our students to be their own advocates. By engaging students in keeping their own gradebook, self-assessing their progress, assessing peers in group work, and hosting grading conferences, we can take the mystery out of the marking period and give our students all of the information and tools they need to maximize their grades.

for Students

When the class is over at the end of the semester or the school year, the grade is the only thing that’s guaranteed to remain. For students in high school, grades represent their identity as a learner as they share their transcript with potential colleges, write their GPA on cover letters and resumes, or seek scholarships and grants. Grades are high-stakes, and as teachers we have a lot of power over how students move through school and how they’re perceived along the way. Often, grading is perceived as something for the teachers’ benefit, or for parents — but all grading is for students. When we position students as the ultimate stakeholder for grades, we are able to leverage grading systems to increase a student’s personal investment, empowerment, and agency over their learning. When grading becomes a way for us to encourage our students with actionable feedback and notes about how they can adjust their performance to reach their goals, the grading process ceases to be tedious recordkeeping. Instead, it becomes a critical conversation about content knowledge, critical thinking skills, progress, and performance over time.

How the timing of checks for understanding can impact what you learn about student comprehension.

Great teachers want to be sure their students understand content information on a daily basis. They don’t want their students to wrestle with misconceptions, misunderstandings, or mistakes in their thinking that might set them up to struggle as the content unfolds throughout a lesson or unit. As a result, many teachers use small, formative assessments at the beginning, midpoint, or end of a period so students have an opportunity to practice their content and skills, and teachers can assess their understanding at different stages of the learning process. In an effort to ensure that all students have the right answers and a clear understanding of the lesson, many teachers review the correct answers to the assessment before moving on to the next stage of the lesson.

In both examples, we see the teachers making choices that elevate student collaboration, ensuring students have the opportunity to correct misconceptions, connect with one another, and leverage grouping and discussion strategies to process content information. In both examples, the teacher is using a formative assessment — or a check for understanding — with the goal of assessing student comprehension. And in both examples, the check for understanding may be giving teachers more misinformation, than information.

Check for understanding

Well-developed instructional design includes multiple checkpoints to assess student comprehension in real time. Highly effective assessment structures may include between 1-3 checks for understanding in a class period, with each check being an opportunity for students to independently demonstrate their understanding and skills related to the lesson objective or learning target. When we jump from the check for understanding task to the review of direct responses, some unintended consequences may emerge. One likely scenario is that students who had a misunderstanding or a misconception when working on their own will likely copy down the “right answer” during the discussion. But copying down the answer doesn’t necessarily correct their misconceptions. The unintended consequence is that it appears that all the students have the correct answer, even though some may have simply copied down the answer during the discussion. For teachers using formative assessment data to inform their instructional choices, there’s no evidence that helps them know which students had the correct answer at the time of the assessment, which students had an a-ha moment during the discussion, and which are copying down the correct information but are actually still confused. Another unintended consequence is that students discover that the right answers get shared immediately, before their work is completed. It’s a lot easier to copy down the right answers later than it is to work through the hard problem in the moment. Some students may begin to opt out of the learning activity altogether and simply wait for the correct answers. This phenomenon may not be noticeable right away — a gradual disengagement happens slowly over time, and can start with students who appear slow to start, or students who are easily distracted. For teachers feeling the pressure of time, it can be tempting to skip to the right answers even if some students aren’t finished. The challenge is that over time, fewer and fewer students finish the task because everyone is waiting for the right answers to be shared.

Creating space for small changes

The good news is that there are a few small changes that can make a big difference. Add a reflection. In addition to the discussion of the correct answers, ask students to write a reflection comparing their first response to the correct answer, and share if they made any changes to their thinking or had any a-ha moments in the process. Consider creating a chart on their task that includes space for their individual work, notes from the discussion, and reflection after the discussion. Not only will this provide more insight for you as the teacher, but the students’ metacognition will increase their self-awareness, which supports recall in the future. Have students share & give feedback. The standard share out often includes time for students to work independently, followed by the teacher reviewing the correct answers. This practice can be modified to having students post their answers in small groups at the same time, and then visiting other groups' responses and leaving feedback or asking questions. By turning this process over to students, teachers can increase the responsibility and accountability for students to work with their groups and think critically if different groups have different responses. Leverage differentiation strategies. Building in differentiation as a result of a check for understanding is an effective way of structuring the lesson. Teachers can plan to use hinge point questions, where students receive a specific task as a result of their answer on a check for understanding question, or Four Corners, where students move around the room in real time to show their thinking and discuss with their peers. Both of these strategies leverage real-time responses and interaction to notice misconceptions and work to address them in the moment.

Checks for understanding are a very valuable touchpoint. Getting in the moment information about what is and isn’t clear for students provides insight into differentiation, student grouping, and tweaks to the next day’s lesson. When we reveal the “right” answer before we can gather information on what students know and can do, we might go for weeks before we realize that students have not been learning what they need to be successful on high-stakes assessments like unit tests, projects, or major exams.

It’s true: it is important to correct misconceptions, and we don’t want students to sit in frustration if we’re withholding information that can help them learn. And also, when we jump to reviewing the right answers before we’ve had a moment to collect the data or reflect on how students are processing the information in the lesson, we miss valuable insights that help us plan and prepare the learning pathway for students’ success.

Replace antiquated advice with new norms that value your humanity.

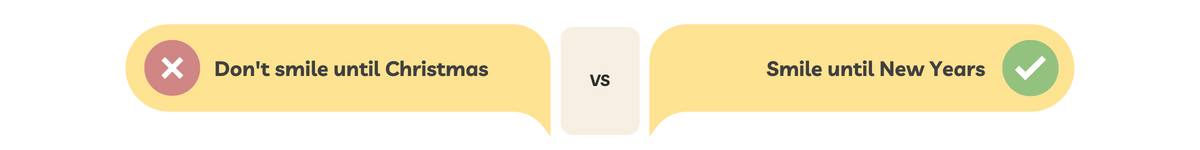

Don’t smile until Christmas.

Never let them see you sweat! Fake it ‘til you make it. Advice to new and returning teachers about how to start the school year is as ancient as the Greek and Roman myths that start with Chaos and bring forth Zeus, Poseidon, and Athena. But these gods of lightning, storms, and war have little place in the 21st century classrooms. And many of these words of so-called wisdom are from a time when the culture valued a teacher-centered dominant force in the classroom. But we know better now. Now, we know that students learn best in an affirming environment that becomes rich with diversity, dialogue, and shared decision-making with students. Research shows that students become more engaged in their learning experiences when they can use their voice to cultivate their agency. This happens when they are given the opportunity to reflect and discover their opinions, share their perspectives with the people and structures in power, and when the system incorporates these new ideas to create change. The major shifts that come from centering students — rather than centering teachers — change how we structure our classroom spaces and how we show up in that space together. Teachers are culture creators and everything we do, especially at the beginning of the year, sets the tone, the mood, and the rhythms that eventually become the core of our learning community. How we show up has a major influence on whether that space is helpful or harmful. If we choose to let go of the ancient myths, we can replace them with new norms that help us invest in our students and in ourselves.

"Don't smile until Christmas"

Old myths focus on behavior and compliance, rather than ways we can leverage learning. Yes, we need students to follow common school structures, but good behavior doesn’t mean increased learning or engagement. If we can move away from compliance and refocus our energy on creating a culture of learning, we’ll get something better than compliance: collaboration and engagement. But what does that look like?

In his book, The Culture Code, Daniel Coyle breaks down the concept of “belonging cues.” These are the small verbal and nonverbal ways we interact with people to signal to them that they either belong, or that they don’t belong. These cues are powerful in peer group dynamics, but they’re even more dramatic in power dynamics such as classroom spaces. When the teacher leads interactions with signals of belonging, it makes students feel like they’re in a welcoming and affirming environment, which lessens anxiety, increases openness, and clears a pathway for connection and learning. There isn’t a magic list of belonging cues, but a few easy to implement strategies can include:

"Never let them see you sweat"

The idea that the teacher is the sage on the stage and the holder of all knowledge is impossible to uphold — and presents a false notion that knowing everything is something to strive for, much less something that’s possible.

When students buy into the myth that their teacher knows everything, they can feel insecure because they know how much seems unknown. This dynamic creates a sense of helplessness and sets up a fixed mindset that positions knowledge and intelligence as something that someone is born with, rather than something they work hard for. We can disrupt this myth by being our authentic selves, and by talking with our students about what we know, and what we don’t know yet — especially if they’re posing questions that we don’t really have the answers to! When we encounter something that’s beyond our knowledge base or skill set, rather than pretending to be cool and never letting them see you sweat, we can be honest with our students that learning is a process that never ends, and the smartest people know how to learn. Then we can engage together on the journey to answer the open questions, explore a new line of inquiry, or use our resources to check our understanding and accuracy. We can say things like:

"Fake it 'til you make it"

Imposter syndrome is a well-documented phenomenon that can become overwhelming to anyone who’s learning on the job. At the beginning of the school year, or when starting a new role, this syndrome can hit hard. In the past, the remedy for imposter syndrome has been the myth fake it til you make it! While it’s important not to let our fears and insecurities paralyze us from moving forward in our work, it’s counterintuitive to think that the antidote to feeling self-conscious about our skills is to go it alone and not talk to anyone.

Everyone needs a network of support, and not just when we’re struggling. We can curate our networks with mentors who’ve walked the road before us, peers who are able to walk alongside us, and even with folks who are novices compared to us. This might be a formal network that meets regularly, or an informal list of people you reach out to. It’s easy to fall into the fixed mindset that we’re either good or bad at our job, but this is false, and frankly, toxic. Teaching is an art, a craft, a science, and practice — it’s not magic. No one has it all together and the best teachers are the ones who ask for help, learn from others, and pay it forward.

There is a time and place to tell tall tales from the age of yore. But as we push into the third decade of the 21st century, let’s be clear that some of these myths aren’t just outdated, they represent a harmful and dysfunctional way of working. They distort the truth about the challenges of teaching, and they can perpetuate feelings of isolation and fears of failure for teachers and students.

These new norms for starting the school year are about making an investment in the humanity, validity, and inherent worth of each person because we learn better — and we teach better — when we can be our whole selves.

Prompt new perspectives for the year ahead using one simple sentence.

Any way you look at it, the last two years have been very different from anything most of us have experienced, upending the way we teach, the way we live, and the ways in which students learn. These years have revealed vulnerabilities, punctuated inequities, and surfaced extraordinary human resourcefulness and potential. Many of the decisions made within this time will have long-term consequences for the future of education, and we are likely years away from understanding the full social-emotional impact for teachers and students.

Before going any further, we have to give a huge shoutout to all the teachers, school leaders, parents, extended family members, and friends who continue to contribute time, patience, perseverance, and ingenuity as they help children learn. We have been navigating uncharted territory for an extended period of time, and in the face of numerous challenges, you have continued, time and again, to step up in support of students.

Prompting new perspectives

As we come to the close of another school year, we’re at a natural checkpoint for reflection where we can consider the year’s successes and missteps, and think deeply about how our experiences this year can inform our actions in the next. Whether or not you have been practicing regular reflection this year, it’s never too late to start! One of our favorite ways to check in after a meaningful experience is to use the prompt: I used to think, but now. This exercise provides an opportunity to reflect back on where you started — whether that’s at the beginning of the school year, the semester, or any marker of time that’s relevant to you — and evaluate how your thinking has changed since that time. Your responses might look something like this:

Because critical reflection is, well, critical, you can also use this sentence starter to reflect on work/life balance as you think through ways to find space for self-care, create time for outside interests, or unpack personal challenges. I used to think, but now is powerful because it challenges us to identify a point in our lives where we’ve changed our minds or had new learning, but haven’t yet explored or processed this transformation. By spending even just a few minutes responding to this prompt, we can make our realizations concrete and explicit — and that will help us to internalize these life lessons for the future. This is also a great strategy to share with other adults on teacher teams, or with students. Even young learners can follow along to reflect on what they’re learning and how their perceptions are changing throughout the year. Take this practice one step further by asking yourself how your shifted understandings or beliefs will impact your practice in the coming year. What will you do differently in the future? (We call this one, “I used to think, but now…and so…?”)

Reflection is an ongoing process — we continue to learn lessons each year because we are different, our students are different, and the world around us is different. Finding moments to reflect on all we’ve learned and reset our expectations for the future is crucial in order to meet ourselves and our students in the current moment.

Tell us in the comments: how would you respond to I used to think, but now?

Why creating intentional groups can help match each student to intellectually engaging tasks.

Group work is important.

Group work is also hard. It can feel discouraging when we initiate group work and then it doesn’t go as planned, with some students opting out of the assignment while others carry the weight of the task for everyone. Teachers know that when they have a wide range of students with different learning needs, they can differentiate their instruction. Differentiation often includes creating multiple entry points to content and skills through group work, and we often see differentiation strategies like heterogeneous or homogeneous grouping used to differentiate instruction. But how do we determine which method will help our students reach their learning goals? Which types of grouping are best for which instructional strategies?

The case for homogeneous grouping

Whether matching students in pairs or small groups, homogeneous grouping happens when teachers enlist students with similar learning traits to work together to complete a task (either individually or together). Homogeneous grouping should be informed by data, like students who earned similar scores on a diagnostic assessment, had similar responses in a class assessment, or who shared a misconception about a previous lesson. It's valuable to match similar students together to complete a task that is designed to meet their learning needs. Homogeneous grouping is ideal when the teacher has designed a unique task for each group, is providing a unique text for each group, or has differentiated the content so that groups are aligned with content information they need to examine more closely. When students are in homogeneous groups, the tasks, topics, or texts they work with should be diverse. This becomes an effective practice because teachers are strategically matching similar students’ with a task that is designed specifically for them. When each group of students is working with a task or topic on their level, they’re able to increase their completion rate, feel confident about reaching their learning goal, and refine their thinking through discussion.

Example

A math teacher realizes that their students had a wide range of responses to adding and subtracting fractions on a formative assessment. Some students are completing all of the addition and subtraction questions with fluency and accuracy. Other students are struggling with subtracting, but showed proficiency with addition, while others are still struggling with the concept of fractions as well as how to add and subtract. With students performing within these three profiles, the teacher develops a lesson where students are grouped homogeneously and matched with a task that is specific to their learning needs:

By differentiating by student need in homogeneous groups, the teacher is able to match a task strategically to students in their zone of proximal development, which should increase their understanding of the content, create opportunities for success, and increase confidence.

The case for heterogeneous grouping

Homogeneous groups are an important strategy to use, but using them exclusively can be limiting to students. Not only is it important to develop community across a whole class, it’s also important for students to learn from one another and have opportunities to teach each other. Diversifying group structures to include mixed ability or heterogeneous groups gives students exposure to a wide range of voices, and keeps students connected to the class community. Heterogeneous groups are best matched with complex tasks that have multiple components. Within the group work structure, students can self-select or be assigned roles based on their areas of interest, as well as their performance. Working in a heterogeneous group allows them to build on each others’ ideas, and develop a product as a team, which is effective, memorable, and can be personally rewarding. Group roles or independent tasks are highly effective in heterogeneous groups and teachers will want to design the task so that every group member can take on a component that they can complete successfully. Jigsaw groups are a great structure to use for heterogeneous groupings. Within a jigsaw group, the group task is divided into multiple components (one for each student representative), and then brought back together when students inform their team of what they’ve learned. These components might be content-specific (e.g. each student represents a different character from a book, or a different type of problem solving in math). They may also be leveled by text (students divide out leveled texts on the same topic and collaborate on their understanding after reading). The easiest way to organize jigsaw groups is to strategically match students using a grouping strategy.

Example

If there are six groups, each student may be assigned a group number, and a letter which is matched with a task. Group 1 might have students matched with 1A, 1B, 1C, 1D, 1E, 1F (each letter representing a different task). Students then move into their letter groups (Group A would consist of students 1A, 2A, 3A, 4A, 5A, and 6A) and complete their task. Once they complete their task, students rejoin their number group to share what they’ve learned and complete the shared task or discussion. In heterogeneous groups, every student is matched with a task that is at their instructional level, and they use what they’ve learned to complete the shared task.

While homogeneous and heterogeneous groupings are some of the most common types of groups, they aren’t the only way to develop strategic collaboration for students. We can also consider grouping based on areas of interest, social dynamics, or even special gifts and talents. What’s most important is that when asking students to work together to complete a task, we are thoughtful and strategic about who should work together, what goal we want them to accomplish, and how we match them to an intellectually engaging task to reach that goal.

A flexible path toward mastery that provides structured support for students at all levels.

When I was growing up, my high school Social Studies teacher had a poster hanging on the wall that read, “If you think you can, or you think you can’t, you’re right.” The message was clear, even to teenagers -- the power to succeed or to reach a new goal is often inside of each of us. As educators, we know that our students’ mindsets play a major role in how hard they try, how much confidence they develop, and how committed they are to reaching their goals. But confidence alone doesn’t get them to a point of mastery. And desire alone won’t develop their skills, or increase their knowledge base, or level up their accuracy or precision. For those changes, our students need structured support!

This structured support often comes in the form of scaffolding. Like the large platforms that help construction workers reach the tall exterior of a building, scaffolding student learning creates platforms of support as teachers incorporate challenging texts, complex tasks, and abstract ideas into their instruction. Scaffolding is critical when holding high expectations and implementing a rigorous curriculum — but scaffolding alone doesn’t develop independent learners. Sometimes, scaffolding can become a crutch that teachers and students use, turning a support into a shackle. As educators, we often spend a lot of our planning time thinking about how to build scaffolds to break learning down into manageable components, but we can’t stop there. We must also consider the ways we gradually release scaffolding so that students can internalize and transfer their knowledge and skills to new tasks and topics.

A path toward mastery

Our Progressive Scaffolding Framework outlines a path for educators to consider when setting high expectations for students, helping them find that balance between necessary supports and structured enabling. Building on the ideas of Zone of Proximal Development and apprenticeship theories, the framework outlines a path toward mastery in four stages:

Stage 1: I do, you watch

When introducing new content or skills, we begin with the I do, you watch stage. We initiate this by introducing new concepts alongside prior knowledge, real world examples, or previous units of study. Our goal is to map new information onto our students’ activated schemas so that the new content or skills are contextualized and relevant. At this stage of instruction, we can prepare and provide a model of the task, using a Think Aloud mini-lesson where we walk our students through an internal thinking process that illustrates how we navigate the task and make decisions. Alternatively, we can outline the explicit steps to complete the task, or provide a roundup of the important information students need to know before diving in. The I do, you watch process can be presented to students working individually or in small groups. It’s important to remember that even at this stage, students shouldn’t be sitting silently. We always want students actively engaged, so we might add a note taking component, a reflection task, a meta-cognitive class discussion, or an element of inquiry so that students remain intellectually engaged in the process.

Stage 2: I do, you help

After laying the groundwork for the task in stage 1, we can move into stage 2, where students begin working with the content and task materials with support. Working in small groups, students might replicate the model with new information, restate or reword the essential steps in their own words, or engage in a small group discussion or group practice as a way to begin experimenting with and internalizing the skills.

Stage 3: You do, I help

In stage 3, the content and skills should be familiar to students after their initial explorations, and they should be ready to continue in pairs or small groups with more independence. Students are still in the development phase of their learning, so they may need additional support and will benefit from frequent check-ins, and suggested strategies — but here’s where we want to avoid returning to stage 1 supports. We’re looking for students to be engaged in a productive struggle. Students may benefit from suggestions of “fix up” strategies or options for what to do if they get stuck. At this stage, we want to push students beyond replicating the model or the example by having them practice the skill or apply content with a new format, a new context, or by making connections to other topics within the discipline or beyond. This is also a great stage to ask students to use one another as resources. While working in pairs and small groups is an excellent way to support students at their level and create opportunities for growth through collaboration, we want to ensure a high level of individual accountability so that some students don’t take on the burden for the group while others opt out of the learning process.

Stage 4: You do, I watch

In stage 4, students have been exposed to new content and skills, they’ve practiced working on a task informally with support, and they’ve begun making connections with other content information or demonstrating their learning through class activities and tasks. At this stage, it’s important to begin removing any unnecessary scaffolds to see what students can do independently. In the You do, I watch phase, we recommend providing a short review of the process and previous work done up to this point in the learning experience. After the review, we can be clear with students that they’re ready to try it out on their own. Provide a clear task and an adequate amount of time to complete the task (3-4 times as long as it would take you to do it). Students who are able to take on this challenge and demonstrate their skills individually prove that they’re meeting the expectations of the task and are ready to move forward to the next knowledge block or skill sets. Students who struggle at this stage help us to understand where and why they’re struggling, so that we can return to Stage 3 to provide targeted support.

How long does this take?

Like an accordion, this process can be expanded or compressed to meet the needs of your grade level and subject area. We might be able to move through the four stages within a single lesson, or it may be an expanded process that is organized across a week’s worth of lesson plans. Consider these two examples:

45-minute Lesson Plan Structure

5 minutes | Opening warm up: Inquiry question 10 minutes | I do, you watch: Mini-lesson modeling 10 minutes | I do, you help: Stop and jot, turn and talk reflection on the model 15 minutes | You do, I help: Small group practice 5 minutes | You do, I watch: Closing summary formative assessment

Week-long Lesson Structure

Monday | I do, you watch: Introduction, modeling, and reflection Tuesday | I do, you help: Small group discussion and practice Wednesday | You do, I help: Small group practice and connections, part 1 Thursday | You do, I help: Small group practice and connections, part 2 Friday | You do, I watch: Independent practice and formative assessment

The process of instruction and assessment is complex, especially when we’re trying to use data to inform instruction and support students who’ve struggled in the past. We want to be mindful to keep forward momentum toward rigorous learning goals while developing a clear path forward for students who begin at every level.

6/7/2022 Lessons from the Field: Practice and Professional Learning with the Global Mindset Framework

Making a 21st century skills framework meaningful for K-12 instruction.

Over the past century, advanced technology has made the world smaller and smaller. This has perhaps never been truer than the past decade, in which social media has made it possible for a tweet or an Instagram post to be seen around the world in mere seconds. Consequently, we see and have many more collective experiences. This was perhaps never more evident than over the past few years with the shared experience of a global pandemic and a rapid impact on learning in most parts of the world.

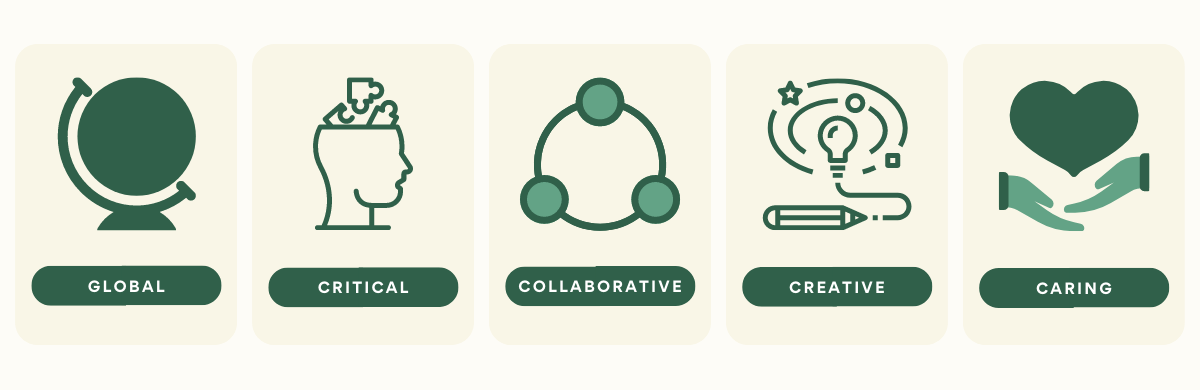

As we were thrust into new ways of thinking about teaching and learning, different mindsets, and different ways of imagining schools, we were faced with the truth that we can no longer sustain a 20th century in a 21st century world. The task before us is to educate students today for the world they’re poised to lead tomorrow. As a founding organization of the Global Learning Alliance (GLA), we have been thinking about reimagining education and preparing educators for the future for quite some time. The GLA is the outgrowth of our groundbreaking research in five of the top PISA-ranked cities around the world on the features and practices surrounding 21st century teaching and learning, and is committed to cross-cultural research collaborations as an effort to define a pedagogy that takes into account the dynamic needs of our changing world. Through this work, we are dedicated to understanding, defining, applying, and sharing the principles and practices of a world-class education within a wide range of educational contexts.

Essential mindsets

As part of research and collaborations with K-12 schools and university partners around the world, we have developed the Global Mindset Framework, which identifies five mindsets that have emerged as most relevant to the future success of today’s students. Each mindset includes four key skills that demonstrate the actions that can be seen when cultivating the mindset. But just having access to a framework doesn’t mean it’s automatically linked to classroom practices — and some of these mindsets haven’t been typically taught in schools. As a result, we always consider how we can help educators to analyze, apply, and adjust learning frameworks as they incorporate them into their everyday teaching practices.

Putting the framework into practice

The challenge with any educational framework is translating it into meaningful practice for the teachers and students it's intended to serve. We were privileged to partner with the Brunswick School to integrate 21st century practices into a wide range of courses across all grade levels. We customized our professional learning approach to maximize the time we had together so teachers could have meaningful conversations, practical applications, and space to reflect on their experiences for deeper learning. We used a blended approach to professional development that included customized, professional learning videos and synchronous 75-minute sessions to explore the meanings of each component and practical application for classroom practices.

Metacognitive reflection

As we worked across department teams, we wanted to model the mindsets of the framework, so with each new mindset that we studied, we created a customized video with the basic facts, and then planned for an interactive face-to-face session where teachers developed practical strategies after watching the video and discussed the impact of the framework on their classes. Some teachers noticed that incorporating a new mindset each month allowed them to expand their learning outcomes beyond simply “critical thinking skills” and that they were setting critical goals for collaboration through group work and discussion, as well as creativity where they used imaginative writing prompts to help students expand their thinking. This kind of integrated thinking helped the teachers test and tweak their learning strategies immediately. By creating heterogeneous groups in these sessions, we were also able to support cross-grade professional learning conversations that generated great ideas from different vantage points. Teachers from the upper grades were amazed at the different planning and pedagogical moves made by the teachers in the lower grades. Similarly, the teachers in the lower grades benefited from learning more about student expectations in the upper grades. These realizations created space for metacognitive reflection about their practice, and challenged some of the assumptions we all have when thinking about planning for our specific grade/content area. Like working with students, we know that placing adults in strategic and flexible groupings is a powerful lever for keeping learning fresh. During the culminating session about their learning, each teacher was given an opportunity to share a lesson, unit, or project they implemented or planned to implement by applying a single or multiple mindset from the framework. Their learning was evident through their sharing and evidenced in the artifacts from their student work. In one case, a teacher hoped to have students investigate COVID-19 using actual numbers and data to unpack the pandemic. After interpreting the data, they would design charts and graphs to share their findings, make predictions for the long-term impacts of COVID-19, and offer recommendations for next steps. Throughout the project, students would implicitly be asked to demonstrate the Global mindset from our framework, as they strove to solve real-world problems.

Lessons learned

When educators consider the implications of the Global Mindset Framework within their own curriculum, we’ve seen how they cultivate their own mindsets, in addition to making direct connections to new teaching practices. Our partners demonstrated that when we scratch the surface of 21st century skills, we see that there are not only many innovative practices, but many unanswered questions. Some of our big learning moments and new questions included the following:

In education, we often encounter frameworks — whether it’s a framework for literacy, a framework for evaluation, or a framework for instruction — that should translate into practice. This translation can be achieved through thoughtful and intentional professional development that respects the knowledge of teachers and honors the ways adults learn. By structuring these professional learning sessions in both synchronous and asynchronous engagements, and using cross-content and grade-level groupings, teachers were able to interpret this essential framework in meaningful ways.

Wondering what this work could look like in your community? Reach out to us to discuss how you can bring essential 21st century skills to your students and community. 6/6/2022 Creating Transformational Change: Structures for Designing a Professional Development Series

A suggested sequence of sessions that encourages learning, application, reflection, and the sharing of promising practices.

Effective professional development can be defined as structured professional learning that results in changes in teacher practice and improvements in student learning. Features such as strong content focus, inquiry-oriented learning approaches, collaborative participation, and coherence with school curricula and policies can be the difference between good and great professional learning experiences.

Since the 1970s, there has been a growing body of literature about learning and the application of reflective practice, which is a way of allowing educators to step back from their professional experience, develop critical thinking skills, and improve future performance. When educators can learn a new idea or concept, apply this learning to their specific context/content area, reflect on the experience and share their experiences with colleagues — a cycle we call LARS — they can bring their professional learning experience to fruition.

Using the LARS model

The LARS model is a structure for developing ongoing professional development sessions that prioritize developing community knowledge, shared practices, and deepening reflection on what works, and why. In the planning process, facilitators should conduct a needs assessment to determine the strengths and struggles across the community and strategize an area of focus. For example, one school recently discovered student performance in reading was struggling. After conducting a series of Learning Walks, the school leadership team noticed that literacy instruction was inconsistent across classrooms. The leadership debriefed their experiences and came to the conclusion that if teachers were using similar instructional strategies for Before, During and After reading, students would have increased their comprehension and confidence. The leadership team reviewed several research-based strategies and identified two strategies for each stage of the reading process, for a total of six literacy strategies to share with the whole school. They began to use the LARS framework to structure a 12-week PD series. They knew that they needed two weeks per topic: one session to introduce the strategy and make a plan to implement it, and a second session to reflect on their implementation and make adjustments.

Learning