|

Turn the obstacles created by shifting learning styles into opportunities for adaptation and innovation.

When it comes to education, every era has its defining tools and methods, each playing a central role. From the iconic chalkboards that once graced classroom walls to the overhead projectors that illuminated our lessons, these tools were fundamental in shaping our educational approaches. However, as technology continues to progress, these traditional tools are gradually being replaced by more advanced alternatives.

As such, education must evolve to keep pace with these changes, and teachers need to adapt to new technologies and teaching methods to effectively meet the needs of their modern learners. In a world defined by 21st century innovation, we can no longer rely on 20th century teaching methods. Yet, embracing change is no easy feat! In a whirlwind of shifts, resistance often arises, especially from educators who’ve experienced firsthand the loss and excitement of these transitions. Many educators find themselves grappling with the need to let go of cherished beliefs and teaching methods rooted in their own experiences and identities. In my recent conversations with teachers, a common sentiment emerges: the perceived disinterest of students in reading, their struggle with mastering basic skills like multiplication tables, and their apparent lack of engagement in critical thinking. These concerns are undoubtedly valid. However, as educators, we must confront the reality that today's students interact with reading, interests, and motivations in ways vastly different from previous generations. Accepting these changes can be difficult, especially when they seem to highlight deficiencies. But if we examine the changes and evolutions of trusted teaching methods of the past, we can gain insight into how technology continues to shape our ways of living and learning, setting the stage for understanding which teaching methods have become obsolete in today's digital age. The textbook

Modern textbooks became a staple starting in the 15th century. These trusty learning companions were used by teachers and students for generations and were praised for their wealth of knowledge evident in their heavy weight. Carrying a textbook was once a symbol of academic dedication, but in today's digital world, textbooks alone do not suffice. They're too basic for modern learners who want interactive, multimedia experiences, and as technology advances and access to information increases, textbooks just can't keep up with the engaging and personalized learning experiences students need.

The encyclopedia

In the 16th century, the encyclopedia was introduced. It was once praised as the most powerful source of human knowledge, jammed between two hardbound covers. I remember being fascinated by Encyclopædia Britannica and waiting in line to use the limited supply in our classroom. I would turn the delicate pages to find answers to all sorts of questions. But today, hard copy encyclopedias are obsolete. Students now have access to the vastness of the internet for instant information and real-time updates.

Library catalog systems

In the 19th century, we experienced the creation of the modern library catalog system, with its neatly indexed cards and Dewey Decimal classifications. It was once the key to the world of knowledge within a library's walls — it guided students through the maze of shelves, leading them to the books and resources they wanted to read. I distinctly recall my visits to the library, armed with my own shiny library card, seeking advice and assistance from the librarian, and paying fees when I missed the return deadline.

Yet, with the advent of digital databases and online search engines, the catalog system is a symbol of the past, replaced by instant access to a wealth of information at our fingertips. Furthermore, the act of reading itself has undergone a significant transformation. While some still cherish the smell and feel of a physical book, like me, checking out physical books has become a distant memory for many. Many people have embraced the convenience of accessing articles, podcasts, audiobooks, and other digital formats. The act of "reading" has expanded to include a wide array of mediums, reflecting the changing preferences and lifestyles of readers and learners in the digital age. The only constant is change

These transformations reflect the resilience of education in the face of technological advancements, underscoring that with change comes the potential for growth, adaptation, and progress. Librarians have evolved into “digital resource coordinators,” “media specialists,” and “information specialists,” guiding learners through the digital landscape. And traditional book companies have transitioned to online platforms for greater accessibility and customization.

Today, we're facing rapid technological changes, like YouTube, TikTok, and social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. There's also a growing presence of Generative AI, which, like changes in the past, can feel daunting. These advancements are reshaping the learning landscape, with some fearful of the implications for originality and personal privacy, while others view them as an opportunity to revolutionize education by offering personalized learning experiences for every student. The importance of reflection for innovation

I've been encouraging teachers to ask: What are the goals I have for my students? Where do these goals originate, and do they align with the demands of the 21st century? These inquiries prompt us to determine when adjustments are necessary, whether it involves letting go of outdated methods, revising our approaches, or affirming current practices.

Recently, I've observed educators designing innovative and relevant projects that deeply engage their students. These projects often culminate in products inspired by social media or TikTok videos, and sometimes incorporate QR codes for added interaction. For example, in a history class, students were creating short TikTok-inspired videos depicting key historical events or figures, using creative props and costumes to make the content engaging and memorable. These challenges can encourage active learning and collaboration among students, as they work together to brainstorm ideas and produce their videos. In a science class, I witnessed students engaging in a "Science Experiment Challenge" where they were tasked with filming themselves, with help from the technology teachers, conducting simple experiments and explaining the scientific principles behind them. This not only reinforces learning but also allows students to showcase their understanding in a fun and interactive way. In an art class, a teacher had her students showcase their creative projects by creating a series of Instagram- inspired posts including captions and comments, allowing them to document their artistic process from conception to completion. And in an ELA class, a teacher shared how she has been using AI platforms, like Brainly, to provide additional support to her students by offering personalized tutoring sessions, answering questions, and providing explanations on various topics, supplementing traditional classroom instruction. These examples demonstrate teachers’ efforts to stay updated on technological changes and connect with students by leveraging their interests.

Regardless of your sentiments around these shifts and changes, their impact on students cannot be denied. Therefore, it's crucial to shift our focus towards supporting students in developing the skills and competencies necessary for success in the modern world. Rather than viewing students' changing learning styles and interests as obstacles, we must see them as opportunities for growth, adaptation, and innovation.

By meeting students where they are and embracing their unique perspectives, we can foster a learning environment that encourages curiosity, critical thinking, and engagement with the world around them. This approach not only prepares students for the challenges of today, but also equips them with the resilience and adaptability needed to thrive in an ever-changing future.

References

The Journal of American History Textbooks Today and Tomorrow: A Conversation about History, Pedagogy, and Economics Encyclopedia Britannica

Engage students in rich mathematical tasks that honor the process more than the solution.

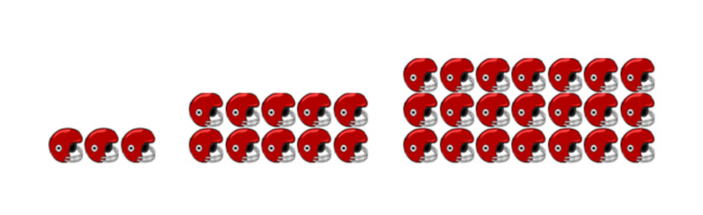

I was recently sitting with a high school algebra teacher — who was preparing a lesson about translating sequences into functions or equations — and trying to encourage him to use this archive of visual patterns with his students. We discussed matching different groups of students to different images and asking them to try writing an equation for the pattern. As the teacher started practicing on his own, writing equations for some of the patterns that were offered, this picture came up, and we both began to struggle.

Neither of us could figure it out.

Other teachers started coming by to join: “There has to be an exponent in there somewhere...” “But just an exponent wouldn’t make sense…” “Are we multiplying the exponent? Or maybe multiplying and adding?” This had started with only one teacher, but soon there were five teachers huddled around this image, trying to find a solution. One teacher got out a marker and began writing possibilities on the board. Another started running through calculations in their head, shouting out theories. Finally, one teacher said, “Oh, it’s a quadratic!” The algebra teacher who had started with me stated, “see I can’t do this with my students, we couldn’t even figure it out”. But I had the complete opposite reaction. I was surprised at how many had engaged in our puzzle. We were all trying out different methods, debating and discussing throughout our process. This is what a math classroom should look like every day.

Making room for authentic engagement

As math teachers, it can feel scary to introduce a problem to students that doesn’t have a clear and simple solution. But how else is authentic math engagement supposed to happen in the classroom? In our example, even if we had never arrived at a solution, all the math thinking and practice we did to try and get there would have been worth the struggle. Even if a student never achieved a correct equation or solution, they still would have stretched their thinking and understanding of patterns and functions just by trying to work through the task. The inspiration for this task came from Jo Boaler’s work on Mathematical Mindsets. In her book, she reminds us how beautiful and rich mathematical thinking can be, and offers advice on how to bring that into your classroom. This task we were testing out among teachers includes many of the suggestions she offers for making rich mathematical tasks. Boaler describes these tasks as having multiple entry points, visual components, and options for inquiry and debate. As you incorporate these elements into the math tasks in your classroom, consider the following questions as you shift into a richer mathematical lens:

Our original task starts with a visual component and includes multiple methods of entry. Students have the opportunity to make sense of the visual in any way they see fit — maybe they prefer to focus on the numbers, or maybe they want to look at the way the shape of the image is changing. There are no clear steps to follow to solve this puzzle; students have to play and engage in multiple ways before they can predict patterns and solutions. Another great aspect of this task is that students of all math levels can participate and still walk away learning something from the experience. Maybe some students will leave noticing there is not a constant amount of change between the pictures. Maybe some students will consider the way addition and multiplication look different in patterns. Maybe some students will write a quadratic equation and then be able to predict future images. The possibilities are endless.

When we provide math problems that have very clear and explicit steps, we may lead students to the correct answer, but we also limit the creativity they can experience. We teach students that there is a right and wrong way to do math. We contribute to the negative feelings and attitudes many students already have about math. And lastly, we take away the fun.

Making room for rich mathematical tasks that have multiple entry points, opportunities for debate, and visual components can help make every student feel like they can one day be a real mathematician. It can help students of all levels rediscover the fun in math.

Break away from the "I did all the work, and they did nothing" refrain.

As a student, I dreaded hearing the words, “This is going to be a group project.” In my mind, this translated to, “You are going to have to do all of the work for this project and let 2-3 other people take credit for it under the guise of collaboration.” I liked to talk to my classmates and work together on low-stakes assignments, but I cringed at the prospect of long-term group projects that would be graded as an assessment.

As a new teacher, I quickly lost sight of my own experiences as a student. In the spirit of collaboration and teamwork, I often assigned group projects in my classroom, until, one day, a student said, “Oh great, that means I will have to do all the work again.” This comment catalyzed a turning point in my teaching: I realized that I couldn’t keep assigning group work in the same way that I had been assigned group work in school. I needed new norms and strategies for group work — ones that created accountability and equity.

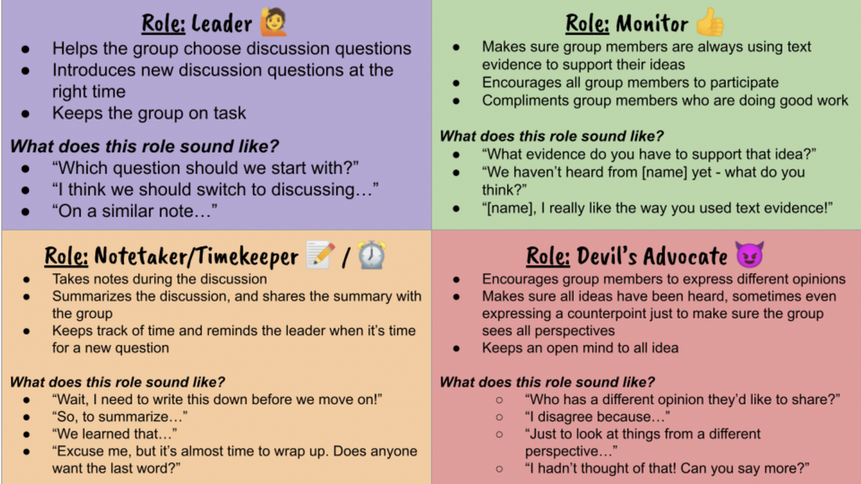

Assigning & assessing group work

Clearly define the group's task and objectives. Make sure that each group member understands their role and the expectations for their work. This stage of the group work process should have an adult involved to make sure that each group member has an equivalently rigorous task to complete. Assign specific roles to each group member. This can help ensure that everyone is contributing to the group's work, and can also serve as a way to evaluate individual performance. Perhaps one student will take the lead on communicating with the group and setting up meeting times, whereas another student will take the lead on identifying next steps to complete the project. Here are some student roles to consider:

Created by by Alanna Tuller, ELA teacher in New York City, informed by source

Set clear criteria for evaluating the group's work and each individual's contribution. This can include factors such as attendance and participation, quality of work, adherence to deadlines. These criteria can be tied to students’ roles listed above.

Provide regular teacher feedback to the group and to each individual member. This can help ensure that everyone is aware of their strengths and areas for improvement, and can also serve as a way to track progress over time. Use a combination of formative and summative assessments. Formative assessments can help identify areas where the group needs to improve, while summative assessments can be used to evaluate the final product or performance. Use various forms of assessment to evaluate student performance, like self-evaluation, peer evaluation, and teacher evaluation. This will provide a comprehensive view of the student's performance. I like to give students in a group an anonymous survey to communicate with me about strengths and areas of growth for their group. By giving this survey at a few points over the course of the project, I was able to intervene when groups needed a teacher mediator involved to get back on track.

Group work has its challenges, and many students come to our classrooms with negative past experiences of collaborative learning. As educators, we can transform what group work looks like in our classroom spaces by establishing clear expectations and holding students accountable to one another and to the learning process. If we implement these norms, perhaps students will respond to the prospect of group work with, “Great! I’m excited that we get to work together as a team.”

Strengthen the connection between the why and how of student learning, cultivating essential 21st century skills along the way.

In a recent conversation with leadership at a school district in Westchester, NY, I posed the question: What do we recognize as the purpose of education, and what is it we want and hope for our students when they graduate? My intention in asking this was to encourage leadership to explore whether the goals and values they have for their students are reflected in their current efforts, including their curriculum, instruction, and initiatives. Put frankly, I was asking leadership for their thoughts around what they were doing, and if they thought it was best preparing students for the 21st century.

After some lengthy discussion and a deep dive into their curricular maps, it was revealed they had work to do. Despite their good intentions, they were still operating from old-fashioned and insufficient pedagogies. Unfortunately, through our research and experiences, we’ve found this is the case with most schools today. A look back through history can help underscore this point.

Education for what?

In the 19th century, the purpose of education and schooling was to prepare students for work. There was one schoolhouse, and one teacher for many students, all of whom sat in rows. Instruction was focused on repeating, reciting, and reproducing — all skills necessary for work, which was predominantly in factories. In the 20th century, things evolved, thanks to the introduction of basic technology like the typewriter. Schooling focused on teaching students to apply information provided by a teacher or by a resource, like textbooks. Like the 19th century, there was a strong connection between school and work, though the necessary skills shifted to accommodate work in an office, and revolved around application and analysis. Now, about a quarter into the 21st century, we are faced with a problem we’ve yet to experience. It’s the first time in history we are presented with a disconnect between what and how we are teaching, and the realities of a 21st century world, where technology continues to change and shape our experiences. Organizations today are seeking innovative and imaginative individuals, yet students are still looking to the teacher to provide the answers, and there is little to no opportunity for students to engage in critical and creative thinking, or individual and collaborative problem-solving. Our needs and goals as a society are evolving but sadly, most of our schooling is not. As my colleague Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang says: We can’t use a 20th century pedagogy in a 21st century world. How can we adapt to 21st century work and support students in acquiring skills that we know will serve them in the 21st century and beyond?

The promise of project-based learning

One of the most powerful ways to advance the skills and capacities necessary for students to thrive in today’s society is through project-based learning (PBL). PBL supports the development of fundamental skills such as reading and writing, as well as 21st century skills like research, collaboration and communication, problem-solving, time management, and the use of technology. In short, PBL sparks curiosity and curiosity leads to innovation. What is PBL? As the Buck Institute states, project-based learning is “A teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by working together for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an authentic, engaging, and complex question, problem or challenge.” They also offer a distinction between “dessert” projects and “main course” projects that is particularly helpful — a dessert project is “a short, intellectually-light project served up after the teacher covers the content of a unit in the usual way” whereby a “main course project is when the project is the unit.” When it comes to CPET’s approach to project-based learning, we very much lean on the expertise of the Buck Institute. We believe projects:

Imagining project possibilities

How might teachers and students begin this work? Start with a real-world problem far away Projects that are focused on a global issue help students demonstrate understanding of a problem that occurs in the world, even if it isn’t directly about them. Students can explore the features of this problem, how it impacts the people, as well as the far-reaching implications and solutions!

Start with a real-world problem close to home This type of project can help students demonstrate understanding of a problem that occurs in their specific context. Identifying a problem locally engages people intimately and can inspire calls to action that are more likely to be carried out. The goals would be to understand a situation, issue, or a series of events that happen in multiple contexts around the world and ideally consider the global connections across diverse communities.

Meditate on a word, concept or theme Words are powerful, and making use of “academic” vocabulary or transferring knowledge from one domain to another are two areas where schools struggle to build students’ capacity. A project on a general word, concept, or theme is engaging and develops these important skills across content areas.

Our students have the potential to do amazing things. They just need the right conditions to survive and thrive. Project-based learning promotes the acquisition of real and relevant skills of the 21st century by asking questions, exploring issues that matter, and imagining possibilities for positive change. PBL is now the focus of my work with the district in Westchester, and I’m really excited by the progress they’ve made. I invite you to use any of these practices to support the creation of your own project, and if you need more help, we are here!

Build a classroom culture that encourages active listening and a willingness to consider others' perspectives.

When I was a middle school English Language Arts teacher, I often asked my students to engage in debates inspired by our readings. For example, I once asked my students to read Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” — a short story in which a group of villagers participate in a long-standing tradition of stoning to death the “winner” of a mandatory lottery — and to debate whether or not the villagers could be considered “murderers.”

The prompt for students to “debate” with one another had its benefits: my students often became passionate to defend their beliefs and their analyses of the text, and students read the text closely to identify evidence and to justify their thinking out loud. However, notable shortcomings also arose when students engaged in the task of debate: they often became combative and indignant when others did not agree with them, and they seemed resistant to change their initial side of the argument. At any age, it can be challenging for students to admit that they have changed their minds, especially in front of their peers. Even moreso, it can be challenging for students to actively listen and to respond to others’ points of view and analyses. It requires the ability to welcome or to accept a new idea or perspective. An excellent way to foster this kind of openness in the classroom — this culture of intellectual and social empathy — is to ask students to participate in what Peter Elbow called “The Believing Game.”

Balancing believing & doubting

The task of debate often asks students to participate in what Elbow called “The Doubting Game.” The doubting game requires students to be skeptical and as analytic as possible. It encourages students to try hard to doubt ideas, to discover contradictions or weaknesses, and to scrutinize and test others’ logical reasoning. This kind of critical thinking can be incredibly valuable, but it can also foster a classroom culture that only celebrates doubting, whether that be doubting ideas presented in a text or ideas presented by others in the classroom space. Contrastingly, “The Believing Game” asks students to try to be as welcoming or accepting as possible to every idea they encounter: not only to listen to different views, but also to hold back from arguing with those different views. Further, the believing game asks students to restate others’ beliefs or arguments without bias and to participate in the act of actually trying to believe them. Elbow points out that “often we cannot see what’s good in someone else’s idea (or in our own!) till we work at believing it…when an idea goes against current assumptions and beliefs — or if it seems alien, dangerous, or poorly formulated — we often cannot see any merit in it.”. Including the believing game in your classroom does not need to coincide with the removal of the doubting game. The act of doubting — of critically thinking to develop thoughtful skepticism — is an undoubtedly important skill for students to develop in order to discern truth. But, a sole focus on doubting, as I shared from my own teaching experience, can lead to a classroom culture in which students are always inclined to doubt. This inclination can lead to rigid thinking, and an unwillingness to listen, respond, and grow. At its worst, this inclination can lead to a classroom culture in which students become hostile towards other students’ beliefs or ideas that seem oppositional to their own.

The benefits of believing

Peter Elbow, the creator of the believing and doubting games, is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He has written extensively about the benefits of methodological believing for students and teachers. He identified three main benefits for the believing game in classrooms:

Engage students in the game of believing

The opportunities for students to participate in the game of believing are endless. I offer here a few suggestions for simple ways to engage students in the game of the believing.

6/7/2022 Lessons from the Field: Practice and Professional Learning with the Global Mindset Framework

Making a 21st century skills framework meaningful for K-12 instruction.

Over the past century, advanced technology has made the world smaller and smaller. This has perhaps never been truer than the past decade, in which social media has made it possible for a tweet or an Instagram post to be seen around the world in mere seconds. Consequently, we see and have many more collective experiences. This was perhaps never more evident than over the past few years with the shared experience of a global pandemic and a rapid impact on learning in most parts of the world.

As we were thrust into new ways of thinking about teaching and learning, different mindsets, and different ways of imagining schools, we were faced with the truth that we can no longer sustain a 20th century in a 21st century world. The task before us is to educate students today for the world they’re poised to lead tomorrow. As a founding organization of the Global Learning Alliance (GLA), we have been thinking about reimagining education and preparing educators for the future for quite some time. The GLA is the outgrowth of our groundbreaking research in five of the top PISA-ranked cities around the world on the features and practices surrounding 21st century teaching and learning, and is committed to cross-cultural research collaborations as an effort to define a pedagogy that takes into account the dynamic needs of our changing world. Through this work, we are dedicated to understanding, defining, applying, and sharing the principles and practices of a world-class education within a wide range of educational contexts.

Essential mindsets

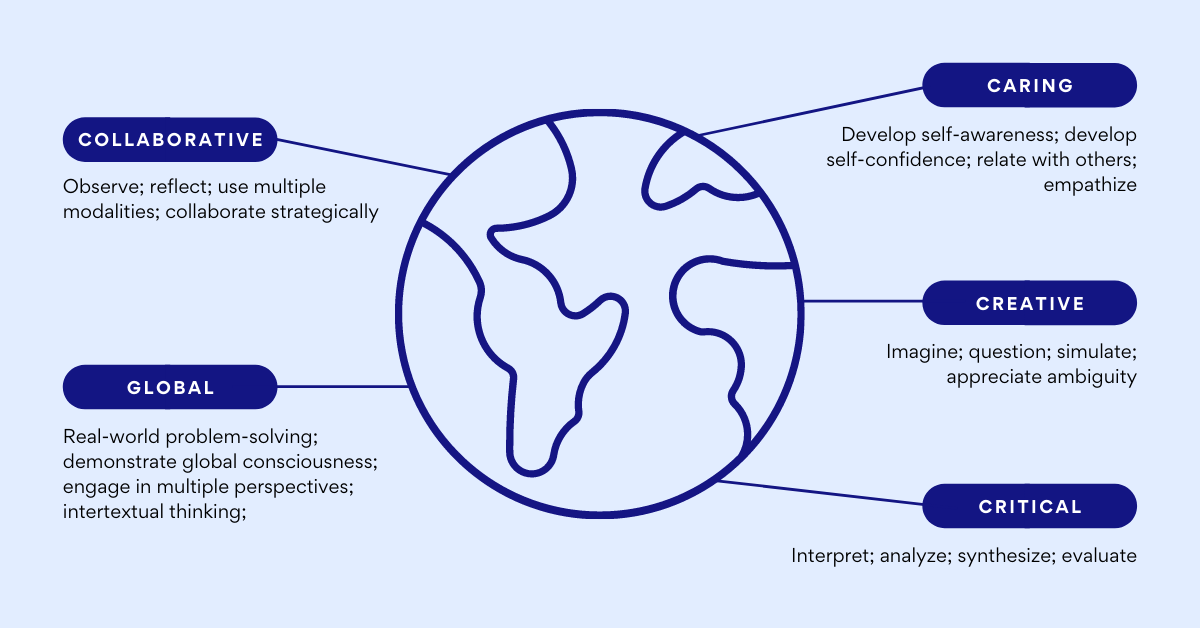

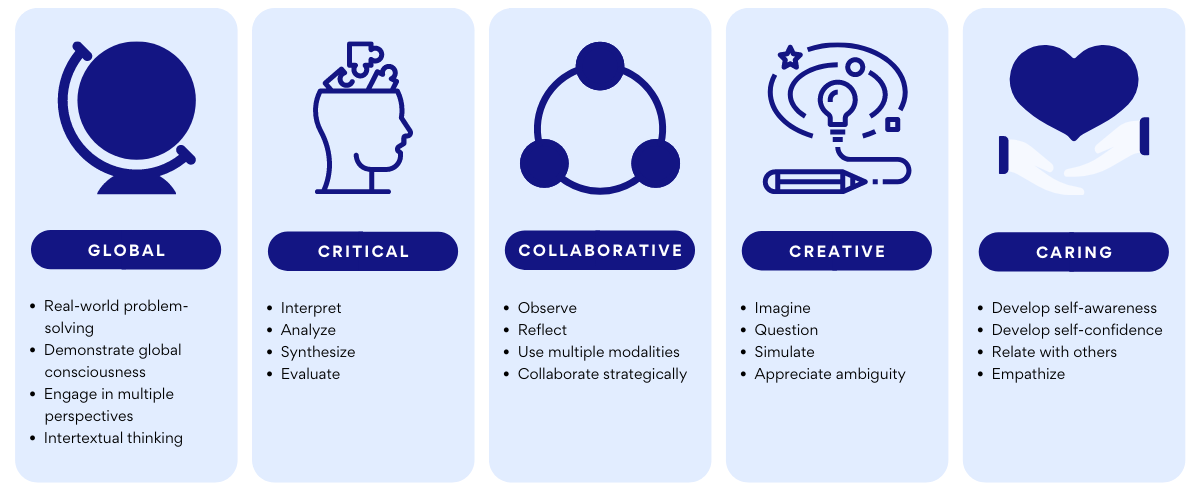

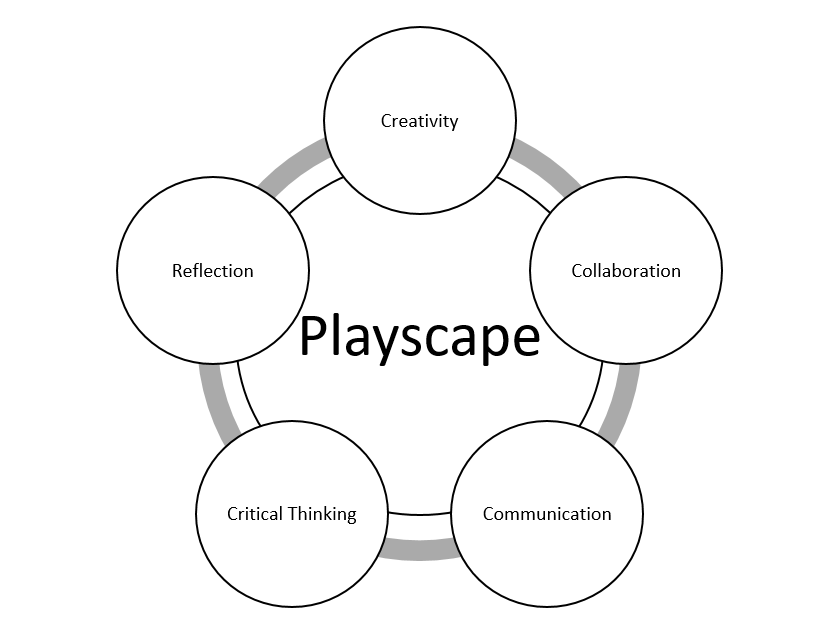

As part of research and collaborations with K-12 schools and university partners around the world, we have developed the Global Mindset Framework, which identifies five mindsets that have emerged as most relevant to the future success of today’s students. Each mindset includes four key skills that demonstrate the actions that can be seen when cultivating the mindset. But just having access to a framework doesn’t mean it’s automatically linked to classroom practices — and some of these mindsets haven’t been typically taught in schools. As a result, we always consider how we can help educators to analyze, apply, and adjust learning frameworks as they incorporate them into their everyday teaching practices.

Putting the framework into practice

The challenge with any educational framework is translating it into meaningful practice for the teachers and students it's intended to serve. We were privileged to partner with the Brunswick School to integrate 21st century practices into a wide range of courses across all grade levels. We customized our professional learning approach to maximize the time we had together so teachers could have meaningful conversations, practical applications, and space to reflect on their experiences for deeper learning. We used a blended approach to professional development that included customized, professional learning videos and synchronous 75-minute sessions to explore the meanings of each component and practical application for classroom practices.

Metacognitive reflection

As we worked across department teams, we wanted to model the mindsets of the framework, so with each new mindset that we studied, we created a customized video with the basic facts, and then planned for an interactive face-to-face session where teachers developed practical strategies after watching the video and discussed the impact of the framework on their classes. Some teachers noticed that incorporating a new mindset each month allowed them to expand their learning outcomes beyond simply “critical thinking skills” and that they were setting critical goals for collaboration through group work and discussion, as well as creativity where they used imaginative writing prompts to help students expand their thinking. This kind of integrated thinking helped the teachers test and tweak their learning strategies immediately. By creating heterogeneous groups in these sessions, we were also able to support cross-grade professional learning conversations that generated great ideas from different vantage points. Teachers from the upper grades were amazed at the different planning and pedagogical moves made by the teachers in the lower grades. Similarly, the teachers in the lower grades benefited from learning more about student expectations in the upper grades. These realizations created space for metacognitive reflection about their practice, and challenged some of the assumptions we all have when thinking about planning for our specific grade/content area. Like working with students, we know that placing adults in strategic and flexible groupings is a powerful lever for keeping learning fresh. During the culminating session about their learning, each teacher was given an opportunity to share a lesson, unit, or project they implemented or planned to implement by applying a single or multiple mindset from the framework. Their learning was evident through their sharing and evidenced in the artifacts from their student work. In one case, a teacher hoped to have students investigate COVID-19 using actual numbers and data to unpack the pandemic. After interpreting the data, they would design charts and graphs to share their findings, make predictions for the long-term impacts of COVID-19, and offer recommendations for next steps. Throughout the project, students would implicitly be asked to demonstrate the Global mindset from our framework, as they strove to solve real-world problems.

Lessons learned

When educators consider the implications of the Global Mindset Framework within their own curriculum, we’ve seen how they cultivate their own mindsets, in addition to making direct connections to new teaching practices. Our partners demonstrated that when we scratch the surface of 21st century skills, we see that there are not only many innovative practices, but many unanswered questions. Some of our big learning moments and new questions included the following:

In education, we often encounter frameworks — whether it’s a framework for literacy, a framework for evaluation, or a framework for instruction — that should translate into practice. This translation can be achieved through thoughtful and intentional professional development that respects the knowledge of teachers and honors the ways adults learn. By structuring these professional learning sessions in both synchronous and asynchronous engagements, and using cross-content and grade-level groupings, teachers were able to interpret this essential framework in meaningful ways.

Wondering what this work could look like in your community? Reach out to us to discuss how you can bring essential 21st century skills to your students and community.

In order to succeed, students need to practice connecting and empathizing with others.

As I sit here at my computer, I could also be video chatting with a relative in Argentina while checking airfare prices, ordering pizza to be delivered in an hour, checking the weather for next weekend, finding an inspirational quote to add to my workshop tomorrow, and checking who the seven dwarves are because it’s been bugging me. And the funny part is, none of this would seem unusual to you! With a smartphone or computer and a good wifi connection, knowledge and information is a click away. Watching my own children attend school from home this past year gave me insight into how much technology is affecting schoolwork. Yes, they are still doing math, still reading, still writing, but there is also this: “Alexa, how do you spell “suggestion?” “Alexa, which fraction is larger- ⅔ or ¾?” Yikes!

When we think about the future, we tend to imagine the remarkable technology that will continue to develop. And so, when thinking about what skills our students need to thrive in the 21st century, the gut response is more tech skills, more computer savviness. But acquiring more tech skills can only get us so far. What students need is the ability to think critically, and the ability to collaborate with diverse thinkers. To do this, our students need to be taught how to connect and empathize with others.

Teaching empathy

When I think about students who have really stood out to me, from middle school to graduate school, I think of the students who could work with anyone — the ones that helped their classmates shine bright. Those are the students I remember the most. I’d like to make a case that it is possible to teach this, or put structures in place to teach students to think outside of themselves. To teach students the importance of getting along with others, and seeing the world from another point of view. In a recent speech by President Joe Biden, he urges Americans to practice empathy for the health of our country. He reasoned: “For empathy is the fuel of democracy. Let me say that again: Empathy — empathy is the fuel of democracy, a willingness to see each other — not as enemies, neighbors. Even when we disagree, to understand what the other is going through.” That ability to see “what the other is going through” is something we can teach. And as President Biden points out, this quality that may have once been thought of as a soft skill is one that we need to fuel our democracy. One way to “understand what the other is going through” is through reading. While I am not an immigrant, I can dive into the lives of Jhumpa Lahiri’s characters in The Namesake and experience Ashima’s deep loneliness in Cambridge, longing for her family, feeling like a foreigner. I can also experience her delight when she realizes she can recreate her favorite street snack from Calcutta — a mixture of peanuts, Rice Krispies, onions, and spices. As a teacher reading The Namesake in an English or Humanities class, I would invite students to sit with Ashima for a while. Live in her loneliness a bit, stew in the feeling of everything feeling unfamiliar. Offer students a choice for how they can engage with the characters, such as:

There are so many ways to empathize with characters in English or Humanities classes, through reading, writing, and discussions.

Connecting to content areas

In an interview with Life Magazine, James Baldwin explains, “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.” Baldwin reminds us all what it means to be human, and through literature we can feel each other’s pain, knowing we, too, have experienced the same. While the particulars may be different, we all have hard moments of hardship that have “tormented” us in some way. But how do we explore this in subject areas other than English or Humanities? Or for students who may not be able to empathize in such a way? For content area classes, Facing History offers a tool to help students forge a connection with something they have read or are exploring.

Using this tool invites students to spend time thinking, probing, and considering how an event or problem is relatable in some way. Facing History suggests using these prompts with the chart above (available for download here):

Students can easily use this tool in History or Science, as they are learning about scientific discoveries or ethical dilemmas involved in scientific explorations. If we want to help our students become 21st century thinkers, we have to create scenarios in which they are stepping outside of themselves, extending into another’s world in some way. This is what will help students build ideas together. This is what will make our students think more complexly.

Our equations can always be situated in the real world, which offers our young people another perspective. Another way to teach empathy in all subject areas is to normalize students helping each other, teaching one another, and working together to solve problems. Teaching students how to teach their classmates signals to them that you value collaboration, and that the ability to teach and work together are significant, valued characteristics. Encouraging students to step into a teaching role will also help them gain a greater awareness of the topic at hand — when students take on the qualities of a teacher, they are not only learning how to work with their classmates, but simultaneously becoming more of an expert on the subject.

Technology will continue to develop at a rapid pace, and knowledge will continue to be accessible to all of us. Creating situations where students learn to step outside of themselves is what will propel our students into more complex and critical ways of thinking. We must continue to focus on how we can help our students think about each other and our world, and encourage them to collaborate and share ideas. As President Biden put it, this is what fuels our democracy. This is how we will stay 21st century ready.

Encourage curiosity and caring in young learners, and support an understanding and appreciation of differences.

Conversations about race are not easy. They can bring about feelings of fear, anger, and frustration, and as a result, these conversations are often avoided. However, grappling with topics of race and diversity are truly important, especially with young children who are cultivating their understanding and their perceptions of the world. Experts argue that children are never too young to learn about kindness, fairness, and human rights. Research states that children “as young as three months old...may look differently at people who look like or don’t look like their primary caregivers.”

As a parent of a soon to be two-year-old and a professional development consultant who works closely with educators of young children, I am committed to seeking ways to engage in and facilitate my own conversations about race, especially in today’s world, as well as share strategies with educators that they can use in their own classrooms. What follows are a few strategies I’ve curated and adapted from my own musings and readings, as well as some concrete strategies inspired by one of our reimagining education initiatives: Literacy Unbound. These strategies can be particularly helpful when it comes to facilitating conversations about race with young students and cultivating skills, mindsets, and capacities that will serve us well today, and in the future.

The importance of asking questions

One of the most effective ways to grapple with topics of race and diversity is to ask questions. This is particularly effective with elementary students, as they commonly ask many questions of their own. By encouraging their curiosity and caring, and creating a safe space for them to be inquisitive, you can help pacify concerns, address confusions, and support an understanding and appreciation of differences. Additionally, you can raise your own questions focused on topics of race, diversity, and exploring differences to get students thinking and recognizing how they can be advocates of positive change. Here are some examples of questions that I turn to, curated and adapted from websites like PBS.com:

These questions can be a part of morning circle time, a weekly reflection or journal writing prompt, or even as a theme for a bulletin board, where students can share their responses using post-its or index cards (or, while online, students can add their thoughts online to Padlets and Jamboards).

Introducing & exposing students to diverse books

As Dr. Aisha White, Director of the P.R.I.D.E. Program at the University of Pittsburgh, explains, books — especially picture books — are a safe place to start when talking to children about race and racism. She suggests selecting picture books that offer multiple perspectives and explore various entry points for addressing complex topics. Some popular texts she suggests include:

These texts can be read as part of designated read aloud time, as part of a school-wide, character building initiative where the books are read in every classroom, or as a central text that guides and inspires a larger unit of study. But as Dr. White explains, it’s not enough to just read the book. “If a parent (or educator) just reads the book and doesn’t have a conversation — doesn’t start to talk about racial disparities and racial discrimination and racism in America — then it won’t really affect a child’s attitudes toward race…it comes back to…having a background knowledge before speaking with their children, and being brave enough to have the tough conversations.” What does it look like to support students in reading complex texts more closely, more carefully, more creatively, and more critically?

Sparking conversations around texts

Literacy Unbound, one of our signature initiatives, aims to unbind traditional approaches to the teaching of reading and writing using drama and play-based strategies to spark conversations that are inspired by questions raised in a specific, shared text. Teachers and students are brought together in this process as critical and creative thinkers, which helps foster a space for collective inquiry and exploration. Using drama and play can be particularly effective with young students, especially when looking to support engagement and participation, while also providing a safe entry point for complex and challenging conversations. Let’s look at a few strategies from Literacy Unbound to see how they can be effective and what they can look like when applied to one of my favorite texts, The Other Side, by Jacqueline Woodson. The Other Side follows the story of a little Black girl named Clover who sees a little white girl across a fence, but is told by her mom that she can’t cross to the other side of the fence because it isn’t safe.

Facilitating conversations about race with young students is no easy task. It takes courage, patience, and a lot of thoughtful planning and reflection on the part of educators, parents, and caretakers. Moreover, it takes a lot of persistence. Being open-minded and developing understanding, kindness, and an appreciation of others who are different from us is not something that happens after reading one text or engaging in one conversation.

As Glenn Singleton and Curtis Linton note in their book Courageous Conversations About Race: A Field Guide for Achieving Equity in Schools, courageous conversations about race require that we stay engaged and anticipate feelings of discomfort, as well as expect and accept non-closure. We encourage you to create space for these conversations with your students and reimagine the ways in which you can spark curiosity and critical thinking around race and equity in a safe and supportive classroom.

Simple steps to support students as they assess the validity and intentions behind informational sources.

Once upon a time, being literate was as simple as being able to read, write, and do arithmetic. As educators, we also know literacy is a social construction, and being literate implies that an individual has the ability to interpret, produce, understand, and interrogate language appropriately. However, our understanding of what it means to be literate in the 21st century has been further complicated by the myriad of “literacies” we’ve come to recognize, including:

As the definition of literacy has broadened, so have the modes for finding and sharing information. This has increased exponentially with advances in technology, and is indicative of the natural shift in our understanding of 21st century literacy. The need to use multiple literacies to unpack information is tied to the need to interpret the many formats, sources, or media through which we obtain information. For educators, the challenge becomes more about how we need to teach students to interpret and assess information — not simply how to gain access to it.

The trouble with technology

Literacy development that includes technology can both support traditional literacies, and introduce new forms in the classroom. Technology can support each literacy type listed above by helping students gather a range of sources that will support them in discussing their ideas. Between smartphones, tablets, voice commands, and even Alexa, information is readily available everywhere. This is great, right? Yes, except that we are finding more and more examples of misinformation and disinformation in our daily diet. Recent articles in the New York Times and other educational sites such as Teaching Kids News further explore this topic, and emphasize the importance of understanding what it means to be literate within the context of this information-heavy era. Even if accessible information is every educator’s dream, we should not simply be giving fish to our students but rather, teaching them to fish — bolstering their literacy skills by helping them to make sense of the information around them by means other than traditional reading and writing. By teaching them how to assess the validity and intentions behind informational sources, we can empower them to raise concerns, and to verify unfamiliar or questionable sources.

Understanding misinformation & disinformation

According to Business Insider, the term misinformation refers to information that is false or inaccurate, and is often spread widely with others, regardless of an intent to deceive. Some of us may have done this ourselves and later realized that we misunderstood what we were sharing. Remember the game of telephone? One person would talk to the person next to them, and their words would travel from person to person around the room. At the end, we would often laugh at how distorted the original message had become from between the first person and the last. That is misinformation. Misinformation can turn into disinformation when it's shared by individuals or groups who know it's wrong, yet continue to intentionally spread it to cast doubt or stir divisiveness. Often, disinformation — or what some may call “fake news” — is generated to be deliberately deceptive. As educators become clearer about the distinction, it can be better communicated to students.

Emphasize how, not what to think

To combat misinformation and disinformation, it is essential that we teach our students to become critical thinkers. Learning critical thinking skills can also enhance academic performance by developing judgement, evaluation, and problem-solving abilities. This skill also transcends into practical aspects of daily life, and ultimately into college and career readiness. We can promote these skills by letting students know that we do not have all the answers, and instead offer them opportunities to unpack and understand information on their own.

With so much information at our fingertips each day, the importance of critical thinking skills cannot be overstated — it is imperative that we teach students how to interpret facts and assess the validity of informational sources. These skills will allow them to investigate the information they’re receiving, and identify misinformation in the process, helping them to become truly literate for the modern world.

Breathe new life into book clubs and place students at the center of their reading experience.

Time moves forward, as it always does. We can take this time to reflect on lessons learned when we unexpectedly and quickly shifted from teaching in the classroom, to teaching remotely, and then into a next normal of blended in-person and virtual learning spaces. One big takeaway from this time of critical reflection is that we aren’t starting with a blank page. Whatever the season, we can adapt tools we already have to meet the challenges we’re facing.

Breathing new life into book clubs

New tools can breathe new life into our planning and our teaching, and creating a new tool doesn’t need to be done from scratch. By connecting Ten Tips for Successful Book Clubs with our Global Mindset Framework, we can quickly create a new resource that integrates teaching 21st century skills into each reading opportunity we plan for our students. Book clubs offer many benefits to student readers, including:

A successful book club for your students will:

Understanding the Global Mindset Framework

Now that we’ve framed some of the characteristics of book clubs, we can connect each facet to our Global Mindset Framework. This will help us streamline our work when planning for our next book club iteration, or beginning a book club community with our students.

The Global Mindset Framework is the articulation of 21st century skills students need to navigate their present and their future, sorted into five categories of capacities: caring, collaborative, creative, critical, and global. The framework addresses key questions that teachers and school leaders struggle with as they attempt to make key concepts relevant to children in a changing world. To understand the Global Mindset Framework, we can look to the Global Learning Alliance (GLA). The GLA is the outgrowth of our groundbreaking research on the features and practices surrounding 21st century teaching and learning. It has evolved from the seeds of a research project and is now a consortium of schools and universities around the world dedicated to understanding, defining, applying, and sharing the principles and practices of a world-class education within a wide range of educational contexts.

21st century capacities

Global capacity: The capacity for students to step outside the confines of their own familiar social world to understand distant realities in order to engage productively with the world. Critical capacity: The capacity for students to develop their full critical cognitive capacities in order to be discerning and informed citizens of the world. Collaborative capacity: The capacity for students to develop habits of observation, reflection, and collaboration, and to be able to communicate in multiple modalities such as through images, words, sounds, gestures, or an integration of these modes in order to actively contribute to various discourses in the world. Creative capacity: The capacity for students to follow their curiosity by questioning or imagining in order to contribute positive improvements or inventions to their world. Caring capacity: The capacity for students to explore compassion, empathy, and self-awareness in order to develop caring partnerships with themselves, their communities, countries, and world.

Activating 21st century skills

Using the template below, we can imagine how we might combine various capacities from the Global Mindset Framework with our tips for success to generate a profile of a book club that integrates 21st century skills into student learning. We want to keep moving our teaching forward to meet the needs of today’s students, but we don’t often feel we have the time we need to recreate our plans. By layering the Global Mindset Framework over our book club planning, we can revise what we’ve already got going for us instead of starting from a blank page.

Connecting skills to next steps

Using the template above, we can customize our profile to fit a specific book — in this case, we'll use Malala Yousafzai's I Am Malala: How One Girl Stood Up for Education and Changed the World. In this model, we start with our to-do list; we imagine some of our options, and what we need to collect to complete our plan.

The task before us all is to educate students today for the world they’re poised to lead tomorrow, and as we recognize that we can no longer sustain a 20th century in a 21st century world, we must remain flexible in order to meet the dynamic needs of our students. As we look for ways to build upon the expertise and techniques already alive in our classrooms, we can easily create opportunities for students to build 21st century skills, shifting from teacher-centered instruction to an environment that puts students at the center of their reading and writing experiences.

Offer your students an opportunity to solve real world problems, demonstrate critical thinking skills, and collaborate with their peers.

Problems. There’s no shortage of them these days — the pandemic has spurred countless challenges and intense despair; there are too many to list. Teaching during the pandemic has been a challenge in and of itself, as we are always looking for ways for students to be engaged with curricula and drive their learning, and that’s hard to do whether we’re teaching in person or remotely.

If you think back to your college or grad school days, you may recall the constructivist thinkers, such as Jean Piaget, who believed that students learn best when they construct their own learning. Problem- and project-based learning offers teachers an opportunity to do just that — instead of telling students the answers, you can create a learning environment in which students learn through discovery, thinking, tinkering, reflecting, and developing answers on their own. We may already be familiar with ways that we can bring this type of learning to in-person classrooms, but it can also be delivered to students who are learning in remote or blended environments.

Problem-based learning vs. project-based learning

Project-based learning is situated in real-life learning. The Buck Institute for Education defines project-based learning as a “teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an authentic, engaging, and complex question, problem or challenge.” If you ever walk into a classroom and see students working on a project with an exciting buzz in the room, chances are, their teachers have designed a project-based learning task. In our own lives, we know that when working on a project, we often discover a problem we didn’t realize we had — but once it surfaces, it demands a solution. (Remember those early pandemic days when we were acclimating to teaching remotely, but also trying to solve the problem of having no dedicated teaching space at home?) In teaching, this idea rings true, too. As we are learning more about a topic, we may discover a problem alongside our students, and this is the breeding ground for an exciting new project. This is the foundation of problem-based learning. Problem-based learning also offers students real-life learning opportunities, as well as the chance “to think creatively and bring their knowledge to bear in unique ways” (2020 Schunk, p. 64). Problem-based learning can look differently depending on the content and grade level, but often includes group discussions that allow for multiple perspectives on a topic, a simulated situation that involves role playing, or group work that includes both collaborative work and time to complete tasks individually. Problem-based learning promotes autonomous learning, self-assessment skills, planning time, project work, and oral and written expression skills. According to a July 2020 article from the Hechinger Report, problem-based learning has gained tremendous momentum, because it allows students to work more freely and at their own pace — a key advantage when learning remotely. In problem-based learning, the content and skills are organized around problems, rather than as a hierarchical list of topics. It’s also inherently learner-centered because the learner actively creates their own knowledge as they attempt to solve the problem.

Putting the “Problem” into Practice

As former English teachers, we both understand the challenge of putting new professional learning into practice. For teachers who need a refresher on how to design a problem-based learning experience for their students, Problem Based Learning: Six Steps to Design, Implement and Assess breaks down the steps to move PBL into practice as follows:

To help put these problem-based steps into perspective, we can look to our recent work with partners from a high school in the South Bronx. The chemistry team there decided to use an anti-racist lens while addressing a problem that was very real to their students — fireworks. During the summer of 2020, there was a record number of firework incidents in New York City. According to an article in the New York Times, the city received over 1,700 fireworks complaints in the first half of June alone. Our partners used this problem as an opportunity for students to research fireworks from multiple lenses, and imagine how they might present their findings and recommendations to local officials. After all, shouldn’t New York Governor Andrew Cuomo hear from high school students in the Bronx about the effects fireworks have on their communities? Here’s what the framework might look like in this example:

From here, we can imagine the possibilities for this framework, considering how students might address the underlying problem from different perspectives and content areas:

Teaching and learning throughout a global pandemic has presented more than its share of challenges. Out of necessity, tremendous innovation has taken place with the use of technology, pedagogy, and curriculum. With problem-based learning, we can continue this innovation in our classrooms, offering our students opportunities to solve real world problems, demonstrate critical thinking, and collaborate with their peers. We would love to hear what problem-based learning tasks you are designing for your classrooms!

This time of uncertainty can create new opportunities to cultivate 21st century skills.

In 2011, three researchers embarked on a journey to better understand how high-achieving schools around the world were preparing students for the 21st century. Their research took them to seven countries, hundreds of classrooms, and thousands of samples of student work. This seminal research had two significant results: first, the development of the original Global Capacities Framework — an outline of essential domains and capacities that outlines students’ needs in education for the next 100 years; and second, a dynamic, collaborative community of K-12 schools and university partners who appreciated the learning experience so much that they didn’t want the research to end. And that’s the story of how the Global Learning Alliance (GLA) came to be.

The founding members of the GLA — from the US, Finland and Singapore — formed the Governing Board, and the community grew to include delegations from China, Australia, Denmark, Sweden, Canada, and South Africa. With roughly 15 partner organizations and 60 individual delegate members, the community comes together every two years to share promising practices, find connections on global issues, and deepen the research into developing 21st century skills through cross-cultural, project-based learning experiences. Professor Suzanne Choo of the National Institute of Education (NIE) in Singapore — one of the original researchers and the leader of our student research projects — said she is hopeful that these types of deep project work can not only jump-start students’ academic skills, but can be a bridge for students to develop lifelong friendships.

Cross-cultural collaborations

The biennial Global Learning Alliance Summit was scheduled to kick off in New York City earlier this year, with a focus on fostering a sense of student belonging at school. Enter: Coronavirus. As we collaborated with colleagues around the world, we were cognizant that COVID-19 was going to have a major impact on the Asian delegations — but we were hopeful that everything would blow over in a few months, so we proceeded with our planning. (Spoiler alert: it did not blow over.) We began discussing the need to postpone the event on behalf of our partners who were being slammed with cases in late February and early March, and then COVID-19 hit home. Rocked by COVID’s impact on schools, every country has continued to make critical decisions that affect not only students’ learning, but their lives. We’ve learned a lot from one another as we’ve continued our collaborations during this time, and ironically, we’re still talking about the responsibility of schools to create a sense of belonging and connection for students. In fact, this issue seems even more important during a time of disrupted learning. Our approach to implementing cross-cultural projects for students has had a major impact on the development of 21st century mindsets, (outlined in our Global Mindset Framework) that can support students to tackle challenges like COVID-19 in the future. COVID-19 has undoubtedly interrupted the opportunities for the GLA to meet together in person, but it has also reaffirmed the value of cross-cultural collaborations for students, school leaders, and academic scholars. Teachers College Professor Ruth Vinz reflected, “At all levels, what these projects can do is help us to make connections. When we work together, we learn together.” Clarinda Choh, Director of Staff Development at Singapore’s Hwa Chong Institution, believes that cross-cultural projects build a deeper awareness on learning how students learn, helping students and educators to bring attention to their similarities.

Embracing 21st century mindsets

As we reflect on the Global Mindset Framework in light of the current health, economic, and political crisis, it seems more relevant than ever before. In particular, cultivating a Global Consciousness requires us to engage in Real-World Problem-Solving. In many ways, we are living through a case study of what to do — and what not to do —when approaching problem-solving on a global scale. Using current events, media sources, and government responses around the world will be instructive in how we are able to learn from these experiences and support students to develop the problem-solving and collaboration skills they need as they grow into adulthood. At best, these are uncertain and unsettling times. Ironically, one of the 21st century skills that I have struggled with, Appreciating Ambiguity, is the one that’s most needed right now. We are learning to shift our mindsets to hold multiple truths: these are very difficult times, and we don’t know what the long lasting impact will be. In times of great uncertainty, there are opportunities for deep learning, powerful collaborations, and inspiring innovations. We don’t yet know when to expect the end of this global crisis we’re in, but we do know that the best way to get through it is together. That being said, one of the Framework’s skills I’m most inspired by right now is the ability to Imagine. Especially when walking in uncharted territory, it is so easy to become overwhelmed by the pressures and fears within each day. It’s too easy to focus on what should be, rather than on what is. But when we begin to imagine, when we begin to envision what has yet to become, the world of possibilities opens up before us.

Developing social-emotional skills can help students better care for and advocate for themselves and others.

Balancing teaching your curriculum with finding time to discuss with students what they are experiencing and how they are feeling can be challenging. Yet staying connected with them and what they are going through is essential in order to continue supporting them. Students are dealing with many significant life changes and a range of emotions, many of which can be traced back to the shifts they've experienced during the pandemic — worrying about their own health and that of their family members and friends, feelings of loss about missed experiences, navigating a new form of learning, and being confined to their homes with their family members.

Supporting self-reflection

Bringing low-tech self-reflection practices into your classroom can be a helpful way to address the social-emotional needs of your students. Developing social-emotional skills can help students of all ages better care for and advocate for themselves and others. One way of incorporating at least a few minutes of self-reflection into lessons is by using social-emotional prompts (download a full set of our SEL prompts here). Our prompts are organized into several categories, drawn from the core social-emotional competencies identified by the educational research organization the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. Prompts fall into the following categories:

Using these prompts with your students

These prompts can be sent out over email, posted on a class’s online feed, or shared aloud during a real-time class. Students can respond to them in a variety of ways — using tech-free (drawing or writing in a journal), low-tech (typing in a document, making a video recording, making an audio recording, taking photos), or high-tech options (posting responses to a shared classroom file, such as on Google Drive). Before using these in your classroom, give yourself time to engage in your own self-reflection practices (through these prompts or other means) — this will support you in more thoughtfully facilitating social-emotional learning exercises for others. Take the time to introduce the idea of the prompts to your students. You may contextualize the prompts by sharing that they’ll help with self-reflection during this strange period of confusion and uncertainty. For students to fully express their answers, they may not be comfortable sharing any or all of their responses — determine what you think would be best for your students. There is still significant value in students responding to each prompt, even if they choose not to share with others. Below are a few ways that you can use these with your students in your online classes: LOW-TECH

HIGH-TECH

Breaking down the components of creativity so that we can begin integrating it into our instruction.

Some people have a true gift and talent for drawing, painting, sculpting, singing, acting or dancing. We sometimes mistake this talented artistry as creativity. This makes it seem like creativity is something you’re born with, not something you learn. But that’s a myth — there’s a big difference between artistry and creativity. Creativity is about developing the power to make something from nothing.

Our research-based framework for 21st century skills focuses on the creative mindset as one of five essential skills for the 21st century. Let’s face it, in a world where every piece of information is available to us within three clicks of a mouse or three swipes on a phone, finding facts is easy. The biggest needs we anticipate for future success is the ability to use information to innovate and solve complex problems. That takes creativity. As educators, it’s our job to figure out how to teach creativity to our students. In order to teach towards creativity, we have to disavow the myth that creativity is an innate trait bestowed on only the few, and begin breaking down its component parts so that we can integrate it into our instruction. We’ve defined creativity as the capacity for students to cultivate their curiosity by questioning or imagining in order to contribute positive improvements or inventions to their world. We’ve identified four skills that work together to cultivate creativity: imagining, questioning, simulating, and appreciating ambiguity.

Imagining

A vivid imagination is part of childhood development that is sparked around toddlerhood, as children learn about the world through play and pretend. To pretend that something is true, when it isn’t, for the purpose of exploration and understanding (as opposed to deceit — which would be lying, or as a joke — which could be satire). We've outlined three simple entry points to incorporate imagining into instruction:

These are not the only entry points, but they should be accessible to us at multiple levels of instruction, and across different content areas.

Questioning

Like imagining, questioning is also a normal part of human development that emerges as early as some children can talk (the classic, “why, why, why, why?”) and often lasts through early elementary school. Once in school, this skill often atrophies as traditional methods of teaching are structured such that the teacher asks the questions and the students answer, rather than having the students ask questions and work together to explore possible answers. Asking questions is a key factor of curiosity, and curiosity is a key level towards creativity and problem solving. Let's look at three entry points for supporting students to being asking questions, rather than simply answering them:

Simulating

Simulation or embodiments are powerful, physical ways to connect and internalize information though experiences. We will never know what it was really like to be on the Oregon Trail, or to fight in the American Revolution, or to live in a Hooverville during the Great Depression — but through simulated learning projects, we can approximate the experience to gain deeper insights. Whether we’re engaging in a short, impromptu learning activity, or a long term project, here are three entry points for simulating:

Appreciating ambiguity

Whether it’s nature or nurture, as human beings, we’re always looking for the right answer. And in school, we typically reward this kind of thinking. When students believe that there is one right answer, they may fall into the trap that being right is the goal of learning, when in fact, being right means we haven’t learned anything new at all. There is no absolute right answer in real life, and if we can shift our thinking from looking for the right answer, to looking for the possible answers, we shift the purpose of learning from something that is singular and narrow to something that opens us up to new opportunities. Entry points toward appreciating ambiguity:

When we regularly engage our students in lessons strategically designed to support imagining, questioning, simulating, and appreciating ambiguity, they become more and more connected to the topic, and more authentically curious about the process. Their imaginations are sparked with new ideas, innovative solutions, and new questions. Each of these traits works toward developing the mindset of creativity — resilient in the face of challenging circumstances, curious about the world, and confident that there isn’t any problem too big to tackle, or too simple to ignore.

What type of learning experiences do students need to lead in the future?

I recently provided the opening remarks for an institute with international educators about developing a 21st century pedagogy. As part of the talk, I wanted to draw a comparison between how I grew up and how kids are growing up today. I described how, when I was growing up, I had to use the card catalogue to find sources for my research paper, wait for film to be processed before I could see my pictures, and how I learned to type on a typewriter. These all seem like ancient technologies to us now, but it was a good reminder of how much has changed, and how quickly. The impact of these changes has made the world smaller, and more complicated as the advancement of technology has created more opportunities for globalization, instant communication with anyone in any time zone, and insights into the celebrations and challenges people experience around the world.

The reality is that the advancement of technology in the last twenty years has changed our culture in phenomenal and unpredictable ways, and we feel these changes acutely in schools. Whether it’s a challenge around developing and sticking to a cell phone policy for students, competing for time and attention in the YouTube generation, or how all of a sudden we find ourselves saying something like, “kids these days...” followed by something that was disappointing. As educators, we are confronted with the culture shift in powerful ways, and we know we have to do something about it. Many teachers, schools, and even districts have begun adopting the concept of preparing students to be global citizens as we recognize that students who are currently in 6th grade will be 25 years old in the year 2030, and that this generation of students will be the adults who deal with climate change, global economics, and the impact of massive voluntary and forced migrations. So the question becomes, what do kids these days need to learn and be able to do in order to feel prepared for the future where they will be leaders?

Using the Global Mindset Framework

This question is always a motivation for me to think critically about cultivating a curriculum with 21st century skills. In its current iteration, our research-based Global Mindset Framework includes 20 skills and capacities for global thinking that can be used to develop a thoughtful 21st century curriculum by transforming 20th century assignments into dynamic 21st century projects. Using the framework to guide or develop a unit plan or project can quickly transform our curriculum and instruction.

One way we can begin to transform our curriculum is by acknowledging that our current curricula are most often focused on a traditional 20th century set of thinking skills connected to Bloom’s Taxonomy (Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation). Even in spinoffs like Marzano or Webb’s Depth of Knowledge or our own Rigormeter, we see Bloom as the foundational underpinning of most learning goals, content standards, and teacher objectives. This is great, because teaching toward global citizenship or towards 21st century skills absolutely requires students to be logical, rational, and critical thinkers.

Small, deliberate changes