|

Turn the obstacles created by shifting learning styles into opportunities for adaptation and innovation.

When it comes to education, every era has its defining tools and methods, each playing a central role. From the iconic chalkboards that once graced classroom walls to the overhead projectors that illuminated our lessons, these tools were fundamental in shaping our educational approaches. However, as technology continues to progress, these traditional tools are gradually being replaced by more advanced alternatives.

As such, education must evolve to keep pace with these changes, and teachers need to adapt to new technologies and teaching methods to effectively meet the needs of their modern learners. In a world defined by 21st century innovation, we can no longer rely on 20th century teaching methods. Yet, embracing change is no easy feat! In a whirlwind of shifts, resistance often arises, especially from educators who’ve experienced firsthand the loss and excitement of these transitions. Many educators find themselves grappling with the need to let go of cherished beliefs and teaching methods rooted in their own experiences and identities. In my recent conversations with teachers, a common sentiment emerges: the perceived disinterest of students in reading, their struggle with mastering basic skills like multiplication tables, and their apparent lack of engagement in critical thinking. These concerns are undoubtedly valid. However, as educators, we must confront the reality that today's students interact with reading, interests, and motivations in ways vastly different from previous generations. Accepting these changes can be difficult, especially when they seem to highlight deficiencies. But if we examine the changes and evolutions of trusted teaching methods of the past, we can gain insight into how technology continues to shape our ways of living and learning, setting the stage for understanding which teaching methods have become obsolete in today's digital age. The textbook

Modern textbooks became a staple starting in the 15th century. These trusty learning companions were used by teachers and students for generations and were praised for their wealth of knowledge evident in their heavy weight. Carrying a textbook was once a symbol of academic dedication, but in today's digital world, textbooks alone do not suffice. They're too basic for modern learners who want interactive, multimedia experiences, and as technology advances and access to information increases, textbooks just can't keep up with the engaging and personalized learning experiences students need.

The encyclopedia

In the 16th century, the encyclopedia was introduced. It was once praised as the most powerful source of human knowledge, jammed between two hardbound covers. I remember being fascinated by Encyclopædia Britannica and waiting in line to use the limited supply in our classroom. I would turn the delicate pages to find answers to all sorts of questions. But today, hard copy encyclopedias are obsolete. Students now have access to the vastness of the internet for instant information and real-time updates.

Library catalog systems

In the 19th century, we experienced the creation of the modern library catalog system, with its neatly indexed cards and Dewey Decimal classifications. It was once the key to the world of knowledge within a library's walls — it guided students through the maze of shelves, leading them to the books and resources they wanted to read. I distinctly recall my visits to the library, armed with my own shiny library card, seeking advice and assistance from the librarian, and paying fees when I missed the return deadline.

Yet, with the advent of digital databases and online search engines, the catalog system is a symbol of the past, replaced by instant access to a wealth of information at our fingertips. Furthermore, the act of reading itself has undergone a significant transformation. While some still cherish the smell and feel of a physical book, like me, checking out physical books has become a distant memory for many. Many people have embraced the convenience of accessing articles, podcasts, audiobooks, and other digital formats. The act of "reading" has expanded to include a wide array of mediums, reflecting the changing preferences and lifestyles of readers and learners in the digital age. The only constant is change

These transformations reflect the resilience of education in the face of technological advancements, underscoring that with change comes the potential for growth, adaptation, and progress. Librarians have evolved into “digital resource coordinators,” “media specialists,” and “information specialists,” guiding learners through the digital landscape. And traditional book companies have transitioned to online platforms for greater accessibility and customization.

Today, we're facing rapid technological changes, like YouTube, TikTok, and social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. There's also a growing presence of Generative AI, which, like changes in the past, can feel daunting. These advancements are reshaping the learning landscape, with some fearful of the implications for originality and personal privacy, while others view them as an opportunity to revolutionize education by offering personalized learning experiences for every student. The importance of reflection for innovation

I've been encouraging teachers to ask: What are the goals I have for my students? Where do these goals originate, and do they align with the demands of the 21st century? These inquiries prompt us to determine when adjustments are necessary, whether it involves letting go of outdated methods, revising our approaches, or affirming current practices.

Recently, I've observed educators designing innovative and relevant projects that deeply engage their students. These projects often culminate in products inspired by social media or TikTok videos, and sometimes incorporate QR codes for added interaction. For example, in a history class, students were creating short TikTok-inspired videos depicting key historical events or figures, using creative props and costumes to make the content engaging and memorable. These challenges can encourage active learning and collaboration among students, as they work together to brainstorm ideas and produce their videos. In a science class, I witnessed students engaging in a "Science Experiment Challenge" where they were tasked with filming themselves, with help from the technology teachers, conducting simple experiments and explaining the scientific principles behind them. This not only reinforces learning but also allows students to showcase their understanding in a fun and interactive way. In an art class, a teacher had her students showcase their creative projects by creating a series of Instagram- inspired posts including captions and comments, allowing them to document their artistic process from conception to completion. And in an ELA class, a teacher shared how she has been using AI platforms, like Brainly, to provide additional support to her students by offering personalized tutoring sessions, answering questions, and providing explanations on various topics, supplementing traditional classroom instruction. These examples demonstrate teachers’ efforts to stay updated on technological changes and connect with students by leveraging their interests.

Regardless of your sentiments around these shifts and changes, their impact on students cannot be denied. Therefore, it's crucial to shift our focus towards supporting students in developing the skills and competencies necessary for success in the modern world. Rather than viewing students' changing learning styles and interests as obstacles, we must see them as opportunities for growth, adaptation, and innovation.

By meeting students where they are and embracing their unique perspectives, we can foster a learning environment that encourages curiosity, critical thinking, and engagement with the world around them. This approach not only prepares students for the challenges of today, but also equips them with the resilience and adaptability needed to thrive in an ever-changing future.

References

The Journal of American History Textbooks Today and Tomorrow: A Conversation about History, Pedagogy, and Economics Encyclopedia Britannica

Find inspiration for classroom discussions that encourage students to make their voices heard.

“So, what are your thoughts? Talk with each other.”

I remember asking this question many times, always expecting it to be greeted immediately and enthusiastically by the voices of many students, clamoring to share all at once. In some classrooms, that was the case. In most others, a deafening silence would stretch for several minutes. Eventually, I’d ask a new question or encourage them to write down their answers and turn them in so that I could read them. Most students had an abundance of thoughts, I discovered, when they handed in their written responses. I desperately wanted to create a culture of discussion in my classroom, one in which students could not stop talking to one another about our texts and topics of study. But, this open-ended question asking them to share their thoughts never seemed to stimulate the kind of discussions that I was searching for. The question for me became, how can I begin to create a culture of discussion in my classroom?

Questioning

To explore that larger question, I began with a smaller one: what kind of questions were the most exciting for me to answer as a learner? We all may have different answers to that question, and I encourage you to take a few moments to think or to write about what your unique answer might be. In my own process of reflection, I discovered that I am enthusiastic to answer questions that are open-ended: those that invite many different perspectives and clearly do not have one “correct” answer. I also love questions that get me thinking about something that hasn’t occurred to me before: thought-provoking questions that feel relevant to me in some way, connecting to my interests, my recent thought patterns, or some facet of my identity. And, most especially, I love answering questions when I can be assured that someone else around me will answer, too. There is something vulnerable about sharing thoughts and ideas in a classroom space, especially when there is no guarantee that others will do the same. Out of my own reflections came clear pathways forward — new things to try.

Paired discussion

The first protocol that I embraced consistently became the turn and talk. Rather than invite students to share in front of the whole class, I’d invite students to turn and talk to one person next to them, taking turns to share their responses. I can appreciate how many teachers mock the turn-and-talk discussion protocol as a favorite of administrators who believe that this discussion technique will solve all educational dilemmas. As teachers, it can be easy to become cynical quickly about those strategies most commonly suggested. With that said, the turn-and-talk protocol transformed academic talk in my classroom. By the third or fourth time that I implemented the strategy, I was stunned by all the ideas my students were willing to share with each other that they wouldn’t share with the whole class. But, it also made sense once I implemented the protocol, as so many things in retrospect often do. It’s much easier to share with a peer than with one’s teacher. It’s much easier to share with a peer when you know that they will share in return with you. Eventually, I knew that I wanted the turn-and-talk to grow into small group discussions. So, how?

Small group discussion

“Save the Last Word for Me” was introduced to me by a colleague who was devoted to building a culture of discussion in her classroom. Her explanation was simple, and I do my best to recreate it here:

I never implemented the protocol to fidelity, but it inspired lots of small group discussions in my classrooms. What if I tried it with images? With documents? With word problems? What if the groups were slightly larger or smaller? To me, one beautiful thing about teaching is that every protocol is an invitation to create and to re-create things until they feel like our own. I invite you to do the same — what small group discussion strategies might this one protocol inspire?

Whole class discussion

I never gave up on my dream of whole class discussions. As many English teachers can appreciate, the Socratic seminar is often celebrated as the pinnacle of literary discussions. After many months of paired and small group discussions, I was terrified that our first Socratic seminar of the year would be a return to the silence. Students are always full of surprises. “But did you look here at what she says on page 23? It makes me think that….” “I’m not sure I agree, but that’s an interesting point. Have you thought about….” “That’s a good point. Maybe we should think about….” The voices, the laughter, the thoughts swirling around — it was everything that I had hoped for my students in a whole class discussion. I described this moment of success with a fellow teacher, expressing my surprise and amazement about how successful our first Socratic seminar was. He laughed, “I’m not surprised. Your kids are always talking.”

An invitation

Creating a culture of discussion was not a linear experience for me as a teacher. I learned from the wisdom of fellow teachers and, no matter what protocols I used, there were days in which silence felt inevitable. But, I did get my students talking. If you’re interested in thinking more about how to create a culture of discussion in your own classroom, I invite you to join me online at Keep the Kids Talking, where you can reflect on your own experiences, and also acquire new, implementable discussion strategies. I hope to see you there.

Encourage meaningful reading habits as you ask students to engage in a dialogue with their text.

Over the past few years, I have heard more and more middle and high school teachers agree about how difficult it is to “get kids to read." I have observed myself that few students seem to be reading full length books independently, and by choice. Of course, there are so many reasons for these observations.

Let’s zoom out a bit to think about the state of reading for most of our students: in the past, reading was not only a major form of entertainment, but a crucial source of information. Time for reading was not in competition with an expansive, alluring digital world offering games, web surfing, Tik Tok, Instagram, endless TV and YouTube channels, etc. Even as adults, we know how easily accessible and comforting these modalities are. Technology offers us so many easy, even addictive options. Technology has also made it easier for students to “read” or pretend they have read an assigned text by scanning summaries of chapters, Googling quotations from the text, watching video versions, etc. Information that we may have needed to access by reading a book is now available at the click of a finger or by saying a few words to AI. We have all been there — we even have a term for this, tl;dr, or too long, didn’t read. Research confirms my own observations that few young people are reading on their own or consider “reading for pleasure." The Pew Research Center asserts that, “few late teenagers are reading many books” and a recent summary of studies cited by Common Sense Media indicates that American teenagers are less likely to read ‘for fun’ at seventeen than at thirteen.” The pandemic also seems to have derailed some students’ academic reading habits, which have proven to be like muscles that need to be exercised more regularly than we previously knew. All of this means that if we want our students to read, to become strong, confident readers, and maybe even enjoy reading, it is crucial for educators to make reading meaningful and relevant for our students, and not simply “cheat proof."

Encouraging students to read

Offering students choices of relevant books to read and discuss together in book groups or pairs is a fantastic way to encourage them to engage in reading. However, most educators agree that reading a book together — as a shared “anchor text” for the whole class — can also be important and lead to powerful discussions and collective learning. Mike Epperson — a teacher with whom I work closely in the South Bronx — took the opportunity to bring a shared anchor text to his 10th grade classroom, introducing his students to Elie Wiesel’s Night. While Night is a riveting, significant story and a relevant choice for 10th graders, who are concurrently learning about World War II and the Holocaust in history class, that doesn’t guarantee that students will engage in the reading. Mike was concerned about ensuring that his students were both engaged deeply and personally in the important subject matter and took it seriously. He decided early on that he wanted students to read the entire book. Mike strategically layered his teaching unit with Night at its core, along with supports and entry points to encourage high engagement, including: background building about the Holocaust, Anti-Semitism, and Judaism, and a careful sequence of lessons that focused on a key topic in a section of the book. Additionally, to encourage reluctant or less confident readers to read daily and remain engaged in reading the whole book, Mike emphasized and taught annotation. Since the school had copies of the book left over from ordering during the pandemic, Mike was able to give each student their own book to write in and keep. These two simple pieces — students having a book of their own and an opportunity to talk back to the text through annotation — created an environment ripe for close reading and high engagement.

Encouraging students to annotate

Getting students to annotate in their actual books wasn’t as simple as Mike had expected — he recalls that “when we first started annotating, some students expressed resistance because they didn’t want to make the nice-looking book look ugly. One student compared it to writing on a beautiful painting with crayon.” However, as time went on, students were “able to find a way to annotate that helped them preserve the beauty of the original text. I believe that as students took on a self-appointed role as the book’s preservationists, they ended up developing a deeper respect for the content of the book as well.” As the students connected more personally with the book and the character of Elie, Mike began to see that the act of authentic annotation was offering students an unanticipated opportunity for creative expression. He shared that “a lot of students like drawing, and there’s a similar appeal in annotation. While annotating is not drawing, a fully annotated page is visually pleasing. Some students’ annotations are neat, symmetrical, and visually appealing in a way that suggests that students take pride in how their annotations look. I think this fosters a sense of pride in the content of their annotations, too.” Mike’s observations of his students’ annotations confirm the belief that writing as you read makes your thinking visible, and can create an engaging conversation as we talk back to the text. He puts it simply: “Annotation gives the students a more active role in reading. They get to have a voice, even if no one else will see their annotations.” The students are no longer alone with a book. They are in dialogue.

Suggestions for successful annotation

When I visit Mike’s classroom, students eagerly show me their annotations and explain the significance of both specific lines on a page and their connections to larger themes. A number of students also tell me how much annotation is helping them “remember’ and “understand” past parts of the story. They are clearly proud of their text marking and meaning-making. Based on my observations of Mike’s classes, I’d like to offer some simple tips for making annotation a successful approach with your own students:

Hopefully, you will feel inspired to introduce or continue using annotation in your classroom! As you encourage students to read with their pen and engage in a dialogue with a text, feel free to adjust any of the strategies above to match the readers and annotators in your classroom.

Four ways to cultivate student connections through stories, personalities, and interests.

It’s the first few weeks of school. New students are entering our school’s hallways and sitting in our classrooms. Fresh paper, pencils, and (hopefully) charged computers are perched on desks. Awkward glances and shuffling feet and uncertain pauses fill the air. As teachers, we are faced with this challenge: how do we begin to build a learning community in our classroom, one that invites trusting dialogue and encourages intellectual curiosity?

I often received one, seemingly simple answer: “find a good icebreaker.” An icebreaker is an activity or engagement task designed to get people talking and learning about one another — in other words, a task to “break the ice” of social awkwardness. A fellow teacher in my school swore by “Would You Rather?” as the icebreaker that had withstood the test of time, asking students to answer a series of extreme either-or questions like, “Would you rather fight a bear or a shark, and why?” I don’t think there’s one best icebreaker for all students or for all teachers. It’s difficult to know definitively what will resonate with your particular students. With that said, I knew that it was possible to find an icebreaker that invited students to get to know each other in a meaningful, personal way. Below you’ll find four activities that will help you “break the ice” with your new students and begin creating genuine connections within your classroom community.

The Neighborhood Map

Discovering & Writing About a Memory This first activity, invites students to make a memory map of their childhood bedroom, apartment, house, or neighborhood. Then, it asks students to look for stories they can share, inspired by places marked on their map. The memory map was developed by Stephen Dunning in the early 1970s and later articulated in his book Getting the Knack (1992). His workshops led to other educators across the country creating various versions of this practice, including by members of the South Coast California Writing Project. Ask students to draw a birds-eye view map, then “walk” a partner or small group through descriptions of the places on their maps. After doing so, students number and label these “story places” on their maps and choose one story to write about further. Students are invited to share their written story in a partnership or in a small group. For younger students, I encourage using some sentence starters to scaffold the sharing process, such as “This place stays in my mind because…” or “The important thing about this story is…” A possible set of directions are included here and here, but I encourage you to develop directions that will work best for you and for your students. For those who may not feel comfortable drawing their own memory map, perhaps imaginative or fictional map drawing could accomplish a similar goal of learning about your students. If writing is a central component of your classroom, consider transforming this activity into a writing benchmark for your students at the beginning of the year to gain insight into their writing abilities. This activity can work in an elementary, middle, high school, college, or even adult-education setting, and is especially inclusive for English language learning students, given the opportunity to tell stories through drawn visuals.

The Cultural Tree

Getting to Know Yourself and Your Students In this activity, students are asked to create a “cultural tree” that represents their culture. Originally envisioned as part of Zaretta Hammond’s work in Culturally Responsive Teaching & the Brain, the drawing of cultural trees asks students to identify three levels of their culture: surface level — aspects of culture you can see like food and dress, shallow culture — aspects less explicit, like concepts of eye contact and personal space, and deep culture — unconscious beliefs and norms like concepts of fairness and spirituality. My colleague at CPET, Lauren Midgette, has used Hammond’s work to write and to reflect on the possibilities it has for getting to know students, but also ourselves, better in the classroom this school year. Midgette makes the point that the drawing of cultural trees — and the discussions inspired by them — provides a healthy soil to help our students grow. Each level of culture — surface, shallow, and deep — is visualized on the tree as leaves, trunk, and roots, respectively. For younger students, I don’t think the framing of the tree as “cultural” is necessary for the activity to be an effective tool for discussion. Students could certainly label a tree with aspects of who they are that are surface (easily seen by others), shallow (not as easily seen), or deep (entirely unseen).

Telling a Story Through An Object

This third activity requires slightly more teacher preparation than the first two, but is one that I have found particularly effective with students of all ages. I created the directions to facilitate this activity — linked here, but the premise was inspired by fellow educators: objects, even the most simple ones, are imbued with our stories. First, find an ordinary cardboard box. Label it “mystery box.” Next, fix it with a bunch of objects — they can be commonplace things like birthday candles, hair ties, or chewing gum — or more particular objects, like sports paraphernalia or local fruits and vegetables. Lastly, close it and place it in a very visible place in the classroom and say nothing about it to your students until you begin class. Explain to students that inside the box are a bunch of objects that you will pull out one at a time. As soon as students see an object that reminds them of a story, memory, or experience, encourage them to start writing that story. The final thing that I pull out of the box is a slip of paper that says, “the object that you were hoping I was going to pull out.” It’s a catch-all invitation for students to write about an object close to their heart that you may not have been able to acquire. Invite students to share their stories with one another after they have written them. In my facilitation of this activity, I found that students often worried that their story wouldn’t be “good” or “significant” enough. I explicitly invite ordinary stories from students, which have never been “ordinary,” but rather extraordinary insights into the students and their backgrounds and interests. As the year progresses, I invite you to experiment with this activity in the reverse: invite students to bring in their own meaningful objects that have a personal story attached to them to add to a classroom box. They can share their objects and stories before placing them into the box.

Beginning With A Two Sentence Story

The fourth icebreaker requires no teacher preparation and the prompt for students is incredibly simple: write the beginning of a two-sentence story from your day today. This activity, as well as these questions, were introduced to me by Professor Ruth Vinz at Teachers College, Columbia University. Invite students to write in the present tense as a means to place themselves back in the moment they are writing about. Remind students that the purpose is not to assess their writing skills, nor to write the most significant story possible. The story starter can be simple, so long as it is about some event from their day. This icebreaker would work especially well for an afternoon class. Alternatively, the prompt could be modified to read, “write the beginning of a two-sentence story from your day yesterday. Even though the story happened yesterday, please write in the present tense, as though you are living the story at this very moment.” After writing their two sentences, invite all students to read them aloud in no particular order and without any further explanation. Next, invite students to consider how their stories might be threaded or connected together. Consider these facilitation questions:

Dive a Little Deeper Under the Ice

Icebreakers can be wonderful ways to start connecting with new students — they alleviate nerves and provide an entry point for relationship building. This year, I invite you to not only “break the ice,” but also to dive a little deeper under the surface, creating ways for students to connect in genuine ways through their stories, personalities, and interests. Please modify these activities — they are intended to be transformed for you and your classroom. And the best part? These activities can be used at any point in time to learn something new about your students.

Engage students in rich mathematical tasks that honor the process more than the solution.

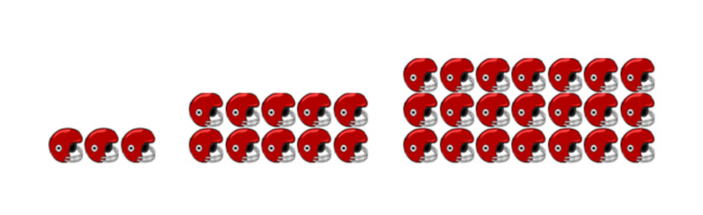

I was recently sitting with a high school algebra teacher — who was preparing a lesson about translating sequences into functions or equations — and trying to encourage him to use this archive of visual patterns with his students. We discussed matching different groups of students to different images and asking them to try writing an equation for the pattern. As the teacher started practicing on his own, writing equations for some of the patterns that were offered, this picture came up, and we both began to struggle.

Neither of us could figure it out.

Other teachers started coming by to join: “There has to be an exponent in there somewhere...” “But just an exponent wouldn’t make sense…” “Are we multiplying the exponent? Or maybe multiplying and adding?” This had started with only one teacher, but soon there were five teachers huddled around this image, trying to find a solution. One teacher got out a marker and began writing possibilities on the board. Another started running through calculations in their head, shouting out theories. Finally, one teacher said, “Oh, it’s a quadratic!” The algebra teacher who had started with me stated, “see I can’t do this with my students, we couldn’t even figure it out”. But I had the complete opposite reaction. I was surprised at how many had engaged in our puzzle. We were all trying out different methods, debating and discussing throughout our process. This is what a math classroom should look like every day.

Making room for authentic engagement

As math teachers, it can feel scary to introduce a problem to students that doesn’t have a clear and simple solution. But how else is authentic math engagement supposed to happen in the classroom? In our example, even if we had never arrived at a solution, all the math thinking and practice we did to try and get there would have been worth the struggle. Even if a student never achieved a correct equation or solution, they still would have stretched their thinking and understanding of patterns and functions just by trying to work through the task. The inspiration for this task came from Jo Boaler’s work on Mathematical Mindsets. In her book, she reminds us how beautiful and rich mathematical thinking can be, and offers advice on how to bring that into your classroom. This task we were testing out among teachers includes many of the suggestions she offers for making rich mathematical tasks. Boaler describes these tasks as having multiple entry points, visual components, and options for inquiry and debate. As you incorporate these elements into the math tasks in your classroom, consider the following questions as you shift into a richer mathematical lens:

Our original task starts with a visual component and includes multiple methods of entry. Students have the opportunity to make sense of the visual in any way they see fit — maybe they prefer to focus on the numbers, or maybe they want to look at the way the shape of the image is changing. There are no clear steps to follow to solve this puzzle; students have to play and engage in multiple ways before they can predict patterns and solutions. Another great aspect of this task is that students of all math levels can participate and still walk away learning something from the experience. Maybe some students will leave noticing there is not a constant amount of change between the pictures. Maybe some students will consider the way addition and multiplication look different in patterns. Maybe some students will write a quadratic equation and then be able to predict future images. The possibilities are endless.

When we provide math problems that have very clear and explicit steps, we may lead students to the correct answer, but we also limit the creativity they can experience. We teach students that there is a right and wrong way to do math. We contribute to the negative feelings and attitudes many students already have about math. And lastly, we take away the fun.

Making room for rich mathematical tasks that have multiple entry points, opportunities for debate, and visual components can help make every student feel like they can one day be a real mathematician. It can help students of all levels rediscover the fun in math.

Encourage students to expand their repertoire of ways to read and respond to literature.

As someone who loves to read and write, one of my favorite things to do is annotate texts — whether it be a few scrawled words in the margins of my most beloved hardcover books or endless questions written on sticky notes falling out of flailing paperbacks, my annotations capture the spirit of my hyper-personal engagement with a text.

When I became an English teacher, I knew that I wanted my students to learn how to annotate, in part because I wanted them to capture their noticings and wonderings as they engaged in their own distinctive reading process. In “Literature as Exploration” (1995), Louise Rosenblatt wrote that every person has a unique, transactional experience when they read a text, in which they “live through” something special. I think of annotations like mementos of this special reading experience because they capture a moment in time in the transactional experience that would otherwise be lost. Every time we read a text, even if it’s one that we’ve read hundreds of times before, we encounter a new transactional experience. As we annotate and re-annotate texts, we leave behind a trail of our reading experiences: our questions, thoughts, and wonderings. I desperately wanted my students to develop that experiential, transactional trail of their reading processes.

The Traveling Text

Imagine my surprise when I discovered, as a new teacher, that my students often responded to my call for annotations with, “I don’t know how to annotate!” or “Can you tell me what to annotate for?” or, worst of all, “I hate annotating. It’s a waste of time.” I can recall my naive shock when I heard my students respond in this way. In a desperate attempt to show my students the value of annotating, I began tirelessly modeling annotation strategies and my own methods of annotation, but doing so yielded little success. With time, I developed an incredibly simple strategy for teaching my students to annotate. Essentially, I stopped teaching my students to annotate through direct instruction and, instead, encouraged them to teach one another. This instructional strategy was, in my teaching, a solution to the problem of students feeling like they “don’t know” how to annotate or that annotating has “no purpose.” I call this strategy The Traveling Text (download here). The Traveling Text is simple, requires minimal teacher preparation, empowers students, builds community, and teaches annotation skills. And implementing this strategy with your students only takes four steps.

The impact of The Traveling Text

In my teaching experience, here are some of the impacts of this strategy on my students and our classroom community:

Teaching students to read for meaning (and for pleasure) is a daunting task. Often, our students come to us already feeling like they don’t know how to read and annotate literary texts in the “correct” way, one that highlights what a teacher or evaluator might be looking for.

The Traveling Text creates possibilities for students to expand their own repertoire of ways to closely read and respond to literature. But, even more importantly, the strategy encourages students to experience a sense of intellectual community and belonging with their classmates as they share with one another written artifacts of their own transactional reading experiences.

Build a classroom culture that encourages active listening and a willingness to consider others' perspectives.

When I was a middle school English Language Arts teacher, I often asked my students to engage in debates inspired by our readings. For example, I once asked my students to read Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” — a short story in which a group of villagers participate in a long-standing tradition of stoning to death the “winner” of a mandatory lottery — and to debate whether or not the villagers could be considered “murderers.”

The prompt for students to “debate” with one another had its benefits: my students often became passionate to defend their beliefs and their analyses of the text, and students read the text closely to identify evidence and to justify their thinking out loud. However, notable shortcomings also arose when students engaged in the task of debate: they often became combative and indignant when others did not agree with them, and they seemed resistant to change their initial side of the argument. At any age, it can be challenging for students to admit that they have changed their minds, especially in front of their peers. Even moreso, it can be challenging for students to actively listen and to respond to others’ points of view and analyses. It requires the ability to welcome or to accept a new idea or perspective. An excellent way to foster this kind of openness in the classroom — this culture of intellectual and social empathy — is to ask students to participate in what Peter Elbow called “The Believing Game.”

Balancing believing & doubting

The task of debate often asks students to participate in what Elbow called “The Doubting Game.” The doubting game requires students to be skeptical and as analytic as possible. It encourages students to try hard to doubt ideas, to discover contradictions or weaknesses, and to scrutinize and test others’ logical reasoning. This kind of critical thinking can be incredibly valuable, but it can also foster a classroom culture that only celebrates doubting, whether that be doubting ideas presented in a text or ideas presented by others in the classroom space. Contrastingly, “The Believing Game” asks students to try to be as welcoming or accepting as possible to every idea they encounter: not only to listen to different views, but also to hold back from arguing with those different views. Further, the believing game asks students to restate others’ beliefs or arguments without bias and to participate in the act of actually trying to believe them. Elbow points out that “often we cannot see what’s good in someone else’s idea (or in our own!) till we work at believing it…when an idea goes against current assumptions and beliefs — or if it seems alien, dangerous, or poorly formulated — we often cannot see any merit in it.”. Including the believing game in your classroom does not need to coincide with the removal of the doubting game. The act of doubting — of critically thinking to develop thoughtful skepticism — is an undoubtedly important skill for students to develop in order to discern truth. But, a sole focus on doubting, as I shared from my own teaching experience, can lead to a classroom culture in which students are always inclined to doubt. This inclination can lead to rigid thinking, and an unwillingness to listen, respond, and grow. At its worst, this inclination can lead to a classroom culture in which students become hostile towards other students’ beliefs or ideas that seem oppositional to their own.

The benefits of believing

Peter Elbow, the creator of the believing and doubting games, is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He has written extensively about the benefits of methodological believing for students and teachers. He identified three main benefits for the believing game in classrooms:

Engage students in the game of believing

The opportunities for students to participate in the game of believing are endless. I offer here a few suggestions for simple ways to engage students in the game of the believing.

How to implement discussion opportunities that help students solidify their learning and connect with peers.

We’ve all had moments where getting students to talk has not been a problem, but when it comes to academic conversations in the classroom, it can be hard to keep the conversation going. Students might be unsure of where to go next, how to change the topic, or even questioning what discussion is good for. Educators might be asking themselves the same questions! What are the advantages of discussion in the classroom, and how can we encourage students to facilitate their own meaningful conversations?

Why discussion?

First, let’s talk about the importance of discussion. In their book, Academic Conversations: Classroom Talk That Fosters Critical Thinking and Content Understandings, Zwiers and Crawford note that conversations foster all three language learning processes: listening, talking, and negotiating meaning. Not only can these skills be found in the Common Core State Standards (CCSS), but they are also skills we use every day in our own conversations, whether they are academic in nature or more casual. Conversation opportunities give students an authentic space to practice new vocabulary, solidify content learning, strengthen argumentation skills, and connect with their peers. Discussions also need to be connected to some rigorous questions. What makes a rigorous question? Check out the work of my colleagues Jacqui Stolzer and Dr. Laura Rigolosi to explore how one high school is constructing their own definition of rigor, in service of developing high expectations and meaningful work for their students.

What can I do to encourage discussion?

As educators, we can purposefully build these conversation opportunities into our lessons, and even beyond that, we can highlight and model talk moves for our students. Parsing out ways to make a conversation meaningful and creating a guide for students can be a powerful way to ensure they are not only learning content through discussions, but becoming effective communicators as well.

Where do I start?

Below is an example of how you can start to plan, practice, and implement more student-led discussions in your classroom.

After you’ve had time to practice a few different discussion skills, put them together. Consider pairing students with roles; is someone practicing the role of “Devil’s Advocate”? How about moving the conversation forward when there seems to be a lull? The more students practice these roles, the more natural they will become.

Don’t have the time? Teaching is more than a full-time job, so if this seems like something you really want to try but you just don’t have the time to go through all the skills yourself, check out the work done by Uncommon Schools in their Habits of Academic Discussion Guide. You can also check out Keep the Kids Talking, which offers self-paced opportunities to examine questioning & discussion practices and receive feedback from our coaching team. Happy discussing! 10/31/2022 Centering Students for Literacy Engagement: Teacher as Interdependent Curator & Bridge-Builder

Exploring the connection between instructional autonomy and student engagement.

Excerpted from Centering Students for Literacy Engagement: Voice, Choice & Identity, A Review of Literature for Behind the Book, conducted by the Center for Professional Education of Teachers at Teachers College, Columbia University.

Teachers who engage in the design of their own instructional goals understand the direct link between engagement, literacy, and content knowledge. They understand that when students are engaged, there is no limit to their learning, which is why it is such a powerful motivator. Teachers are also keenly aware that how they create visible and invisible space for learning to take place has an impact on student engagement. Everything from how a classroom space is organized, decorated, and maintained has an impact on how well students can physically interact in the space. Relationship building is also critical in the classroom, and the research indicates that fostering non-evaluative literacy experiences creates opportunities for students and teachers to more deeply engage in reading and writing.

Essential factors in engagement

In a research review on literacy engagement, produced by The Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) in collaboration with Behind the Book, we analyzed previously published reviews of literature and research studies on literacy engagement. Throughout the literature, student voice, agency, and confidence emerged as essential factors that lead to increased literacy engagement over time. While many attributes contributed to increasing student voice, choice, and agency, six high leverage areas surfaced: student voice, student agency, student confidence, teacher autonomy, learning environment, and relationship-building. Refer to our companion article to read about Student Voice, Choice & Identity. How do you incorporate these in your practice? What support might you need to deepen your understanding and implementation of these attributes?

Teacher autonomy

Decision-making ideally involves all stakeholders in a school community. The unique role of teachers positions them as professionals in their content areas and the consummate experts of their own classrooms. There is a strong connection between student engagement and how a teacher perceives themselves as authors of their classroom spaces — especially when it comes to teacher autonomy. The concept of professional independence and decision-making is central to motivating teachers to think critically about what, why, and how they’re engaging with their students, which increases their sense of personal and professional responsibility. Teachers navigate their choices within the systems and structures of their districts, school, and department. Educational policies affect the everyday experience of teachers and can construct barriers to teachers exercising autonomy in their classrooms. The shift away from autonomy and professional freedom in K-12 schools has had a dramatic impact on teacher engagement, creativity, and organic professional evolution. Policies that acknowledge teachers as experts will implement systems and structures designed to increase decision-making opportunities on every level, from classroom to school to district. Teachers immersed in the design of their own instructional goals understand the direct link between engagement, literacy, and content knowledge. They understand that when students are engaged, there is no limit to their learning, which is powerful for both teacher and student. When a person has a high level of efficacy in their work, they believe that their time and effort will result in a desired extrinsic or intrinsic reward. For educators, autonomy and efficacy go hand in hand. Teachers are most effective when they have autonomy (decision-making power and the professional responsibilities that come with that power) and efficacy (the belief that their time and effort will generate their desired reward). The effort and self-determination of teachers contributes to their own sense of autonomy and to their students’ success. Teacher autonomy is not something that can be developed overnight, especially in communities where there has been tight control on curriculum, instruction, or teacher style. Schools or districts looking to increase teacher autonomy may want to make an investment in professional development for teacher leaders. Starting small and then building with a team is a great entry point to increasing autonomy for some, and creating a sustainable process for others to develop more autonomy. It is important to remember that teacher autonomy does not mean everyone does anything they want at any time, but rather that teachers are able to exercise professional freedoms for instructional and curricular choices focused on the responsibility of meeting students’ needs. This process can be developed and replicated. Schools interested in developing teacher autonomy can first focus on Department or Content area or grade level teams and develop a structure for meeting together, facilitation, and shared research. As teachers learn more about their field, they are better equipped to make decisions grounded in research. Instructional autonomy leads to the creation of a dynamic learning space, an increased growth mindset and a mindset towards social justice.

Learning environment

If we think of the word environment, as in habitat or place, the learning environment becomes the space where learning takes place. Curating a positive learning environment requires educators to consider how students learn best, under what conditions their learning can be maximized, and what disrupts the learning environment. Once these questions are answered, educators must use their available resources to design the physical or virtual space to create that environment. It’s important for teachers to think critically about creating a space for each student that provides access to resources, manipulatives, and intellectually stimulating tasks. This is commonplace in most elementary school classrooms which utilize their classroom spaces for strategic academic interactions — like the reading rug, the classroom library, and the conferencing table for students to work with their teachers individually or in small groups. All teachers create and cultivate learning spaces in how they interact with their students, how they utilize the space they have, and how they invent ways for students to interact with texts together. Rituals and routines play an important role in creating a learning environment that increases student literacy engagement. With a specific eye towards supporting English Language Learners, we can think beyond the physical resources found within a classroom space and focus on having a mindful routine, creating dynamic personal relationships between stakeholders, and developing instructional materials that are culturally and cognitively responsive to students. Additionally, when surrounded by physical texts and images of texts in the classroom spaces, students are more likely to engage in reading on their own. Implementing discussion is an integral part of the reading and writing process. When students discuss what they’ve read with their peers, it enhances their understanding, and their interest in the text. When students spend time and effort in retelling what they’ve read, creating a response to their reading, or synthesizing the text in new ways, their energy and effort has a direct correlation to their engagement in the reading itself. School and district leaders can support teachers to think deeply about their learning environment by being explicit about the resources available to teachers, as well as clarifying a theory of action that articulates how students learn best and translating that theory into an action plan for the learning environment. Beginning with the theory of action, schools that take the time to develop a shared understanding and a shared approach to learning also reap the benefits of a faculty and staff who are aligned in their mindset and approach and as a result create culture and environment quickly. After articulating the theory of action, schools need to develop an implementation plan, and an accountability plan. How will they see their values come alive in the daily interactions across the school? How will they hold teachers and other school staff members accountable to their ability to translate vision into action? Resources may vary, but the constant in any educational setting are teachers and students, together.

Relationship building

Relationships support building bridges between challenging content and critical skills. The relationship provides an avenue for teachers and students to bridge differences and bond through shared experiences. These bonds become a highway for academic support and interventions. Teachers with a high level of professional freedom typically have the confidence and the creativity to create a positive and engaging learning environment, which will in turn create personal and social spaces for students to find themselves as readers. Those personal and social spaces are nurtured through student-to-student and student-to-teacher relationships. Sharing reading ideas is especially motivating for students. Whether there are formal or informal conversations, teachers and students who read and discuss shared texts create shared experiences and shared memories. These experiences create strong bonds between teachers and students and inform their identities as readers and writers. When teachers and school leaders want to increase engagement through relationship building, focusing on social-emotional learning can be a great entry point. Creating spaces for students and teachers to identify their feelings within a given assignment can avoid misunderstandings that develop hurt feelings and divide teachers and students, impacting culture negatively. For decades, teachers have found that stories are ways to connect students to themselves, to each other, and to their larger community. Reading and writing are both connected to an audience which makes the act of either an experience in connection. Supporting students academically must include supporting students relationally. When students are able to connect with themselves and their classmates; when they connect with their teachers and count them as caring adults in their lives, they have essential support to then connect with texts that will become the driving force of their learning. The real and deep need for strong relationships is a key component to student engagement in reading and writing.

Download the white paper: Centering Students for Literacy Engagement: Voice, Choice & Identity, A Review of Literature for Behind the Book, conducted by the Center for Professional Education of Teachers at Teachers College, Columbia University.

About Behind the Book

Behind the Book was founded with an instinctive sense that getting kids excited about reading could have a significant impact on their academic (and nonacademic) careers, encouraging depth and freedom of thought, a hunger for knowledge and an understanding and appreciation for worlds beyond the one they know. In the years since Behind the Book began scheduling author visits, programming has expanded and evolved to include art projects, field trips, dramatic activities, the publication of student anthologies and more. About the Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) Sponsored by Teachers College, Columbia University, internationally renowned research university, CPET is a non-profit organization that is committed to making excellent and equitable education accessible worldwide. CPET unites theory and practice to promote transformational change. We design innovative projects, cultivate sustainable partnerships, and conduct research through direct and online services to youth and educators. Grounded in adult learning theories, our six core principles structure our customized approach and expand the capacities of educators around the world.

A look at high-leverage areas for student engagement in reading and writing.

Excerpted from Centering Students for Literacy Engagement: Voice, Choice & Identity, A Review of Literature for Behind the Book, conducted by the Center for Professional Education of Teachers at Teachers College, Columbia University.

When it comes to compliance vs. engagement, we can generally agree that compliance is about conforming, yielding, adhering to cultural norms, and cooperating or obeying. Compliance is focused on a mindset of teachers (or adults) having power over students, rather than empowering them. Whether we’ve recognized it or not, many schools are dominated by compliance-oriented structures which often mimic the behaviors of engagement. When schools structure how students enter, exit, move throughout the building, where they sit, how they sit, when they can go to the bathroom or eat food, the learning environment is dominated by a power-over culture which has an impact on authentic student engagement.

Engagement, on the other hand, is more difficult to define. Research on engagement and theories of engagement date back over 50 years and come primarily from perspectives in the fields of psychology and sociology. Each field has contributed theoretical frameworks designed to articulate what engagement is, how it works, how engagement breaks down, and how to generate it. We may understand the theories behind engagement, but can we articulate what engagement looks like for students in school, with respect to literacy through reading and writing specifically? A focus on literacy engagement is critical because without a personal and intrinsic motivation to read or write, school becomes a space that stifles student growth and prioritizes compliance over engagement. When students can develop a personal, authentic engagement in reading (taking in information and ideas) and writing (expressing information and ideas), students can develop sustainably positive experiences in school that develop their self-efficacy and self-confidence.

Essential factors in engagement

In a research review on literacy engagement, produced by The Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) in collaboration with Behind the Book, we analyzed previously published reviews of literature and research studies on literacy engagement. Throughout the literature, student voice, agency, and confidence emerged as essential factors that lead to increased literacy engagement over time. While many attributes contributed to increasing student voice, choice, and agency, six high leverage areas surfaced: student voice, student agency, student confidence, teacher autonomy, learning environment, and relationship-building. Refer to our companion article: Centering Students for Literacy Engagement: Teacher as Interdependent Curator & Bridge-Builder to read more about teacher autonomy, learning environment, and relationship building.

How do you incorporate these in your practice? What support might you need to deepen your understanding and implementation of these attributes?

Student voice

Student voice can be cultivated through classroom culture, through reading, and through writing. Classroom culture accumulates the small, large, formal, and informal ways that students interact with one another and their teachers. Here, when their voice is either heard or silenced, it has an impact on how the student engages in classroom activities and tasks. Educators find ways to elicit student voice intentionally by creating windows and mirrors. Windows are opportunities for students to see themselves in the literature they’re reading. When teachers design prompts that help students make connections, find commonalities, or empathize with characters or situations they’re reading, they create a metaphorical window for students to see how they connect with a text. Alternatively, teachers can also prompt students with entry points to reading and writing that act as mirrors for students to see their thoughts and feelings emerge on the page as they write or draw. Mirrors reflect our identity, and mirroring tasks and texts give students an opportunity to see themselves as valid, legitimate, and important enough to write about. Through publication projects, drawing, drama, and the wide variety of activities teachers can plan, centering student voice is a key factor in reading and writing engagement. For example, when educators place students in the driver’s seat of the drafting, revising, editing, and publishing process, student publication projects support students to both find their voices and to broadcast them. Teachers can invite all student voices by creating classroom spaces with a mix of culturally responsive teaching characteristics such as communicating high expectations for all students, expressing positive perspectives on parents and families, practicing student-centered instruction, and reshaping curriculum to meet all student learning needs. What makes some students more readily able to access and raise their voices is influenced by how the teacher designs a classroom space where students feel free to use their voices.

Student agency

Cultivating in-school literacy experiences that highlight student voice, agency, and influence is in sharp contrast to the drill and kill test prep approach that many teachers feel is necessary to get students to pass the test at the end of the school year. But this is precisely where students need to have their identity, voice, and influence emphasized. Student engagement increases when educators deliberately create a culture that does the following: expects students will give feedback to their teachers about their experiences in class; expects students will share what they want to learn; and expects students will share how they want to learn. The student engagement from this culture occurs when teachers respond to those suggestions by making visible changes to instruction. Specific practices include students performing their writing, conducting research with adult allies, and having forums where student voices, ideas, and lived experiences are prioritized. Authentic or real-world reading and writing tasks increase student engagement. When the audience for writing widens to include people in addition to one teacher, such as letter writing to local politicians, posting poems on classroom walls and stories in school hallways or publishing a class book in which each student authors a piece and reads it aloud during a celebration and book signing ceremony, students experience an increased sense of agency and engagement in the writing process. Student authors connect their writing to a larger purpose, and writing for an authentic audience allows students to gain skills and perspectives that will serve them beyond the classroom. Dynamic and long-lasting engagement comes from the combination of student agency (how do students use their voice to influence their education?), community (how do the people surrounding students influence their perception of school?), and the organizing structures of school (how does student voice influence the structure and organization of the school?). When students choose for themselves, they exercise their own agency, which can increase the strength they feel when attempting to express and act upon their own goals and values.

Student confidence

Confidence is often seen as something that someone either has, or doesn’t have, as if the belief in oneself was a static perception that was either present or not present at birth. However, we know from Carol Dwek’s work on the Growth Mindset that our intelligence and our sense of self evolve over time, and that our self-perception is never at a fixed point. Respected and caring adults in students’ lives have the amazing power to influence students’ perceptions of themselves and others. There are varied ways to build student confidence, including consistent use of authentic writing tasks, reading choice, and repeated reading practices. Increasing student confidence is complex, requiring innovation and persistence from students as they move toward their educational goals, as well as from teachers on behalf of their students. Educators can make choices to provide an array of differentiated reading and writing tasks, integrating student voice and choice into the mix and building their confidence with each new learning opportunity. Required readings, assignments, and projects can be shared at the start of a school year, semester, or unit and teachers can then support students in finding their unique and desired ways to process and express their connections to the reading and writing Valuing a student’s home language and utilizing it as a linguistic tool to problem solve, communicate, and access materials develop students’ literacy skills and self‐confidence. Even in situations where younger students are learning English as a Dual Language, their ability to negotiate the language will have a major impact on their motivation to read and write, or to not read and write. The same can apply to older students who are learning English as a New Language. Whatever the age or nuanced way of referring to learning a new language, when language creates a barrier to entry, students are more likely to give up than they are to keep trying. When students new to learning English can talk with their classmates in their home language, think through complex ideas in their home language, write out their notes in their home language — they’ll have increased confidence in their understanding of the concepts and can, as a separate task, get to work on translating their ideas into English. Success cycles are built when educators better understand how to design their instructional tasks to incorporate opportunities for student voice, agency and confidence.

Download the white paper: Centering Students for Literacy Engagement: Voice, Choice & Identity, A Review of Literature for Behind the Book, conducted by the Center for Professional Education of Teachers at Teachers College, Columbia University.

About Behind the Book

Behind the Book was founded with an instinctive sense that getting kids excited about reading could have a significant impact on their academic (and nonacademic) careers, encouraging depth and freedom of thought, a hunger for knowledge and an understanding and appreciation for worlds beyond the one they know. In the years since Behind the Book began scheduling author visits, programming has expanded and evolved to include art projects, field trips, dramatic activities, the publication of student anthologies and more. About the Center for Professional Education of Teachers (CPET) Sponsored by Teachers College, Columbia University, internationally renowned research university, CPET is a non-profit organization that is committed to making excellent and equitable education accessible worldwide. CPET unites theory and practice to promote transformational change. We design innovative projects, cultivate sustainable partnerships, and conduct research through direct and online services to youth and educators. Grounded in adult learning theories, our six core principles structure our customized approach and expand the capacities of educators around the world.

Low-stakes, high-reward discussion practices you can bring to your math classroom.

Most teachers I know recognize the importance of discussion in their classrooms, but often struggle with how to best facilitate student-to-student discussions, particularly in a content area classroom like math.

As a former elementary educator, I was responsible for teaching all subject areas — Reading, Writing, Math, Science and Social Studies. Math was always my most reluctant subject. When it came time to teach math, I was guilty of sitting in front of the whiteboard, doing practice problem after practice problem with my students, asking if they had any questions, and then sending them off to their desks to do more practice problems in their workbooks. I could tell they were bored (heck, I was bored), but I was unsure how to shift my teaching to make it more engaging and student-centered. I was compelled by the idea that practice makes perfect, right? So the more problems they practice, the more likely they’d be to get it. But the drill and kill approach is not adequate, especially in classrooms today, and as we think about the necessary skills of students in the 21st century. We know they need much more to acquire skills and knowledge that will serve them in real life. They need to be able to talk about math, reflect on their processes, and collaboratively problem-solve.

What is Math Talk?

One of my recent areas of focus and interest is helping math teachers incorporate more discussion in their classrooms and move away from the often well-intentioned chalk and talk approach. “Math Talk,” while a rather new term, is gaining in popularity, as research suggests that when students talk more about their math thinking, they are more motivated to learn and they learn more. It is one of the mathematical practices of the NGS that supports students in clarifying their thinking and understanding, constructing mathematical arguments, developing language to express math ideas, and increasing opportunities to see things from different perspectives. How can teachers promote this challenging yet crucial mathematical practice in their classrooms? What I share below are three simple, yet effective strategies that can promote math talk in meaningful and manageable ways.

Turn and Talks

Turn and talks are a well-known and commonly used strategy. They support oral language, speaking, and listening skills in a low-stakes way. Math can often promote a lot of fear, and fear of getting it wrong. But because students are talking to a partner, there is often less hesitation than if they had to speak to a larger group. Turn and talks can be a great entry point to promoting discussion.

Gallery Walks

Gallery walks are another simple yet meaningful technique to support discussion. These support students in being actively engaged as they walk throughout the classroom, and they can be highly effective in problem-solving within a math classroom. Similar to a turn and talk, a gallery walk could be the focus of the Do Now, as part of guided practice in preparation for independent work, or it can serve as the independent work after some explicit instruction.

Think - Pair - Share

Think-Pair-Share can support students in working together to increase understanding and explore multiple perspectives. Like turn and talks, it is a partner strategy that can be a nice entry point to promoting discussion as its low-stakes and a bit easier for the teacher to manage participation of students. It can be done as part of a Do Now, to review a particular skill, to assess work that is already completed, or as part of independent practice as students apply what they’ve learned.

By no means do I consider myself a math expert; however, I do have extensive experience in promoting discussion in all disciplines. While these strategies are not new or revolutionary, I have witnessed how even small moves can shift instruction to allow for more student interaction and application. I hope you find them helpful as you consider how you can maximize discussion in your classroom, and remember that any of these can be a starting place — as you boost your confidence and experience success, I encourage you to consider your own twists and share them with others.

Three strategies for expanding student engagement in an in-person environment.

Lately I’ve been visiting classrooms and seeing students on their Chromebooks, typing away and answering text-based questions on a Nearpod or on Google Classroom. Teachers are circulating and peering over their students’ shoulders, checking their screens to get a sense of where students are in their classwork, and to ensure they are not sliding between windows to play games or watch videos. At the end of class, teachers sometimes ask students to share a few of their answers, remind them to submit their work, and then class is dismissed. As students are packing up, the teacher may remind students to finish what they didn’t complete for homework.

In a sense, it’s almost as though this type of classroom instruction could have been facilitated in a remote setting. Students are so accustomed to educational apps that they can do their classwork without even attending class. But we are no longer remote, and as far as I can tell today, most schools are not planning to return to a fully remote school program. So how can we make the most of being together in person and increase in-class interactions?

Get students talking

The simplest way to get your students engaged is to include “turn and talks” in your lesson plan, allowing conversations to happen in pairs. Decide on the most strategic moments to include a turn and talk — this could be any time you want students to mull over or think through a key concept during class. Asking students to talk to the person next to them will help them practice their thinking in a low-stakes way. I often find that when just one or two students are participating after a teacher poses a question, it signals that other students are not yet ready to share their thoughts with the rest of the class. Posing a question and asking students to turn and discuss it with the person sitting near them is a way to get students thinking about the key topic, and provides a moment for the teacher to circulate and listen in on students’ thinking. This creates a perfect opportunity to cull new voices in the whole class participation: “What you said, Jess, is a really helpful explanation as to why it can inadvertently hurt our economy. Would you mind sharing this out to the whole group when we come back together?”

Make thinking visible

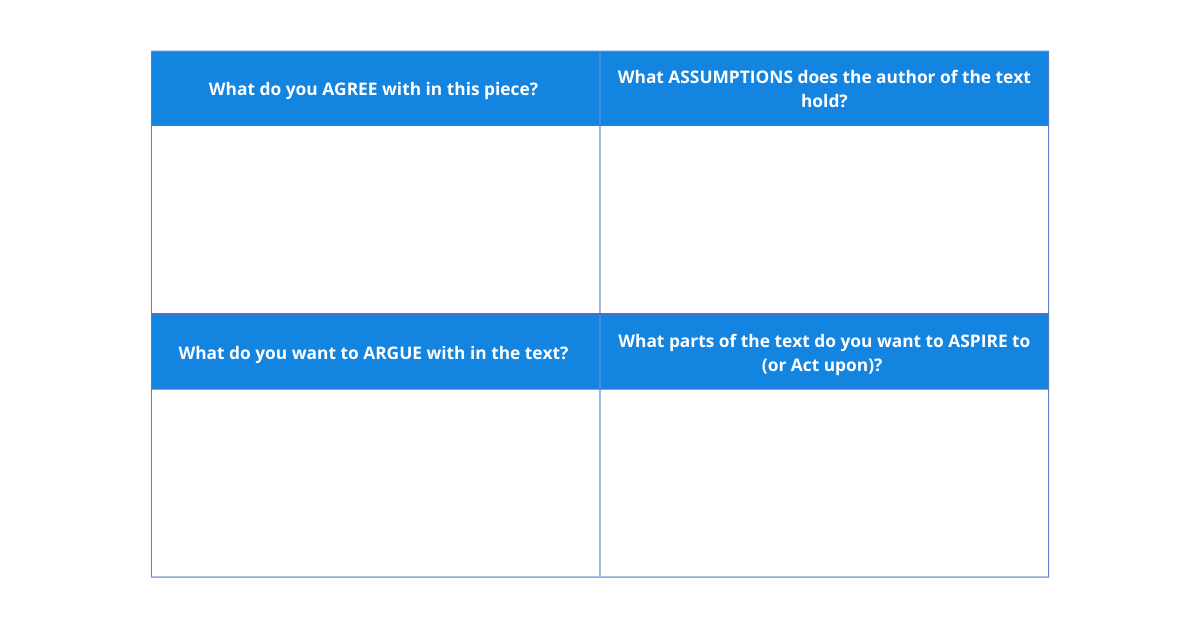

Pull out some chart paper and ask students to share their thinking in groups and on paper. Working on Google Docs as a group can be useful for co-writing or sharing ideas, but working on chart paper is a more strategic way to share thinking within a group and to help make the thinking visual. Some graphic organizers lend themselves well to chart paper, particularly when students are using a graphic organizer to process a concept. For example, the 4 As Protocol works well on chart paper. My colleague Courtney Brown and I have often used this protocol on chart paper as a way to demonstrate thinking about a text through these specific lenses, which can look like this:

Bring voices to the whole class

If you were a real rookie on Zoom during the pandemic (like me) and tried to have a full class discussion (like me), you quickly longed for the days to return to in-person instruction. I wince when I recall the first time I asked students to discuss what we had read — there were moments of everyone talking over each other, or everyone muted and awkward silence. While I had asked students to collect their thoughts in writing as the primary step to having a discussion, I could not ask students to turn and talk casually for 45 seconds. I could have created breakout rooms for a minute or two, but somehow breakout rooms seem too formal. Now that we are in class together, let’s take the opportunity to help our students learn how to have a discussion as a whole group. Work up to a larger discussion by building small steps along the way: first a quick write on the topic, then a turn and talk, and finally, opening up the chance for students to share with the whole class. Using a discussion rubric in live time and then reflecting on the discussion is another way to remind students what makes for an effective conversant.

During the pandemic, we were flexible and experimented with different online learning tools. We discovered ways to teach and assess students, and we did the best we could during a most difficult time. But now that we have returned in person, let’s take advantage of being together and find ways to use the lessons we’ve learned during remote learning to increase interactions in our in-person classrooms.

Capitalize on critical thinking, reflection, and action to keep your students actively engaged.

“It’s so hard for me to come up with something to do every day in my class. I know my lessons should prepare students for their summative assessment, but, like, what do I do every day? Every class?”

This was how my meeting began with a relatively new teacher I am mentoring. He knows where he needs to end up in his unit, but what can he do in every single class that doesn’t feel monotonous? What various activities can he use in his class that work towards a concept he is building? In his case, his summative assessment will be an analysis of a theme in the class novel, but he also aims to use the text to teach other concepts, other literacy skills. Enter our student engagement resource (download here). It’s so easy to get stuck doing the same activities each day. Using this resource, you can unlock practical ideas for engaging students cognitively, and find ways to spur students to think about the class text or class concepts from multiple perspectives. I particularly appreciate how these activities are easily adaptable, and can be rooted in concepts students are learning. Across four categories, you can imagine fresh lesson ideas, no matter where you're at in your career.

GET STUDENTS...

Thinking Quote-ables: Pull meaningful quotes from student writing or discussions, and post them around the room. This activity is a way to synthesize students’ ideas, reflections, and wonderings around a topic, and the result is that student voice becomes a new collaborative text. When students see meaningful snippets of their own writing on chart papers around the classroom walls, they will feel seen. A wonderful add-on to this could be to ask students to respond to others’ writing using post-it notes or directly on the chart paper itself. This activity reinforces ideas discussed in class, celebrates student voice, and helps students see concepts through their classmates’ perspectives.

GET STUDENTS...

Doing Get centered: Create student choice by organizing 2-3 different activities around a text (vocab, drawing, summarizing). Allow students to choose which center they want to focus on. Creating a “centers” lesson is a way to get students up and out of their seats to focus on a topic of study using various manipulatives. A variation of this is to create “stations” where students rotate between the stations (or center). Station or center lessons require quite a bit of planning in order to create independent activities that are allotted a similar timeframe, but a “centers” lesson ensures students are actively engaged, and teachers are observing and providing support when needed.

GET STUDENTS...