|

Envision how you can cultivate clear communication and cohesive leadership across your community.

Building a cohesive community in large public schools, often with over 2,500 students and 200 staff members, presents unique challenges. Fragmented communication and a lack of understanding of roles can hinder unity and the effective implementation of initiatives. However, leveraging the leadership team to clarify roles, expectations, and prioritize students at the center can foster a stronger community.

How can we do this? What might it look like? Case study: navigating change & complexity

In my eight years working with a large public school in Georgia, I've seen firsthand the difficulties in maintaining cohesion amidst frequent changes in administration, leadership, and student demographics. Despite well-intentioned systems and structures, the key issue often lies in the communication and understanding of expectations across the school.

For example, at the start of the school year, a new administrator joined the team, and introduced a new unit planning template aimed at enhancing differentiation for ELL and SPED students and using data to improve instruction. However, teachers were frustrated by the lack of clarity and timing of the rollout. It wasn't the plan itself, but rather the manner and timing of its introduction — amid numerous other mandates — that caused frustration. As a result, I worked with the teachers over the course of a day in late August, to unpack and make sense of the unit plan and how it could support them in facilitating their professional learning communities and use data to inform instruction. Furthermore, the departure of three seasoned instructional coaches led to the formation of essentially a new team, underscoring the necessity for community-building and standardizing approaches. Thus, on the second day of my visit in August, I collaborated with the coaches to articulate the team's mission and vision, and to devise coaching plans to address specific departmental goals and challenges. This collaborative effort aimed to empower the coaches by instilling in them a sense of purpose and providing clear direction. As I concluded these two days, I felt a sense of achievement, armed with a well-defined plan and next steps. Addressing confusion: building a unified front

Upon returning in February, however, I encountered more changes and more confusion. A new instructional coach had been added to the team, requiring onboarding and community building. Additionally, a coach expressed uncertainty after participating in a co-teaching session with one of her teachers, recognizing its potential as a powerful support model, but questioning whether it fit within the scope of her role. And another coach wanted to restructure PLCs but was uncertain of administrative approval. This confusion showcased a disconnect between administration, coaches, and teachers.

Leadership retreat: a strategic approach

What became apparent to me was the need to strengthen communication and understanding across the school. The lead instructional coach — a seasoned and reliable figure within the school — and I collaborated to reach out to the principal. Together, we arranged a leadership retreat with the aim of addressing these challenges.

We worked side by side in planning the retreat, focusing on the following objectives: 1. Engaging key stakeholders Based on my conversations with teachers and teacher leaders, there was an overwhelming number of meetings taking place, many of which felt unnecessary and unproductive. This also contributed to confusion as the information trickled down from person to person, risking various interpretations and varying implementations. We wanted to reduce this risk by ensuring essential stakeholders — principal, APs, instructional coaches, and department chairs — were present at the retreat, to share perspectives and make informed decisions. 2. Building community and fostering relationships Large schools make it harder to feel connected across the larger number of teachers and leaders. The retreat was intended to be an opportunity for leaders to connect personally and professionally, fostering trust and shared responsibility. 3. Establishing priorities It became clear to me that the principal and his cabinet knew what the goals of the school were, but not so much the other leaders across the school. The retreat aimed to establish clear goals and priorities, ensuring alignment across the school leadership. 4. Clarifying roles and responsibilities Based on different conversations I was having at different times, it became clear that there was confusion around roles and responsibilities. Reflecting on and understanding each leader's role helps reduce confusion and aligned efforts. For the retreat, we wanted to focus on questions like: How do I understand my role? Does this align with my desires/hopes for this role? How does my role compare, support, and/or overlap with others in the school community? 5. Planning for the future One of the pitfalls schools face is too many priorities and initiatives, which can result in feelings of failure and overwhelm. This was the case at this school. We wanted leaders to work on and ideally establish the school calendar together to ensure there was enough time and space for these initiatives to thrive in the subsequent school year. We wanted to ask questions like: What do we need to plan for now to implement successfully in the coming school year? Who is responsible for these various initiatives and how will we monitor progress? I just recently debriefed the retreat with the lead coach. Overall, she believed the retreat was a success, leaving participants with a clearer sense of purpose and responsibility. Additionally, she believed it strengthened relationships and understanding of day-to-day roles. Promising practices for all schools: a blueprint for success

Although this article centers on a single school, it highlights several promising practices that can benefit schools of any size. I see the potential for these strategies to be valuable for any organization and its leaders.

By adopting these practices, schools can enhance connection, understanding, and ultimately support the most important goal of all — advancing our students.

How one school's teacher leaders are cultivating curiosity and creating a roadmap for meaningful change.

In a recent professional development session at a high school in Georgia, I aimed to enhance a group of leaders' understanding and use of inquiry in their practice. Guiding teacher leaders through an exploration, I encouraged them to reflect on the everyday significance of inquiry within their professional roles, emphasizing its promise in driving practical growth and development. Together, we engaged in a reflective dialogue that included delving into the process of inquiry, unpacking its intended purpose, and highlighting its importance in fostering a culture of continuous improvement within the school community.

The importance of inquiry

What exactly is inquiry, and how does it enhance the work of teacher leaders? Inquiry, simply put, involves deepening understanding through curiosity, questioning, and seeking answers, supported by data analysis. It serves as a means for collaborative exploration, enabling educators to address shared challenges, develop effective strategies informed by data insights, and monitor progress towards common goals. Through this process, teacher leaders not only enhance their own practice, but also foster a culture of evidence-based decision-making within their school communities.

Central to this exploration are inquiry teams, which consist of professionals coming together in their quest for understanding and improvement. These teams operate based on the principle of intentional collaboration, prioritizing issues relevant to their roles and responsibilities. This approach ensures that inquiry projects remain manageable and grounded, enabling teams to achieve tangible outcomes. Moreover, it cultivates a culture of shared responsibility and commitment, fostering an environment that promotes collective growth and progress. Navigating the stages of inquiry

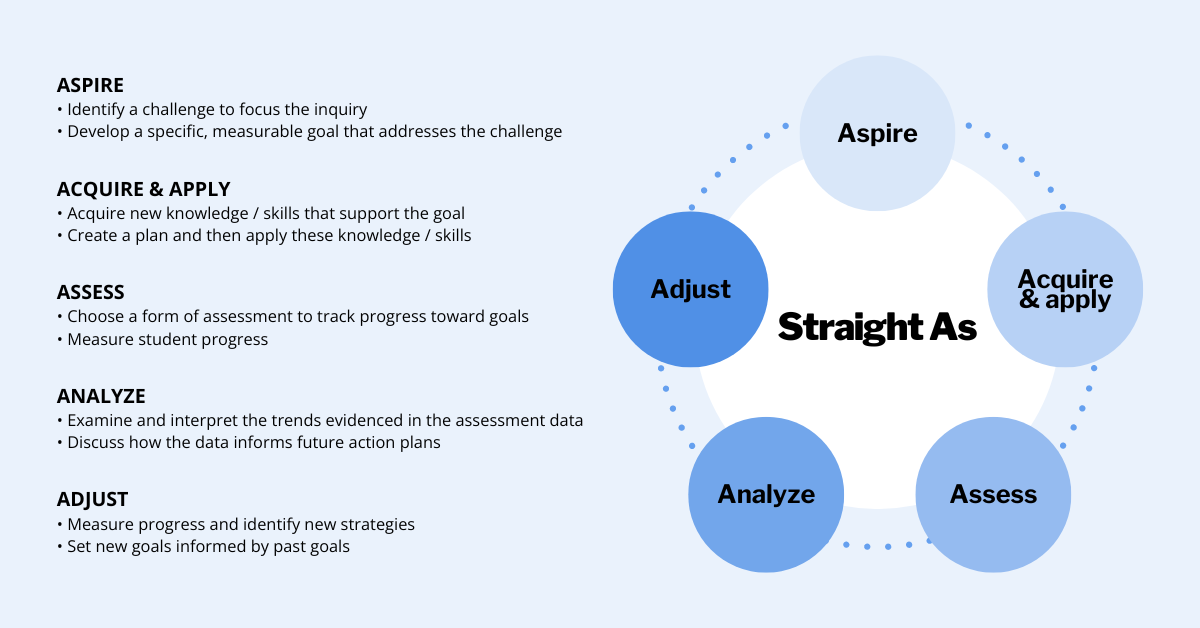

One notable framework that supports inquiry with teacher leadership is our Straight As protocol. This serves as a structured approach for navigating the stages of inquiry, guiding educators through a systematic process of goal setting, knowledge acquisition, assessment, analysis, and adjustment.

Our initial session in Georgia was focused on the Aspire stage, where teacher leaders chose to explore the challenges faced by their students and collaboratively identify SMART goals — goals that are specific, measurable, actionable, relevant, and timely. Teachers identified challenges such as stamina, confidence, literacy, Lexile levels, and more. From there, we analyzed these challenges and attempted to narrow down our list by thinking about which obstacles could be combined, as well as which obstacle(s) felt the most important, the most urgent, or were in a high-leverage area. Through a process of reflection and dialogue, each department gained a clear understanding of their objectives and a roadmap for achieving them.

During our time together, we thoroughly analyzed various SMART goal examples, focusing on key aspects, such as:

We also examined sample inquiry questions, proposed change strategies, and the anticipated timelines. This comprehensive approach aimed to equip teacher leaders with the necessary insights and tools to effectively formulate their own goals. At the end of the day, each department presented their SMART goals for feedback, fostering collaboration and refinement. As a next step, our group of teacher leaders will present these goals to their respective department teams with the hopes of further refinement and integration into a larger inquiry process throughout the semester as we continue our work together.

The process of inquiry provides teacher leaders with a practical approach to deepen their understanding, collaborate effectively, and drive meaningful change within their school communities. By embracing the principles of inquiry and utilizing frameworks like the Straight As protocol, educators can see themselves as catalysts for positive change, enhancing their teaching practices and empowering their students. Moreover, by incorporating data analysis into the inquiry process, educators can make informed decisions based on evidence, thereby increasing the effectiveness of their strategies and interventions.

Turn the obstacles created by shifting learning styles into opportunities for adaptation and innovation.

When it comes to education, every era has its defining tools and methods, each playing a central role. From the iconic chalkboards that once graced classroom walls to the overhead projectors that illuminated our lessons, these tools were fundamental in shaping our educational approaches. However, as technology continues to progress, these traditional tools are gradually being replaced by more advanced alternatives.

As such, education must evolve to keep pace with these changes, and teachers need to adapt to new technologies and teaching methods to effectively meet the needs of their modern learners. In a world defined by 21st century innovation, we can no longer rely on 20th century teaching methods. Yet, embracing change is no easy feat! In a whirlwind of shifts, resistance often arises, especially from educators who’ve experienced firsthand the loss and excitement of these transitions. Many educators find themselves grappling with the need to let go of cherished beliefs and teaching methods rooted in their own experiences and identities. In my recent conversations with teachers, a common sentiment emerges: the perceived disinterest of students in reading, their struggle with mastering basic skills like multiplication tables, and their apparent lack of engagement in critical thinking. These concerns are undoubtedly valid. However, as educators, we must confront the reality that today's students interact with reading, interests, and motivations in ways vastly different from previous generations. Accepting these changes can be difficult, especially when they seem to highlight deficiencies. But if we examine the changes and evolutions of trusted teaching methods of the past, we can gain insight into how technology continues to shape our ways of living and learning, setting the stage for understanding which teaching methods have become obsolete in today's digital age. The textbook

Modern textbooks became a staple starting in the 15th century. These trusty learning companions were used by teachers and students for generations and were praised for their wealth of knowledge evident in their heavy weight. Carrying a textbook was once a symbol of academic dedication, but in today's digital world, textbooks alone do not suffice. They're too basic for modern learners who want interactive, multimedia experiences, and as technology advances and access to information increases, textbooks just can't keep up with the engaging and personalized learning experiences students need.

The encyclopedia

In the 16th century, the encyclopedia was introduced. It was once praised as the most powerful source of human knowledge, jammed between two hardbound covers. I remember being fascinated by Encyclopædia Britannica and waiting in line to use the limited supply in our classroom. I would turn the delicate pages to find answers to all sorts of questions. But today, hard copy encyclopedias are obsolete. Students now have access to the vastness of the internet for instant information and real-time updates.

Library catalog systems

In the 19th century, we experienced the creation of the modern library catalog system, with its neatly indexed cards and Dewey Decimal classifications. It was once the key to the world of knowledge within a library's walls — it guided students through the maze of shelves, leading them to the books and resources they wanted to read. I distinctly recall my visits to the library, armed with my own shiny library card, seeking advice and assistance from the librarian, and paying fees when I missed the return deadline.

Yet, with the advent of digital databases and online search engines, the catalog system is a symbol of the past, replaced by instant access to a wealth of information at our fingertips. Furthermore, the act of reading itself has undergone a significant transformation. While some still cherish the smell and feel of a physical book, like me, checking out physical books has become a distant memory for many. Many people have embraced the convenience of accessing articles, podcasts, audiobooks, and other digital formats. The act of "reading" has expanded to include a wide array of mediums, reflecting the changing preferences and lifestyles of readers and learners in the digital age. The only constant is change

These transformations reflect the resilience of education in the face of technological advancements, underscoring that with change comes the potential for growth, adaptation, and progress. Librarians have evolved into “digital resource coordinators,” “media specialists,” and “information specialists,” guiding learners through the digital landscape. And traditional book companies have transitioned to online platforms for greater accessibility and customization.

Today, we're facing rapid technological changes, like YouTube, TikTok, and social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. There's also a growing presence of Generative AI, which, like changes in the past, can feel daunting. These advancements are reshaping the learning landscape, with some fearful of the implications for originality and personal privacy, while others view them as an opportunity to revolutionize education by offering personalized learning experiences for every student. The importance of reflection for innovation

I've been encouraging teachers to ask: What are the goals I have for my students? Where do these goals originate, and do they align with the demands of the 21st century? These inquiries prompt us to determine when adjustments are necessary, whether it involves letting go of outdated methods, revising our approaches, or affirming current practices.

Recently, I've observed educators designing innovative and relevant projects that deeply engage their students. These projects often culminate in products inspired by social media or TikTok videos, and sometimes incorporate QR codes for added interaction. For example, in a history class, students were creating short TikTok-inspired videos depicting key historical events or figures, using creative props and costumes to make the content engaging and memorable. These challenges can encourage active learning and collaboration among students, as they work together to brainstorm ideas and produce their videos. In a science class, I witnessed students engaging in a "Science Experiment Challenge" where they were tasked with filming themselves, with help from the technology teachers, conducting simple experiments and explaining the scientific principles behind them. This not only reinforces learning but also allows students to showcase their understanding in a fun and interactive way. In an art class, a teacher had her students showcase their creative projects by creating a series of Instagram- inspired posts including captions and comments, allowing them to document their artistic process from conception to completion. And in an ELA class, a teacher shared how she has been using AI platforms, like Brainly, to provide additional support to her students by offering personalized tutoring sessions, answering questions, and providing explanations on various topics, supplementing traditional classroom instruction. These examples demonstrate teachers’ efforts to stay updated on technological changes and connect with students by leveraging their interests.

Regardless of your sentiments around these shifts and changes, their impact on students cannot be denied. Therefore, it's crucial to shift our focus towards supporting students in developing the skills and competencies necessary for success in the modern world. Rather than viewing students' changing learning styles and interests as obstacles, we must see them as opportunities for growth, adaptation, and innovation.

By meeting students where they are and embracing their unique perspectives, we can foster a learning environment that encourages curiosity, critical thinking, and engagement with the world around them. This approach not only prepares students for the challenges of today, but also equips them with the resilience and adaptability needed to thrive in an ever-changing future.

References

The Journal of American History Textbooks Today and Tomorrow: A Conversation about History, Pedagogy, and Economics Encyclopedia Britannica

Empower students to assess their own learning and take charge of their educational experiences.

One of the most exciting things about project-based learning is that it lets students take control of their learning experience, allowing them to lead their educational journey. However, understanding what this truly means and visualizing what it might look like in practice can sometimes feel unclear and ambiguous.

For me, the above means fostering student discovery and embarking on a shared journey with students to achieve specific goals. One way I support teachers with this approach is through collaboratively establishing success criteria with students, rather than dictating them. Moss and Brookhart (2015) advocate for this process, emphasizing the importance of ensuring that students comprehend the learning goals and have a clear understanding of what exemplary work on a project looks like. This ongoing process involves teachers regularly monitoring and assessing students' understanding of learning goals and addressing any misconceptions that may arise.

Empowering student discovery

The significance of success criteria lies in empowering students to assess their own learning and take charge of their educational experiences, fostering a sense of self-efficacy. Students who believe in their ability to succeed are more likely to persist in their work, even in the face of challenges (Bandura, 1997). In essence, success criteria become a means to provide students with an opportunity to actively drive their own learning. Teachers play a significant role in this process by posing essential questions such as: What do I want my students to learn? How will I teach it? How will I know they got it? Similarly, students are encouraged to inquire about their own learning: What will I learn? How will I learn it? How will I know that I got it? When it comes to communicating success criteria, we can tell students explicitly, show them through modeling, offer examples, or support them in discovering the criteria themselves, whereby students are actively exploring, uncovering, and understanding concepts or knowledge on their own. Student discovery leads to deeper understanding, greater intrinsic motivation, longer retention of knowledge and skills, as well as promoting student ownership over their learning. To facilitate this discovery, I want to share four promising practices.

Promising Practice: Questioning

Engage students in questioning to ensure a deep understanding of project goals. Techniques such as putting learning targets in their own words, Think-Pair-Share, and an iteration of KWL (what we know, want to know, what we will need, what learning/skills we can lean on) can be effective. An example of series of teacher-facilitated questions as part of a project on the water cycle could sound like:

Promising Practice: Envisioning

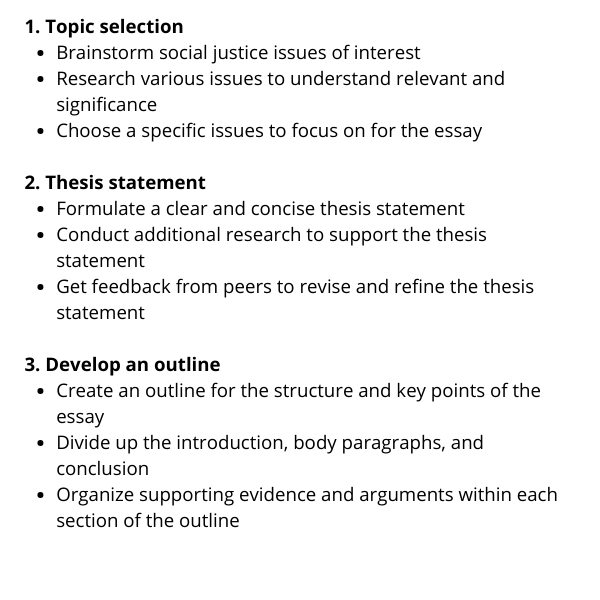

Support students in visualizing their goals and the final project outcome. Creating planning charts, breaking down tasks into smaller parts, and involving teachers in the planning process can enhance students' understanding and success. Here is an example of a student-created planning chart for a high school social justice project:

Promising Practice: Using exemplars

Expose students to examples of past work, encouraging them to analyze and describe its traits, features, and styles. This inductive approach allows students to discover project expectations through inquiry and exploration, promoting a deeper understanding. This could look like:

Promising Practice: Rubrics

Utilize rubrics not just for evaluation, but as a guiding tool throughout the project. Students can assess examples, rephrase or recreate rubrics in their own words, and use them to evaluate their own work and that of their peers, informing revisions. An example of this could look like:

The journey toward student-driven project-based learning is marked by the collaborative establishment of success criteria, enabling students to actively participate in their own learning. By implementing these promising practices, educators can create an environment where students not only understand the goals, but also take ownership of their educational path, ultimately promoting continuous growth and exploration.

Creativity flourishes in an environment where exploration is encouraged and individual voices are celebrated.

Genre-based writing is the art of crafting narratives within distinct literary genres or categories. Literary genres, such as fiction, non-fiction, poetry, drama, science fiction, fantasy, mystery, and romance, are defined by specific stylistic elements, forms, and content.

Engaging in genre-based writing involves intentionally aligning one's writing with the conventions, themes, and structures associated with a chosen genre. This process includes utilizing storytelling techniques, incorporating stylistic elements, and exploring themes relevant to the selected genre. For instance, a mystery novel might feature a central crime, a detective, and a resolution, while a romance novel centers around a key romantic relationship within the plot.

Why genre-based writing matters: a deeper exploration

Recognizing the significance of genre-based writing goes beyond the conventional understanding of major genres such as narrative, argumentative, and informative. It involves delving into the unique sub-genres, including speculative memoirs, flash fiction, Ted Talks, infographics, Op-Eds, and more. This exploration involves immersing oneself in an inquiry-based study of specific texts, a process that reveals nuances that often transcend traditional genre boundaries. Within this exploration, the promotion of creativity takes center stage. By encouraging students to engage with diverse sub-genres, teachers foster an environment where creativity can flourish. This approach not only sets clear expectations for writers, but also enhances their ability to communicate effectively with their audience. In doing so, it allows readers the freedom to choose works that are tailored to their preferences, fostering a deeper connection and appreciation for the art of writing. The Student Press Initiative (SPI), a signature initiative at CPET, strongly advocates for genre-based writing as a meaningful framework that not only expands literary possibilities, but also nurtures the creative spirit within each student.

What does genre-based writing entail?

SPI serves as a guiding force for both teachers and students in the realm of genre studies, employing a close examination of exemplars — often drawn from a diverse array of published texts, ranging from poems and essays to PSAs. In this process, students engage in a detailed analysis of these texts, examining content, structure, and craft through the lens of a writer, taking in all of its attributes and conventions in the process. The collaborative nature of this exploration lays the groundwork for creativity. Through shared discussions and the creation of charts, students collectively share insights into the genre and its unique characteristics. Rather than prescribing what or how to write, teachers adopt an empowering stance, encouraging students to explore and discover, thereby nurturing the development of insightful ideas and observations. This student-driven approach not only empowers individuals but also transforms the teacher's role from knower, to that of a facilitator or provocateur, cultivating a powerful space for exploration, self-discovery, and creativity. In a recent workshop I facilitated, SPI coaches immersed themselves in a genre-based study of the poem "What For" by Garret Hongo. While I’ve used this poem many times on many different occasions, I’m always impressed by the new ideas, observations, and questions that arise, underscoring how readers engage uniquely with texts. Collective discussions delved into content, form, and structure, highlighting original stylistic moves by the author. For instance, one coach noted changes in stanza lengths, sparking a discussion on its intentional contribution to the poem's meaning. Another coach made note of his powerful auditory imagery, and another made content connections to the American Dream. This exploration set the stage for coaches to embark on their own creative journeys, crafting "What For" poems inspired by Hongo's content, form, and craft, including elements such as repetition and reiterated structures. Reflecting on the similarities and differences among these poems further deepened the collective understanding of this specific genre, demonstrating how creativity flourishes in an environment where exploration is encouraged and individual voices are celebrated.

Unleashing creativity and self-discovery

In summary, genre-based writing is a powerful tool for creativity, independent thinking, and self-discovery. Embracing this approach turns educators and students into skilled explorers of various literary genres, creating a collaborative and empowering learning space.

Support emerging readers' vocabulary with a balance of explicit instruction and in-context learning.

This is the fifth installment in our Science of Reading series

Vocabulary is a crucial component of reading comprehension and literacy development. Understanding vocabulary and its significance is essential for educators as they work to support emerging readers on their journey to becoming skilled and proficient readers. In this fifth and final installment focused on the science of reading, we will unpack what vocabulary means, why it is important, and provide three promising practices that teachers can implement to effectively support emerging readers with vocabulary development.

What is vocabulary in the science of reading?

In the science of reading, vocabulary refers to the collection of words that a reader understands, recognizes, and can use effectively in their reading and writing. It encompasses both oral vocabulary (words we understand and use in speaking) and print vocabulary (words we recognize and understand in reading). Vocabulary development is a multifaceted process that involves word learning, comprehension, and retention.

Why is vocabulary development important?

Vocabulary serves as the anchor connecting various critical reading skills, fostering a deeper understanding of phonological awareness, phonics, and fluency. In phonological awareness, it enhances recognition and discernment of sounds within words, ultimately aiding in the decoding and pronunciation processes. When it comes to phonics, a robust vocabulary equips learners with the ability to detect word structures and pronunciation nuances, enabling them to effectively apply phonics rules during reading. Additionally, vocabulary ensures swift and accurate word recognition, which significantly contributes to reading speed and fluency. But perhaps most importantly, vocabulary enhances reading comprehension by giving readers the capability not only to recognize words, but also to understand their meanings within a text. Without a strong vocabulary, readers will likely encounter difficulties in grasping the core of what they are reading, ultimately hindering overall comprehension.

Promising practices for vocabulary development

Plenty of vocabulary strategies exist, but issues arise when one approach is excessively emphasized or prioritized, potentially leading to minimal or even neglected use of others. For example, overreliance on explicit vocabulary instruction may lead to isolated word memorization without a deeper understanding of word usage in context. An effective approach strikes a balance between explicit instruction and in-context learning. Below, I present three promising practices, as well as concrete examples of how I implemented these practices in my classroom. I believe these examples encompass various methods for explicitly supporting young readers' vocabulary development. Ideally, teachers will utilize all three practices, at different times, to create a comprehensive and holistic approach to vocabulary instruction.

Vocabulary development is a fundamental aspect of reading and literacy. In the science of reading, understanding what vocabulary is and why it's important is crucial for educators. By implementing explicit vocabulary instruction, contextual learning, and engaging word play and games, teachers can provide effective support for emerging readers, helping them build a strong foundation for successful, lifelong reading.

Incorporate active comprehension strategies that allow students to deeply engage with the texts they encounter.

This is the fourth installment in our Science of Reading series

Throughout our science of reading series, we've been exploring the crucial aspects of reading proficiency. In this installment, we will delve into reading comprehension, a fundamental skill that transcends the mere decoding of words on a page. Comprehension involves understanding, interpreting, and making meaning from the text. This ability is essential for success because it enables readers to connect prior knowledge with new information, make inferences, identify main ideas, and draw conclusions.

In the context of the science of reading, which emphasizes evidence-based reading instruction, reading comprehension holds a critical position. It recognizes that reading is not a single skill, but rather a complex interplay of various cognitive processes. Furthermore, it acknowledges that reading comprehension is built upon a solid foundation of phonological awareness, phonics, and fluency, as discussed in our previous articles. These foundational skills are essential for developing proficient readers, as they provide the necessary groundwork for understanding the content of the text. Now, let's delve into the significance of incorporating comprehension strategies alongside fluency and phonics, highlighting how they enhance the reading experience for students.

The power of active reading comprehension strategies

While fluency and phonics lay the foundation for reading proficiency, active comprehension strategies are the key to unlocking the true potential of these foundational skills. Fostering deeper understanding: Comprehension strategies encourage students to dive deeper into the text. When they actively make predictions, ask questions, visualize scenes, or summarize key points, they engage with the material at a greater level. This not only aids in grasping the surface level content, but also enables them to explore underlying themes, character motivations, and the author's intent. Bridging gaps in proficiency: Active comprehension strategies bridge the gap between students who excel in fluency and decoding, and those who struggle. For those proficient in these areas, comprehension strategies provide the tools to dig deeper and extract more meaning from texts. Meanwhile, students who may struggle with decoding and fluency can still make powerful inferences and predictions when they engage with comprehension strategies. This inclusivity ensures that no student is left behind in their reading journey. Promoting critical thinking: Comprehension strategies encourage students to analyze information, draw connections, and evaluate the significance of details within a text. This not only enhances their comprehension, but also equips them with valuable life skills that extend beyond the classroom. Building lifelong readers: The integration of comprehension strategies nurtures a love for reading. When students actively engage with texts, they become more invested in the reading experience. This can lead to a lifelong passion for reading and learning, setting the stage for continued growth and success.

Effective strategies for promoting comprehension

Incorporating comprehension strategies alongside fluency and phonics is essential for developing well-rounded readers. Below are three strategies I found to be particularly helpful for supporting comprehension in my young readers.

Explicit comprehension instruction

One way to promote comprehension is to provide explicit instruction of evidence-based strategies, such as making predictions, asking questions, visualizing, summarizing, and making connections while reading. Encourage readers to actively engage with the text by discussing their thoughts and insights. Model these strategies and provide ample opportunities for guided practice. By equipping students with these tools, you empower them to extract deeper meaning from the text. When I was in the classroom, I leaned on pre-, during-, and post-reading strategies and exercises that were focused on the asking of questions. By teaching my students to ask questions about the story, I helped them become active readers who think deeply about what they're reading and develop a better understanding of the text. An example lesson might look like:

Vocabulary development

A robust vocabulary is crucial for comprehension, as it bridges decoding skills like phonics and the ability to understand and enjoy texts fully. When students encounter unfamiliar words while reading, a well-developed vocabulary allows them to unlock the meanings of these words, making the reading experience more enjoyable and meaningful.

By integrating vocabulary instruction into reading lessons with a focus on context clues, students not only enhance their comprehension skills, but also strengthen their phonics abilities by recognizing and deciphering unfamiliar words within the context of the text. This holistic approach ensures that students not only decode words accurately, but also understand them in the broader context of the story. Building a strong vocabulary enhances comprehension by enabling students to grasp the nuances and subtleties of language.

Independent reading

In my classroom, I embraced the power of independent reading as a key component of our literacy program. Independent reading, also known as "personalized reading time," was a daily activity where my students had the freedom to choose books or materials that both matched their reading levels and piqued their interests. Studies have found that when students are allowed to choose their own reading materials, they are more engaged and invested in the reading process, resulting in improved comprehension (Guthrie and Humenick (2004)). To support independent reading, I ensured our classroom library was stocked with a wide range of books and magazines. This diversity catered to different reading levels, genres, and topics, giving each student ample choices. During independent reading time, students had the autonomy to select their reading materials, which fostered a sense of ownership over their reading experience, making it more engaging and enjoyable. I worked closely with each student, mostly through conferencing, to ensure they selected books that matched their reading levels. This ensured that the material was neither too easy nor too challenging, promoting comprehension and confidence. To enhance comprehension and encourage reflection, I periodically organized book discussions or "book talks." If multiple students were reading the same book, we would gather for a group discussion. In these sessions, students had the opportunity to share their thoughts, insights, and favorite parts of the book. It promoted a sense of community and enthusiasm for reading. After each independent reading session, I encouraged students to reflect on what they had read and set personal reading goals. This reflection helped them track their progress and set targets for improvement. Lastly, students kept reading journals where they recorded the titles of the books they read, brief summaries, and personal reflections. These journals served as a valuable tool for tracking their reading journey. By incorporating independent reading into our daily routine, my students not only improved their reading comprehension, but also developed a genuine love for reading. It was a practice that empowered them to explore diverse texts, share their reading experiences, and become lifelong readers.

Elevating comprehension

By integrating explicit comprehension instruction, vocabulary development, and independent reading, educators can establish a holistic approach to literacy that extends beyond fluency and phonics. This approach ensures that students not only read accurately, but also engage deeply with, analyze, and appreciate the texts they encounter, equipping them with the full range of skills essential for reading development and proficiency.

Nurture confident readers by blending phonics into the fabric of your literacy instruction.

This is the third installment in our Science of Reading series

When it comes to early reading instruction, few topics have sparked as much debate and controversy as the teaching of phonics. Over the years, the pendulum has swung between extremes: some advocate for phonics as the exclusive focus of instruction, while others argue for its complete exclusion from the curriculum. However, the crux of effective literacy education lies in finding a harmonious balance. As part of my series dedicated to unraveling the science of reading and nurturing young readers, we embark on a journey into the world of phonics. What exactly is phonics, what role does it play in reading development, and how can early childhood educators incorporate it into their classrooms through a balanced approach?

Defining Phonics: The Foundation of Reading

At its core, phonics is the relationship between the sounds of spoken language and the letters that represent those sounds in written language. It's the code that unlocks reading comprehension. Phonics instruction involves teaching students how to connect the sounds of spoken language (phonemes) to the symbols (letters or letter combinations) that represent them (graphemes). We dig deeper into this topic in my previous article, which examines how to nurture phonological awareness in emerging readers. Phonics equips young readers with the skills needed to decode words — without phonics, the process of learning to read would be like trying to solve a complex puzzle without understanding the individual pieces.

The Purpose and Importance of Phonics

Phonics serves several crucial purposes in the development of young readers: Decoding Words: Phonics provides the key to unlocking unfamiliar words in texts. When students understand the relationships between sounds and letters, they can sound out words they haven't encountered before. Building Fluency: Proficiency in phonics helps build reading fluency. Fluent readers can read with accuracy, speed, and expression, which enhances comprehension, as we have discussed in previous articles. Spelling Proficiency: Phonics instruction also contributes to spelling skills. When students know the sounds associated with letters and letter combinations, they can spell words more accurately.

Balancing Act: The Key to Phonics Success

A balanced approach to phonics instruction is essential in literacy education for several reasons. Firstly, it facilitates a well-rounded development of essential reading and writing skills, encompassing phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, and writing proficiency. This holistic perspective acknowledges and embraces the diversity of learners, accommodating various learning styles and individual needs. The integration of phonics within authentic reading and writing contexts is a critical aspect of this approach. By immersing students in real-world applications of phonics skills, it not only reinforces learning, but also enhances reading fluency. This equips students with a range of word recognition strategies, lessening their reliance solely on phonics, and thereby improving reading efficiency. Furthermore, a balanced approach recognizes that the ultimate goal of reading is comprehension. It weaves phonics instruction together with comprehension strategies, ensuring that students not only decode words, but also understand and interpret the text they read. Creating a balanced approach to instruction can offer essential support for struggling readers, tailoring instruction to meet their specific needs and providing a scaffold for their literacy development. Ultimately, it fosters a deep appreciation for literacy, nurturing lifelong reading and writing habits, and in doing so, it aligns with evidence-based practices in literacy education.

A Balanced Approach In Action

As a third-grade teacher, I often recognized the need to teach phonics to specific groups of students, even though it wasn't a part of the standard curriculum. One approach I used was phonics through literature, where I selected books featuring specific phonics patterns, and integrated phonics instruction within shared reading sessions. For example, if I wanted to focus on the long a sound spelled with the silent e pattern (e.g., "cake," "gate”), I could use a book like Jake Bakes Cakes, which prominently features words with this pattern. I would then use this text to engage in a shared reading session, where I read the book aloud to the class, pausing at words with the target phonics pattern. For instance, when we encountered the word cake, I might emphasize the long a sound and point out the silent e at the end of the word. After reading, I would engage the students in a discussion about the phonics pattern, asking questions like, "What sound does the e make at the end of the word cake?" or "Can you find other words in the story with the same pattern?" To support word recognition, I would encourage students to identify and read words with the target pattern in the book. They might take turns reading sentences or identifying words on specific pages. I would also have students use magnetic letters or word cards to demonstrate how changing the vowel sound (e.g. cake to make) affects the word's pronunciation and meaning. Students would then manipulate letters to create new words following the same pattern. If there was time, I would also ask students to engage in word play activities related to the phonics pattern, such as creating rhyming words or making word family charts, to reinforce the concept. As a follow-up activity, students might be encouraged to write their own sentences or short stories using words with the target phonics pattern. The key idea behind phonics through literature is that phonics instruction is embedded within the context of enjoyable and meaningful texts, fostering a love for reading and connecting phonics to authentic language usage. I found that my students were highly engaged in these activities, and they proved to be beneficial to their development as readers.

In summary, the teaching of phonics is a foundational component of early literacy instruction. It equips young readers with the tools needed to decode words, build fluency, and enhance spelling skills. However, the key to effective phonics instruction lies in balance — it's not about choosing between phonics all the time or not at all; it's about blending phonics into the fabric of literacy instruction.

By incorporating phonics into shared reading, fun activities, and explicit instruction, early childhood educators empower their students to become confident and skilled readers. In the next installment of our series, we will explore comprehension strategies, bringing us one step closer to unlocking the full potential of our young readers. Stay tuned!

Equip readers with the tools needed to recognize and manipulate sounds embedded within language.

This is the second installment in our Science of Reading series

As the science of reading becomes more influential in the field of education, it is important for us to not only accept and incorporate the principles in our practice, but also make sure we fully comprehend the essence and significance of what it means. Because I am an elementary educator and instructional coach dedicated to nurturing emerging readers, my commitment lies in breaking down the intricacies of the science of reading, while providing support for our young readers' development.

Phonological awareness — much like fluency, the topic of my previous article in this series — serves a crucial role in shaping a child’s reading journey. In this article, I intend to define phonological awareness and offer practical insights for fellow educators. Drawing from my experiences in the classroom as well as my own reading and research, I will explore its significance, its alignment within the science of reading, and provide guidance on fostering it effectively in early childhood settings.

Defining Phonological Awareness

Through my pre-service training, my experiences in the classroom, and ongoing reading and research, my understanding of phonological awareness has crystallized as the capacity to recognize and manipulate the sounds embedded within spoken language. Imagine it as a playground of sounds within the mind, where children identify rhyming words, dissect sentences into syllables, identify individual sounds (phonemes), and play with the rhythm of language. Like fluency, this skill is crucial, serving as the foundation for reading readiness. Strong phonological awareness equips children with the tools to decode words, comprehend texts, and eventually become proficient readers and writers. In essence, phonological awareness is akin to the scaffold that supports the acquisition of language, empowering children to construct sentences, paragraphs, and stories with confidence. It encompasses the following micro-skills:

Strategies for Supporting Phonological Awareness

Recognizing its significance, I have dedicated considerable time to identifying effective strategies and promising practices to support phonological awareness. Drawing from strategies I utilized as a third-grade teacher, coupled with observations from visits to flourishing early childhood classrooms, I want to share three promising practices:

These practices, while adding an element of enjoyment to learning, lay the groundwork for phonological awareness, preparing the stage for successful reading development.

Embracing Phonological Awareness

In the world of reading science, phonological awareness plays a vital role, mixing together words, sounds, and understanding. Just as fluency helps connect understanding and reading, phonological awareness serves as a crucial link between grasping the tiniest sounds within words (phonemic awareness) and linking these sounds to letters (phonics). When we nurture this skill, we help kids confidently deal with reading challenges and build on the fluency we talked about in article one. By recognizing the importance of phonological awareness and finding effective and engaging ways to teach it, we ensure every child embarks on their reading journey with a strong foundation, unlocking the power of literacy and lifelong learning.

Navigate reading mastery and the science of reading to create meaningful instruction for young readers.

This is the first installment in our Science of Reading series

In the realm of reading instruction, fluency acts as a foundational cornerstone, shaping the way readers interact with written language. Often hailed as the bridge connecting decoding and comprehension, fluency plays an instrumental role in molding a reader's overall understanding. This article takes a comprehensive look at the concept of fluency, delving into its significance, practical implications, and its alignment with the science of reading, with a particular focus on the role of guided reading.

Defining Fluency: Beyond the Basics

Fluency in reading goes beyond just being able to read words correctly. It involves reading in a way that is smooth, precise, and with expressive intonation. It also includes accuracy in understanding the text, maintaining a suitable reading speed, and paying attention to prosody, which refers to the rhythm and melody present in language. When all of these elements come together, they transform reading from a basic recognition of words into a skill that allows you to effortlessly comprehend the deeper significance of a text.

Why Fluency Matters: Bridging Decoding & Comprehension

Fluency acts like a bridge that connects two important parts of reading: decoding and comprehension. Decoding is the process of breaking down written symbols into recognizable words, while comprehension involves understanding the true meaning of the text. When a reader becomes fluent, it means they can decode words effortlessly, which in turn frees up mental energy. This newfound mental capacity can then be directed towards better understanding the content of the text. Research has shown a strong connection between fluency and comprehension. Readers who have developed fluency are not only able to grasp complex ideas easily, but also engage in critical analysis of the text. This skill in turn helps them develop a genuine fondness for reading. This dynamic relationship between fluency and effective reading instruction is a central focus within the science of reading.

Guided Reading: A Path to Proficiency

In the array of strategies aimed at promoting fluency, guided reading emerges as a standout approach. Within a guided reading context, small groups of students engage in shared reading experiences, guided by their teacher. The strength of guided reading lies in its ability to:

Guided Reading in Action: Effective Approaches

Elevating Fluency: A Reading Journey

Fluency goes beyond a mere skill; it's the foundation of satisfying, meaningful reading. Guided reading plays a key role in nurturing this skill, supporting capable readers, and fostering a genuine passion for reading. As educators embrace the principles of guided reading and other fluency-centered approaches, they empower young minds to confidently navigate texts. This involves actively connecting and interlinking various elements within the text, much like weaving threads into a fabric. This journey blends the art of reading with the science of effective reading instruction, resulting in a community of skilled and enthusiastic readers. If you are interested in exploring guided reading further, join me at Best Practices for Guided Reading, which will provide you with an opportunity to experiment with designing and implementing guided reading lessons of your own!

Three essential questions to explore as you navigate connecting a curriculum to your classroom.

As the start of the 2023-24 school year approaches, many K-8 educators will find themselves faced with the challenge of adopting a new curriculum. This task can feel overwhelming, leaving teachers and school leaders uncertain about where to begin. To help navigate this process, we can examine three powerful questions that can serve as entry points for understanding and evaluating a new curriculum, helping educators to gain valuable insights needed for making informed decisions that align with their goals and values.

Does it align with school mission & vision?

When introducing a new curriculum, it is essential to ensure alignment with the school’s mission and vision. Consider how a new curriculum reflects the core values, educational philosophies, and goals set by the school. Evaluate whether it supports the desired educational outcomes and adequately prepares students to meet the school’s vision for the future. A curriculum that aligns with the school-wide mission and vision contributes to a cohesive and purposeful educational experience for all students. Evaluating alignment can provide valuable information to inform a school’s decision-making process regarding the adoption of a curriculum and the necessary adaptations and revisions.

Does it support differentiated instruction and diverse learner needs?

Recognizing the diversity of students in a K-12 setting is crucial. It behooves schools to inquire about if and how the curriculum addresses differentiated instruction and caters to students with varying abilities, learning styles, and interests. I would advise schools to look for evidence of accommodations for students with disabilities, support for English Language Learners, and opportunities for personalized learning. Evaluate whether the curriculum provides a range of resources, materials, and strategies that meet the needs of all students. A curriculum that embraces and supports diverse learners promotes equitable access to education and enhances students’ engagement and success. In my experience, differentiation is often a shortcoming of most curricula, so these suggestions can be particularly helpful when it comes to identifying the additional supports and materials that will need to supplement the curriculum.

What assessment methods are incorporated into the curriculum?

Assessment is a vital aspect of any curriculum. When it comes to evaluating and potentially adjusting a new curriculum, inquire about the assessment methods and tools used within the curriculum to measure student progress, understanding, and mastery of concepts. Determine whether the curriculum includes formative assessment to provide ongoing feedback and inform instruction, as well as summative assessments to evaluate student achievement at the end of a unit. Additionally, consider if the curriculum incorporates various assessment formats, such as performance tasks, projects, portfolios, and traditional tests that provide a comprehensive view of students' learning. Understanding the assessment methods and measures helps educators gauge student progress, identify areas for improvement, and tailor instruction. Based on this investigation, you can make the necessary modifications or additions to the curriculum.

As educators embark on a journey of adopting a new curriculum, these questions can serve as valuable guideposts for evaluation. By considering alignment to the school’s mission and vision, supporting differentiated instruction, and assessing evaluation methods, educators can ensure that the chosen curriculum reflects their values, addresses the diverse needs of their students, and provides effective means to measure student learning. Embracing these questions will empower educators to make informed decisions that foster a purposeful and inclusive educational experience for all learners!

Three ways to create a supportive environment that nurtures students' academic, social, and emotional growth.

The beginning of the school year presents a valuable opportunity to establish a positive classroom culture and forge meaningful relationships with our students, creating an environment that nurtures learning, collaboration, and student growth.

Let’s start the year headed in the right direction!

Creating your classroom

The design of your classroom space plays a pivotal role in setting the tone for the entire year. One key aspect to consider is your classroom library. In my own classroom, I loved creating a library, as I believe a thoughtfully curated collection of books has the power to ignite a love for reading and literacy. I aimed to select diverse and engaging books that reflected the interests and experiences of my students, and I worked to make the library easily accessible by using colorful baskets or organizers to store the books. By making the library the centerpiece of my room, I encouraged students to explore and immerse themselves in the vast world of literature. To foster a sense of ownership, I also involved them in identifying trends and connections between texts and let them create themed baskets with corresponding titles. Another important aspect to focus on is the arrangement of desks or tables in your room, aiming for a collaborative, warm, and inviting setup that eliminates students feeling isolated or overlooked. Experiment with different configurations in your room, and assess how they feel from a student's perspective — walk around the room, sit in the chairs, and consider the visibility and opportunities for interaction each arrangement offers. Creating an inclusive and effective physical environment contributes to a positive classroom culture where students feel valued and supported.

Understanding your students

Every student brings their unique experiences, interests, and identities to the classroom. Taking the time to get to know them as individuals helps build meaningful connections and can help us tailor instruction to meet their needs. One approach that I love to use is intentionally selecting mentor texts to inspire student storytelling. For instance, I found Sandra Cisneros' "My Name" from her book The House on Mango Street to be a powerful text that encouraged students to reflect on and share stories about their own names. By analyzing the author's writing style and reflecting on their own experiences, students gained a sense of empowerment and ownership over their personal narratives. Engaging students in activities that explore their surroundings can also provide valuable insights into their lives beyond the classroom. Consider asking students to create maps of their neighborhoods, homes, or any significant spaces in their world. This activity can not only foster a sense of belonging, but also encourages students to reflect on their personal histories and connections to their communities.

Getting to know your learners

Understanding our students' strengths, needs, and learning styles is essential for effective instruction. One way to do this is by gathering any available data from the previous year, including academic performance records and input from previous teachers. This kind of information can help you identify areas where students may require additional support or enrichment. However, we know that data alone cannot provide a comprehensive understanding of your students' learning profiles. Prioritize one-on-one conversations with each student within the first few months of the school year. During this time together, ask about their interests, learning preferences, and goals for the year. By building personal connections and listening to their perspectives, you can better connect to their individual needs and aspirations. This knowledge will enable you to tailor your instruction and provide the necessary support to help each student thrive. Additionally, consider using low-stakes diagnostic assessments to gain insights into your students' abilities. Find opportunities to engage students in games and competitions that allow you to understand their skills in reading, writing, and mathematics. When possible, utilize technology to record and/or analyze their responses. These types of activities can help you avoid overwhelming students with tests while still receiving information that can help you grasp their foundational knowledge and strengths.

Creating a positive classroom culture, establishing personal connections, and understanding your students — both as individuals and as learners — all require intentional effort at the start of the school year. By incorporating these promising practices into your teaching approach, you can help to create an inclusive and supportive environment where all students can thrive academically, socially, and emotionally. Here’s to a new school year. I hope it’s one of growth and success!

Why simply adopting new programs will not guarantee improved reading scores.

Recently, the chancellor of New York City public schools, David Banks, announced a significant change in reading instruction by introducing three researched-based programs with a focus on phonics. While this shift aims to address the flawed approach to teaching reading, it also raises questions about the shortcomings of the current system and the potential consequences of relying solely on phonics instruction.

In this article, I raise concerns about the new programs, the importance of a balanced approach, and propose investing in professional development to improve existing efforts.

Flawed approach to teaching reading

David Banks criticized the City's approach to teaching reading as fundamentally flawed and failing to align with the science of how students learn to read. However, the exact shortcomings are not explicitly defined. Was it the lack of phonics instruction or insufficient emphasis on it? Furthermore, the effectiveness of the current approach seems to be evaluated based on standardized exam scores, which doesn’t provide a comprehensive picture of student learning.

New programs and concerns

The new programs being offered to schools, such as Wit and Wisdom, Expeditionary Learning, and Into Reading, each have their strengths and weaknesses. Wit and Wisdom emphasizes knowledge building but lacks explicit phonics instruction, requiring schools to adopt an additional phonics program like Fundations. Expeditionary Learning includes explicit phonics instruction, but Into Reading has faced criticism for its lack of cultural responsiveness. It is crucial to recognize that there is no magic bullet. No single program can meet the diverse needs of all students, and simply adopting new programs does not guarantee improved reading scores.

Maintaining foundational reading practices

I am not against explicit phonics instruction; however, I want to advocate for the preservation of foundational reading practices, such as read-alouds, independent reading, and shared reading — all of which promote fluency, comprehension, and vocabulary development. While phonics instruction is necessary, it should not overshadow these essential practices that nurture a love for reading and promote student autonomy when it comes to book selection. It is concerning to me that the science of reading is being equated solely with decoding and phonics, which I believe will lead to an overemphasis on this aspect of instruction. Given the limited time available for reading instruction during the school day, other important reading activities may be deprioritized or excluded altogether. This narrow focus could have negative implications for teachers, students, and their overall reading experiences. To teach reading comprehensively, it is essential to consider the interplay between different reading skills. Chancellor Banks highlighted five essential skills reflective of a competent reader:

But these skills are not sequential. They are interconnected and should be taught in a way that recognizes their interdependencies.

Investing in professional development

Rather than perpetuating the narrative of a reading crisis and introducing new programs in haste, I would urge us to invest in professional development for teachers and leaders. This approach would enable them to delve into the science of reading, understand its implications, and identify the most effective ways to teach reading skills. By focusing on all aspects of reading development — phonological awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension — current efforts can be improved, specific curricula can be adapted, and supplementary strategies can be identified.

Promising practices for assessing and adjusting your instruction to meet students' needs.

Data is often thought of as comprehensive spreadsheets consisting of numbers, graphs, and charts, representing scores from end of unit tests or standardized exams. It’s often analyzed to determine whether or not students have mastered content and skills, rather than inform instruction or translate into timely teacher moves in the classroom.

Quantitative data has its place; however, it alone does not suffice. In addition to charts and graphs, teachers need qualitative data to inform and adjust their instruction along the way — throughout the unit, and within particular lessons. So, what are some of the ways teachers can gather this kind of data and make use of it? What can it look like?

A portrait of practice

In a recent visit to a school in Georgia, a colleague and I had the opportunity to perform walkthroughs of select classrooms. One teacher I witnessed — a seasoned math teacher facilitating a lesson on solving equations with decimals — was doing a fantastic job of taking the pulse of her classroom and assessing the needs of her students throughout her lesson. I want to share what I observed as I think it can be a useful case study to help us answer the above questions. She posed a question for the do now, and after circulating to assess how her students were doing, she addressed the class: “Okay y’all, I want us to stop for a minute. I’m noticing that what is tripping us up with this problem is rounding, and I would hate for this small detail to result in us getting these types of problems wrong!” From there, she asked students to look back at their problem, particularly to see if they rounded correctly, while she prepared the next step of the lesson on her computer. After a few more minutes, she asked the students to go back to their seats, and informed them that they were going to engage in a Kahoot, to provide more practice with rounding. (Kahoot is a wonderful tool for not only offering practice, but also for gathering data quickly and accessibly. After each question, Kahoot offers a chart indicating how many students selected which answer and whether or not it was the right answer.) This was a simple and effective way to gather and use data in the moment, in order to shift the plan for the day’s instruction. Rather than push forward, she took stock of what was needed, and responded intentionally. And it didn’t stop there. As the lesson progressed, she continued to gather data while students were working, and made shifts based on what she observed. I watched her create a few different groups based on the information she had: one for students that needed more rounding practice; another group that focused on the original practice problems for the day; and another group that was pushed with some more challenging questions based on their strengths. This case study offers some promising practices for gathering and analyzing data, and making in the moment adjustments to instruction. In addition to the practices I described, I want to offer a few more that I utilized while I was leading my own classroom.

Turn and talks

Turn and talks are an effective means of assessment that I leaned on heavily during my time as a classroom teacher. Given my large class size, turn and talks allowed me to check for understanding with more students than I could if they were working independently. I often used turn and talks as part of a do now, where I would pose a question and then have students talk to a shoulder partner while I circulated and listened in on their conversations. Additionally, I liked to use turn and talks as part of a guided practice where I would model a strategy and then have students try it out with a partner while I listened and observed. I sometimes used a checklist to make note of which students seemed to be getting it and which students might need some more support, to inform how I might group my students for the lesson and inform who I might need to conference with individually.

Conferencing

Conferencing is another powerful formative assessment that can be very instructive for both teachers and students. Conferences, when executed effectively, involve looking at student work, asking some clarifying and/or probing questions to determine what a student needs, in the moment, as they practice a new skill. Based on this investigation, the teacher identifies a high-leverage strategy that can advance student learning, often models it, and then observes while students give it a try.

Collecting and sorting student work

Lastly, collecting and sorting student work is an effective means of assessment that can be particularly informative for sequencing instruction. As an elementary teacher, I would make it a point to collect student work once a week, whether it was students’ writing notebooks, their reading post-its, their drafts of writing, etc. I would look closely at the work to try and determine strengths and struggles, and then identify any common trends that could inform my grouping as well as the goals I should set for these groups. For example, if we were working on a writing unit focused on non-fiction essays, I might review student work and notice common challenges related to students supporting their thinking with evidence, using proper citations, analyzing the evidence to make connections to their claims, etc. I would sort the challenges, and attempt to narrow them down to three or four that would form my groups, and then identify a teaching point for each that I would implement the following week. It often felt like a lot of work, but when I did it, I always found it enlightening and I appreciated how it pushed me to ensure I was catering my instruction to what my students truly needed. (A twist of this for middle and high school teachers could be to collect and sort exit tickets, as they are likely more manageable than collecting drafts.)

As teachers, we need to understand and address our students' needs as they arise, as they engage in the learning process and acquire new skills. In doing so, we can reflect on and improve our instruction before it’s too late. What I hope I have provided are meaningful and manageable ways to gather qualitative data and make use of it in the moment and beyond.

Breaking down the science of reading to identify specific skills & supports for emerging readers.

Many people are talking about the science of reading — a term that is certainly not new, but has been gaining some serious traction recently, and prompting some heated debate. This debate largely stems from how this term is being interpreted and what this means for the students in our classrooms. What is truly meant by the science of reading?

After doing some of my own research, I’ve come to understand the science of reading as a comprehensive body of cross-disciplinary research conducted over the last 20 years that deepens our understanding of how the brain learns to read, including what skills are involved, how these skills are connected, and which parts of the brain are responsible for our reading development. The research seems clear, but because the term has become so loaded, I believe we are losing sight of what our young learners really need to become strong, capable readers.

What makes a skilled reader?

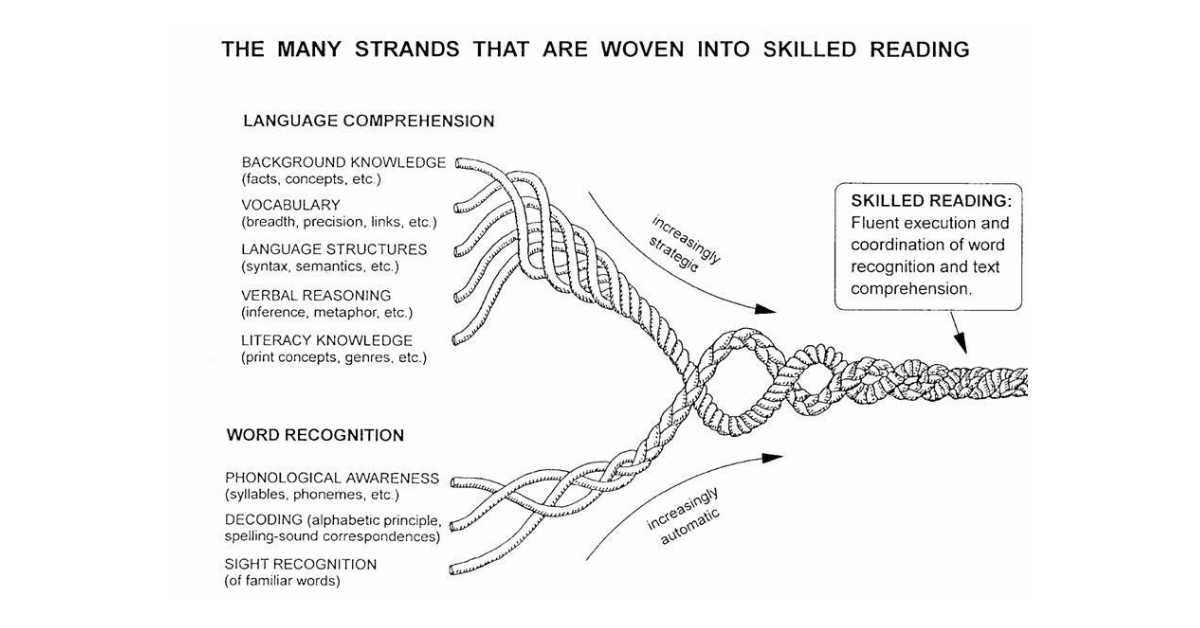

One of the leading researchers of early language development and its connection to later literacy, Dr. Hollis Scarborough, developed in 2001 what she termed the Reading Rope, which helps us articulate the specific skills readers need to have in order to be proficient. The rope consists of lower and upper strands, with the upper strand focusing on language comprehension, and the lower strand emphasizing word recognition. All these micro skills start to work together through practice and repetition, so that these skills can become instinctive. Ideally, over time, language comprehension becomes more strategic and weaves together with word recognition to produce a skilled reader.

I have greatly appreciated Dr. Scarborough’s work, and recognize connections to how I have and continue to talk about the reading development in my coaching work. Despite using a few different terms, we have similar meanings. What she describes as literacy knowledge, I have described as concepts about print. Similarly, we talk about comprehension as consisting of micro skills including vocabulary and background knowledge — the skills needed to make sense and meaning of a text.

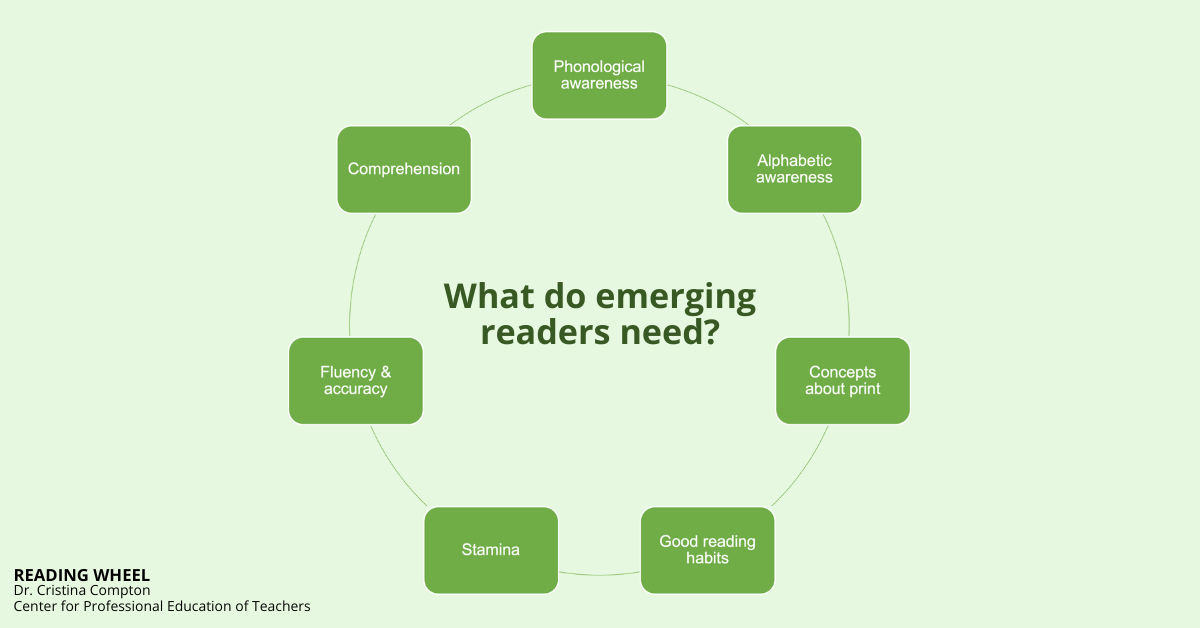

However, I have gone a bit further in my explanation of what emerging readers need and have developed the Reading Wheel, which is based on my understanding of research and my experience as a childhood educator, teaching students how to read.

You’ll see that, in addition to phonological awareness, I include alphabetic awareness, which is defined as “knowledge of letters of the alphabet coupled with the understanding that the alphabet represents the sounds of spoken language and the correspondence of spoken sounds to written language.”

I also discuss the importance of good reading habits, which include what Dr. Scarborough describes as verbal reasoning and a few others. Good reading habits are those often taken for granted skills that proficient readers use when reading — predicting, evaluating, questioning, clarifying, and monitoring for meaning, for example. In my work with teachers, I try to have them engage in the reading of a text, and then reflect on some of the moves they made while reading, to help reveal the habits they utilize most, and how these might be incorporated into their teaching. I also include a specific focus on stamina, which I define as the skill of being able to read for longer and longer periods of time, and the willingness to keep reading, even when it feels hard.

What support do readers need?

To me, all these skills are equally important. The problem arises when we place more value or importance on certain skills over others — e.g., word recognition over language comprehension, which has often resulted in phonics instruction, all the time! Phonics instruction has its place when it comes to helping children learn the relationships between the letters of written language, the sounds of spoken language and supports their phonemic awareness and decoding skills; however, phonics instruction alone would not suffice. Emerging readers need opportunities to recognize the word patterns and letter blends in context, as they show up in books. If we look closely at both Dr. Scarborough’s Reading Rope and the Reading Wheel, we’ll see that they underscore the importance of being able to read words AND make meaning, evident by the weaving of the individual threads of the rope and the circular nature of the wheel. Students need explicit instruction when it comes to developing comprehension skills, in order to support them in thinking critically, making connections, and developing their identity as readers. Young readers need differentiated instruction and in the moment feedback as they work to progressively read more complex texts. This often happens during readers' workshops, or small group instruction, such as guided reading. Lastly, children need opportunities to engage in independent reading and participate in read alouds, to gain exposure to a wide range of texts aligned to their needs and interests, to grapple with different topics and content, to help foster a love for reading, promote stamina, and learn meaningful habits from a skilled reader — their teacher. My students loved read alouds, and often begged me to read more, so they could find out if Clover and Annie end up as friends in The Other Side, or find out if and how the teacher will respond to the class making fun of Chrysanthemum, or find out the connection between Kissin’ Kate Barlow and the Warden in Holes.

As Diana Townsend states, “If we really care about teaching kids how to read, we need to focus on creating space and time for teachers to enhance their professional knowledge." They need time to explore the research around reading development for themselves and engage in conversation with colleagues about how it should inform their instructional strategies and approaches, rather than relying on a packaged curriculum or reading programs to do it for them.

Furthermore, there needs to be meaningful and ongoing inquiry, where teachers can try things out, and then reflect on what’s working, when, for which readers, and why, as we know it takes time and patience to get things “right.” At the end of the day, Townsend reminds us that, “no one is going to ‘win’ the reading wars and children will always be the losers.”

Strengthen the connection between the why and how of student learning, cultivating essential 21st century skills along the way.