|

Nurture confident readers by blending phonics into the fabric of your literacy instruction.

This is the third installment in our Science of Reading series

When it comes to early reading instruction, few topics have sparked as much debate and controversy as the teaching of phonics. Over the years, the pendulum has swung between extremes: some advocate for phonics as the exclusive focus of instruction, while others argue for its complete exclusion from the curriculum. However, the crux of effective literacy education lies in finding a harmonious balance. As part of my series dedicated to unraveling the science of reading and nurturing young readers, we embark on a journey into the world of phonics. What exactly is phonics, what role does it play in reading development, and how can early childhood educators incorporate it into their classrooms through a balanced approach?

Defining Phonics: The Foundation of Reading

At its core, phonics is the relationship between the sounds of spoken language and the letters that represent those sounds in written language. It's the code that unlocks reading comprehension. Phonics instruction involves teaching students how to connect the sounds of spoken language (phonemes) to the symbols (letters or letter combinations) that represent them (graphemes). We dig deeper into this topic in my previous article, which examines how to nurture phonological awareness in emerging readers. Phonics equips young readers with the skills needed to decode words — without phonics, the process of learning to read would be like trying to solve a complex puzzle without understanding the individual pieces.

The Purpose and Importance of Phonics

Phonics serves several crucial purposes in the development of young readers: Decoding Words: Phonics provides the key to unlocking unfamiliar words in texts. When students understand the relationships between sounds and letters, they can sound out words they haven't encountered before. Building Fluency: Proficiency in phonics helps build reading fluency. Fluent readers can read with accuracy, speed, and expression, which enhances comprehension, as we have discussed in previous articles. Spelling Proficiency: Phonics instruction also contributes to spelling skills. When students know the sounds associated with letters and letter combinations, they can spell words more accurately.

Balancing Act: The Key to Phonics Success

A balanced approach to phonics instruction is essential in literacy education for several reasons. Firstly, it facilitates a well-rounded development of essential reading and writing skills, encompassing phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, and writing proficiency. This holistic perspective acknowledges and embraces the diversity of learners, accommodating various learning styles and individual needs. The integration of phonics within authentic reading and writing contexts is a critical aspect of this approach. By immersing students in real-world applications of phonics skills, it not only reinforces learning, but also enhances reading fluency. This equips students with a range of word recognition strategies, lessening their reliance solely on phonics, and thereby improving reading efficiency. Furthermore, a balanced approach recognizes that the ultimate goal of reading is comprehension. It weaves phonics instruction together with comprehension strategies, ensuring that students not only decode words, but also understand and interpret the text they read. Creating a balanced approach to instruction can offer essential support for struggling readers, tailoring instruction to meet their specific needs and providing a scaffold for their literacy development. Ultimately, it fosters a deep appreciation for literacy, nurturing lifelong reading and writing habits, and in doing so, it aligns with evidence-based practices in literacy education.

A Balanced Approach In Action

As a third-grade teacher, I often recognized the need to teach phonics to specific groups of students, even though it wasn't a part of the standard curriculum. One approach I used was phonics through literature, where I selected books featuring specific phonics patterns, and integrated phonics instruction within shared reading sessions. For example, if I wanted to focus on the long a sound spelled with the silent e pattern (e.g., "cake," "gate”), I could use a book like Jake Bakes Cakes, which prominently features words with this pattern. I would then use this text to engage in a shared reading session, where I read the book aloud to the class, pausing at words with the target phonics pattern. For instance, when we encountered the word cake, I might emphasize the long a sound and point out the silent e at the end of the word. After reading, I would engage the students in a discussion about the phonics pattern, asking questions like, "What sound does the e make at the end of the word cake?" or "Can you find other words in the story with the same pattern?" To support word recognition, I would encourage students to identify and read words with the target pattern in the book. They might take turns reading sentences or identifying words on specific pages. I would also have students use magnetic letters or word cards to demonstrate how changing the vowel sound (e.g. cake to make) affects the word's pronunciation and meaning. Students would then manipulate letters to create new words following the same pattern. If there was time, I would also ask students to engage in word play activities related to the phonics pattern, such as creating rhyming words or making word family charts, to reinforce the concept. As a follow-up activity, students might be encouraged to write their own sentences or short stories using words with the target phonics pattern. The key idea behind phonics through literature is that phonics instruction is embedded within the context of enjoyable and meaningful texts, fostering a love for reading and connecting phonics to authentic language usage. I found that my students were highly engaged in these activities, and they proved to be beneficial to their development as readers.

In summary, the teaching of phonics is a foundational component of early literacy instruction. It equips young readers with the tools needed to decode words, build fluency, and enhance spelling skills. However, the key to effective phonics instruction lies in balance — it's not about choosing between phonics all the time or not at all; it's about blending phonics into the fabric of literacy instruction.

By incorporating phonics into shared reading, fun activities, and explicit instruction, early childhood educators empower their students to become confident and skilled readers. In the next installment of our series, we will explore comprehension strategies, bringing us one step closer to unlocking the full potential of our young readers. Stay tuned!

Navigate a four-part cycle that will help you develop effective assessments and determine students' needs.

Adapted by G. Faith Little from CPET’s Handbook: Design Your Own ELA Assessments, by Courtney Brown and Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang.

As educators, we assess our students in multiple ways for many purposes: to evaluate what they know and can do based on the skills and content that we teach them, to make instructional decisions, and to reflect on teacher practice. Quizzes, in-class activities, homework, and writing assignments are all opportunities to find out how our students are achieving. By analyzing and interpreting the results of these tasks, we can determine the needs of students and adjust our teaching to help students succeed.

Periodic assessments are low-stake assessments designed to provide timely and detailed information on students’ strengths and weaknesses, as well as their progress over time. The results from the assessments are used by teachers as data to inform instruction. They can also be used to start and deepen communication with parents / caregivers who can support their students’ learning outside of the classroom.

Establishing learning goals

The assessment and rubric development cycle begins by establishing learning goals. Wiggins and McTighe (2005) pose these helpful questions: "What content is worthy of understanding? What enduring understandings are desired?" Addressing these questions will help teachers establish learning goals for the entire year, as well as individual units. Periodic assessments should be designed to measure students’ progress in these learning goals and relate directly to the content of teachers’ instruction, i.e., books, plays, stories, etc. These goals, in ELA, for example, should relate to the reading process, knowledge of literary conventions, making meaning (analysis), and communicating in writing. When teachers develop learning goals together, there is cohesion and focus in how the school supports students’ learning. In any content area, learning goals specify the crucial understanding teachers expect students to develop and the key skills or competencies students should demonstrate. Learning goals for periodic assessments can be developed by teachers, often working together within a school, and referencing important resources, including state mandated learning standards and performance indicators, schoolwide learning standards, disciplinary criteria, and teachers’ own expectations for student performance. Articulate learning goals by answering the following:

Ready to begin mapping our your goals? Download our Learning Goals worksheet.

Developing assessments and rubrics

Assessments Formative assessments are those that focus on the students’ performance as they develop important knowledge and skills — they’re meant as benchmarks or milestones along the journey rather than the final destination. Teachers can use the data from these assessments to determine future instruction. Periodic assessments should be aligned with student performance standards, learning goals, and the curriculum in each unique learning community. While each assessment (Fall, Winter, and Spring) may look different, designers should carefully consider how the assessments measure students’ growth throughout the entire year. These assessments will provide valuable feedback for teachers to improve instruction, align to standards, and measure student growth. These curriculum-embedded assessments have great potential to inform teachers and schools of the students’ progress toward established standards. Curriculum-embedded means an assessment is designed to reflect the actual curriculum being taught in the class. This is in contrast to most standardized tests, which generally do not pertain to the curriculum taught in individual classrooms. The chosen approach often influences the type of data accumulated. Aligned assessments

Description

Each assessment maintains the same format and requirements. Many teachers have used similar persuasive writing prompts with the same requirements for each assessment. This approach allows for consistency and assessment routines. Data information Since each assessment is very similar, teachers are looking to see students’ scores increase on each assessment. Longitudinal score results are reliable because the assessments are similar and the same rubric is used for each one. Teachers can identify areas where scores do not increase as areas in need of additional instruction. Progressive assessments

Description

The assessments become progressively more difficult, to reflect the growing knowledge and abilities of students. The assessments are designed to reflect the latest content unit as well as yearlong learning goals. This approach allows for flexibility and takes a snapshot of student learning. Data information Since each assessment gets progressively harder, maintaining scores indicates students are learning and growing. Score results directly reflect the most recent instruction and show what information students did not fully grasp. Teachers can make determinations about what should be reviewed or revisited from a new approach. Project-based assessments

Description

The assessments are inextricably connected to the classroom units and allow for students to express learning in multiple forms. Project-based assessments are designed to reflect the latest content knowledge through authentic (real-world) projects. Data information Since many of these authentic assessments include a publication or performance, an early draft of the project may be used as the assessment because it represents the students’ own work without additional assistance. Teachers see scores as reflective of “live knowledge” and immediately use the data to identify important lesson topics and share feedback with students so they can revise. Responsive assessments

Description

The assessments are designed to measure growth in specific areas, based on information learned by analyzing the data and student work. Responsive assessments attend to the needs presented by the students and they inform specific areas where instruction should be elaborated. Data information Since these assessments are designed as a response to the data, the support structures in each assessment may increase or decrease, depending on the time of year. Areas where students are scoring poorly may indicate that increased support is necessary for the next assessment. When analyzing the data, teachers are primarily interested in how students are performing in these specified areas where they’ve made changes in an effort to increase student performance. Rubrics The rubric, a scoring guide that uses descriptors for every performance level, is an essential component to any assessment. While rubrics may come in many shapes and sizes, the most effective rubrics are those that encapsulate the focus dimensions of the assessment and clearly describe the strengths of the performance at every level. Rubrics are most effective when they are assessment-specific because they are created for the precise task and requirements of the assessment, unlike all-purpose rubrics, which are often broad or ambiguous to account for a wide variety of assessments. The following ten criteria (adapted by Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang from the work of Dennie Palmer Wolf of the Rethinking Accountability Initiative at the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University) mark the foundations for creating an effective rubric that reliably evaluates student work:

Frequent pitfalls of rubric design

Too much / too little information Too much information and the rubric bleeds on to too many pages, the expectations are barely read, and it can be difficult to use. Too little information leaves too many qualities of the assessment undefined, and therefore, difficult to score. Consider aiming for 3-6 dimensions and performance levels with 3-5 consistent qualifying statements for each. Vague, ambiguous, confusing or contradictory language Consider using descriptions that clearly explain what the student did. Professional or exclusive language vs. inclusive language Be careful not to exclude students from understanding the rubric by using ultra-sophisticated or academic language. The most popular buzzwords don’t always make the best rubric descriptors. Use student-friendly language that capitalizes on words and phrases commonly used in the classroom. Expectations for assessment misaligned with the rubric Be sure to align the rubric with the learning goals and the assessment. It’s crucial that designers pay close attention to the assessment requirements and the rubric language because if something is not on the rubric, it cannot be used as a factor for evaluation. Scoring is inconsistent with performance levels If scores seem inconsistent with the performance levels (for example, a student earned “Proficient” but only earns a score of 2 or 65%) it may be necessary to revise how the scores were assigned to each level. Consider testing the rubric scoring system to be sure numeric scores or percentages are accurate to their performance level.

Designing assessments & rubrics is important and challenging work. Partner with CPET to create customized materials and support successful implementation of effective tasks, assessments, and rubrics!

Scoring assessments

All assessments must be scored in order to produce the data used to inform instruction. When scoring assessments, we recommend that schools use a team approach, which may include both teachers from the specific content area and teachers from other disciplines. This promotes school-wide collaboration, builds community, and supports reading and writing across the disciplines. Team members should prepare to score by taking part in a “norming” process, reviewing and discussing the task to clarify what the students are asked to do and what teachers expect to see in their work and become familiar with the rubric. Next, it is useful to have a “norming discussion”: everybody reads and discusses several samples of student work from the assessment task, each teacher scores the work individually, and then group members share scores and discuss how they used the rubric to score the student work samples using evidence from the papers to justify their scoring. Once teachers feel comfortable with using the rubric, teachers should score the students’ work from the assessment. We suggest building in a “reliability check” process to make sure that the students’ work is being scored fairly and consistently so that the data will be reliable. Periodic assessments are most useful when scored as soon after the administration of the assessment as possible, so the data is relevant and timely. The longer the gap between students’ taking the assessment and the data report, the less useful in informing instruction the data will seem to teachers and administrators. SAMPLE: An approach to collaborative scoring

Two important common principles: (5-10 minutes)

Clarifying the task (20 min)

Norming (30 - 45 min) Distribution of copies of assessment #1

Scoring (duration depends on task content / length) First Scoring

Score comparison (duration depends on how scores match up)

Mediation (if necessary)

All assessments with final scores should be returned to facilitators. Woohoo! We did it!

Analyzing data

Data comes in many forms and is used every day by teachers to help plan instruction and adjust our teaching. Quizzes, essays, homework, standardized tests, and attendance records are all data. Teachers’ observations of students at work are also an important form of data. Students’ responses and behavior are data. No one form of data will give a complete picture of a student’s achievement. There is no shortage of usable data; however, it is how we collect and analyze the data wisely to inform teaching and learning that matters. This step in the cycle specifies a systematic process, one that allows us to look closely and analyze the data. A careful analysis of the data will yield important information about our students’ strengths and weaknesses. Based on this information, schools and teachers can develop or revise learning goals, and teachers can plan specific instruction for a class and/or individual students to best address students’ needs. We suggest that data discussions be carried out among specific content area teachers and with colleagues from other disciplines. This will allow teachers across the curriculum to identify and address students’ needs — for example, organizing an argument in writing, using evidence to support their thesis, articulating rationale for a solution to a problem or a hypothesis, etc. Data is any form of information collected together for reference and analysis. Another way to understand data is as evidence of desired results. In the case of periodic assessment data, scores from student work provide data for understanding how students are performing related to specific learning goals. This is where curriculum-embedded assessments can be most powerful. You actually have to anticipate the kinds of data that will be useful as part of developing a unit of study. The data may be used to answer questions about whole class performance and individual student performance. The data reports will also help teachers to adjust instructional strategies to address students’ needs — e.g., what might need to be retaught or taught differently?

Ready to communicate with a student about their strengths and goals? Download our Individual Plan for Improvement Sample to use when sharing data with students.

Continuing the cycle

Assessing students is most valuable as part of a cycle that begins with establishing student learning goals and involves developing curriculum-embedded assessments and rubrics, administering the assessments, scoring them, and analyzing the data they produce to inform instruction. Keep the cycle going from baseline to end of year assessments!

Create clear and consistent procedures that communicate classroom expectations to students.

The list of a typical teacher’s responsibilities is long — in addition to curricular work, lesson planning and implementation, monitoring and assessing students’ learning, offering feedback to students, parent communication, and so much more, teachers are also responsible for making sure that all aspects of learning and the classroom are organized and safe. The work can feel endless.

It is a hefty responsibility to plan for and implement procedures for all transitions or movements in and out and around the classroom. However, once you have developed and implemented some simple, clear, and consistent procedures, the work can feel less daunting and move more smoothly!

Locating routines

The initial notion of the Three Rs — Reading, (w)Riting and ‘Rithmetic — as the foundation of learning and education is clearly too narrow, especially as we move more firmly into the 21st century. Instead, reinterpreting the Three Rs as Routines, Rituals, and Relationships makes more sense as guiding principles for today’s classrooms. First, let’s take a closer look at how routines, rituals, and relationships help us make key decisions as we cultivate our classrooms. Rituals are different from systems and procedures, because their main goal is to create and sustain community and support an inclusive culture where all students feel welcome, safe and appreciated. Rituals may be instilled as you start up the year, and they will also develop authentically as you get to know your students. Relationships include the development of connections between teacher and student, and also amongst students and their families. This includes developing and maintaining relationships with students, restoring relationships when conflicts or tensions arise, and sustaining positive communication. Routines are often where we begin, as they are a crucial starting point to creating the classroom culture. They may be defined as systems for managing the complexities of a classroom space and any procedures for making the class run smoothly. I like to think of classroom management not as managing students, but rather as managing the space, whether it is digital, hybrid, or in person.

Setting up the space

Before we establish classroom routines, we need to set up the physical space and make choices about how best to use it. The way we set up our classrooms creates not only organized and smooth classroom operations, but lays the groundwork for a welcoming environment for all our students. Many factors determine the set up of the classroom, including how much space is actually available! Remember to be flexible and adapt your classroom setup — including your students’ seating — based on how your students work best together, your instructional goals, and your students’ evolving needs. Considerations & examples

Shaping seating charts

Just as important as how the basics of your classroom space will function is where your students will sit. Some of us may be ambivalent about using seating charts, as they might conjure up old-fashioned, controlling images of classrooms and teaching. Some teachers, on the other hand, swear by a seating chart in their classrooms. I encourage all teachers to start with a seating chart, even if it is simply alphabetical, so that you can get to know your students and also observe their interactions and dynamics. Then, after you’ve gotten to know the class better, you can make adjustments as needed. These adjustments can stem from observations about student behavior, but also from your instructional goals, as mentioned above. Ashlynn Wittchow reminds us to “let the space work with you, not against you,” and she encourages teachers to let students know that the seating and layout will change over time. Imagine Schools also offers some inspired ways to maximize classroom space while remaining flexible and student-centered. Considerations & examples

Shifting to routines

During my time as a teacher, I learned pretty quickly that not only setting up routines, but discussing and practicing them with my students, was key to making them meaningful for my classroom. Once my space was set up, I needed to consider how students would enter and exit the classroom, how we would handle the distribution or collection of materials, and even how students would re-enter class after being absent. Each of these pieces have an influence on students’ understanding of the roles and expectations within a classroom, which in turn, can impact their learning experience. Below are some typical categories for classroom routines, as well as some factors to consider as you make decisions, and examples of what these routines can look like in practice. Entering the classroom

Starting class

Distributing & collecting materials

Engaging in digital learning

Evaluating additional procedures

Ideally, we establish classroom routines at the beginning of the year, during a period in which both we and our students are engaging in a fresh start. However, it is never too late to re-evaluate or re-establish routines with your students, if you discover gaps in classroom management or that your students have outgrown existing structures.

Encourage meaningful reading habits as you ask students to engage in a dialogue with their text.

Over the past few years, I have heard more and more middle and high school teachers agree about how difficult it is to “get kids to read." I have observed myself that few students seem to be reading full length books independently, and by choice. Of course, there are so many reasons for these observations.

Let’s zoom out a bit to think about the state of reading for most of our students: in the past, reading was not only a major form of entertainment, but a crucial source of information. Time for reading was not in competition with an expansive, alluring digital world offering games, web surfing, Tik Tok, Instagram, endless TV and YouTube channels, etc. Even as adults, we know how easily accessible and comforting these modalities are. Technology offers us so many easy, even addictive options. Technology has also made it easier for students to “read” or pretend they have read an assigned text by scanning summaries of chapters, Googling quotations from the text, watching video versions, etc. Information that we may have needed to access by reading a book is now available at the click of a finger or by saying a few words to AI. We have all been there — we even have a term for this, tl;dr, or too long, didn’t read. Research confirms my own observations that few young people are reading on their own or consider “reading for pleasure." The Pew Research Center asserts that, “few late teenagers are reading many books” and a recent summary of studies cited by Common Sense Media indicates that American teenagers are less likely to read ‘for fun’ at seventeen than at thirteen.” The pandemic also seems to have derailed some students’ academic reading habits, which have proven to be like muscles that need to be exercised more regularly than we previously knew. All of this means that if we want our students to read, to become strong, confident readers, and maybe even enjoy reading, it is crucial for educators to make reading meaningful and relevant for our students, and not simply “cheat proof."

Encouraging students to read

Offering students choices of relevant books to read and discuss together in book groups or pairs is a fantastic way to encourage them to engage in reading. However, most educators agree that reading a book together — as a shared “anchor text” for the whole class — can also be important and lead to powerful discussions and collective learning. Mike Epperson — a teacher with whom I work closely in the South Bronx — took the opportunity to bring a shared anchor text to his 10th grade classroom, introducing his students to Elie Wiesel’s Night. While Night is a riveting, significant story and a relevant choice for 10th graders, who are concurrently learning about World War II and the Holocaust in history class, that doesn’t guarantee that students will engage in the reading. Mike was concerned about ensuring that his students were both engaged deeply and personally in the important subject matter and took it seriously. He decided early on that he wanted students to read the entire book. Mike strategically layered his teaching unit with Night at its core, along with supports and entry points to encourage high engagement, including: background building about the Holocaust, Anti-Semitism, and Judaism, and a careful sequence of lessons that focused on a key topic in a section of the book. Additionally, to encourage reluctant or less confident readers to read daily and remain engaged in reading the whole book, Mike emphasized and taught annotation. Since the school had copies of the book left over from ordering during the pandemic, Mike was able to give each student their own book to write in and keep. These two simple pieces — students having a book of their own and an opportunity to talk back to the text through annotation — created an environment ripe for close reading and high engagement.

Encouraging students to annotate

Getting students to annotate in their actual books wasn’t as simple as Mike had expected — he recalls that “when we first started annotating, some students expressed resistance because they didn’t want to make the nice-looking book look ugly. One student compared it to writing on a beautiful painting with crayon.” However, as time went on, students were “able to find a way to annotate that helped them preserve the beauty of the original text. I believe that as students took on a self-appointed role as the book’s preservationists, they ended up developing a deeper respect for the content of the book as well.” As the students connected more personally with the book and the character of Elie, Mike began to see that the act of authentic annotation was offering students an unanticipated opportunity for creative expression. He shared that “a lot of students like drawing, and there’s a similar appeal in annotation. While annotating is not drawing, a fully annotated page is visually pleasing. Some students’ annotations are neat, symmetrical, and visually appealing in a way that suggests that students take pride in how their annotations look. I think this fosters a sense of pride in the content of their annotations, too.” Mike’s observations of his students’ annotations confirm the belief that writing as you read makes your thinking visible, and can create an engaging conversation as we talk back to the text. He puts it simply: “Annotation gives the students a more active role in reading. They get to have a voice, even if no one else will see their annotations.” The students are no longer alone with a book. They are in dialogue.

Suggestions for successful annotation

When I visit Mike’s classroom, students eagerly show me their annotations and explain the significance of both specific lines on a page and their connections to larger themes. A number of students also tell me how much annotation is helping them “remember’ and “understand” past parts of the story. They are clearly proud of their text marking and meaning-making. Based on my observations of Mike’s classes, I’d like to offer some simple tips for making annotation a successful approach with your own students:

Hopefully, you will feel inspired to introduce or continue using annotation in your classroom! As you encourage students to read with their pen and engage in a dialogue with a text, feel free to adjust any of the strategies above to match the readers and annotators in your classroom.

Equip readers with the tools needed to recognize and manipulate sounds embedded within language.

This is the second installment in our Science of Reading series

As the science of reading becomes more influential in the field of education, it is important for us to not only accept and incorporate the principles in our practice, but also make sure we fully comprehend the essence and significance of what it means. Because I am an elementary educator and instructional coach dedicated to nurturing emerging readers, my commitment lies in breaking down the intricacies of the science of reading, while providing support for our young readers' development.

Phonological awareness — much like fluency, the topic of my previous article in this series — serves a crucial role in shaping a child’s reading journey. In this article, I intend to define phonological awareness and offer practical insights for fellow educators. Drawing from my experiences in the classroom as well as my own reading and research, I will explore its significance, its alignment within the science of reading, and provide guidance on fostering it effectively in early childhood settings.

Defining Phonological Awareness

Through my pre-service training, my experiences in the classroom, and ongoing reading and research, my understanding of phonological awareness has crystallized as the capacity to recognize and manipulate the sounds embedded within spoken language. Imagine it as a playground of sounds within the mind, where children identify rhyming words, dissect sentences into syllables, identify individual sounds (phonemes), and play with the rhythm of language. Like fluency, this skill is crucial, serving as the foundation for reading readiness. Strong phonological awareness equips children with the tools to decode words, comprehend texts, and eventually become proficient readers and writers. In essence, phonological awareness is akin to the scaffold that supports the acquisition of language, empowering children to construct sentences, paragraphs, and stories with confidence. It encompasses the following micro-skills:

Strategies for Supporting Phonological Awareness

Recognizing its significance, I have dedicated considerable time to identifying effective strategies and promising practices to support phonological awareness. Drawing from strategies I utilized as a third-grade teacher, coupled with observations from visits to flourishing early childhood classrooms, I want to share three promising practices:

These practices, while adding an element of enjoyment to learning, lay the groundwork for phonological awareness, preparing the stage for successful reading development.

Embracing Phonological Awareness

In the world of reading science, phonological awareness plays a vital role, mixing together words, sounds, and understanding. Just as fluency helps connect understanding and reading, phonological awareness serves as a crucial link between grasping the tiniest sounds within words (phonemic awareness) and linking these sounds to letters (phonics). When we nurture this skill, we help kids confidently deal with reading challenges and build on the fluency we talked about in article one. By recognizing the importance of phonological awareness and finding effective and engaging ways to teach it, we ensure every child embarks on their reading journey with a strong foundation, unlocking the power of literacy and lifelong learning.

Overcome common language learning myths to view multilingual students as assets, not liabilities.

Multi-Language Learners, or English Learners, are one of the fastest growing populations in our nation. Whether students are immigrating to the US anywhere in their journey from Pre-K to 12th grade, or English is not their primary language at home, educators are in need of support when it comes to language learning across grades and content areas. We examine this topic, dispel common myths, and discuss how to support these students in our Support for Multi-Language Learners episode of Teaching Today, where our host Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang is joined by Maria Garcia Underwood, Founder and CEO of M. Ideas Consulting, and yours truly, Lead Professional Development Coach here at CPET.

All terms for language learning are the same

In the episode, we highlight three key terms and define how they are different. Although these terms all have something to do with language learning, they are not synonymous. Here is a quick breakdown of what some language learning terms mean:

Throughout the rest of the episode, we use the term MLLs.

Teaching a foreign language is the same as teaching English

How we teach language matters when considering the context in which we are teaching. Teaching English when English is the dominant language of instruction requires different teaching practices than teaching a foreign language to students. Maria asks us to consider the motivator behind language acquisition when we learn our first language: communication. When thinking about our MLLs, their main goal is to “acquire English for communication purposes, for their everyday reality, for their everyday survival, both in those six hours at school, and outside.” This is very different from acquiring a language for the purpose of being able to communicate abroad when you’re on vacation or a business trip. Unfortunately, some of our teaching practices for English learning do not always mirror this basic need. Think about a one-year-old. Are you teaching that child grammar and verb conjugation? I hope not. That’s not how language is exposed to children. We focus on communicating, forgiving their mistakes, and ensuring their access to language grows. How can we use this model for our MLLs? Consider their basic needs. What do they need to understand and communicate throughout the school day to feel comfortable and safe? This ranges from understanding the school schedule to how they indicate the need to use the restroom. This contextualizes the language for them and creates the space to continue learning. We also need to consider the role of language when accessing content. As a high school English teacher, not only was I responsible for helping my students acquire a new language, I was also responsible for helping them learn how to write a personal essay for college applications. I worked with my bilingual students to create instructions on how to write personal essays and research papers in Spanish (the primary second language spoken at my school) because as far as I was concerned, the English could come later. Of course I wanted my students to feel confident in their English language abilities, but they also needed to understand the reasoning behind a thesis statement or how to use supportive evidence clearly. This content was essential, similar to the elements of a lab report or explaining a proof in math. Learning a language to access content is very different from learning a language as content.

It only takes a few years to master a language

To dispel this myth, we turn to the work of Dr. Stephen Krashen, an American linguist and Emeritus Professor of Education at the University of Southern California. He outlines five levels of language acquisition (different from state determined levels for testing) and an average timeline for transition:

As educators, we must consider how long it takes the average language learner to reach the Advanced Fluency level. We might hear students having conversations with their peers in the hallway, but those social situations require what Dr. Jim Cummins, professor for the Studies in Education of the University of Toronto, considers Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills, or BICS. These conversations require different skills from classroom language, which Cummins considered Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency, or CALP. Students who are able to use conversational language are moving through the levels of language acquisition, but educators must be careful not to assume that just because a student is fluent in social language, they are also fluent in academic language. For more information specific to BICS and CALP, check out Colorín Colorado’s page. If students have had interruptions in their education, you might hear the term SIFE associated with them, which stands for Students with Interrupted Formal Education. Interrupted schooling can contribute to slower fluency timelines and lower levels of literacy. Without strong language foundations, it can make learning another language more difficult.

“Exiting” means 100% fluent

Many states have different indicators that students are ready to “exit” language services, but this does not mean that they have reached the advanced fluency level. Usually, when students are deemed ready to exit, they are just broaching the intermediate fluency level. What does this mean for teachers? This means that every teacher is a language teacher and needs to consider the supports and scaffolds they are providing their MLLs throughout their curricula.

Literacy skills in a native language can’t transfer

As mentioned above, it takes about 7-10 years on average to become fluent in another language. What might speed this up? If students have proficient literacy skills in their native language(s), this understanding can help unlock another language. For example, they might understand how language functions, and know how to follow certain rules. The rules might be different, but understanding a language system and how it works is transferable knowledge.

It takes longer for older students to learn a language

It is a myth that older learners are not as competent at learning a language as younger learners. This myth is centered around the language that we hear. Younger students might feel more comfortable taking risks and producing verbal or written language more quickly, while older students might take a bit longer to demonstrate their learning. It is also important to note that older students — those who are around 13+ years of age — are more likely to retain their accent when speaking. This might make older students feel less confident or comfortable speaking, and talking with students about their accents and challenging the stereotypes about accents in our classrooms can help our older learners feel safe to take language risks.

You need a certification to support your MLLs

If you are new to language learning and want to serve your MLLs to the best of your abilities, we highly recommend checking out the work of Stephen Krashen and Jim Cummins, which is linked above. Need something to start with tomorrow? Here are some actionable steps you can take: Make your content comprehensible. You can do this in a variety of ways, but an easy way to do this is to use visuals. In my classes with MLLs who spoke three different native languages, rather than attempting to translate everything in those languages, I used pictures. I embedded videos. I had students create visuals for vocabulary words. This is something educators can do quite easily, and it has an incredible impact. Contextualize language. Think about how to show students when and where they might use this language. You can provide sentence stems, have students act out the language in short role plays, or attach physical movements to certain words. This also looks like providing a rich language environment, whether it’s encouraging discussion, think-pair-shares, or providing labels for students both in the classroom and within content instruction.

Shifting your mindset

At the end of our episode, we spoke about shifting our mindsets when it comes to our brilliant MLLs. I brought up a tweet I saw:

I think this ultimately comes down to a first language. For example, a native English speaker who is learning Mandarin and Spanish is seen very differently from a native Spanish speaker who is learning English. There are other biases that come into play, but that’s an article for another day. For now, I encourage educators to acknowledge that knowing multiple languages is an asset, not only for our students, but for our communities.

Five ways to frame care and appreciation in your professional partnership.

How do you like to receive care? What makes you feel appreciated in a partnership? When you want to show appreciation for someone, how do you communicate that?

These questions are often posed in the context of romantic relationships, but they are just as important to ask in the context of our working relationships with our teaching colleagues. Investigating the ways in which we like to receive and express support in a relationship can be especially valuable in the context of co-teaching partnerships, as humorous as that may sound. Teachers navigate high expectations and, often, high-stress situations on a daily basis. We support one another, forming community and connections through meaningful relationships. With that said, we all have different preferences and needs when it comes to how. In a romantic context, a common way to explore these preferences is the theory of five love languages, a concept proposed in Chapman's book The 5 Love Languages (1992). Chapman researched patterns in couples he was counseling and realized that many couple’s points of contention derived from a fundamental misunderstanding of each other’s needs: namely, how to receive and express affection. And so, he proposed the idea of five different love languages, paraphrased briefly below:

Caring for your co-teacher

One pathway to learn how to better support your co-teacher is to consider each other’s “love languages” in a school context. Let’s look at some examples of what these five love languages might look like in a co-teaching relationship: Words of affirmation: After a lesson, complimenting something that your co-teacher did particularly well, like asking thought-provoking questions of students or circulating the classroom consistently. These could be verbal or written comments that express your gratitude or valuing of your colleague. Quality time: During co-planning meetings, focusing only on each other and the agreed-upon task at hand; not opening or discussing emails, text messages, calendars, or other lists of tasks that must be completed at a later point (unless there is an emergency). This is always a good norm, but can be especially valuable to those who appreciate “quality time” as their language of appreciation. Physical touch: Agreeing upon a level of comfort with physical contact, like high-fives, fist-bumps or supportive hugs. I have met teachers who value hugs after especially long days, but I have also met teachers who don’t want any physical contact in a professional setting; everyone is different, and it’s important to respect individuals’ boundaries when considering this love language in a teaching context. Acts of service: Offering some additional support to complete necessary tasks, especially when we feel like with have the bandwidth and motivation to do so. This might look like offering to cover a colleague’s lunch duty or doing just a little bit of extra lesson planning to remove it from our co-teachers to-do list. Receiving gifts: As teachers, we don’t often have a lot of disposable income for gifts, nor should we feel expected to buy our colleagues gifts. With that said, I’ve given and received gifts from my colleagues in the form of borrowed books, shared classroom resources, and small pieces of favorite candy — often inexpensive or free gifts that communicate thoughtfulness and general support. Chapman makes the point that love languages, once identified, do not necessitate that we buy gifts every day or provide endless amounts of quality time. Life happens, relationships change, and we often appreciate more than one of these love languages in our relationships. The same reminders ring true for considering languages of appreciation in teaching partnerships.

I hope that this article serves as a silly starter to a conversation with your co-teacher about what their “language” of appreciation might be this year. Brainstorm together what each of these languages might look like in your particular co-teaching relationship and school context.

There’s no need for us to “love” our colleagues, but we can certainly benefit from developing supportive relationships within our professional learning communities. Let’s give and receive a little more appreciation this school year.

Three areas of focus for designing rigorous tasks that promote engagement and perseverance.

This article is part of our Close Up On CRSE series

“What motivates people to do hard things? Can you think of a time that you persisted in a difficult task, even if repeated efforts to reach your goal weren’t successful?”

This was a question we posed in a recent workshop as we were exploring the challenges of increasing student engagement. Why do people do hard things? In response to this question, we got a wide range of amazing responses. Educators shared examples of everything from finishing their master's thesis, to running a marathon, and even childbirth. The common factor across these and the many other examples provided was that people persist through challenging tasks when they are able to make a clear connection to a personal goal, believe that they have the potential to reach that goal over time, and seek the sense of accomplishment and pride that comes as a result of hard work. The factors that motivate students to persist in challenging tasks are exactly the same! Whether it’s practicing for a sport, exploring a special interest or hobby, or even staying up all night to get through the next level of the video game, we do hard things when the task is motivating, relevant, and gives us a sense of agency or pride.

Articulating the attribute

Centering Students: A Deep Dive into CRSE Practices outlines Rigorous Instruction as one of the five principles of culturally responsive and sustaining pedagogy. It states: “To ensure instruction is truly rigorous, teachers need to be attuned to the specific learning needs of their students and be able to design and implement a wide range of instructional strategies and materials that are responsive to these needs.” One of the key attributes of Rigorous Instruction is Embedding Intellectually Challenging and Diverse Content into curriculum, unit, and lesson plans. This means that teachers implement challenging tasks and use relevant resources that are responsive to the unique learning needs of their students. It also means that they're designing tasks and activities that are diverse, and reflect the real issues of the world in which we live today. This is important because learning occurs when students are intellectually engaged in culturally diverse and relevant content. In book Drive, Daniel Pink brings together decades of psychological research on motivation theory and helps us understand the mindset that cultivates intrinsic motivation, which leads to perseverance and pride. He outlines the three criteria of purpose, autonomy, and mastery as the keys to unlocking personal drive in adults. For students, this might look like relevant purpose, mastery moments, and structured autonomy. This sounds nice on paper, but what does it mean in the real world? How do we create these conditions intentionally for our students?

In the classroom, the first step to embedding intellectually challenging and diverse content is to design an intellectually challenging task connected to our students’ identities, interests, and instructional goals. This means making connections between our content area and critical thinking tasks that include the demonstration of higher order thinking skills, as found on frameworks like Bloom's Taxonomy, Webb’s Depth of Knowledge, or The Cognitive Rigor Matrix, which is a combination of the two. Setting an intellectually challenging task that taps into students’ ability to analyze, synthesize, or evaluate content information takes time and practice. Choosing an entry point and topic from diverse source material is a key to making the task personally relevant.

After setting the task, then we can begin creating the conditions that cultivate motivation and perseverance.

Relevant purpose

If we look back at the conditions that create perseverance through challenging tasks, we’re reminded that the common factor is people seeing the task as personally relevant to a specific goal or skill they want to achieve. So often in school, the goals we set for students are outside of their own interests. The state sets the goals on high-stakes exams, our district might set the goals for curriculum or course outcomes, and teachers set in-class goals for what students should accomplish, and why. There are almost no formal structures for students to engage in the process of determining what they want to learn, and for what purpose. While there are real constraints that we’re working with when it comes to content standards, there are many opportunities to tap into students’ interests, and to create relevant purpose for the tasks we ask students to engage in.

Mastery moments

Creating mastery moments means that as we look at our arc of instruction throughout a lesson, a week of lessons, or a unit plan, we identify key moments of the learning process and identify those as micro-targets or mini-goals along the route. Creating some built-in celebrations or rewards for hitting these targets inspires a growing confidence and positive pride that comes from meeting a goal.

Structured autonomy

Autonomy is the ability for a person to choose their own process. Students may not have developed all of the skills needed to stay productive with unstructured autonomy, but structured autonomy is empowering and cultivates skills to help students learn how they work best. Structured autonomy means creating pathways that maximize student choice, preference, and independent work with increasing time on task.

When it comes to student engagement, in an effort to create student-friendly tasks, we often associate more engaging with easier. We don’t want our students to struggle or get frustrated during the learning cycle. But easier isn’t necessarily engaging — and it rarely builds the critical thinking and content knowledge that students need to motivate them to take on the next learning challenge.

Embedding intellectually challenging and diverse content into curriculum is critical to engaging students in a productive learning experience that is equally intellectually challenging and engaging. We can all do hard things when we see the purpose, own the goal, and believe that our success is possible.

Navigate reading mastery and the science of reading to create meaningful instruction for young readers.

This is the first installment in our Science of Reading series

In the realm of reading instruction, fluency acts as a foundational cornerstone, shaping the way readers interact with written language. Often hailed as the bridge connecting decoding and comprehension, fluency plays an instrumental role in molding a reader's overall understanding. This article takes a comprehensive look at the concept of fluency, delving into its significance, practical implications, and its alignment with the science of reading, with a particular focus on the role of guided reading.

Defining Fluency: Beyond the Basics

Fluency in reading goes beyond just being able to read words correctly. It involves reading in a way that is smooth, precise, and with expressive intonation. It also includes accuracy in understanding the text, maintaining a suitable reading speed, and paying attention to prosody, which refers to the rhythm and melody present in language. When all of these elements come together, they transform reading from a basic recognition of words into a skill that allows you to effortlessly comprehend the deeper significance of a text.

Why Fluency Matters: Bridging Decoding & Comprehension

Fluency acts like a bridge that connects two important parts of reading: decoding and comprehension. Decoding is the process of breaking down written symbols into recognizable words, while comprehension involves understanding the true meaning of the text. When a reader becomes fluent, it means they can decode words effortlessly, which in turn frees up mental energy. This newfound mental capacity can then be directed towards better understanding the content of the text. Research has shown a strong connection between fluency and comprehension. Readers who have developed fluency are not only able to grasp complex ideas easily, but also engage in critical analysis of the text. This skill in turn helps them develop a genuine fondness for reading. This dynamic relationship between fluency and effective reading instruction is a central focus within the science of reading.

Guided Reading: A Path to Proficiency

In the array of strategies aimed at promoting fluency, guided reading emerges as a standout approach. Within a guided reading context, small groups of students engage in shared reading experiences, guided by their teacher. The strength of guided reading lies in its ability to:

Guided Reading in Action: Effective Approaches

Elevating Fluency: A Reading Journey

Fluency goes beyond a mere skill; it's the foundation of satisfying, meaningful reading. Guided reading plays a key role in nurturing this skill, supporting capable readers, and fostering a genuine passion for reading. As educators embrace the principles of guided reading and other fluency-centered approaches, they empower young minds to confidently navigate texts. This involves actively connecting and interlinking various elements within the text, much like weaving threads into a fabric. This journey blends the art of reading with the science of effective reading instruction, resulting in a community of skilled and enthusiastic readers. If you are interested in exploring guided reading further, join me at Best Practices for Guided Reading, which will provide you with an opportunity to experiment with designing and implementing guided reading lessons of your own!

Four pieces of advice to keep in mind as you settle into your classroom.

Dear Math Teachers,

I hope you’re entering your classroom rested and relaxed. I am going to start this letter by thanking you. Thank you for everything you have done in your previous years of teaching. Thank you for everything you will do this year. If you are open to it, I would like to share some advice with you as you continue to navigate what works best for your students this school year.

Come to peace with lack of time

I want you to remember that you will never have enough time, and that is okay. We allow time to really grab hold of us, tangling us in a sense of urgency unfulfilled. I see teachers stress so much about time; not enough time to cover all the content, not enough time to do this fun activity, not enough time to explore something students care about. Find a way to accept that you will never have enough time and free yourself from this immense pressure.

Embrace curiosity

Curiosity was what made me fall in love with math; I always wanted to know why something worked. Unfortunately, we are so stressed about covering as much content as possible that in math classrooms we are often ignoring our curiosity. If a student has a question or wondering, stop the previous plan and engage in it. Did a student come in talking about a car they really like? Let’s learn everything we can about this car. How fast does it go? How did they figure that out? How much would it take me to save up to get it? Is the price of the car unreasonable? What about student’s favorite musicians — how much do we think they make? How do they use patterns to make their music? The best way to prepare a future mathematician is to grow their curiosity; take advantage of every opportunity to do this in your class.

Find your community

Teaching can feel isolating to many lately. Find a community that sustains and supports your practice. It doesn’t even have to be in your school; community can take on many forms. Find some accounts of math teachers on social media that are interesting or inspiring to you. Subscribe to some websites that have shared resources you enjoy. I learn a lot from the newsletters and resources at YouCubed and Math Medic. I also love following Howie Hua. Find those who make you feel seen and inspired.

Make room for joy

Take a moment to think about what brings you joy. Ask your students what brings them joy. Now add those things into your class. Dance to music with your students. Make silly jokes. Play games. Gholdy Muhammad in her recent book, Unearthing Joy, says “Joy is the ultimate goal of teaching and learning, not test prep or graduation.” The lessons we truly learn, the moments and memories that we never forget, are centered around joy. We have to make sure we have room for them in our lessons.

I am excited for the journey you and your students are embarking on in your math classroom. Let go of the stress of time, fumble through curiosity, find your people, and have so much fun.

Keep up the great work! You’ve got this! With lots of love and support, Victoria

Amplify small group instruction and strategic student grouping with this interactive approach.

Three years ago, we were quickly shifting our classrooms to online platforms as instruction was going remote for an indefinite amount of time. We tried to keep teaching throughout the pandemic and survived the snafus that happened throughout the day. (Remember that time you thought you were muted, but you weren’t? Bleh!) Our learning curves for online teaching grew exponentially, and many of us have incorporated the most promising practices into our classrooms today, such as using Google Docs for group projects or editing and commenting on a student paper in live time.

Although there is an educational app for just about everything, we suggest resisting the urge to default back to solely online learning (even while in person), and instead consider the unique benefits of being together in time and space. Let’s design opportunities for students to collaborate, and embrace the physical classroom by creating learning opportunities that take students away from the Chromebooks and into a live setting. Characterized by movement, interaction, and small group learning, station teaching is one of the six established co-teaching models that takes advantage of being together within the four walls of a classroom. As with all models, station teaching comes with its own unique benefits, challenges, and logistics — let's walk through this method in an effort to support you and your co-teacher in planning and facilitating this meaningful approach to learning.

What is station teaching?

Station teaching is when content and instruction are divided into distinct components or strands. Students are divided into equally sized, typically heterogeneous groups. Each teacher teaches a specific part of the lesson/content to different groups of students as they rotate between teachers. Students also rotate through center(s) where they complete an independent task.

What promises does this model offer?

Station teaching provides an opportunity for smaller group instruction and strategic student grouping. One of the more obvious benefits of station teaching is that teachers have an opportunity to work with a small group of students, thus allowing for more responsiveness to individual questions, preferences, and needs. Stations also allow us to leverage the benefits of strategic student grouping, where teachers are intentional in the way that students are grouped together in service of the learning goal. Typically, heterogeneous groups, in which students with a variety of learning traits and needs work together, work best for the station teaching model; at the independent stations in particular, students have the opportunity to learn from and teach each other. Station teaching allows for exploration of a topic or skill through multiple perspectives, entry points, and modes of expression. In Universal Design for Learning (UDL), a framework designed to ensure that all learners can access and participate in meaningful, challenging learning opportunities, one of the guiding principles is that learners differ in the ways that they perceive and comprehend information that is presented to them. Therefore, it is essential that teachers provide students with multiple means of representation of content. Stations easily allow us to provide representation of a topic in multiple ways; each station could focus on a different text, visual, or audio source. Similarly, each station can allow students to express their learning through a different medium or modality; another important principle of UDL. Station teaching allows the opportunity for natural “brain breaks” and movement. Research has shown that regular, short breaks in the classroom can help students increase their focus and reduce stress. With shorter “chunks” of academic engagement and clear, natural transitions between tasks, the station teaching model inherently incorporates breaks for students. The time it takes for students to travel to the next station could be leveraged to provide students with the physical or social engagement they might need to sustain focus: perhaps you play a song that students enjoy, or invite them to do a particular stretch. Station teaching can help strengthen a co-teaching relationship by providing the opportunity for shared ownership of planning and facilitation. Anyone who has co-taught before knows that it can be difficult to find a groove in which both teachers are easily and equally sharing the workload of lesson planning and facilitation; obstacles like lack of common planning time, unclear goals, and difference in teaching styles and preferences can often get in the way. If you and your co-teacher are finding yourself in a stage of your team development in which roles feel lopsided or undefined, a stations lesson can be a helpful way to help redistribute some responsibility. The ways in which content and instruction are divided in station teaching offer a clear path for delegating planning and teaching duties; each teacher can be responsible for the designing and facilitation of one station (with coordination and communication, of course!).

What are some potential pitfalls?

Noise level and space limitations can create challenges. With several groups of students working on different tasks simultaneously, some students (and teachers!) might find the level of noise and movement in the room to be an adjustment. Preparing students for this might be helpful; you might say something like, “Today’s class may be a bit louder than our typical class, but there will also be quiet moments at the end of the stations so you can collect your thoughts via writing.” It’s also helpful to think strategically about where each station is set up in the room; having the two teacher stations as far away from each other as possible is often the way to go, since teachers often have the loudest voices in the room! Careful attention must be paid to pacing. In contrast to learning centers, where students are moving between learning engagements at their own pace, station teaching is often characterized by coordinated rotation, where everyone moves on to the next station at the same time. This means that all stations need to take roughly the same amount of time, which can be challenging to anticipate in planning. All stations should have flexible tasks that can be shortened or extended with enrichment options or additional discussion questions, depending on how quickly a particular group engages in them. Not all content is well-suited for stations. One of the trickier dynamics of station teaching is that not all students will begin their learning in the same place; some will begin at the independent station, while others will begin at the station led by co-teacher A, while still others will begin at the station by co-teacher B. Because of this, it’s important that the topics or tasks at each station are non sequential — that one station is not a necessary prerequisite to engage with another. Therefore, stations are not ideal for topics or skills that require a specific or strict sequencing of tasks or texts. It’s also not ideal for tasks that require deeper and more sustained investigation or attention, since time spent at each station is relatively brief compared to a full class period. Rather, stations work great for topics that are broad with multiple strands, perspectives, or approaches, or for introductory explorations or final reviews.

How can independent work be structured?

Recent research has highlighted the benefits of letting kids do things on their own, and station teaching offers the opportunity for practicing independence. We have generally found independent stations should be built on familiar territory: a concept, graphic organizer, or task directions that students have seen before. Be sure to have all of the supplies ready at the independent station, and try not to overcomplicate the directions (this sounds obvious but can be challenging)! Here are just a few ideas for independent work:

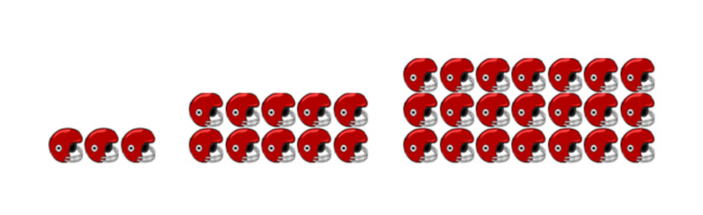

What can this model look like in action?

Given the promises and potential pitfalls of this co-teaching model, we can determine the kinds of lessons and learning objectives that will be best suited for this instructional approach. Here are a few examples: 3rd grade ELA Students engage in stations that support them with the skills of determining the main idea of a text. At one teacher-led station, students are creating titles for chunks of text. At the second teacher-led station, students are reading a short text and asking: what is this story mostly about? At the two independent stations, students are sorting pictures into categories, or listening to an audio book and answering multiple choice questions. 7th grade Math To begin a new unit, students are engaging in an opening inquiry around the question: Why are surface area and volume important concepts in everyday life? At one teacher-led station, students make observations about water displacement when an object is dropped in a glass of water, and make predictions on whether the tray will be able to catch the displaced water; at another, students are tasked with wrapping a present; at another, they must choose the best tupperware container for leftover “food.” After visiting all the stations, students reflect on the guiding question and discuss with their peers. 11th grade US History Historians often teach an era through a variety of lenses, such as the culture, the key events and figures, and the different perspectives of an era; this approach lends itself easily to a station lesson. When studying the Progressive Era, for example, students can investigate: How did the growth in industrialization and urbanization lead to positive and negative changes in American society? At one teacher-led station, students can look at images from the time period (from photojournalists such as Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine) and notice the subjects and stories these photographers may be trying to tell about urban life in the early twentieth century. At an independent station, students can define key terms, such as “muckraker,” “progressivism,” “industrialization,” “modernization,” and The Gospel of Wealth. Students can look up these terms and record what they learn in the form of Cornell Notes or a Frayer Model. At another teacher-led station, the teacher can facilitate a reading of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle or The Story of Ida B. Wells, and ask students to make meaning of the text, and take notes on what the text conveys to the reader. After visiting all three stations, students can compare their notes and discuss the positive and negative impact of industrialization and urbanization during the U.S.’s Progressive Era.

The devil is in the details

The more you and your co-teacher can plan in advance for the logistics of station teaching, the more successful your lesson will likely be. How long will students spend at each station? How long will they be given to transition between stations? Which teacher will be responsible for keeping time and cuing the students? How will students know where to go next? (We suggest a slide or poster indicating the direction of rotation for that one!) Preparing all the materials in advance and having a clear and brief set of directions at each station is crucial (particularly at the independent station).

Practice pays off

While this article details the logistics of station teaching with an eye on co-teaching, we cannot overemphasize the importance of designing opportunities for students to interact with each other and with the physical space of the classroom in all classrooms. We know that students missed years of face-to-face interactions due to the pandemic; we suggest being proactive and creating moments for students to embrace a shared space and interact with each other in a low-stakes way. With all these dynamics and logistics, your stations lesson might not go perfectly the first time; don’t give up! We encourage you to reflect on the challenges, tweak it, and try it again. Stations might be a bit of a learning curve for your students as well, but as with any classroom protocol or routine, station rotation and engagement are skills that can be explicitly taught, scaffolded, and practiced. It’s our opinion that the work pays off, as we’ve found this approach to be an interactive and engaging way to punctuate particularly compelling topics in a curriculum.

Four ways to cultivate student connections through stories, personalities, and interests.

It’s the first few weeks of school. New students are entering our school’s hallways and sitting in our classrooms. Fresh paper, pencils, and (hopefully) charged computers are perched on desks. Awkward glances and shuffling feet and uncertain pauses fill the air. As teachers, we are faced with this challenge: how do we begin to build a learning community in our classroom, one that invites trusting dialogue and encourages intellectual curiosity?

I often received one, seemingly simple answer: “find a good icebreaker.” An icebreaker is an activity or engagement task designed to get people talking and learning about one another — in other words, a task to “break the ice” of social awkwardness. A fellow teacher in my school swore by “Would You Rather?” as the icebreaker that had withstood the test of time, asking students to answer a series of extreme either-or questions like, “Would you rather fight a bear or a shark, and why?” I don’t think there’s one best icebreaker for all students or for all teachers. It’s difficult to know definitively what will resonate with your particular students. With that said, I knew that it was possible to find an icebreaker that invited students to get to know each other in a meaningful, personal way. Below you’ll find four activities that will help you “break the ice” with your new students and begin creating genuine connections within your classroom community.

The Neighborhood Map

Discovering & Writing About a Memory This first activity, invites students to make a memory map of their childhood bedroom, apartment, house, or neighborhood. Then, it asks students to look for stories they can share, inspired by places marked on their map. The memory map was developed by Stephen Dunning in the early 1970s and later articulated in his book Getting the Knack (1992). His workshops led to other educators across the country creating various versions of this practice, including by members of the South Coast California Writing Project. Ask students to draw a birds-eye view map, then “walk” a partner or small group through descriptions of the places on their maps. After doing so, students number and label these “story places” on their maps and choose one story to write about further. Students are invited to share their written story in a partnership or in a small group. For younger students, I encourage using some sentence starters to scaffold the sharing process, such as “This place stays in my mind because…” or “The important thing about this story is…” A possible set of directions are included here and here, but I encourage you to develop directions that will work best for you and for your students. For those who may not feel comfortable drawing their own memory map, perhaps imaginative or fictional map drawing could accomplish a similar goal of learning about your students. If writing is a central component of your classroom, consider transforming this activity into a writing benchmark for your students at the beginning of the year to gain insight into their writing abilities. This activity can work in an elementary, middle, high school, college, or even adult-education setting, and is especially inclusive for English language learning students, given the opportunity to tell stories through drawn visuals.

The Cultural Tree

Getting to Know Yourself and Your Students In this activity, students are asked to create a “cultural tree” that represents their culture. Originally envisioned as part of Zaretta Hammond’s work in Culturally Responsive Teaching & the Brain, the drawing of cultural trees asks students to identify three levels of their culture: surface level — aspects of culture you can see like food and dress, shallow culture — aspects less explicit, like concepts of eye contact and personal space, and deep culture — unconscious beliefs and norms like concepts of fairness and spirituality. My colleague at CPET, Lauren Midgette, has used Hammond’s work to write and to reflect on the possibilities it has for getting to know students, but also ourselves, better in the classroom this school year. Midgette makes the point that the drawing of cultural trees — and the discussions inspired by them — provides a healthy soil to help our students grow. Each level of culture — surface, shallow, and deep — is visualized on the tree as leaves, trunk, and roots, respectively. For younger students, I don’t think the framing of the tree as “cultural” is necessary for the activity to be an effective tool for discussion. Students could certainly label a tree with aspects of who they are that are surface (easily seen by others), shallow (not as easily seen), or deep (entirely unseen).