|

Envision how you can cultivate clear communication and cohesive leadership across your community.

Building a cohesive community in large public schools, often with over 2,500 students and 200 staff members, presents unique challenges. Fragmented communication and a lack of understanding of roles can hinder unity and the effective implementation of initiatives. However, leveraging the leadership team to clarify roles, expectations, and prioritize students at the center can foster a stronger community.

How can we do this? What might it look like? Case study: navigating change & complexity

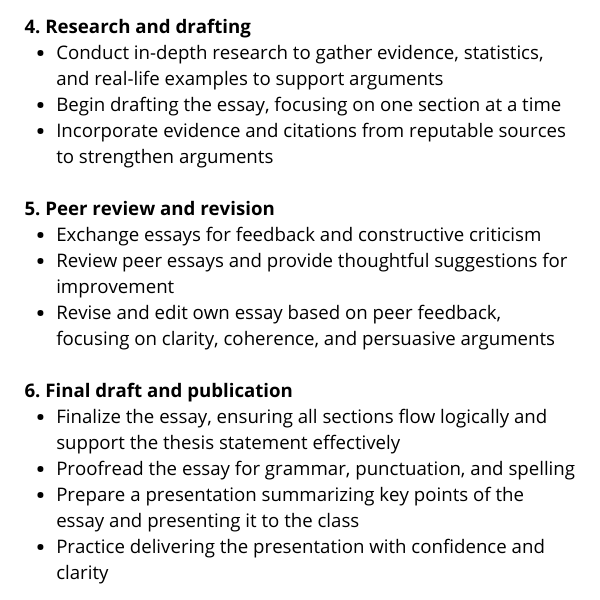

In my eight years working with a large public school in Georgia, I've seen firsthand the difficulties in maintaining cohesion amidst frequent changes in administration, leadership, and student demographics. Despite well-intentioned systems and structures, the key issue often lies in the communication and understanding of expectations across the school.

For example, at the start of the school year, a new administrator joined the team, and introduced a new unit planning template aimed at enhancing differentiation for ELL and SPED students and using data to improve instruction. However, teachers were frustrated by the lack of clarity and timing of the rollout. It wasn't the plan itself, but rather the manner and timing of its introduction — amid numerous other mandates — that caused frustration. As a result, I worked with the teachers over the course of a day in late August, to unpack and make sense of the unit plan and how it could support them in facilitating their professional learning communities and use data to inform instruction. Furthermore, the departure of three seasoned instructional coaches led to the formation of essentially a new team, underscoring the necessity for community-building and standardizing approaches. Thus, on the second day of my visit in August, I collaborated with the coaches to articulate the team's mission and vision, and to devise coaching plans to address specific departmental goals and challenges. This collaborative effort aimed to empower the coaches by instilling in them a sense of purpose and providing clear direction. As I concluded these two days, I felt a sense of achievement, armed with a well-defined plan and next steps. Addressing confusion: building a unified front

Upon returning in February, however, I encountered more changes and more confusion. A new instructional coach had been added to the team, requiring onboarding and community building. Additionally, a coach expressed uncertainty after participating in a co-teaching session with one of her teachers, recognizing its potential as a powerful support model, but questioning whether it fit within the scope of her role. And another coach wanted to restructure PLCs but was uncertain of administrative approval. This confusion showcased a disconnect between administration, coaches, and teachers.

Leadership retreat: a strategic approach

What became apparent to me was the need to strengthen communication and understanding across the school. The lead instructional coach — a seasoned and reliable figure within the school — and I collaborated to reach out to the principal. Together, we arranged a leadership retreat with the aim of addressing these challenges.

We worked side by side in planning the retreat, focusing on the following objectives: 1. Engaging key stakeholders Based on my conversations with teachers and teacher leaders, there was an overwhelming number of meetings taking place, many of which felt unnecessary and unproductive. This also contributed to confusion as the information trickled down from person to person, risking various interpretations and varying implementations. We wanted to reduce this risk by ensuring essential stakeholders — principal, APs, instructional coaches, and department chairs — were present at the retreat, to share perspectives and make informed decisions. 2. Building community and fostering relationships Large schools make it harder to feel connected across the larger number of teachers and leaders. The retreat was intended to be an opportunity for leaders to connect personally and professionally, fostering trust and shared responsibility. 3. Establishing priorities It became clear to me that the principal and his cabinet knew what the goals of the school were, but not so much the other leaders across the school. The retreat aimed to establish clear goals and priorities, ensuring alignment across the school leadership. 4. Clarifying roles and responsibilities Based on different conversations I was having at different times, it became clear that there was confusion around roles and responsibilities. Reflecting on and understanding each leader's role helps reduce confusion and aligned efforts. For the retreat, we wanted to focus on questions like: How do I understand my role? Does this align with my desires/hopes for this role? How does my role compare, support, and/or overlap with others in the school community? 5. Planning for the future One of the pitfalls schools face is too many priorities and initiatives, which can result in feelings of failure and overwhelm. This was the case at this school. We wanted leaders to work on and ideally establish the school calendar together to ensure there was enough time and space for these initiatives to thrive in the subsequent school year. We wanted to ask questions like: What do we need to plan for now to implement successfully in the coming school year? Who is responsible for these various initiatives and how will we monitor progress? I just recently debriefed the retreat with the lead coach. Overall, she believed the retreat was a success, leaving participants with a clearer sense of purpose and responsibility. Additionally, she believed it strengthened relationships and understanding of day-to-day roles. Promising practices for all schools: a blueprint for success

Although this article centers on a single school, it highlights several promising practices that can benefit schools of any size. I see the potential for these strategies to be valuable for any organization and its leaders.

By adopting these practices, schools can enhance connection, understanding, and ultimately support the most important goal of all — advancing our students.

Possibilities for encouraging inclusive discussions and perspectives in the classroom.

We are a prideful household. We’ve marched in Pride Parades and have enjoyed Drag Queen Storytime. We have a rainbow flag displayed in our front yard, and my kiddo knows that every person is unique and beautiful. My partner and I have made intentional decisions, and sometimes, we have faced adverse reactions. For example, when my child was six months old, I posted on social media a new book I purchased for our library in honor of Pride Month: The GayBCs by M. L. Webb. I immediately received some “feedback,” mostly different ways to say my kiddo was too young to learn about “gayness.”

This is not dissimilar to some of the comments I received as an educator. In an effort to ensure my curriculum was inclusive, I had parents contact me concerned that reading a text with gay characters would give their students “ideas.” Because of these experiences, I am no stranger in attempting to both quell concerns and challenge some of the hurtful stereotypes and assumptions about sexuality. Below, you will find example responses to some of these comments, but also a list of texts that I have used to encourage positive conversations that allow students to consider how they create more welcoming and affirming spaces. When the conversation starts with a hurtful comment

"You don’t know if [so and so] will be gay."

You’re right, I don't. But right now, they have gay friends, neighbors, community members, and I believe that we should recognize the inherent worth and dignity of every person. I want our community members to know they are loved for who they are and not "in spite of" being different. “You’re going to turn [so and so] gay.” I assume the person asking this is heterosexual, and so I begin with a question: How did you know you were straight? The usual answer is, "I don't know, I just knew." I follow up with, Do you think someone could make you change your sexual orientation? Usually, they respond with no. If they take into consideration that they “just knew” they were heterosexual and they don’t think someone or something could make them change their mind, then what makes them think people who aren’t heterosexual learn it? Sometimes it might take someone a bit of time to figure out who they are attracted to (if anyone at all for that matter), and that is okay. “They don’t need to learn about sexual orientation at a young age.” I always find this comment a bit funny; I wonder if the people who make this comment realize that heterosexuality is a sexual orientation! When it comes to a man and woman being in love, kids see representations of this everywhere: books, television shows, and other forms of media. They learn that a man and a woman can love each other, so why can’t they learn that humans are capable of loving outside of this binary? “It’s not important to learn these terms so young.” On the contrary. If my child is a part of the LGBTQIA+ community, having the language and confidence to express who they are and who they love from an early age can decrease feelings of estrangement, and providing them with the language at an early age assures me that they can talk about who they are with pride at any time in their life. If they are heterosexual and cisgender, they will need this language to advocate for their LGBTQIA+ community members because as I said before, we are a prideful household. When the conversation starts with you

If you’re a parent or an educator looking for ways to diversify your library and start some inclusive conversations, here are some books I recommend as a mom and a teacher:

At the end of the day, our goal is to create welcoming spaces, whether that’s at home or classroom, for all. This article offers resources and ways to introduce inclusive language particularly for young children, and those conversations can mature and gain complexity alongside them to reflect even more nuance. I do recognize that this post doesn’t even touch upon the gender spectrum, transgender folx, and the many different ways people love. But it’s a start.

Let’s learn together, taking the steps we need to make our world a more inclusive place.

Release the expectation that questions must be followed by answers, and instead position questioning as a key part of the learning journey itself.

On a recent episode of our Teaching Today podcast, Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang and Dr. Cristina Compton are in conversation with Dan Rothstein, Luz Santana, and Sarah Westbrook from The Right Question Institute, an organization founded on the belief that when people of all ages learn to ask the right questions, it leads to feeling a new sense of agency, confidence, and power. In particular, they talk about the power of the Question Formulation Technique (QFT), a structured method for generating and improving questions.

In its simplest terms, facilitating the QFT means walking participants through the process of producing questions, improving questions, strategizing around their questions, and reflecting on what they learned. To start, participants are given four rules for producing questions around a selected focus:

Then, participants work to improve questions by identifying questions as open-ended or closed, reflecting on the advantages of each type, and experimenting with changing open-ended questions to close-ended questions, and vice versa. Strategizing around questions means participants identify the questions they find most important, and consider what they would need to know and do in order to work towards answers. Finally, participants reflect on what they learn throughout the process. Recently, I utilized the QFT in a whole school PD at one of our partner schools in the Bronx. In a recent round of classroom visits, the school leadership team had noticed a trend: more often than not, lessons lacked closure. Students would be in the middle of a learning activity when the bell would ring and they would need to pack up and move to their next class. I wanted to use the QFT as a way to launch this new PD topic. It was really interesting to listen to the episode in light of this experience. Here, I share five big ideas from the episode and reflect on their connection to my recent facilitation of the QFT, in hopes of bringing them to life with examples from the field. “While we worked with families, very often they said that they were not going to the children’s school and they were not participating because they didn’t even know what questions to ask. So they gave us an idea that asking questions was a big need.”

At the beginning of the podcast, Luz shares with us the origin story of the QFT — how her and Dan’s work with families connected to a dropout prevention program in a low income community north of Boston inspired them to work on development of the skill of question formulation.

Since so much of the mission of The Right Question Institute seems to be about empowering students in asking their own questions, I share the surprise that Cristina expresses about the fact that the strategy was actually born from work with adults. But upon further reflection, it makes sense. In Malcom Knowles’ six assumptions of adult learners, he stresses the importance of intrinsic motivation, or the idea that “adults learn best when motivated from within, not from incentives or other external influences.” Letting teachers drive the inquiry and steer the direction of the learning is crucial to intrinsic motivation, and the QFT is one possible and powerful lever for doing so. Relating back to my own experience, this point felt particularly salient for a topic like lesson closure — which, I think most would agree, is pretty dry on the surface. It felt especially important to consider how to engage teachers in a way that felt authentic, beyond basic compliance. “ [An] indicator you’re doing it right is that there’s divergent thinking that’s happening, there’s convergent thinking that’s happening, and there’s metacognitive thinking. And those are the three core thinking abilities we feel are sort of part and parcel of what the QFT is and does.”

I’ll admit that when Cristina asks the panel a question about fidelity and what it looks like in relation to the QFT, I got a little nervous. In my PD session, I did not follow the QFT “to fidelity” in the sense of strictly adhering to the four steps that they outline. Rather, I took it upon myself to make some tweaks based on my content, audience, and purpose. For example, I didn’t have teachers change questions from closed to open, or open to closed; I thought our limited time would be better spent trying to categorize the questions into themes.

So, I was heartened to hear how Sarah and the team were defining fidelity partly as the presence of those three types of thinking: divergent thinking, or “that really creative, generative thinking that happens when you first produce questions,” convergent thinking, which happens when “you’re working on the form of your question or when you’re prioritizing,” and metacognition, or “thinking about your thinking, which happens all the way through.” According to this definition, I think my adaptation of the protocol could still be considered faithful to the spirit and purpose of the QFT. This definition should also empower other teachers and facilitators to make the protocol work for them. “It’s fascinating to think about students’ questions as a formative assessment…it’s just an extraordinary resource to hear what they are asking about without you telling them what you should be thinking about.”

Dan’s point that the QFT can serve multiple purposes — formative assessment being one of them — really resonated with my facilitation experience as well. When the school’s principal shared that this was an area of growth for teachers, I trusted her assessment, but knew I didn’t have the full picture. I immediately began posing questions of my own: what was preventing teachers from closing their lessons? Was it a lack of conviction in the importance, a lack of concrete strategies, or something else I couldn’t have anticipated? The themes that emerged from their questions (many around the challenges of pacing) helped to steer the direction of the inquiry cycle to directly respond to their interests and needs.

“You could go through the whole QFT and never answer a single question that’s posed. Rather, it’s about curiosity. It’s about looking at something from multiple perspectives.”

In summarizing some of the conversation, Roberta reflects on how the QFT “flips the script” on traditional learning in a few crucial ways, not only in terms of who is asking the questions, but also in terms of the purpose behind asking them — not to “fill in the blank” but as a way to embark on a learning “expedition.”

When I returned to the Bronx the week following the QFT to continue the learning series, the school’s principal was excited to share that she already was noticing a positive shift in teachers’ practice around lesson closure. On a surface level, this was pretty surprising; after all, we hadn’t actually answered most of the questions yet, or discussed any concrete best practices. But in light of the podcast discussion, it makes sense: The questions themselves become the learning, or at least a large part of it. “One of Luz’s pieces of advice that I also keep in mind is that you have to put on your thick skin. Sometimes it doesn’t work perfectly the first time.”

Here, Sarah reminds us that when trying the QFT for the first time, or in a new context, we have to tolerate the messiness of learning, recognizing that both facilitation and participation with any new protocol or strategies requires some trial and error, as well as multiple opportunities for mastery.

I want to highlight this point, so as not to misrepresent my facilitation experience; while it was mostly positive, there were also some challenges. Teacher feedback suggests many, if not most, of the teachers found the PD session engaging and understood its purpose. Still, one teacher shared their frustration that the session was “focused on the problem” and not the solution. To me, this feedback highlights Roberta’s point that this way of engaging with a topic is a paradigm shift; when we enter a space as a learner, we expect to be given answers. But it also highlights for me the need as a facilitator to be even more explicit about the fact that protocol represents the beginning of a learning journey and not its entirety. Furthermore, as Luz suggests, I returned to the teacher-generated questions in subsequent sessions to make their connection to our work clear.

How one school's teacher leaders are cultivating curiosity and creating a roadmap for meaningful change.

In a recent professional development session at a high school in Georgia, I aimed to enhance a group of leaders' understanding and use of inquiry in their practice. Guiding teacher leaders through an exploration, I encouraged them to reflect on the everyday significance of inquiry within their professional roles, emphasizing its promise in driving practical growth and development. Together, we engaged in a reflective dialogue that included delving into the process of inquiry, unpacking its intended purpose, and highlighting its importance in fostering a culture of continuous improvement within the school community.

The importance of inquiry

What exactly is inquiry, and how does it enhance the work of teacher leaders? Inquiry, simply put, involves deepening understanding through curiosity, questioning, and seeking answers, supported by data analysis. It serves as a means for collaborative exploration, enabling educators to address shared challenges, develop effective strategies informed by data insights, and monitor progress towards common goals. Through this process, teacher leaders not only enhance their own practice, but also foster a culture of evidence-based decision-making within their school communities.

Central to this exploration are inquiry teams, which consist of professionals coming together in their quest for understanding and improvement. These teams operate based on the principle of intentional collaboration, prioritizing issues relevant to their roles and responsibilities. This approach ensures that inquiry projects remain manageable and grounded, enabling teams to achieve tangible outcomes. Moreover, it cultivates a culture of shared responsibility and commitment, fostering an environment that promotes collective growth and progress. Navigating the stages of inquiry

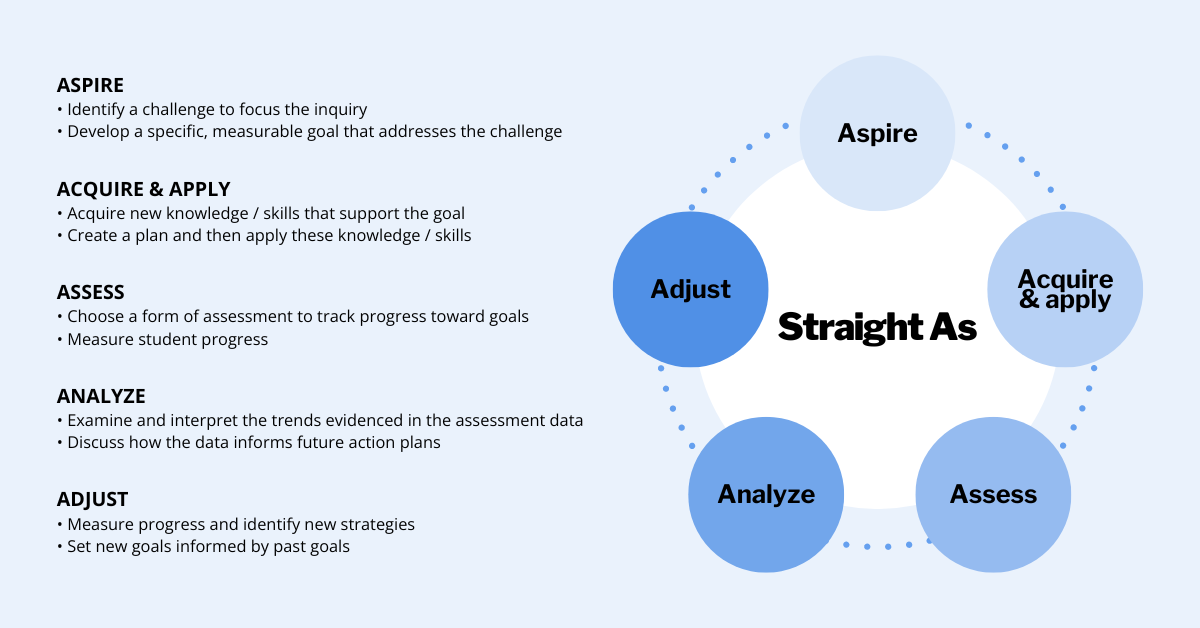

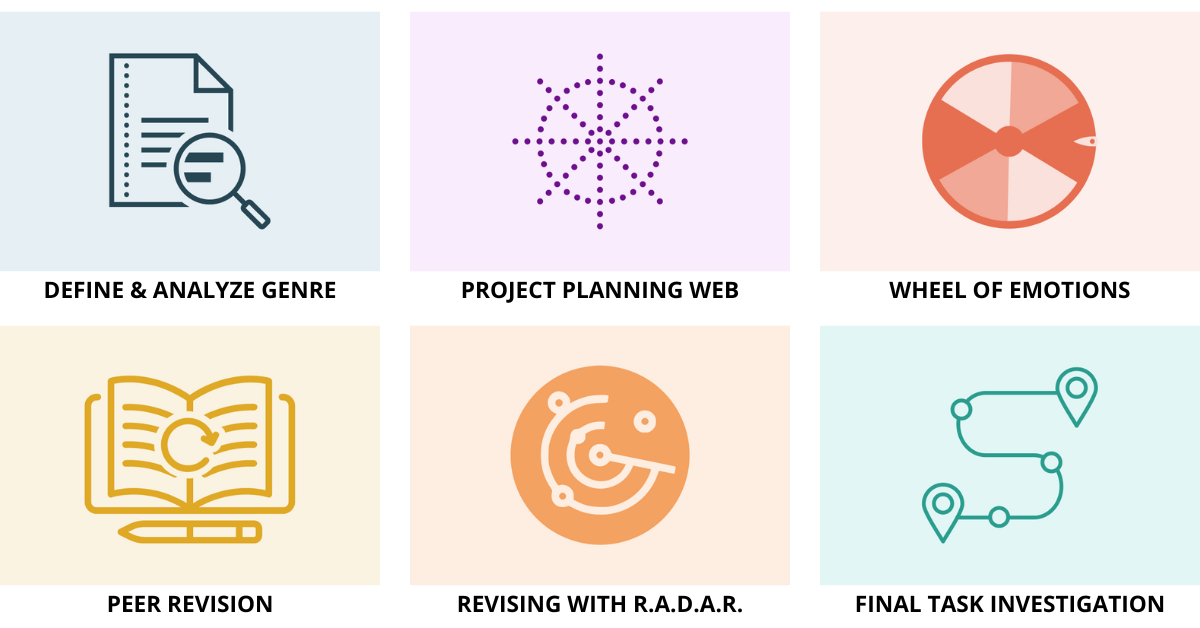

One notable framework that supports inquiry with teacher leadership is our Straight As protocol. This serves as a structured approach for navigating the stages of inquiry, guiding educators through a systematic process of goal setting, knowledge acquisition, assessment, analysis, and adjustment.

Our initial session in Georgia was focused on the Aspire stage, where teacher leaders chose to explore the challenges faced by their students and collaboratively identify SMART goals — goals that are specific, measurable, actionable, relevant, and timely. Teachers identified challenges such as stamina, confidence, literacy, Lexile levels, and more. From there, we analyzed these challenges and attempted to narrow down our list by thinking about which obstacles could be combined, as well as which obstacle(s) felt the most important, the most urgent, or were in a high-leverage area. Through a process of reflection and dialogue, each department gained a clear understanding of their objectives and a roadmap for achieving them.

During our time together, we thoroughly analyzed various SMART goal examples, focusing on key aspects, such as:

We also examined sample inquiry questions, proposed change strategies, and the anticipated timelines. This comprehensive approach aimed to equip teacher leaders with the necessary insights and tools to effectively formulate their own goals. At the end of the day, each department presented their SMART goals for feedback, fostering collaboration and refinement. As a next step, our group of teacher leaders will present these goals to their respective department teams with the hopes of further refinement and integration into a larger inquiry process throughout the semester as we continue our work together.

The process of inquiry provides teacher leaders with a practical approach to deepen their understanding, collaborate effectively, and drive meaningful change within their school communities. By embracing the principles of inquiry and utilizing frameworks like the Straight As protocol, educators can see themselves as catalysts for positive change, enhancing their teaching practices and empowering their students. Moreover, by incorporating data analysis into the inquiry process, educators can make informed decisions based on evidence, thereby increasing the effectiveness of their strategies and interventions.

Look beyond traditional forms of data to choose a co-teaching approach that aligns with your students' needs and goals.

Throughout my time as a coach at CPET, I’ve done a lot of professional development around co-teaching, and one problem I face is this: teachers, ever the committed and curious group, often want to try out whatever co-teaching approach we’re modeling and discussing right away — like in the next day’s lesson.

You might be wondering: wait, why is this a problem? And I agree — this is a pretty good “problem” to have. I am so heartened when teachers exhibit this kind of eagerness and openness. At the same time, I worry that professional development on co-teaching can sometimes be interpreted as a “bag of tricks” to try and apply at random. We must remember that not all co-teaching models are equally effective in any given situation; we must select them thoughtfully and intentionally with our specific students, context, and content in mind. Ideally, and as much as possible, we want to choose a co-teaching approach based on a) our learning goals for students and b) what our data tells us about students’ relationship to those goals. What do I mean by data?

Before I offer some specifics, I have to admit something: my former self — my early-career classroom teacher self — might have rolled my eyes at my current-coach-self writing an article on data-informed co-teaching. This is because I had a very narrow definition of data; I associated the word only with the scores that resulted from high-stakes and standardized testing. As a Special Education teacher, I was committed to seeing my students as more than a number, and so I resisted exclusively quantitative approaches to data analysis.

As a coach, I am still committed to seeing students as more than a test score, but my definition of data has broadened over the years. While quantitative data analysis might have its place, I have come to understand student writing, student surveys, exit tickets, student conferences, and classroom observation as valuable data points that should inform instruction. As you consider the examples below, I encourage you to think of these things as data, too. Using data to choose a co-teaching model

Here is a glimpse into how your classroom data might inform your co-teaching approach. Below are three of the six co-teaching models and how different data insights might lead you to choose that particular model.

You might use Station Teaching if…

You might use Alternative Teaching if….

You might use One Teach, One Observe if…

In reality, there are many factors that inform our decisions about our co-teaching approach: our physical space, our co-teaching relationship, our principal’s preference, or the amount of time we have to co-plan. Content-specific considerations are also crucial; not all lessons would be well-suited for a stations lesson, for example. I am not naive to these factors and the impact they have on teachers’ practices. At the same time, I think it is helpful to remember that our co-teaching approaches should be serving our students, and not the other way around.

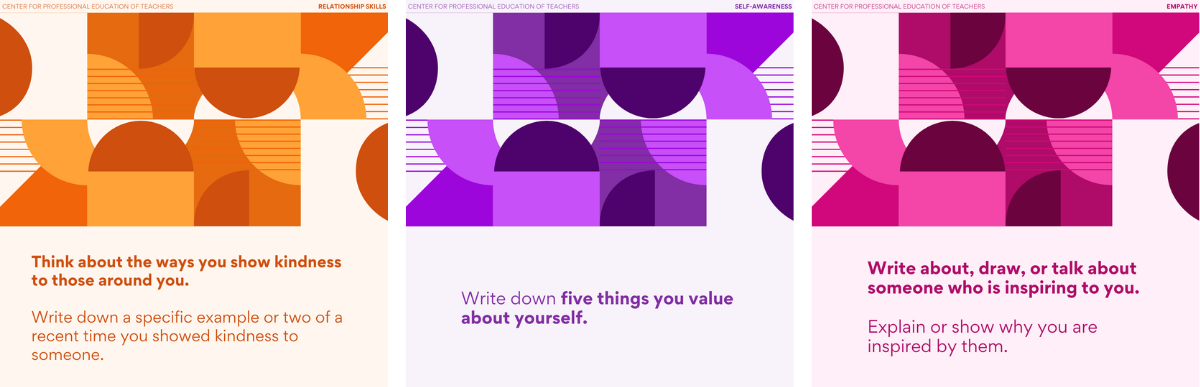

Create and sustain a space in which students feel good about themselves and others.

This is the second installment in our Rethinking the Three Rs series

In the previous article in our Rethinking the Three Rs series, we discussed how to create clear and consistent routines that communicate classroom expectations to students. Here we explore rituals, offering some approaches to developing and implementing them in your classroom in order to support a positive and productive climate of collaboration, and fun.

How do rituals differ from and enhance routines? Daily routines often get you moving in the morning — you may have an alarm clock set, lunch made the night before and ready to grab, or even clothes laid out the night before. You may start the day by checking for messages from work to confirm the day’s schedule. If I asked you about the rituals that make your days and weeks more positive and also productive, you may mention how you like your coffee in the morning, what you listen to on your way to work, weekly phone calls to relatives, text threads with friends, meals or drinks on Friday nights, shows you watch, special events, and holiday traditions. Rituals make life a little more special and give us something to look forward to. They create and maintain connections and relationships. In the classroom, rituals help to create and sustain community and support an inclusive culture where all students feel welcome, safe, and appreciated, supporting students’ mental health by helping them build relationships with each other and feel connected and acknowledged. Rituals can help us all look forward to learning together. Acknowledge and celebrate

Rituals may happen daily, such as greeting students as they enter class; weekly with a Friday game or special assignment; or intermittently as you introduce protocols for discussion or presentations.

Greeting students at the door is an old ritual, however, I believe that it can create important daily connections between teachers and each student. This greeting can include whatever style of ritual works best for you and your students — positive acknowledgements, personal connections, reminders, noting progress, a fist bump, handing out paper, or simply a smile and meeting a student’s eyes. Touching base with each student at the door also helps us to take the pulse of students’ moods and may offer them a chance to let you know something somewhat privately. Keep these interactions brief and make sure that you have a routine for students to immediately access once they enter the classroom. You can also say “goodbye” to students as they leave the room! Rituals can also include silly and fun or sincere personalized responses to special events such or celebrating student progress. These rituals may be instilled as you start the year and can also develop authentically as you get to know your students. Events such as birthdays and holidays can be acknowledged or celebrated in a variety of ways — and students can be offered choices of how they would like their birthday to be acknowledged. I have witnessed some wonderful rituals where a student may make choices such as to sit in a special seat, wear a special crown, eat a snack during class, or choose a special treat. Finishing a long unit of study or a long book, or making progress on key goals can also be reasons for rituals to sprout, with a special game or assignment that encourages connection. Perhaps students can be asked to acknowledge a classmate for helping them in some way or making the week or a lesson more positive. You may also encourage “shout outs” as a way to invite interactions, as frequently as makes sense for your students. They can be quiet conversations, posted on a board, or invitations to share out with the whole class. To monitor and acknowledge progress toward the end of year Regents Exam, one teacher I work with creates groups that compete to gain points as they collectively improve their scores on components of the exam. They can choose prizes and eventually, each group does “win” something. Acknowledgements in many forms can help create and sustain a space where students feel good about themselves and others. Build connections across the classroom

The most simple everyday classroom rituals can help create connections between individual students and weave a web of interconnected experiences across the classroom .

Stop and Jot is one such deceptively simple ritual for letting students get to know each other through sharing and processing their learning. To help students interact with more than just their neighbors or “elbow partners”, you may want to ask students to turn to talk to students on the other side of them, or behind or in front of them. You may also ask students to get up and move around the classroom to compare notes about a topic with a classmate who doesn’t sit near them. This can be done by asking students to find other students who “share a birthday month” or “have a pet.” These playful ways of encouraging students to interact with a variety of classmates can help create a connected classroom where students have interacted with a range of classmates. Concentric Circles is a discussion protocol in which students stand in two lines, facing each other to discuss ideas and then rotate down the line to eventually meet with many classmates. (Students have often told me that this is one of their favorite ways of interacting in the classroom.) Four Corners is a simple strategy where students are presented with a controversial statement or question. In each of the four corners of the classroom, an opinion or response is posted, and students move to the corner with the posted response that most matches their own. This structure encourages students to speak to a variety of classmates in a self-selecting process based on their opinions. Finally, Rotating Chair is a simple way to offer students the opportunity to look across the room and call on a classmate. With this technique, students raise their hands to speak, and then the person speaking will call on the next speaker, etc. (aiming to call on a person who has not/has less frequently contributed). Whenever the next student is called on, they must first briefly restate/summarize what has been said before them, and then, develop the idea further. Encourage group work and discussion

There are so many ways to approach group work; however, it always works best when students have roles and clear expectations for their collaboration and what they need to produce or demonstrate individually.

In her article, Getting Into Groups: Differentiation Through Strategic and Flexible Grouping, Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang offers an approach to groupings that prioritizes the strategic partnering of students. According to Dr. Kang, “Strategic grouping is a key feature in teaching effective collaboration skills, and in streamlining instruction to meet the needs of our diverse learners. Strategic — or purposeful — groups demonstrate that we’ve put some time, energy, and thought into who students should work with.” While groupings can and should be changed based on student data, it is also helpful for students to stay in a group for up to 6-8 weeks so that they can get to know each other, develop working relationships, and have a “homebase” in the classroom. In an era when many educators feel that students are less comfortable speaking up or engaging in discussion, creating “comfort zones” is important. Protocols, roles and responsibilities for group work When students are assigned specialized roles in group activities, it supports the classroom community by helping them feel acknowledged, which is necessary to the functioning of the group and a part of a mini-community. These roles also encourage full participation and responsibility. In groups, students’ roles and responsibilities may depend on the task — humanities teachers may be familiar with variations of literature circles, but STEM teachers can also identify roles whether they are for lab work or reading and discussing a text, or even reviewing multiple choice responses. Here are some simple protocols for a variety of group work that you may want to explore and adapt for your purposes:

Try creating your own classroom rituals! They may arise naturally in your classroom — maybe students will take the lead in suggesting or identifying productive and positive rituals for your class.

After we have established routines and expectations for managing and structuring our classroom, rituals are the moments and experiences that create a warm climate for relationships and positivity to flourish and grow in our classrooms.

Turn the obstacles created by shifting learning styles into opportunities for adaptation and innovation.

When it comes to education, every era has its defining tools and methods, each playing a central role. From the iconic chalkboards that once graced classroom walls to the overhead projectors that illuminated our lessons, these tools were fundamental in shaping our educational approaches. However, as technology continues to progress, these traditional tools are gradually being replaced by more advanced alternatives.

As such, education must evolve to keep pace with these changes, and teachers need to adapt to new technologies and teaching methods to effectively meet the needs of their modern learners. In a world defined by 21st century innovation, we can no longer rely on 20th century teaching methods. Yet, embracing change is no easy feat! In a whirlwind of shifts, resistance often arises, especially from educators who’ve experienced firsthand the loss and excitement of these transitions. Many educators find themselves grappling with the need to let go of cherished beliefs and teaching methods rooted in their own experiences and identities. In my recent conversations with teachers, a common sentiment emerges: the perceived disinterest of students in reading, their struggle with mastering basic skills like multiplication tables, and their apparent lack of engagement in critical thinking. These concerns are undoubtedly valid. However, as educators, we must confront the reality that today's students interact with reading, interests, and motivations in ways vastly different from previous generations. Accepting these changes can be difficult, especially when they seem to highlight deficiencies. But if we examine the changes and evolutions of trusted teaching methods of the past, we can gain insight into how technology continues to shape our ways of living and learning, setting the stage for understanding which teaching methods have become obsolete in today's digital age. The textbook

Modern textbooks became a staple starting in the 15th century. These trusty learning companions were used by teachers and students for generations and were praised for their wealth of knowledge evident in their heavy weight. Carrying a textbook was once a symbol of academic dedication, but in today's digital world, textbooks alone do not suffice. They're too basic for modern learners who want interactive, multimedia experiences, and as technology advances and access to information increases, textbooks just can't keep up with the engaging and personalized learning experiences students need.

The encyclopedia

In the 16th century, the encyclopedia was introduced. It was once praised as the most powerful source of human knowledge, jammed between two hardbound covers. I remember being fascinated by Encyclopædia Britannica and waiting in line to use the limited supply in our classroom. I would turn the delicate pages to find answers to all sorts of questions. But today, hard copy encyclopedias are obsolete. Students now have access to the vastness of the internet for instant information and real-time updates.

Library catalog systems

In the 19th century, we experienced the creation of the modern library catalog system, with its neatly indexed cards and Dewey Decimal classifications. It was once the key to the world of knowledge within a library's walls — it guided students through the maze of shelves, leading them to the books and resources they wanted to read. I distinctly recall my visits to the library, armed with my own shiny library card, seeking advice and assistance from the librarian, and paying fees when I missed the return deadline.

Yet, with the advent of digital databases and online search engines, the catalog system is a symbol of the past, replaced by instant access to a wealth of information at our fingertips. Furthermore, the act of reading itself has undergone a significant transformation. While some still cherish the smell and feel of a physical book, like me, checking out physical books has become a distant memory for many. Many people have embraced the convenience of accessing articles, podcasts, audiobooks, and other digital formats. The act of "reading" has expanded to include a wide array of mediums, reflecting the changing preferences and lifestyles of readers and learners in the digital age. The only constant is change

These transformations reflect the resilience of education in the face of technological advancements, underscoring that with change comes the potential for growth, adaptation, and progress. Librarians have evolved into “digital resource coordinators,” “media specialists,” and “information specialists,” guiding learners through the digital landscape. And traditional book companies have transitioned to online platforms for greater accessibility and customization.

Today, we're facing rapid technological changes, like YouTube, TikTok, and social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. There's also a growing presence of Generative AI, which, like changes in the past, can feel daunting. These advancements are reshaping the learning landscape, with some fearful of the implications for originality and personal privacy, while others view them as an opportunity to revolutionize education by offering personalized learning experiences for every student. The importance of reflection for innovation

I've been encouraging teachers to ask: What are the goals I have for my students? Where do these goals originate, and do they align with the demands of the 21st century? These inquiries prompt us to determine when adjustments are necessary, whether it involves letting go of outdated methods, revising our approaches, or affirming current practices.

Recently, I've observed educators designing innovative and relevant projects that deeply engage their students. These projects often culminate in products inspired by social media or TikTok videos, and sometimes incorporate QR codes for added interaction. For example, in a history class, students were creating short TikTok-inspired videos depicting key historical events or figures, using creative props and costumes to make the content engaging and memorable. These challenges can encourage active learning and collaboration among students, as they work together to brainstorm ideas and produce their videos. In a science class, I witnessed students engaging in a "Science Experiment Challenge" where they were tasked with filming themselves, with help from the technology teachers, conducting simple experiments and explaining the scientific principles behind them. This not only reinforces learning but also allows students to showcase their understanding in a fun and interactive way. In an art class, a teacher had her students showcase their creative projects by creating a series of Instagram- inspired posts including captions and comments, allowing them to document their artistic process from conception to completion. And in an ELA class, a teacher shared how she has been using AI platforms, like Brainly, to provide additional support to her students by offering personalized tutoring sessions, answering questions, and providing explanations on various topics, supplementing traditional classroom instruction. These examples demonstrate teachers’ efforts to stay updated on technological changes and connect with students by leveraging their interests.

Regardless of your sentiments around these shifts and changes, their impact on students cannot be denied. Therefore, it's crucial to shift our focus towards supporting students in developing the skills and competencies necessary for success in the modern world. Rather than viewing students' changing learning styles and interests as obstacles, we must see them as opportunities for growth, adaptation, and innovation.

By meeting students where they are and embracing their unique perspectives, we can foster a learning environment that encourages curiosity, critical thinking, and engagement with the world around them. This approach not only prepares students for the challenges of today, but also equips them with the resilience and adaptability needed to thrive in an ever-changing future.

References

The Journal of American History Textbooks Today and Tomorrow: A Conversation about History, Pedagogy, and Economics Encyclopedia Britannica

Rethink this co-teaching model that, when used thoughtfully, increases teachers' ability to respond to student needs.

Of the six established co-teaching models, One Teach, One Observe is the one that gets a bad rap. In my experience as a coach, working with leadership and teacher teams to make the most of co-teaching, One Teach, One Observe is often the one administrators want to take off the table completely.

“If I’m dedicating the resources of two teachers to one classroom, I want there to actually be two teachers in the room,” is something I often hear, in one way or another. And it’s understandable that there would be an expectation of seeing two teachers actively supporting and interacting with students in a co-taught classroom. At the same time, I would argue that when used strategically and thoughtfully, the One Teach, One Observe model is a powerful tool for formative assessment and data-informed teaching. Unfortunately, there are some common misconceptions that cloud our understanding of the model and prevent us from using it as such. Here are some common myths around One Teach, One Observe worth busting. One Teach, One Observe means we’re primarily observing the other teacher to see what they do.

Often, I see or hear the model suggested for newly established co-teaching teams — as a way for the newer teacher to get to know the style and practices of the more seasoned teacher, or as a way to learn from their expertise. While one could make a case for this in certain contexts, it’s clear that this diverts effort and attention from the students in the room — the opposite of our goals in a co-taught classroom. Instead, students should be the focus of our observations; the observing teacher collects data around how students are responding to information or engaging in classroom work.

The power of observation in the classroom is often acknowledged and discussed, but focused and sustained observation can feel like a pie-in-the-sky expectation when teachers face so many demands for their attention: a student comes in late and needs catching up, attendance is due, a video needs to be cued for the next portion of the lesson, two students need help settling a disagreement. The list goes on. This is the beauty of having two teachers in the room: one teacher can attend to these needs, while the other remains zeroed in on collecting the important data. The One Teach, One Observe model doesn’t require any planning or coordination amongst co-teachers.

While it is true that the One Teach, One Observe model may require less planning than other models — and can be an option when co-planning is just not possible — communication and preparation are required for using this model to its fullest potential. First, co-teachers must decide — ideally together — that a particular lesson or lesson section provides an important opportunity to learn more about students’ current understandings or performance with particular concepts or skills; it is important to remember that our goals for student learning inform our choices around co-teaching approaches, and not the other way around.

Second, we must decide the specific skills, understandings, or academic habits on which to focus our observations. In Teach like a Champion 2.0, Doug Lemov discusses the difference between simply “watching” students as they work, and “tracking” their progress through observation, with the latter meaning “the active seeking of the most important indicators of learning” (p. 45). In preparing to collect observational data during a lesson, we must ask ourselves: what specifically in students’ work or discussion will show me that they are “getting it”? We then must determine and prepare an easy-to-maintain system for tracking those specific “look-fors” (e.g. a list of student names, with a place to make a hash mark every time they refer to the map in their discussion on geographic factors). Perhaps the most coordination and preparation, however, comes with deciding what to do with the observational data once it’s collected — that is, how it will be used to make instructional decisions. Co-teachers might decide ahead of time that the data will be used to inform student grouping in real time; students who need further support with specific skills might work with one teacher in a small group, while the rest of the class continues on with the next learning objective. This requires having materials or teaching points prepared for the small group. Or, if the skills being assessed are not necessarily prerequisite to the day’s lesson, co-teachers might decide to look at the data together at the end of the day to determine differentiation or determine strategic grouping for the next day; perhaps students who would benefit from more practice with a particular skill will have a differentiated task, or the option to spend time at a learning center that supports them with review. In order to support co-teaching teams in all phases of planning, I have created an observational planning template to guide teachers in the before, during, and after of collecting observational data. One Teach, One Observe means one teacher is observing for the entire lesson.

This is a myth that applies to all the co-teaching approaches — that co-teachers should stick to one model for an entire lesson — when in reality, hybridizing or sequencing multiple models within a lesson is often the way to more effectively leverage them for student success.

This remains true in relation to the One Teach, One Observe model — if we are intentional and targeted in the type of data we are collecting, it is unlikely that observation is necessary for an entire lesson, anyway. Consider using this model at strategic points throughout a lesson — while students complete a Do Now activity, or for the first problem or question they are answering independently. This will free the second teacher up to provide more interactive support for the remaining time. The Special Education teacher should always be the one observing.

One of the drawbacks of the One, Teach, One Observe model — especially when used inflexibly or too often — is that one teacher might be relegated to an “assistant” role in the eyes of the student, a consequence we know can negatively impact classroom culture and dynamics. One way to mitigate that risk is to alternate the teacher observing and the teacher leading. This way, students see both teachers as instructional leaders, and both teachers have the opportunity to gain valuable insight through observation.

With two teachers in the classroom collaborating and working together toward student learning, the opportunities to respond to students’ needs increase dramatically. Observation is a relatively simple tool that becomes powerful when utilized thoughtfully by teacher teams.

Fundamental practices for navigating guidance and connection even in highly challenging environments.

CPET has had an ongoing partnership with East River Academy (ERA), the high school on Rikers Island, for many years, and I am one of several coaches who has worked on the Island, providing professional development support to a group of nearly 45 educators.

When you work at a school on Rikers Island, you have to plan your day more deliberately than you do at a typical school or workplace. This means packing your belongings in a clear bag, and double checking you have what you need, because there is no easy way to leave once you go through the four rounds of security checks. At the end of my first day working at ERA as a literacy coach, I finally got to the exit door and tried to open it, but it was locked. I looked back at a correction officer who chuckled at my naivete, “You can’t just walk out of a jail. Sign out here and show your ID.” We both laughed. One of my many rookie mistakes. Before you even get to the school, there is paperwork to confirm you have been vetted and approved to enter the Island. You have to tell all the people who might try to reach you during the day that you won’t be able to communicate until you get back to your car or locker at the end of the day, where you have to leave your phone. No computers are allowed inside the jail; only paper and pens. Actually, I started to bring pencils, because pens are coveted items in the classrooms, and didn’t want to get caught in the position of having a student inmate asking to borrow my pen instead of the golf pencils that students are given. I learned this the hard way, during one of my visits when a student asked to borrow my pen that I was using to take notes, and when I hesitated answering him, he became insulted and said, “What do you think I’m going to do with it? I just want to take notes with a pen!” I felt ashamed because I knew I could not give it to him, but also believed him that he wanted it for classwork. I shoved my pen back into my bag and apologized, preventing a potential issue for the teacher or even the correction officer in the room. From that point on — only pencils for me. Reaching for connection

I wish I could enter the schools inside Rikers Island with tools in my clear backpack to reach every single student and help every teacher.

The one who doesn’t speak but comes to class and keeps his head down; the one who only speaks Spanish but can’t read in Spanish, so it’s hard to even help him with translations; the students whose math or reading levels are so low that it is difficult to know what they can read or do beyond simple addition and subtraction; the students who are so insightful when we read a text, but put their head down when we ask them to write their thoughts; the students who are so struck by a visitor they want to talk to you, say hi, and let you sit with them and help them with the work. These students are perhaps the most heartbreaking, because I know I may not see them again when I leave the classroom, and while I don’t know why they are in Rikers at all, I just want to help them as much as I can in the tiny bit of time I have with them, and hope their futures turn around. One of the last students I interacted with asked me if I knew how hard it would be to become a plumber, and if it paid well. I told him he would need training and a certificate, but plumbing is steady, good work, and suggested he talk to his carpentry teacher about this goal. He asked me about it several times throughout the class. I reminded him that although he should talk to his carpentry teacher, all of his classes will help prepare him for plumbing: there is extensive math, science, technical reading, and creative thinking involved in plumbing. Keep going, I told the student, it is not going to be easy, but do the best you can, and let your teachers work with you. Framing my role

One day I was in an earth science class with a particular teacher who always referred to me as “Dr. Rigolosi.” I do have a doctorate, and this is my title, but in schools I tend to not use “Dr.” title because I have found it creates a distance that I’m trying to avoid. On this particular day, a student I was working with perked up and asked, ”Oh wait, you’re a doctor? What kind?” I dread this kind of question from a student because I know what comes next.

“I have a doctorate degree.” “So, are you like a pediatrician?” “No, no, not at all. No medicine, my doctorate is in education.” I could see the excitement on his face fade fast. He preferred the idea that I was a pediatrician. “So you are not a pediatrician or a doctor, but a doctor of teachers?” Saying it this way sounds so over the top. “Well, yes, that’s one way of putting it,” I replied. “So if you are a doctor of teaching, what are you going to teach me?” “I was trying to read with you about the water cycle. Let’s go back to your reading. I’m trying to teach you right now.” He agreed, we returned to the water cycle, but his enthusiasm was evaporating. These are the conversations that keep me on my toes. And humble. The young people who are incarcerated at Rikers are in limbo. Many of them are awaiting a court date. A depressing reality is that Rikers is mainly made up of boys or men of color from low-income neighborhoods of New York City. Some of them arrive at Rikers and begin to attend school more consistently than they ever had. So what on earth can I, or any of the coaches who enter the schools at Rikers, do to help support the teachers who are charged with looking after them? Bearing witness

Remarkably, the retention of teachers at Rikers is extremely high. There are many teachers who have worked there for two decades, and some of those teachers even teach summer school, too. We bear witness for teachers during both positive and difficult classroom moments.

Sometimes you have to be a bit creative to notice the positive moments in classrooms at Rikers. For instance, on a different day in that same earth science class, the teacher was presenting on rocks: igneous, metamorphic, sedentary. We looked at pictures in textbooks and projected on the screen, and noticed the differences between them based on how they were formed. “You know, Mr., this would be so much easier if you could bring examples for us to look at. It’s hard to tell the differences between them on the screen.” The teacher looked at the student with a straight face and said, “Son, I can’t bring rocks into a prison.” “Oh, that’s true, Mr. — good point.” Everyone started laughing and it was a moment of levity. Of course, they joked, the teacher can’t bring rocks into prison! It was a moment of students being curious and engaged enough to ask their teacher for resources, forgetting for just an instance about their reality. In a meeting with the teacher later that day, I reminded him of this class moment — it was a quick moment, and I was happy to have been there to relive it with him. This happens so often in my classroom visits — I am there to review with teachers the small but wonderful moments that happen in their classes. So many micro events happen throughout a day; reviewing some of the moments they may not have reflected on can be empowering for a teacher, helping them to feel seen. Listening or bearing witness to the more challenging moments is just as important. I’ve met with teachers who are overwhelmed by the circumstances — by the students who are there one day but not the next because of court dates or circumstances from their housing, because of the constant underlying tension between the students and the correction officer in the room, or the teacher’s awareness that the wrong look or words could escalate into a fight between students. Listening, witnessing, and staying present for teachers when we meet or when I am visiting their classrooms is a way to experience, even for a moment, the difficulties that the teachers and students endure daily at Rikers. Malcolm Knowles, a psychologist who specialized in adult learning theory, explains how the role of a teacher working with adults can be different from a teacher working with children. In adult learning, Knowles explains that an adult teacher is “more a guide than a wizard.” In Elena Aguiliar’s The Art of Coaching Teachers she takes this idea of adult teacher as guide and extends it even more: “a coach needs to be an expert at listening: It is this skill which we must excel at more than any other.” When working with teachers who are in particularly high-stress schools or working with high-needs students, making space to listen, ask questions, and helping them frame their teaching experiences is a way to coach them. Making space for the teacher to say what they are seeing in their classrooms, and what they are feeling about the often tumultuous environment is a way to bear witness as a coach. Providing tailored support

Every school has a school culture that we are either told about as soon as we enter the school, or we figure out shortly after. At some schools, for instance, we quickly realize the copy machine policy, or that the culture around birthday celebrations is a big deal (or not).

One of the constant challenges at East River Academy is that the student body changes somewhat quickly. Between court dates and issues with student-to-student fighting, the student population can change from day to day; however, some students are there throughout the semester. Knowing this about the particular student body at ERA, we try to tailor our resources so that units can be shortened or extended as needed. Short stories are more popular than novels for this reason, and essays based on a short text are a more realistic assessment than an essay based on a novel. Having introductory lessons for new arrivals is crucial, so helping teachers accumulate resources for this transient student body has to become a part of our professional support. This requires research and conversations with teachers to get an understanding of their needs, challenges, and strategies they have already tried. We also work on adapting curricula they are already using to make it work for their students. This is specialized professional development in and of itself, as we have helped restructure units and lessons to fit the school’s needs. We cannot go into this school (or any school) pushing a particular curricula or series of best practices. Instead, working with the teachers’ needs in front of us and providing resources for their unique population is key to truly supporting their work. Reflecting & moving forward

In one of our last professional learning sessions with ERA teachers, I was charged with providing resources on ways they can incorporate more small group work in classes. This is a particularly challenging topic for teachers whose students can have difficult — sometimes violent —relationships, and may prefer to work alone.

In retrospect, what I wish I pointed out at the time was that their students are actually doing small group work frequently, but in an organic way. Just that day, I had witnessed a pair of students pulling out characteristics in a story, and unprompted, these two students started pointing out examples in the text to each other and writing these examples down. When students were practicing for the GRE math questions, I noticed a pair of students start talking to each other about the problems. This paired group work was happening, but on their terms. My question should have been — what is the best way to handle these positive paired work moments? Should we highlight them in class, or will that ruin the moment, and make it feel too much like “school?” Should we nudge for paired work even if some students like to work in pairs and others don’t? Is it best to just leave the pairs working if they are working well, and perhaps after class, praise the students for working so diligently? Or does that kill the vibe? This is a very nuanced conversation, and one I wish I had with the teachers instead of reviewing the typical reasons and methods for implementing small group work.

The moments I am sharing here don’t really feel like mine to tell. I am not one of the teachers who works 180 days of the year on Rikers Island; there is a part of me that hesitates even sharing glimpses inside the prison. But I also believe these stories have value, and there is a portion of our population who spend a chunk of their youth in prison, and adults who have dedicated their professional lives to helping them.

We need to hear more of their stories, and I am offering a small window into their world. Many schools can be challenging and humbling; they can keep us all on our toes. Working at a particularly high-needs school requires high-level and sensitive coaching. Bearing witness by listening, observing, and holding a mirror for teachers to talk through their classroom experiences is a way to enter the coaching work. Tailoring the professional development and resources is fundamental; it has to work for the particular student body. Finally, being a reflective practitioner and acknowledging how I can improve my craft is challenging and can feel self-deprecating, but it is also an essential step to providing quality professional support. When a school is riddled with challenges, it can be difficult to know how to support teachers and how to help them grow as practitioners. These three methods offer a starting point, positioning the coach as an active listener and observer, and encouraging the coach to be honest about the effectiveness of their professional support, willing to modify and adapt the support to answer the school’s needs.

Embarking on a journey through project-based mindsets and influences, alongside educators in China.

Our mission seemed somewhat straightforward: a weeklong workshop series for teacher educators in Shanghai focusing on PBL, or project-based learning. Considering the many workshops we have facilitated over the past two decades, ranging from topics such as creating rubrics to analyzing data, running a weeklong workshop in Shanghai on the topic of project-based learning is as fun as it gets!

We have partnered with YouCH, a professional development group in the MinHang section of Shanghai for several years, and have already facilitated workshops for YouCH educators on topics such as teacher research, 21st century learning, and fostering teacher leaders. YouCH, which is a play on words for supporting “youth” throughout the “ouch” of adolescence, is based in China, and our CPET team — Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang, Courtney Brown, G. Faith Little, Dr. Lance Ozier, and me — were all returning to Shanghai and looking forward to working with our YouCH colleagues again. Our plan for the week was solid: participants would work on a meaningful, real-life, weeklong project that would end with a culminating celebration. Mornings would be devoted to working on different aspects of our projects so that teachers could experience project-based learning on their own; in the afternoons, we would zoom out to unpack these experiences by debriefing the scaffolds within our lesson designs and teaching strategies; and finally, participants would have independent planning time. Excited for our workshop and visit to Shanghai, we packed our bags and we were ready to go! Cut to real life, post-pandemic. China had recently relaxed all of its COVID restrictions, resulting in a surge of colds and respiratory illnesses. A day after we arrived, we learned that schools were closing for most of the week due to the fear of spreading illness, and it was too late to reschedule our workshops. The best laid plans… A cultural exchange for educators

Instead of facilitating workshops, we found ourselves engaging in discussions and smaller sessions with our YouCH colleagues, participating in more formal meetings with the principal for Minghin High School, on a visit to the Huang Gongwang High School in HangZhou, and in meetings with professors and education officials in the Shanghai district.

Everywhere we went, we were welcomed warmly with tea and coffee, fruit and treats, and with a genuine love and interest in incorporating PBL into more schools throughout China. At the Teacher Education Centre under the auspices of UNESCO, the director inquired about the possibility of facilitating our PBL workshops in the western, more rural region of China, as a part of the “Rural Revitalization” program for teacher professional learning. They shared with us the belief that social and emotional wellbeing are important aspects of teacher education, as well as creativity — both of which are also key ingredients for project-based learning. At the Institute of General Education Shanghai Academy of Educational Sciences, we were greeted with Starbucks lattes and highlights from the professors’ research and papers on the importance of PBL. The director explained that PBL should not just be a “snack, but the main meal.” They believe curricula should ask real world questions, and students should be able to express themselves creatively as they research and present the possible answers. Again, we were amazed by the enthusiasm for PBL as a method to be included in all schools. Witnessing PBL in Shanghai

We also had the opportunity to meet teachers at a YouCH conference on PBL, and these teachers were already doing project-based learning units. At this full-day conference, we listened as elementary students showcased their PBL artifacts. We were most struck by Steven, a high school student, who shared his project — “Let’s Break the ‘Wall’ Together” — on period shame, which shines a light on the notion that menstruation is normal, yet girls are made to feel ashamed or embarrassed when they menstruate. This project evolved into a fundraising and social awareness project to combat period shame through education, and to raise funds to provide access to sanitary pads in more rural areas of China.

Not only were these students doing PBL, but the topics were open-minded and refreshing! Talking more to the teachers and students throughout the day, we realized that these student presentations were from a class that was dedicated solely to project-based learning In other words, these projects were not woven into their core curricular classes, but completed through an additional class. This is not to diminish the impressiveness of the projects (we were fawning over them!), but to highlight that including project-based learning into the core curriculum is a different endeavor. John Dewey's influence

Over a brunch of steaming dumplings, fish stew, and noodles on one of our final days in Shanghai, we asked Principal Jian from the MinHang section of Shanghai why he was so inspired and committed to PBL. Where did this inspiration come from?

He responded in Chinese, but we heard a name we recognized well in his explanation: John Dewey. The principal reminded us that Dewey spent time in China — two years and two months, the longest amount of time he spent anywhere abroad. Our Chinese colleague proudly recalled how Dewey not only shared his educational philosophy when he was in China from 1919-1921, but how he learned from Chinese culture, and was influenced by Chinese philosophies and practices. What does this mean for our work? Knowing this now, that at the center of the PBL work is a proud connection to Dewey, how might this influence our workshops, if we are given the opportunity to return? John Dewey believed that we must “give the pupils something to do, not something to learn; and the doing is of such a nature as to demand thinking; learning naturally results.” (1916, Democracy and Education). We can’t argue against learning by doing, but what does Dewey’s concept really look like in schools, on a day-to-day basis? Lessons from Maxine Greene

One of our CPET colleagues, Dr. Lance Ozier, reminded us all that our late and brilliant professor at Teachers College, Maxine Greene, was a student of Dewey’s. We were the last generation of students to have had Maxine as a professor, and we briefly swapped stories about her. My closest interaction to her was when my Narrative Research class with Professor Janet Miller visited her at her apartment, since she was 88 years old and no longer traveling to Teachers College. I happened to have my baby, Javier, who was just a few months old at the time, with me at her apartment.

Our class of doctoral students had prepared so many questions for Maxine; we were starting our doctoral research and wrestled with issues over perspective, what it means to be a fair researcher, and hungry for any writing suggestions to avoid being total bores. Maxine listened to our questions and nodded, but really could not stop looking at my baby. “He’s so curious,” she kept saying, “He just can’t get enough of the world!” Here we all were, excitedly trying to absorb as much of Maxine as we could, and here was Maxine, mesmerized by a baby. She was in awe of my baby’s curiosity, a spirit akin to her own. This is the kind of curiosity at the heart of research, teaching, and learning. And at the heart of project-based learning. What I remember most about our afternoon with Maxine is not her answers to our questions (we had so many!), but her authentic curiosity and interest in what was happening in front of her, and on that particular day, that happened to be watching my baby interact with the world by touching and poking at everything in his range. When we return to Shanghai, it is this curiosity that we will have to bring back with us, this curiosity that is at the heart of PBL, and at the heart of Dewey and Maxine Greene’s work. How do we infuse this deep curiosity and learning into our curricula, and our daily lessons? This will be our charge on our return. The realities of PBL

Although we did not have our weeklong workshop series, we did spend one afternoon with 75 teachers from the MinHang School, and gave them a taste of our PBL plans. One of the takeaways from that group of teachers was the importance of teaching students to ask questions, and then using student-generated questions to drive a curriculum. But we also can’t ignore some of the concerns we heard from the teachers, specifically: “PBL sounds like a lot of work, and who is going to support us?” We appreciated the real and honest question, and agree this needs to be ironed out. A new way of curriculum planning requires professional learning and ongoing support from colleagues.

We arrived in Shanghai with a plan to invite teachers to experience and then deconstruct project-based learning. It was a solid plan, but if we return, we may also invite teachers to reflect on the roots of PBL in China, namely, how do you plan with John Dewey’s philosophy in mind? We will keep our workshop practical, but also return to Dewey’s research: What does the constructivist teaching model look like in real life? How can we allow for more discovery for students? The interest in PBL is palatable, as we discovered in formal meetings and informal conversations with our YouCH colleagues. Our colleagues at the Shanghai Academy of Educational Sciences said it best: how do we make project-based learning the meal and not the snack? This is our collective charge.

Empower students to assess their own learning and take charge of their educational experiences.

One of the most exciting things about project-based learning is that it lets students take control of their learning experience, allowing them to lead their educational journey. However, understanding what this truly means and visualizing what it might look like in practice can sometimes feel unclear and ambiguous.

For me, the above means fostering student discovery and embarking on a shared journey with students to achieve specific goals. One way I support teachers with this approach is through collaboratively establishing success criteria with students, rather than dictating them. Moss and Brookhart (2015) advocate for this process, emphasizing the importance of ensuring that students comprehend the learning goals and have a clear understanding of what exemplary work on a project looks like. This ongoing process involves teachers regularly monitoring and assessing students' understanding of learning goals and addressing any misconceptions that may arise.

Empowering student discovery

The significance of success criteria lies in empowering students to assess their own learning and take charge of their educational experiences, fostering a sense of self-efficacy. Students who believe in their ability to succeed are more likely to persist in their work, even in the face of challenges (Bandura, 1997). In essence, success criteria become a means to provide students with an opportunity to actively drive their own learning. Teachers play a significant role in this process by posing essential questions such as: What do I want my students to learn? How will I teach it? How will I know they got it? Similarly, students are encouraged to inquire about their own learning: What will I learn? How will I learn it? How will I know that I got it? When it comes to communicating success criteria, we can tell students explicitly, show them through modeling, offer examples, or support them in discovering the criteria themselves, whereby students are actively exploring, uncovering, and understanding concepts or knowledge on their own. Student discovery leads to deeper understanding, greater intrinsic motivation, longer retention of knowledge and skills, as well as promoting student ownership over their learning. To facilitate this discovery, I want to share four promising practices.

Promising Practice: Questioning

Engage students in questioning to ensure a deep understanding of project goals. Techniques such as putting learning targets in their own words, Think-Pair-Share, and an iteration of KWL (what we know, want to know, what we will need, what learning/skills we can lean on) can be effective. An example of series of teacher-facilitated questions as part of a project on the water cycle could sound like:

Promising Practice: Envisioning

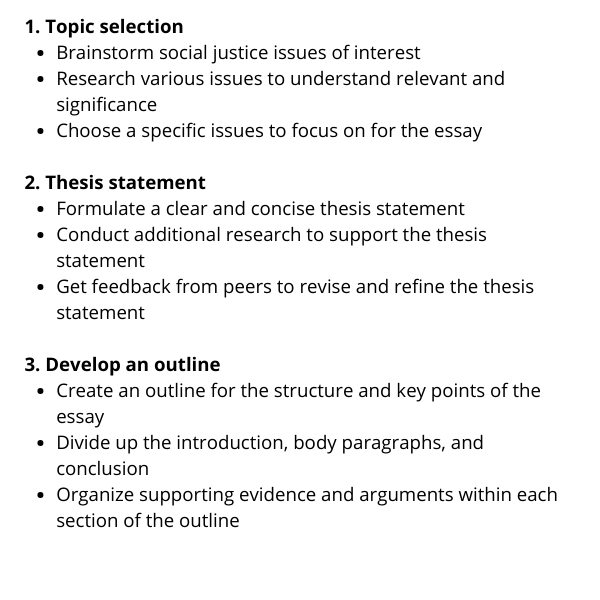

Support students in visualizing their goals and the final project outcome. Creating planning charts, breaking down tasks into smaller parts, and involving teachers in the planning process can enhance students' understanding and success. Here is an example of a student-created planning chart for a high school social justice project:

Promising Practice: Using exemplars

Expose students to examples of past work, encouraging them to analyze and describe its traits, features, and styles. This inductive approach allows students to discover project expectations through inquiry and exploration, promoting a deeper understanding. This could look like:

Promising Practice: Rubrics

Utilize rubrics not just for evaluation, but as a guiding tool throughout the project. Students can assess examples, rephrase or recreate rubrics in their own words, and use them to evaluate their own work and that of their peers, informing revisions. An example of this could look like:

The journey toward student-driven project-based learning is marked by the collaborative establishment of success criteria, enabling students to actively participate in their own learning. By implementing these promising practices, educators can create an environment where students not only understand the goals, but also take ownership of their educational path, ultimately promoting continuous growth and exploration.

Offer students the essence of project-based learning, within a condensed timeline.

“I’d love to do project-based learning, but there just isn’t enough time.”

I hear teachers say this all the time and it's understandable. Between the pressure to “cover all of the content,” days of instruction lost for testing, unexpected snow days and power outages, the uncertainty of student attendance, and uncertain access to computers and other technology — project-based learning (PBL) can feel like a logistically impossible feat. With that said, the concept of project-based learning appeals to many teachers, especially those who have used it with success in the past. The Buck Institute describes project-based learning as “[a] teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by working together for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an authentic, engaging, and complex question, problem or challenge.” When students respond to authentic challenges, we often see an increase in student agency and engagement. Students embrace the process to respond to a problem or challenge that affects them directly or indirectly, striving to acquire skills not out of a desire to pass a test, but rather to achieve a self-determined solution to a problem that will have a greater audience and impact outside of the classroom.

Condensing your timeline