|

Engage K-5 students in at-home activities that will help them enhance their social-emotional skills.

Enhancing social-emotional skills

Teachers know, perhaps better than anyone, what challenges students face when they learn outside of their typical classroom environment, or are only able to engage with their education virtually. They know the challenge of supporting anxious and overworked students who may have additional responsibilities to manage at home, limiting the time they have to devote to their own learning. Teachers also know that there are many students who, due to existing inequities, do not have access to the technology that is now a minimum requirement for learning in our new reality. Our Learning Through Living resources, which are designed to engage K-5 students in tech-free learning at home, can help you support your students, even when they don't always have access to your classroom. Through these resources, we hope to ignite curiosity and enhance students’ confidence in their abilities.

Using this resource

Included in this resource is a set of activities that allow young learners to use their everyday environment to enhance their social-emotional skills. Using minimal materials, you can use this collection to encourage play and creativity as your students explore reflection, tap into their imagination, and increase their self-awareness. You can also consider allowing older students to lead and teach those who are younger, or use the included ideas as a springboard for new ways to play and think about social-emotional learning.

To access additional free K-12 resources from our team, please visit our Resources page.

Engagement is a highway that leads students to their goals, and it is our job to build as many on-ramps as we can to capture all kinds of kids in all kinds of ways.

As educators, we often see the main priority of in-person schooling as the development of academic knowledge and skills, and that priority has carried over to the online learning space. Students, however, typically view school as a way to be a part of their social community. Seeing and being seen by friends is a huge factor for student attendance, and even in-class engagement. The social-emotional component of school is identity forming; it's where students develop a sense of self beyond their families, and the close quarters of the in-person classroom organically enhance this experience. But when we’re not together in the same place (or we’re together, but we’re socially distanced or wearing masks), authentic opportunities for students to connect with one another disappear.

In addition to finding a peer group, establishing relationships, and making connections with other students, school is the place where students can make a healthy connection with a caring adult who isn't a member of their family. Many students, especially those who are young, feel a close connection to their teachers. They give gifts, share hugs and high fives — in their little lives, teachers may be some of the only non-family adults they know, and some of the only adults they can develop a relationship with independent of a parent or a sibling. In the transition to remote learning, the opportunities for this type of social-emotional support and connection have almost fully evaporated, even as schools have figured out ways to provide academic opportunities.

Activating social-emotional engagement

The three pillars of student engagement — academic, intellectual, and social-emotional — are about maximizing any opportunity that can help bring kids to class. Academic engagement, or even just showing up, can lead to meaningful intellectual engagement, and that, in turn, can lead to organic social and emotional community experiences that meet students’ needs. Even students who are struggling to sign in to class or struggling to find meaning in instructional activities can still be motivated to connect on a personal level. What kind of social-emotional interactions do kids have? Think about the different types of organic connection points we find when school is in session, and then consider ways to match them with our online experiences.

Our hope is that students who haven't been "showing up" to school might show up to opportunities like these. If they do, it will refuel their energy and strengthen their social-emotional engagement with school, helping them to deepen personal connections that re-energize their sense of self. We can then leverage these connections to increase academic and intellectual engagement.

If we see student success in school as tied to anything — especially now — it is student engagement. Engagement is a highway towards students achieving their goals, and it is our job to build as many on-ramps as we can to capture all kinds of kids in all kinds of ways.

Meaningful classroom discussions are one of the greatest components of student engagement — and they can still happen remotely.

In addition to the excitement (and anxiety, let’s be real) of beginning a new year and a new teaching semester, we all now have the added worry about how we will adapt or continue with our hybrid classrooms or remote teaching, without meeting our students face-to-face. Like many of you, I am prepping to teach online this spring, and my courses will be a mix of asynchronous and synchronous instruction — terms I had never considered before teaching during a pandemic.

There are some perks to teaching online of course, particularly the lack of commute and the choice to dress professionally enough for a Zoom meeting. But preparing to teach online has spurred me to research the best practices for teaching remotely. I know what an engaged class looks like in person, but will I be able to match that same level of engagement in an online setting? To be clear, I believe an engaged classroom is one where the students are doing the deep thinking, discussing, writing, and reading throughout the class. For so many teachers, classroom discussions are not only one of the greatest joys in teaching, they are essential for student learning and engagement! And most teachers are evaluated through Charlotte Danielson's Framework for Teaching, which highlights teachers whose students are actively problem-solving and discussing complex concepts. So, how can we have meaningful class discussions remotely? Is it possible?

Asking questions

As I listened to Teaching Today’s episode on this topic, I kept pausing to jot down notes that will support my instruction. The episode’s panelists — Courtney Brown, Dr. Cristina Romeo Compton, Dr. Sherrish Holloman, Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang, Dr. Marcelle Mentor, and Brian Veprek — left me with takeaways that I can implement in my own online classrooms, to help promote discussions during a time of distance learning. Who’s doing the asking? When we create space for students and encourage them to ask questions about our curriculum, we are putting students in the driver’s seat, and allowing their curiosities to drive the curriculum. This is a way for students to buy into the learning, and as Cristina notes, encouraging students to ask questions about the curriculum or texts is a powerful way to promote engagement. The importance of having students generate their own questions (instead of replying to a teacher-created question) is punctuated by the concept developed by Roberta and Brian: when students are the ones who are driving the learning, there is no need to worry about student buy-in. Speaking of students asking questions… Grade school students often ask “why?” and are frequently less self-conscious about asking questions. Secondary or adult learners can be more guarded and do not always feel comfortable sharing their questions or wonderings. Teaching students which questions are the most fruitful for a discussion is a great technique for all ages. The Question Formulation Technique (QFT) is one option for teaching students how to practice asking a variety of questions about a particular topic. This protocol encourages students to pose both “closed” or “open” questions, and then students decipher the different types. No matter how teachers use this protocol, student questions often lead to more engagement and deeper content knowledge.

Small group discussions

Sharing in a low-stakes way In the timeless Mind in Society, Vygotsky (1978) advocated for student discussion explaining, “By giving our students practice in talking with others, we give them frames for thinking on their own.” In the spirit of giving students “frames for thinking on their own,” having them discuss academic ideas in small groups is a less intimidating way for students to share their thoughts. For synchronous classes, Zoom breakout rooms can replace small group discussions. Creating Zoom breakout rooms, perhaps after a jigsaw reading or as a way to practice sharing in a low-stakes way, is a way to replicate small group discussions. Teachers can join each breakout room to listen in and observe, just as they would circulate in a classroom. Of course, teachers can be concerned that students may get off task in breakout rooms, but this is the same issue we face in in-person classrooms — we can’t be everywhere at once. As Roberta points out, we aren’t really in control — we only have the illusion of control. Familiar breakout groups Don’t switch it up! If you’re teaching a group of students for the first time and the class meets synchronously via Zoom, Courtney suggests keeping breakout groups the same, at least for the first part of the year. While the instinct may be to switch groups so students can get to know each other, starting the year with online or blended learning is different from anything most of our students have experienced. If issues in groups arise, then it may make sense to revisit grouping, but if possible, try to keep the groups the same for an entire unit — maybe even for the semester. This will help students build a community within the group as their interaction with other classmates is so much more limited. And as with any group work, it is always important to discuss norms, expectations, and set routines for small (and big) group discussions. Include breaks Even though you’ll be able to see students' faces through little boxes on your computer screen during big group discussions in a synchronous class, you may have a harder time “reading the room” — anticipate having to insert writing breaks and purposeful pauses in order to give students time to process and participate. Documenting discussions One way to help students notice their thinking during a discussion (and to encourage them to stay on task) is to have them share or post their discussion notes. This is also an effective way for teachers to notice patterns and themes that are emerging in student thinking. How can we take notes during an online discussion? Google Docs If students are already using Google, asking them to utilize a Google Doc for notetaking (perhaps one ongoing document that they add to for each discussion) is a practical strategy. In Google Docs, students can take turns as the notetaker, and others can add to the document if anything is missing. As Brian points out, teachers can notice who is participating in taking notes on their discussion by checking the doc’s version history. This is a way to see if students are, in fact, all adding to the notes. In addition to joining breakout rooms, viewing groups’ Google docs in real-time is a way to gauge which group is on their way, who needs help, and how much time they may need to continue their discussion. Chatting within Zoom For full class discussions, asking students to write in Zoom’s chat feature is a simple way to capture students’ ideas in real-time. At the end of the Zoom call, Marcelle recommends that the teacher copies and posts the chat on their class website as a record of notes from that day (much like a chart paper of class notes on the classroom wall). I’ve been concerned about how I would capture class discussions the way I would in a physical classroom — now, we can all write our ideas into the chat, and voila, there is a record of our class! But remember — the Zoom call has to end before the chat can be copied.

Asynchronous discussions

Discussions don’t always have to include talking One of the perks of asynchronous learning is that it can allow for more flexibility, and help lessen any anxiety students feel about live video calls. Using platforms such as Padlet or Google Jamboards are alternatives to having shared, written discussions. Marcelle suggests a quote-centered protocol for moments like this — students are asked to share (in writing) quotes from the class text, and then their classmates are asked to respond to the quotes, taking time to consider why the quotes are significant. This is not only a helpful option for having a discussion asynchronously, but also a chance to give students a break from face-to-face interactions. Protocols can be your discussion friend Providing simple discussion frames with sentence starters like “I believe this means...”, “This is significant because…”, or “As a next step, perhaps…”, offers students a meaningful way to discuss a topic, or process a text or problem set. Students can begin by jotting down their ideas in writing, which will help prepare them to share their ideas in a discussion — asynchronous or otherwise. Not sure where to begin? Try our What, So What, Now What? tool that supports student observation, analysis, and inquiry. Low-tech options require your imagination Marcelle suggests using a phone app such as WhatsApp to send out discussion prompts to students, and asking them to write back within the app. Teachers can then collate the responses and report back to the class what others have written. Another low-tech option involves breaking up your class structure, pairing students up, asking them to exchange phone numbers, and having them call each other on the phone to have a conversation on a particular topic! Let them write up their conversation, and post or share it with you or the class. Similarly, you can pair students up to explain the written assignment, and ask them to write letters to their partner, then send via USPS! It will cost students about $.50, but what a delight to receive a letter in the mail! (Of course, there is no way of screening letters, so you may need to set up some parameters). It seems ironic to suggest these systems of communication for an online class, however students (and teachers!) may appreciate these alternative ways of discussing concepts.

After listening to the Teaching Today team and reflecting on their conversation, I am recommitted to believing that meaningful classroom discussions can still happen during distance learning. And while I am still concerned about teaching online (what if my students have weak wifi? What if my wifi is wonky? What if my own kids are having a difficult time working independently while I’m teaching?), I also realize these issues are somewhat out of my control. I now feel more confident incorporating discussions into my online classrooms — even while teaching in a blazer and yoga pants.

Our challenge is to redesign what engagement looks like, what it feels like, and what it takes to get kids onboard — because engagement is everything.

When we consider some features of a “good student”, we might think of someone who uses a quiet voice and raises their hand, or someone who comes to class organized, turns their work in on time, and always has a pen and paper. But one problem with the attributes on this short list is that none of them address learning! While some may enhance the learning process, most of these characteristics are actually about behavioral compliance. Which prompts me to ask: how much of in-person school is actually about compliance, rather than engaging in learning?

Compliance is the act of conforming, yielding, adhering to cultural norms, and cooperation or obedience. Compliance is focused on a mindset of having power over students, rather than empowering them. And whether we’ve recognized it or not, in-person learning is dominated by compliance-oriented structures which often mimic the behaviors of engagement. We structure how students enter, exit, and move throughout the building, we structure where they sit, how they sit, when they can go to the bathroom or eat food. Let me be clear — we need to structure many elements of student interaction in schools to create a safe and productive learning environment, but we often confuse the results of compliance with engagement. Or at least, we used to. COVID changed all of that. As school doors closed and students’ laptops and tablets dinged with notifications, educators quickly saw how compliance gave us a false-positive on engagement. Without the same physical constructs, the social construct that motivates compliance disappeared, and one by one so did our students. Muted, video off, not present in the chat, missing synchronous calls, submitting late or incomplete online assignments — as students disengage from school during remote learning, educators are overwhelmed, disoriented, and discontented. This isn’t what anyone has signed up for. But COVID hasn’t given us any problems we didn’t already have. So our challenge is to redesign what engagement looks like, what it feels like, and what it takes to get kids onboard — because engagement is everything.

Pillars of engagement

In our work across schools, we’ve come to see three pillars of student engagement: academic, intellectual, and social-emotional. While many attributes of these pillars are organically supported during in-person learning, they all must be explicitly pursued during times of remote or blended learning. In his book Drive, Daniel Pink explains that for adults in the workplace, intrinsic motivation is nurtured by three elements: autonomy, mastery, and purpose. And in fact, the same is true for students — with scaffolding, of course! Working within Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), learning is enhanced when kids can find Flow, which Csikszentmihalyi describes as a state in which people are so involved in what they’re doing that nothing else seems to matter. These three theories work together to illustrate the engagement that empowers students to take responsibility for themselves and their learning in all circumstances.

Pillar 1: Academic engagement

Academic engagement is the type of engagement that is required for students to complete their academic tasks. Tapping into executive functioning skills, academic engagement is all about helping kids to show up, stay with it, and stick the landing. Teachers know that kids can’t learn if they aren’t in school — the same is true if they aren’t logging on, can’t find their Zoom link, or lost their password, again. Many executive functioning skills like working memory, cognitive memory, and inhibitory control create major obstacles for students who want to do well, but have such a difficult time regulating their behavior that they aren’t able to hang in long enough to let the learning process work. Especially during these challenging times — and, let’s be honest, during non-pandemic times as well — our students will be better off when we create deliberate structures, procedures, rituals, and routines to support them. To develop specific strategies, first consider what types executive functioning skills are students struggling with. Is it planning? Working memory? Time management? Is it self-control or initiative? If we can pinpoint where or how students are struggling, we can design aligned strategies to help them cultivate these skills.

Pillar 2: Intellectual engagement

Once students are showing up and staying with their classes, it better be worth their while! If they perceive our content to be dull, or find our assignments to be too easy or too hard, they won’t stick around for long. Creating opportunities for intellectual engagement is essential to reeling in students’ interests, gifts, and talents. Intrinsic or internal motivation is a very difficult thing to cultivate in someone else — but through personal challenges, purposeful tasks, and propelling curiosity, we can trick our students into learning while they’re having fun surfing the internet, or playing games. First, we must think about ensuring that our assignments are differentiated and are creating a purposeful challenge for students at every level. When kids can hit that just right instructional challenge, they’ll keep working to reach their goal — just like they do in video games, sports, and other hobbies. We increase the likelihood that students will stay engaged when we can help them to make real-world connections, pick and choose elements of the assignments they complete, and when we propel their curiosity by creating opportunities for advancement, acknowledgement, and future challenges.

Pillar 3: Social-emotional engagement

Some say the term “social distancing” was a mistake, and that instead, it should have been “physically distant, socially connected”. The reality is that while educators view academics as a school’s main priority, socialization is a huge factor in what brings students to the school building everyday. Social-emotional connections seem to come naturally between students in peer groups as well as between students and teachers during in-person learning. But online, there are far fewer opportunities to bump into someone, stop by their classroom, or check in with them in the hallway. These are critical moments of social interaction. And for young children and adolescents, these moments aren’t just about making them feel happy or have fun — they actually help to shape identity. As educators, we must consider strategic ways to increase student-to-teacher relationship-building outside of the virtual walls of the classroom, giving students a place to connect, ask questions, and share openly. Additionally, we can create opportunities for students to engage with other students without tackling academic concepts. Especially when the school year is marked by massive interruptions, mask wearing that covers up facial features, and months of isolation, students need moments where they can just be with other kids.

Engagement can seem elusive, especially when all of our interactions are mediated by the digital world, literally boxing us in. But we can’t let these challenges get the best of us. Our current circumstances can help reveal what true student engagement looks like, when not limited by the components of in-person compliance. As you explore new possibilities, bring a colleague along for the ride. It’s not just the students who are isolated and struggling to get and stay engaged. Each of these pillars applies to us as adults as well as to our students.

Offer your students an opportunity to authentically engage with content, even when learning remotely.

Over the past year, school has been a rollercoaster event filled with openings, closings, virtual connections, and dramatic shifts in teaching and learning techniques and experiences. No matter the grade level or subject area, our learning spaces have been completely redefined. And it isn’t just due to in-person or online learning schedules — many teachers are finding that what worked in person may not be working as well online or in other virtual settings. Additionally, changes to state tests and other accountability measures have created opportunities for teachers to redesign their teaching methods and learning outcomes to authentically engage students in the core elements of their content areas.

Finding ways to engage students in content can be difficult, particularly when so much teaching and learning is happening remotely. We understand this challenge. Our Literacy Unbound team faced the same concerns about how to engage teachers and students in our 2020 Summer Institute — traditionally a 2-week, in-person immersive learning experience. Rooted in the belief that students learn best through authentic inquiry, curiosity, and through the multimodal embodiment of a text, Literacy Unbound brings teachers and students together with teaching artists to explore the in-depth themes of a shared text, independently. In a typical summer, we would develop a series of Invitations to Create as a way to invite and entice students into the world of the text. These invitations might prompt readers to journal, draw, collage, create a playlist, or explore some other form of expression related to a key quote or “hotspot” in the text. As readers collect their responses, they traditionally come together for a dynamic experience in which they construct an original performance based on their responses to the invitations. While much of the in-person institute needed a complete redesign to fit a virtual institute, the structure of Invitations to Create did not. Invitations provide the perfect setup for virtual reading, writing, and collaboration. And they come with plenty of choice, freedom, and personal exploration, which means that participants can be authentically engaged from the very beginning.

Creating your invitation

Even though Invitations to Create begin as prompts to pieces of literature, they’re extremely flexible and are a promising practice for all content areas and grade levels during remote and/or blended learning experiences. How can we begin to incorporate invitations into curriculum for math, science, and social studies, and beyond? To get a sneak peek of the process, we’ve developed the sample below to experiment with Invitations in Mathematics, adapted from A Guide to Crafting Invitations to Create by Dr. Nathan Allan Blom. Note: As you read, look for the examples in blue of building an invitation for A Mathematician’s Lament.

Step 1: Jot

Whatever the content, there are literacy expectations in your field. What are the reading and writing requirements in your field? In your course(s)? In the exam? Jot down some of your thinking as a warm-up. Step 2: Identify What is a text you go back to over and over again that you want to introduce to your students — or -- what is a text you already plan to use in a future lesson? Have the text handy.

A Mathematician’s Lament by Paul Lockhart

Step 3: Choose Choose a “hotspot” within the text. This is a passage of the text that captures your attention. Typically, it’s helpful if a hotspot contains:

Explain in a few words the context of the hotspot within the larger text.

In the first chapter, the author shares about a nightmare an artist has about how art is taught so that children don’t hold a paintbrush until they are young adults. Instead, they learn about art for years before they experience it for themselves. He says that life is very much like that in the real world of mathematics:

“Everyone knows that something is wrong. The politicians say, “We need higher standards.” The schools say, “We need more money and equipment.” Educators say one thing, and teachers say another. They are all wrong. The only people who understand what is going on are the ones most often blamed and least often heard: the students. They say, 'Math class is stupid and boring,' and they are right.” Step 4: Offer Offer an idea you had or a connection you made during your reading. Share with the voice of a fellow student, rather than an authority on the subject.

This makes me wonder how much more often math is seen as boring instead of beautiful.

Step 5: Connect Connect the hotspot to a piece of media to illustrate and/or extend your connections, questions, or ideas. Explore media to find something that connects and inspires you, like:

Video: The Beauty of Mathematics

Step 6: Prompt Create your prompt, using this structure: In whatever way seems best to you (equation, movement, experiment, poetry, prose, music, art, video, etc.), explore ______. Let's look at our invitation for A Mathematician’s Lament created from steps 1 - 6:

A Mathematician’s Lament by Paul Lockhart

In the first chapter, the author shares about a nightmare an artist has about how art is taught so that children don’t hold a paintbrush until they are young adults. Instead, they learn about art for years before they experience it for themselves. He says that life is very much like that in the real world of mathematics: “Everyone knows that something is wrong. The politicians say, “We need higher standards.” The schools say, “We need more money and equipment.” Educators say one thing, and teachers say another. They are all wrong. The only people who understand what is going on are the ones most often blamed and least often heard: the students. They say, 'Math class is stupid and boring,' and they are right.” This makes me wonder how much more often math is seen as boring instead of beautiful. Listen and watch this: The Beauty of Mathematics In whatever way seems best to you (equation, collage, drawing, music, etc.), explore the idea that, in the real world, math is beautiful. Include directions about how students will share their creation with you and each other. This process supports students to make their own meaning of the text, and is also a way for you and your students to experience an invitation together, whether you’re in the same concrete or virtual space. If possible, create your own response to the invitation and share it at the same time your students share theirs.

Each invitation offers an opportunity to reflect, analyze, and synthesize the text at hand. Once the invitations have been developed, students are invested in their interpretations and eager to share their ideas. This sharing is a powerful tool, inspiring motivation and encouragement across the community.

What can you invite students to create using this simple and effective structure?

Promising & practical strategies to help track the growth of children's literacy skills.

When you’re caring for children who are participating in remote learning, it can be challenging to identify and understand their progress and growth as readers. You’re likely wondering: Am I doing this right? Are we making progress? How will I know? When children are in the classroom and engaged in in-person learning, the responsibility for these questions largely lies with their teachers. However, the new normal for teaching and learning requires equal — if not more — participation from parents, in order to support and ensure the advancement of students’ reading skills.

Given how busy we are trying to balance our own work responsibilities along with the needs of our children, it can often feel easiest to default to tools like reading comprehension quizzes, multiple choice tests, or even worksheets to help recognize and assess reading progress at home. While these measures can be helpful, they certainly don’t tell the whole story. We could be missing out on identifying areas of growth and celebration, as well as a robust understanding of our children’s areas of struggle. But there are promising — and practical — strategies that parents can utilize to help monitor and track the growth of their children's literacy skills. Don't feel as though you need to create your own assessments, rubrics, or projects to achieve this — that is, unless you have the time, capacity, and energy! Instead, consider some quick, informal strategies to monitor students’ growth. These strategies can tell you a lot about a child’s reading behaviors, habits, and progress.

Habits & behaviors of good readers

In her book, 7 Habits of Highly Effective Readers, Joanne Kaminski explains, “Kids who are highly effective readers and score high on their state exams seem to have similar habits.” She goes on to explain that she has seen these habits in her own children as well as children she’s taught and tutored. The seven habits she describes are:

This list can be helpful to parents as they look for evidence of their children's reading behaviors. When these behaviors are present, you can feel good that your young learners are on the right track! As we level up our understanding of a child's reading progress, we can turn to Mosaic of Thought: The Power of Comprehension Strategies, in which the authors Ellin Oliver Keene and Susan Zimmermann outline a list of habits that are more reflective of the kind of work students are doing while reading, including:

For parents, a list like this can feel daunting. You may not know how to look for these specific skills, and are likely asking yourself questions, such as: How do I know they are inferring? How can I prompt them to determine what’s important? Identifying skills that children are exhibiting during reading is often left to teachers. Knowing what to look for There are ways to simplify the identification of reading habits and skills so that you can determine what children are doing before, during, and after their reading. We can break down more complex reading habits into observable actions, behaviors, or concrete examples that signify the deeper learning that is taking place. When it comes to reading, we can look for the following: Stamina If your child is reading for long(er) periods of time, this is great! Interest and stamina are very important, especially as books increase in demands and complexity. Fluency Have your child read to you! This can be a great way to monitor fluency, decoding, and self-correction strategies on the part of students. Comprehension and thinking skills: A simple set of questions can be very telling when it comes to a child’s predicting, inferring, and comprehension skills. You can use these same questions each time they read, and students can either answer for you, or as part of writing and drawing exercise. Here are some suggestions for what you can ask a child before, during, and after they read:

Thoughts about reading Talk to your child about what they are reading. Ask them about the kinds of books they are reading, what they're enjoying (or not enjoying), and why. This can help you gain insight into your child’s general attitude toward reading, the kinds of books they gravitate toward, and the types of books that they find easiest to read.

When you've got young learners in your home, you deserve a lot of credit for balancing work, at-home learning, childcare, and household tasks. What you’ve been able to do during this unique time has been nothing short of remarkable. Remember that when it comes to supporting learning at home, we can monitor a child's reading progress with simple strategies that make the process feel useful and manageable for everyone involved. Start with a strategy that feels feasible and accessible, and build from there. Happy reading!

Three strategies for taking the pulse of your class, when teaching online.

Although I have been teaching via Zoom for several months, I don’t know if I will ever truly adjust to speaking to my computer and seeing the faces of my muted students in little boxes. But Zoom etiquette, as we have all come to learn, is to mute when someone else is speaking so everyone can hear the speaker. Herein lies my main discomfort as a Zoom teacher: to speak to my students and to not hear their little sighs, mmhmms, and quiet huhs?, has been my biggest unexpected challenge. It’s hard to get a sense of what my students are thinking or reacting to without hearing these small sounds. And while I know I can’t rely on these impulsive responses as a form of assessment, they’ve always helped me take a quick pulse of my class to check for understanding.

I’m not suggesting that we use the impromptu reactions of our students as a way to assess them — but as teachers, hearing students’ reactions nudges us to wonder, Is this a good place to stop? Do I need to check in with a few students? I miss that. So with our students on mute (unless they are speaking), formative assessments are as essential as ever in online teaching. James Popham, the assessment guru, explains that “formative assessments help students learn” because they are “assessments for learning;” not “assessments of learning.” In other words, formative assessments gauge how much our students are understanding or processing information; the purpose is not an assessment for teachers to grade for accuracy, but for teachers to use to adjust their lesson planning. After all, formative assessments are often linked to effective teaching practice. The Black and Wiliam Research Review, from over 20 years ago, “shows conclusively that formative assessment does improve learning.” (Black and Wiliam, 1998a, p. 61).

Recipes for success

I have used a variety of formative assessments in online teaching, and they each serve a different purpose. Here are the formative assessments I am currently using while teaching online: Consistent breakout groups As Courtney Brown mentions in Discussions During Distance Learning, it is best to keep students in the same small groups throughout the semester, instead of randomly grouping them. When students are online, they have no chance to get to know each other — there is no partner share, no turn and talks, no walking into class together and making conversation. To implement this with my students, I put them in small groups using the breakout rooms feature on Zoom, and then used the polling feature to ask students whether or not they were okay staying in these same groups throughout the semester. This would allow them an opportunity to form deeper connections within their group, and feel more comfortable interacting with one another. Thankfully, they all answered “yes.” Once students are in the same groups, they are able to visit our class Google Drive folder where they can find folders for each week we meet. For each class, I create a simple note taking template that changes depending on our topic of the day, and students use these templates to capture their small group discussion ideas. When students return to the main group, they share these documents with all of us by sharing their screen in Zoom. While students are in their groups, I can assess how they are doing in two ways — first, by popping into each breakout room, to hear moments of their conversations and to see if they have questions; and second, by viewing their Google documents to see how they are progressing. This is my favorite way to check in on my students’ learning in real time — viewing their writing as it happens helps me determine who may need some more scaffolding or assistance, as well as which group is already finished with the note-taking document and may be ready to move on. It is also my way of noting which students are writing in these documents, thanks to Google’s editing feature. Flipgrid To vary how students discuss their learning, I turn to Flipgrid as a way to hear students’ takeaways from class. First, I create my own video to model what they might say in theirs, using a text or discussion topic we have already discussed previously. This way I don’t steal any of their good ideas! By demonstrating how I would like them to respond to a text (by discussing quotes, or connecting the text to a real-world connection), I help them craft their Flipgrid video. To ensure my students watch others’ videos, I ask them to reply to at least two other classmates’ videos on our class discussion board. Using Flipgrid as a formative assessment is a way to assess student learning, using an alternative genre. Padlet I often use Padlet as a type of “exit slip,” or as a way for students to give me feedback. When asking students for the latter, I make sure to update our Padlet’s settings so that participants can submit their responses anonymously. Both types of Padlets will include a direct prompt, such as: What did you learn today about ____? What questions do you still have? Students can see each others’ responses, and they, too, can get a pulse on how our class is doing and what their classmates are thinking. When I ask for feedback, I might prompt them by asking, How is our class going? Or What suggestions do you have? This is a great way for me to receive feedback directly, and because it is anonymous (a must for this kind of teacher feedback!), I trust that students can be more honest. Using a Padlet board as a formative assessment is a way for me to check for their understanding, confusion, and gather overall suggestions for our class.

Teaching online has pushed me to become even more intentional about how I informally assess my students, and how I use those assessments to adapt my instruction. I will continue to find more ways to include formative assessment in my classroom, not only because these types of assessments lead to more effective instruction, but because I know it makes me more responsive to my students’ needs — especially when I can’t rely on hearing their in-the-moment responses during class. When we return to normalcy, I can’t wait to hear their thinking sounds again.

We must face the realities of our current teaching and learning situation — and then find ways to adapt.

The sunlight is still Summer while the breeze feels like Fall. Teachers stream in, eager to find their names at check-in and chat with colleagues on their way to hear the keynote speaker frame the day, “It’s not that differentiation is part of the work. Differentiation is the work itself. We all can make progress and we can all grow. Each student deserves a goal that they can work hard to achieve!"

This excerpt from a previous post about bringing a series of in-person professional development workshops to life evoked memories that seemed to stand in stark contrast against our current teaching and learning situation.

Adapting our plans

We began our Spring 2020 workshops series on a cold day in February. At the end of the day-long sessions, facilitators reviewed feedback from participants, noted adjustments they would make to their plans, and tucked away sign-in sheets in folders, ready for their next session — a month away. A few weeks later we found ourselves siloed, setting up spaces at home where we could work, on screens, day and night. It felt as if we were living in a snow globe that someone picked up, shook, and set back down, leaving our environment sloshing around us, debris floating through the air, settling at our feet. We moved quickly, collaborating from our siloed spaces, pushing one another to reframe our thinking:

Through connection and communication, we were able to find ways to support teachers who were going through the same process themselves: expanding their classroom from inside the walls of a school building out in the city, across the state, and around the world. The phrase we're in this together became a mantra not only when it came to wearing masks, washing our hands, and social distancing, but also when it came to our own teaching and learning. Stay-at-home restrictions created an environment in which we needed to open our minds to as many options to meet as many students in need as possible. As teachers — from early childhood education to graduate school — revised and remodeled their plans, many began to ask, “Why didn’t I think of this before? I could have a distance learning component for each of my lessons.” At CPET, we realized that we could not only offer each of our workshops in an online space, but we could make all of our offerings available at no additional charge to our participants. The limitation of being in a specific session at a specific time was gone, and what was left was the opportunity for teachers to experience as many of the asynchronous offerings as they cared to.

Our Spring 2020 asynchronous offerings; view upcoming opportunities here

Utilizing practical strategies

Of course, after plans are adapted into a new space, the work again becomes customizing to our students. What do our first graders need to connect during distance learning? What about our sixth graders? Our seniors? As our snow globe settles and our vision clears, we see that trusted strategies are a foundation we can still hold on to. We can identify practical and adaptable tips we’ve used in the classroom and integrate them into our remote teaching and learning.

So, we end where we began: differentiation is not simply part of the work — it is the work.

Each student deserves the opportunity to grow, demonstrate progress, and work hard toward an achievable goal. Each teacher deserves the same.

Creating multiple pathways for students to approach their learning will allow them to increase their personal and academic engagement.

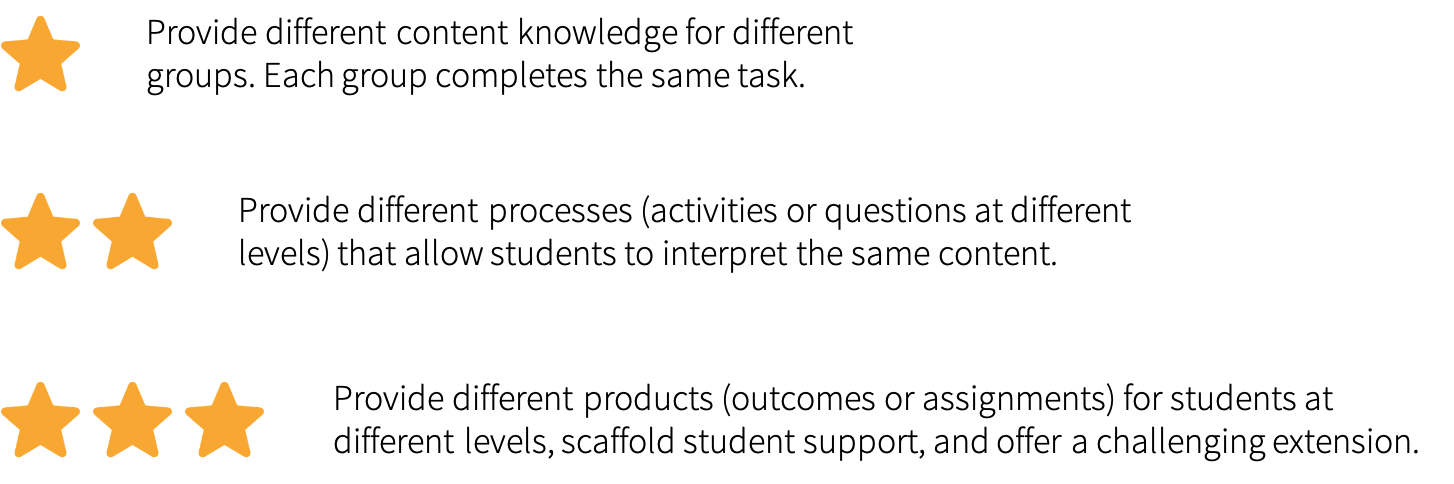

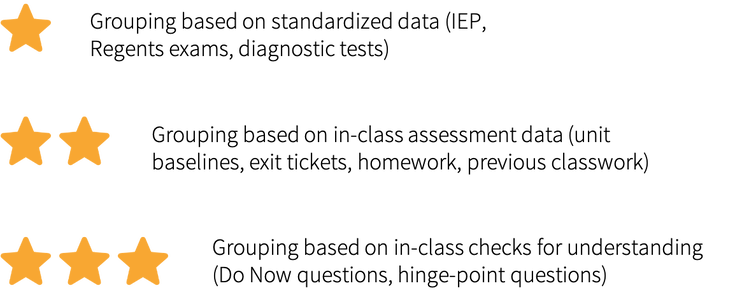

Differentiation can happen in many ways, with varying levels of complexity. Our Differentiating Like a STAR resource, designed to help educators consider entry points to differentiation, offers strategies in four categories: data, task, text, and grouping. Within each category, we outline three levels of instruction — the more stars included, the stronger the differentiation. By identifying pathways to expand differentiation, you can add depth and complexity to your lessons.

When teaching in person, we differentiate tasks by dividing content material, offering multiple processes to fit students’ learning styles, or varying the product to ensure interest and engagement. Differentiating at a distance may change our communication methods, but it doesn’t need to change our commitment to student choice. In fact, it can enhance it!

Pathways for differentiation

One classic way to differentiate instruction is to create different paths for students to demonstrate their learning. There are three ways that educators can differentiate based on the assigned task: content, process, or product. Content As you develop your curriculum, you may identify a series of content strands that students should be familiar with, and that are representative of a larger concept or theme within your instruction. When we differentiate content, we can identify some concepts and examples that are necessary for all students to know deeply, and other concepts that students should be familiar with, but may not be required to know in-depth. Differentiating this content allows educators to present a wide range of examples or scenarios as a means to teaching towards a larger concept. When differentiating content, every group takes the same steps to complete the same final product — but they begin with different content information. For example:

Product Sometimes, it is in students’ best interests to focus on the exact same content, particularly when content strands are essential to students’ understanding of a discipline, or are represented on mandated assessments. In these cases, we can keep the content the same, but invite students to represent their learning in different ways. By giving students choice in how they demonstrate their learning, we help them to tap into their natural creativity, curiosity, and intrinsic motivation. When differentiating products, it’s important to develop a scoring guide that focuses on the key content concepts that need to be represented, and to align each product outcome with those expectations. For example, you might present your students with three project options: a three-page essay, a PowerPoint presentation consisting of 10 slides, or a three-minute video. Each project can be evaluated based on the same content information and should demonstrate the same application, analysis, synthesis, evaluation, or collaboration skills. Process When preparing students for rigorous, high-stakes assessments, you may not have the freedom to pick and choose the content or the final product. In these cases, you can look at opportunities for differentiating students’ processes. Consider differentiating through process by providing various supports for students. Perhaps some students receive a glossary of key terms & definitions, while others receive a word bank, and others receive no vocabulary assistance at all (because they don’t need this additional support to make sense of the content). You can also use student notes to support process differentiation — consider inviting some students to make use of outlines, while offering two-column note taking, webs, and bullet points to others. Whether they’re working individually or in small groups, giving students a choice of how to engage in their learning process can feel highly personalized, which will enable them to walk with their best foot forward.

Making the most of online learning

When working in the world of remote teaching or blended learning, our typical teaching strategies may seem difficult to translate, which leads to defaulting to whole-class instruction that does not leverage student choice or differentiate based on student needs. But the online space offers just as many — if not more — opportunities to differentiate the task. High-Tech Many educators working in communities with on-demand access to technology are able to differentiate a task through content, process, or product using their online platform. Whether you’re using Google Classroom, Canvas, Blackboard, Moodle, or your own website, you can offer options at key points along the learning journey. In fact, it’s even easier to provide task options through distance learning, since there are no printing requirements! Within each lesson, we can create opportunities that maximize student choice. In high-tech spaces, we can post multiple assignments, graphic organizers, or focus topics and invite students to choose which they’d prefer to work with. Students can even work across class periods and be grouped with students who have shared interests, levels, or thinking processes. Students can also meet virtually through video conferencing, create small group videos, or share their process notes through pictures, video reflections, and digital artifacts. Low-Tech Some students have access to technology, but experience limitations due to time on their device, internet access, or support with using advanced features of applications. In these situations, the differentiation of content, process, or product should be made clear to students in their assignment. They may benefit from having their assignment personalized for them, and they may need flexibility if they are able to mix online and offline work. This can mean posting the task so it can be downloaded for later use (rather than just existing on a website), and creating materials that students can complete using their computer, but that don’t require internet access. No-Tech Students in the “no-tech” access category likely have less than one hour per day to access the internet, and may be logging on from a phone or tablet that isn’t connected to a printer or scanner for managing hard copy printouts. Teachers can offer entry points for these students by creating custom materials using picture models or short videos that explain what and how to complete a task with the materials they have on hand. Keep in mind that no-tech assignments can ask students to write out their responses by hand and submit assignments using photos. These assignments might also include packets of strategies or resources that can be picked up at school (and for convenience, can be picked up/dropped off during the same hours as food distribution), phone calls or text messages to students, or the option to send/receive materials by mail.

Differentiating tasks is one way we can increase student interest. Students are drawn to tasks that are personally relevant and challenging — creating multiple pathways for students to approach their learning (process), demonstrate their learning (product), or customize their learning (content), will allow them to deepen their understanding and increase their personal and academic engagement.

Distance learning can be challenging, especially for our young, emerging readers. What can we do to support them?

Distance learning can be challenging, especially for our young, emerging readers. In the classroom, young students are exposed to print-rich environments, and are supported and guided through a multitude of literacy activities such as phonics, guided reading, shared reading, and direct reading instruction. Now that learning is taking place in the home, there are growing concerns about the deficits young students will experience, particularly when it comes to reading. What can we do? How and when should we do it? And how can parents prioritize reading practices at home?

As a Master’s student, the focus of my thesis included understanding and improving the reading habits and attitudes of my third grade students. I launched my study by administering a survey, and provided them with a number of statements including, I like to read, I prefer reading to watching TV, and I read more than I watch TV. I had students read each statement, and then circle an emoji that best matched their feelings about the statement (ranging from positive to negative). My students’ responses, along with my observations, were pretty discouraging. I noticed many of my students didn’t want to read, or would read for a few minutes before putting their book down and saying, “I’m done.” I was determined to do something. In the next phase of my work, I reached out to parents of those students with particularly negative responses to the survey, and asked if they would be willing to participate in my study. Their participation included signing a contract in which they agreed to engage in three specific literacy practices at home: reading aloud, shared reading, and independent reading. It is these three literacy practices that I think parents should prioritize, as I believe they are simple, effective, and particularly helpful when it comes to supporting reading development outside of the classroom.

Reading aloud

Reading aloud promotes fluency and exposure. Exposure plays a significant role in reading development and cultivating a positive attitude towards reading. The parents who participated in my study agreed to read to their children for 20 minutes a day, at least three times a week. I would encourage all parents to do the same. If you can do nothing else, read aloud to your child! Expose your children to as many books as possible, and regularly engage in read alouds. This can be incorporated into a lunch break, added to a bedtime routine, or even occur first thing in the morning — whatever works best for you. If this feels too difficult, there are many read aloud resources available online that can support you, such as Epic, which offers a massive digital library for children aged 12 and under, and YouTube, which offers free access to a variety of voices and titles to choose from. If you’re ready, interested, and able to step up your read aloud game, you can engage your children further by asking simple questions: What do you notice? What does this make you think? What are you learning about ____? This kind of work promotes comprehension and inferencing skills. The tried and true think-aloud protocol — in which you share what you’re thinking and what you’re predicting — can also be a powerful model for children. I even do this with my 8-month-old. As her mother I know she’s brilliant (of course!), but can accept she is clearly too young to do deep thinking work on her own, so I point to the pictures and the words in each book, narrating what they are, for as long as she lets me. It’s never too young to cultivate a love for books!

Shared reading

Fountas and Pinnell define shared reading as a reading experience in which children and their teacher engage in multiple read alouds of an “enlarged version of a text that provides opportunities for students to expand their reading competencies. The goals of the first reading are to ensure that students enjoy the text and think about the meaning. After the first reading, students take part in multiple, subsequent readings to notice more about the text.” From there, students discuss the text, and parents or educators determine next steps for support. Ideally, parents would be able to put on their teacher hat while reading with their children, tracking and pointing to the words together, sounding words out along the way. Shared reading like this can help improve the rate at which children read, increase their fluency, and add to their enjoyment for reading. Don’t be discouraged if this feels outside of your reach. Shared reading can also mean simply engaging in shared reading time, without any additional components. Each family member can select a text of their choosing, and read near each other. Whether this happens first thing in the morning, as you read the newspaper or your favorite magazine and enjoy a cup of coffee, or before bed, as you are winding down the day and in search of some quiet time. Being exposed to others who are reading can have a positive effect on a child’s attitudes and habits around reading, as it did for my young readers.

Independent reading

The final activity in my study involved an agreement from parents to provide quiet and uninterrupted time and space to engage in independent reading for at least 20 minutes a day. One of the biggest challenges to reading at home, according to my third graders, is the lack of space and opportunity to read alone. Children are often sharing rooms, household tasks and chores need to be done, and child care responsibilities need to be managed. This, I’m sure, has only been exacerbated during the COVID-19 crisis, as everyone is now living and working from home. Home can feel even more chaotic than before, and quiet time can be a challenge. However, if you can find a calm space where children can engage in independent reading even for even small periods of time each day, it can have a positive impact on reading abilities. This space might be the corner of a room, on a bed, or even in the bathroom. We have to get creative! If you’re ready to level up your independent reading game, task your child with practicing one simple strategy while they read. This might include asking them to jot down questions as they read, notice and note (What do you notice? What does this make you think?), or it could involve a challenge to find words that start with certain letters or that contain certain blends, such as Bl or Cr. It doesn’t have to be complicated, just one strategy that will allow children to practice on their own, and then share with you.

The last tip I’ll leave you with is: if it feels like these strategies aren’t working for your readers, be prepared to throw all these strategies to the wind. Put the book down, and try again later. This is a challenging time — stress and emotions are running high — and we all know that the dynamic between parents and children, when it comes to learning, can be difficult and unpredictable. Some days our children want our help, and sometimes they don’t want anything to do with us! Give yourself some grace and flexibility. Trust that what you’re doing is enough, and remember that one day will not create lasting, negative implications for your child’s reading abilities. Be kind to yourself and to your children, and remember that tomorrow is another day.

Developing social-emotional skills can help students better care for and advocate for themselves and others.

Balancing teaching your curriculum with finding time to discuss with students what they are experiencing and how they are feeling can be challenging. Yet staying connected with them and what they are going through is essential in order to continue supporting them. Students are dealing with many significant life changes and a range of emotions, many of which can be traced back to the shifts they've experienced during the pandemic — worrying about their own health and that of their family members and friends, feelings of loss about missed experiences, navigating a new form of learning, and being confined to their homes with their family members.

Supporting self-reflection

Bringing low-tech self-reflection practices into your classroom can be a helpful way to address the social-emotional needs of your students. Developing social-emotional skills can help students of all ages better care for and advocate for themselves and others. One way of incorporating at least a few minutes of self-reflection into lessons is by using social-emotional prompts (download a full set of our SEL prompts here). Our prompts are organized into several categories, drawn from the core social-emotional competencies identified by the educational research organization the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. Prompts fall into the following categories:

Using these prompts with your students

These prompts can be sent out over email, posted on a class’s online feed, or shared aloud during a real-time class. Students can respond to them in a variety of ways — using tech-free (drawing or writing in a journal), low-tech (typing in a document, making a video recording, making an audio recording, taking photos), or high-tech options (posting responses to a shared classroom file, such as on Google Drive). Before using these in your classroom, give yourself time to engage in your own self-reflection practices (through these prompts or other means) — this will support you in more thoughtfully facilitating social-emotional learning exercises for others. Take the time to introduce the idea of the prompts to your students. You may contextualize the prompts by sharing that they’ll help with self-reflection during this strange period of confusion and uncertainty. For students to fully express their answers, they may not be comfortable sharing any or all of their responses — determine what you think would be best for your students. There is still significant value in students responding to each prompt, even if they choose not to share with others. Below are a few ways that you can use these with your students in your online classes: LOW-TECH

HIGH-TECH

If we can begin to see some of our professional obstacles as opportunities, we can forge new pathways that will carry us forward, even when the current crisis is behind us.

Nothing is going according to plan.

Across the world, the swift transition from in-person to online education as a result of COVID-19 has created anxiety, uncertainty, grief, and a host of complex challenges for educators. Whether the transition caught us by surprise or we saw it coming, we have all faced unexpected obstacles in the wake of this crisis. But if we can begin to see some of our professional obstacles as opportunities, we can begin to forge new pathways that will carry us forward, even when the current crisis is behind us.

Designing curriculum

Obstacles Designing curriculum is hard enough, but designing a remote learning curriculum in the middle of a global pandemic is completely overwhelming. Curriculum design is often customized to the features of a time-bound, classroom-based experience, to which at-home learning bears little resemblance. Can we translate the qualities of in-person learning to diverse groups of students who will have different entry points to learning and varying levels of access? Can we provide rigorous instruction to students when exams are canceled? Can we continue with the curricular units we had planned at the beginning of the school year, even if they aren’t aligned with at-home learning? Opportunities Within each of these curriculum challenges is an opportunity that can be unlocked with one word — how. Rather than “can we...", let’s try “how can we...in high-tech, low-tech, and no-tech ways?” By asking how, we can focus not on obstacles, but action steps. This shift in our thinking can act as a catalyst to reexamining our goals, methods, and design for learning. In this moment, we have the opportunity to reimagine our curriculum for maximum engagement, intellectual curiosity, and cultural relevance. In-person learning is constrained by quantities of time: attendance, punctuality, and class periods, to name a few. Because at-home learning doesn’t exist within the same parameters, it presents an opportunity for educators to design curriculum that will engage students in learning at their own pace.

Demonstrating learning

Obstacles At the same time, at-home learning lacks the immediate presence of a classroom teacher who can answer questions at a moment’s notice, or a classmate to consult. As a result, at-home curriculum must be more explicit than its in-person counterpart. In person, a teacher may typically make oral announcements, or take loose notes on the board. To engage students in an intellectually rigorous at-home learning experience, teachers will likely need to be more detailed, more explicit, and provide more models, examples, and visuals in order for students to deepen their understanding. Opportunities As teachers articulate the nuances of content for an at-home learning experience, we have a new opportunity to develop robust materials and resources that will serve students’ needs, even when in-person learning resumes. For teachers, this type of deep reflection and planning is a unique professional learning experience that deepens our own understanding of our content and methodology. For at-home learning, teachers may want to consider structuring weeklong assignments in the form of mini-projects or inquiry investigations that will allow students to vary the time spent on them each day. Some may want to break up their learning into daily chunks, while others will be able to dive deeply into the experience for a longer period of time. The ultimate goal is not the precise number of minutes students spend on the activity, but rather how they are able to demonstrate their knowledge and skills related to the objectives. It doesn’t matter if they complete the task in 5-minute or 45-minute increments, or across 3-4 hours in one sitting — what matters is what they learn.

Connecting to students

Obstacles In-person teaching is dependent upon a teacher’s presentation skills, and their rapport with students. At-home learning requires a completely different approach, as teachers are not physically with their students. This can be very disorienting for teachers who find their energy and satisfaction from being around kids and seeing their students’ eyes light up during an a-ha! moment. Being separated from their students can leave teachers feeling isolated, disconnected, and wondering if anything they’re doing is working. Opportunities Distance learning requires us to consider all of the ways in which we can deliver content without being in the same room at the same time. Our first task is to acknowledge that our go-to model of instruction may not be possible at this time. But while distance learning is different, it doesn’t need to diminish the teaching or the learning experience. We want to start by asking questions: How do we design an opening activity to draw students into their learning? How do we deliver our mini-lesson on a new topic or concept? How do we provide students with meaningful tasks and provide feedback in a timely manner? One option includes synchronous video calls, where students log on at a specific time and engage with their class virtually. The benefits here are that teachers can present their lesson, engage students in peer-to-peer discussions, and answer questions in real time. However, this approach assumes all students have access to technology, and are able to engage at the same time without interruption. This isn’t always the case — and when students can’t engage online, it creates major concerns around equity and access. It’s for this reason that many educators see asynchronous learning as a promising practice. Using simple technology to create instructional videos, screencast presentations, or even audio recordings, teachers can present their lesson one time and distribute it 100+ times to their students in low- and no-tech ways. One of the benefits of recorded lessons (even when we aren’t teaching through a pandemic) is that students can re-watch the lesson as many times as needed in order to understand the information. This is a critical support for students who have learning disabilities, or are learning English as a second language. Being able to pause, go back, and re-watch the lesson can bolster students’ confidence, increase their comprehension, and clarify their questions. After the lesson is designed and delivered, teachers can shift their focus from delivering instruction to providing personal support, feedback, and task modifications for students at all levels. This might look like holding office hours, offering weekly check-ins with students, email correspondence, or phone calls with students or caregivers who don’t have access to technology. Using these strategies, distance learning can be expertly differentiated, highly personalized, and deeply relational.

In a time that feels topsy turvy, we have to be honest: nothing is going according to plan. This fact is scary, disappointing, and de-centering, and can produce a considerable amount of anxiety. Whether we’re novice teachers or veterans, school leaders or policymakers, we are educating in a time that requires us to find new opportunities for offering meaningful, relevant, and academically engaging learning experiences to our students. Being open to these opportunities will serve us well, even when we’ve safely returned to our classrooms.

Three strategies you can offer students of all levels — even when you can only connect virtually.

What happens when your class is full of 30+ students who have different strengths, different learning styles, and different comfort levels with the English language? We’ve been tackling this question alongside K-12 educators through PD series like Educating ELLs and Including All Learners, where we address the promises and challenges of teaching in heterogeneous classrooms by exploring the principles of differentiation and related research for classroom applications.

When we began another round of Including All Learners sessions last year, we set out to support a new group of educators as they worked toward their differentiation goals. We didn't yet know that we would soon experience social distancing, that toilet paper would become the most coveted household item, or that both teaching and learning would rapidly transition from in-person to online. During this time of online schooling, we are particularly concerned about students who either do not have online access, or do not have a quiet nook in their homes to learn. A few years ago, one of our students commented that he slept with the English novels from our class under his pillow — it was the safest place in his home, where he didn’t have a workspace of his own. As we write this from our individual homes and reflect on the recent shift to virtual education, we are focusing on the principles of our Including All Learners series that remain true in any kind of teaching and learning environment. Below, we will outline a few concepts from our workshops and share how they carry over to our online learning experiences. Disrupt the single story We begin our sessions with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED Talk, The Danger of a Single Story. She explains to her audience how all of us, including Adichie herself, have told a singular version of someone’s life story, and have also been victim to a single story about ourselves. She shares how damaging and incorrect these single versions can be. This concept serves as a reminder that we must disrupt the single stories that are often assigned to our students, particularly those who are ENLs or are students with disabilities. This can be more challenging than it sounds, particularly when students have to be described in IEPs, which do not allow for a more complex telling of their life stories. In our workshops, we challenge ourselves and participating teachers to share other versions of our students’ stories — something you can continue to do in online communication with other adults in your community.

What helps some students can help all

One of the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is that what helps some learners can help all learners. This concept can be illustrated by the design of public spaces — for example, people of all ages and abilities benefit from public bathrooms that are wheelchair accessible; they are wider, are often designed without entry doors, and are therefore easier to navigate and offer fewer opportunities for spreading germs. One way we try to illustrate this concept in our workshops is by providing all participants with tools that support their learning. For example, while we view the Adichie TED Talk, we offer our participants a simple graphic organizer (like a double entry journal) that allows everyone to listen fully, while also allowing them to recall specific compelling moments in the talk. Our double entry journal includes two components: a column on the left, partially filled out with quotes from the text (in this case, the TED Talk), and a column on the right, which is open for viewers to share their thoughts. Returning to the ideas presented in UDL, a double entry journal that includes specific lines from the text is useful for students who have central executive challenges, but in reality, everyone can benefit from the text references. The principles of UDL feel particularly important at a time when it is more difficult to ask students where and how they need support. Just as we provided a partially completed double entry journal for all of our participants, consider making your scaffolds accessible to all students on your online platforms. This might look like providing possible sentence starters to all students for written explanations, or providing a series of clues for students solving a math problem.

Show the messiness of thinking

Metacognition expert Dr. Saundra McGuire defines metacognition as simply thinking about your thinking. Being able to think about how you’re making meaning of a piece of writing — as well what you can easily understand and what you can’t — is an important aspect of engaging with complex texts. One tool we offer educators is a model of a think aloud, where we simply model the messiness of the thinking that goes into making sense of our reading, writing, and problem-solving. The goal is to dispel the idea that a text suddenly and magically makes sense without struggle and hard work, and to show them that everyone relies on thinking moves that help them chip away at difficult texts. Consider doing this type of think aloud with your students online — either in real time or as a short recorded video. Rather than simply creating a video where you explain the major steps needed for answering a question or solving a problem, try to capture yourself actually doing the work, making even your smallest thinking moves visible — the questioning, rereading, reasoning, and revising that often happens while engaging in higher-order tasks, but that we often do without even realizing. You might also share things like how you knew to begin your answer in a certain way, or what bit of information caused you to stop and double-check your computations. Sharing these micro thinking steps will help students see that there is not a singular way to answer a question or to solve a problem, which may help them become more aware of their own thinking.

As you continue adapting your instruction for remote and blended learning, we hope you will utilize the tools and concepts we have outlined here to ensure you are reaching all learners. While our in-person sessions are on hold, you can continue to participate in professional development on this topic by joining us online.

Without the limitations of an in-person classroom session, new opportunities for engagement have space to emerge — even for students without on-demand access to technology.

According to the glossary of education reform, student engagement “refers to the degree of attention, curiosity, interest, optimism, and passion that students show when they are learning or being taught, which extends to the level of motivation they have to learn and progress in their education.” Evidence of learning and indicators of engagement can be commonly observed and relatively easily measured in traditional classroom settings — teachers can monitor students’ behavior as they raise their hands, participate in whole group discussions, or support their fellow classmates in small, cooperative learning groups.

During this time of remote learning, educators around the world are facing a student engagement challenge, as classrooms have transitioned to virtual learning spaces. Instead of in-person teaching and facilitation, computers, tablets, and phones have become the primary tools students use to engage. These changes have also highlighted issues around equity, as every home learning environment doesn’t offer students the same level of access to technology. And yet, teaching and learning can and will continue — educators around the world have already been reimagining the ways in which they can engage their students. Without the limitations of a 45-minute classroom session, the challenge of hearing 25-30 voices during a short period of time, and the barriers of in-person, adolescent dynamics that make some students less inclined to speak up in front of their peers, new opportunities for engagement have space to emerge.

Peer-to-peer engagement