|

Fundamental practices for navigating guidance and connection even in highly challenging environments.

CPET has had an ongoing partnership with East River Academy (ERA), the high school on Rikers Island, for many years, and I am one of several coaches who has worked on the Island, providing professional development support to a group of nearly 45 educators.

When you work at a school on Rikers Island, you have to plan your day more deliberately than you do at a typical school or workplace. This means packing your belongings in a clear bag, and double checking you have what you need, because there is no easy way to leave once you go through the four rounds of security checks. At the end of my first day working at ERA as a literacy coach, I finally got to the exit door and tried to open it, but it was locked. I looked back at a correction officer who chuckled at my naivete, “You can’t just walk out of a jail. Sign out here and show your ID.” We both laughed. One of my many rookie mistakes. Before you even get to the school, there is paperwork to confirm you have been vetted and approved to enter the Island. You have to tell all the people who might try to reach you during the day that you won’t be able to communicate until you get back to your car or locker at the end of the day, where you have to leave your phone. No computers are allowed inside the jail; only paper and pens. Actually, I started to bring pencils, because pens are coveted items in the classrooms, and didn’t want to get caught in the position of having a student inmate asking to borrow my pen instead of the golf pencils that students are given. I learned this the hard way, during one of my visits when a student asked to borrow my pen that I was using to take notes, and when I hesitated answering him, he became insulted and said, “What do you think I’m going to do with it? I just want to take notes with a pen!” I felt ashamed because I knew I could not give it to him, but also believed him that he wanted it for classwork. I shoved my pen back into my bag and apologized, preventing a potential issue for the teacher or even the correction officer in the room. From that point on — only pencils for me. Reaching for connection

I wish I could enter the schools inside Rikers Island with tools in my clear backpack to reach every single student and help every teacher.

The one who doesn’t speak but comes to class and keeps his head down; the one who only speaks Spanish but can’t read in Spanish, so it’s hard to even help him with translations; the students whose math or reading levels are so low that it is difficult to know what they can read or do beyond simple addition and subtraction; the students who are so insightful when we read a text, but put their head down when we ask them to write their thoughts; the students who are so struck by a visitor they want to talk to you, say hi, and let you sit with them and help them with the work. These students are perhaps the most heartbreaking, because I know I may not see them again when I leave the classroom, and while I don’t know why they are in Rikers at all, I just want to help them as much as I can in the tiny bit of time I have with them, and hope their futures turn around. One of the last students I interacted with asked me if I knew how hard it would be to become a plumber, and if it paid well. I told him he would need training and a certificate, but plumbing is steady, good work, and suggested he talk to his carpentry teacher about this goal. He asked me about it several times throughout the class. I reminded him that although he should talk to his carpentry teacher, all of his classes will help prepare him for plumbing: there is extensive math, science, technical reading, and creative thinking involved in plumbing. Keep going, I told the student, it is not going to be easy, but do the best you can, and let your teachers work with you. Framing my role

One day I was in an earth science class with a particular teacher who always referred to me as “Dr. Rigolosi.” I do have a doctorate, and this is my title, but in schools I tend to not use “Dr.” title because I have found it creates a distance that I’m trying to avoid. On this particular day, a student I was working with perked up and asked, ”Oh wait, you’re a doctor? What kind?” I dread this kind of question from a student because I know what comes next.

“I have a doctorate degree.” “So, are you like a pediatrician?” “No, no, not at all. No medicine, my doctorate is in education.” I could see the excitement on his face fade fast. He preferred the idea that I was a pediatrician. “So you are not a pediatrician or a doctor, but a doctor of teachers?” Saying it this way sounds so over the top. “Well, yes, that’s one way of putting it,” I replied. “So if you are a doctor of teaching, what are you going to teach me?” “I was trying to read with you about the water cycle. Let’s go back to your reading. I’m trying to teach you right now.” He agreed, we returned to the water cycle, but his enthusiasm was evaporating. These are the conversations that keep me on my toes. And humble. The young people who are incarcerated at Rikers are in limbo. Many of them are awaiting a court date. A depressing reality is that Rikers is mainly made up of boys or men of color from low-income neighborhoods of New York City. Some of them arrive at Rikers and begin to attend school more consistently than they ever had. So what on earth can I, or any of the coaches who enter the schools at Rikers, do to help support the teachers who are charged with looking after them? Bearing witness

Remarkably, the retention of teachers at Rikers is extremely high. There are many teachers who have worked there for two decades, and some of those teachers even teach summer school, too. We bear witness for teachers during both positive and difficult classroom moments.

Sometimes you have to be a bit creative to notice the positive moments in classrooms at Rikers. For instance, on a different day in that same earth science class, the teacher was presenting on rocks: igneous, metamorphic, sedentary. We looked at pictures in textbooks and projected on the screen, and noticed the differences between them based on how they were formed. “You know, Mr., this would be so much easier if you could bring examples for us to look at. It’s hard to tell the differences between them on the screen.” The teacher looked at the student with a straight face and said, “Son, I can’t bring rocks into a prison.” “Oh, that’s true, Mr. — good point.” Everyone started laughing and it was a moment of levity. Of course, they joked, the teacher can’t bring rocks into prison! It was a moment of students being curious and engaged enough to ask their teacher for resources, forgetting for just an instance about their reality. In a meeting with the teacher later that day, I reminded him of this class moment — it was a quick moment, and I was happy to have been there to relive it with him. This happens so often in my classroom visits — I am there to review with teachers the small but wonderful moments that happen in their classes. So many micro events happen throughout a day; reviewing some of the moments they may not have reflected on can be empowering for a teacher, helping them to feel seen. Listening or bearing witness to the more challenging moments is just as important. I’ve met with teachers who are overwhelmed by the circumstances — by the students who are there one day but not the next because of court dates or circumstances from their housing, because of the constant underlying tension between the students and the correction officer in the room, or the teacher’s awareness that the wrong look or words could escalate into a fight between students. Listening, witnessing, and staying present for teachers when we meet or when I am visiting their classrooms is a way to experience, even for a moment, the difficulties that the teachers and students endure daily at Rikers. Malcolm Knowles, a psychologist who specialized in adult learning theory, explains how the role of a teacher working with adults can be different from a teacher working with children. In adult learning, Knowles explains that an adult teacher is “more a guide than a wizard.” In Elena Aguiliar’s The Art of Coaching Teachers she takes this idea of adult teacher as guide and extends it even more: “a coach needs to be an expert at listening: It is this skill which we must excel at more than any other.” When working with teachers who are in particularly high-stress schools or working with high-needs students, making space to listen, ask questions, and helping them frame their teaching experiences is a way to coach them. Making space for the teacher to say what they are seeing in their classrooms, and what they are feeling about the often tumultuous environment is a way to bear witness as a coach. Providing tailored support

Every school has a school culture that we are either told about as soon as we enter the school, or we figure out shortly after. At some schools, for instance, we quickly realize the copy machine policy, or that the culture around birthday celebrations is a big deal (or not).

One of the constant challenges at East River Academy is that the student body changes somewhat quickly. Between court dates and issues with student-to-student fighting, the student population can change from day to day; however, some students are there throughout the semester. Knowing this about the particular student body at ERA, we try to tailor our resources so that units can be shortened or extended as needed. Short stories are more popular than novels for this reason, and essays based on a short text are a more realistic assessment than an essay based on a novel. Having introductory lessons for new arrivals is crucial, so helping teachers accumulate resources for this transient student body has to become a part of our professional support. This requires research and conversations with teachers to get an understanding of their needs, challenges, and strategies they have already tried. We also work on adapting curricula they are already using to make it work for their students. This is specialized professional development in and of itself, as we have helped restructure units and lessons to fit the school’s needs. We cannot go into this school (or any school) pushing a particular curricula or series of best practices. Instead, working with the teachers’ needs in front of us and providing resources for their unique population is key to truly supporting their work. Reflecting & moving forward

In one of our last professional learning sessions with ERA teachers, I was charged with providing resources on ways they can incorporate more small group work in classes. This is a particularly challenging topic for teachers whose students can have difficult — sometimes violent —relationships, and may prefer to work alone.

In retrospect, what I wish I pointed out at the time was that their students are actually doing small group work frequently, but in an organic way. Just that day, I had witnessed a pair of students pulling out characteristics in a story, and unprompted, these two students started pointing out examples in the text to each other and writing these examples down. When students were practicing for the GRE math questions, I noticed a pair of students start talking to each other about the problems. This paired group work was happening, but on their terms. My question should have been — what is the best way to handle these positive paired work moments? Should we highlight them in class, or will that ruin the moment, and make it feel too much like “school?” Should we nudge for paired work even if some students like to work in pairs and others don’t? Is it best to just leave the pairs working if they are working well, and perhaps after class, praise the students for working so diligently? Or does that kill the vibe? This is a very nuanced conversation, and one I wish I had with the teachers instead of reviewing the typical reasons and methods for implementing small group work.

The moments I am sharing here don’t really feel like mine to tell. I am not one of the teachers who works 180 days of the year on Rikers Island; there is a part of me that hesitates even sharing glimpses inside the prison. But I also believe these stories have value, and there is a portion of our population who spend a chunk of their youth in prison, and adults who have dedicated their professional lives to helping them.

We need to hear more of their stories, and I am offering a small window into their world. Many schools can be challenging and humbling; they can keep us all on our toes. Working at a particularly high-needs school requires high-level and sensitive coaching. Bearing witness by listening, observing, and holding a mirror for teachers to talk through their classroom experiences is a way to enter the coaching work. Tailoring the professional development and resources is fundamental; it has to work for the particular student body. Finally, being a reflective practitioner and acknowledging how I can improve my craft is challenging and can feel self-deprecating, but it is also an essential step to providing quality professional support. When a school is riddled with challenges, it can be difficult to know how to support teachers and how to help them grow as practitioners. These three methods offer a starting point, positioning the coach as an active listener and observer, and encouraging the coach to be honest about the effectiveness of their professional support, willing to modify and adapt the support to answer the school’s needs.

Embarking on a journey through project-based mindsets and influences, alongside educators in China.

Our mission seemed somewhat straightforward: a weeklong workshop series for teacher educators in Shanghai focusing on PBL, or project-based learning. Considering the many workshops we have facilitated over the past two decades, ranging from topics such as creating rubrics to analyzing data, running a weeklong workshop in Shanghai on the topic of project-based learning is as fun as it gets!

We have partnered with YouCH, a professional development group in the MinHang section of Shanghai for several years, and have already facilitated workshops for YouCH educators on topics such as teacher research, 21st century learning, and fostering teacher leaders. YouCH, which is a play on words for supporting “youth” throughout the “ouch” of adolescence, is based in China, and our CPET team — Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang, Courtney Brown, G. Faith Little, Dr. Lance Ozier, and me — were all returning to Shanghai and looking forward to working with our YouCH colleagues again. Our plan for the week was solid: participants would work on a meaningful, real-life, weeklong project that would end with a culminating celebration. Mornings would be devoted to working on different aspects of our projects so that teachers could experience project-based learning on their own; in the afternoons, we would zoom out to unpack these experiences by debriefing the scaffolds within our lesson designs and teaching strategies; and finally, participants would have independent planning time. Excited for our workshop and visit to Shanghai, we packed our bags and we were ready to go! Cut to real life, post-pandemic. China had recently relaxed all of its COVID restrictions, resulting in a surge of colds and respiratory illnesses. A day after we arrived, we learned that schools were closing for most of the week due to the fear of spreading illness, and it was too late to reschedule our workshops. The best laid plans… A cultural exchange for educators

Instead of facilitating workshops, we found ourselves engaging in discussions and smaller sessions with our YouCH colleagues, participating in more formal meetings with the principal for Minghin High School, on a visit to the Huang Gongwang High School in HangZhou, and in meetings with professors and education officials in the Shanghai district.

Everywhere we went, we were welcomed warmly with tea and coffee, fruit and treats, and with a genuine love and interest in incorporating PBL into more schools throughout China. At the Teacher Education Centre under the auspices of UNESCO, the director inquired about the possibility of facilitating our PBL workshops in the western, more rural region of China, as a part of the “Rural Revitalization” program for teacher professional learning. They shared with us the belief that social and emotional wellbeing are important aspects of teacher education, as well as creativity — both of which are also key ingredients for project-based learning. At the Institute of General Education Shanghai Academy of Educational Sciences, we were greeted with Starbucks lattes and highlights from the professors’ research and papers on the importance of PBL. The director explained that PBL should not just be a “snack, but the main meal.” They believe curricula should ask real world questions, and students should be able to express themselves creatively as they research and present the possible answers. Again, we were amazed by the enthusiasm for PBL as a method to be included in all schools. Witnessing PBL in Shanghai

We also had the opportunity to meet teachers at a YouCH conference on PBL, and these teachers were already doing project-based learning units. At this full-day conference, we listened as elementary students showcased their PBL artifacts. We were most struck by Steven, a high school student, who shared his project — “Let’s Break the ‘Wall’ Together” — on period shame, which shines a light on the notion that menstruation is normal, yet girls are made to feel ashamed or embarrassed when they menstruate. This project evolved into a fundraising and social awareness project to combat period shame through education, and to raise funds to provide access to sanitary pads in more rural areas of China.

Not only were these students doing PBL, but the topics were open-minded and refreshing! Talking more to the teachers and students throughout the day, we realized that these student presentations were from a class that was dedicated solely to project-based learning In other words, these projects were not woven into their core curricular classes, but completed through an additional class. This is not to diminish the impressiveness of the projects (we were fawning over them!), but to highlight that including project-based learning into the core curriculum is a different endeavor. John Dewey's influence

Over a brunch of steaming dumplings, fish stew, and noodles on one of our final days in Shanghai, we asked Principal Jian from the MinHang section of Shanghai why he was so inspired and committed to PBL. Where did this inspiration come from?

He responded in Chinese, but we heard a name we recognized well in his explanation: John Dewey. The principal reminded us that Dewey spent time in China — two years and two months, the longest amount of time he spent anywhere abroad. Our Chinese colleague proudly recalled how Dewey not only shared his educational philosophy when he was in China from 1919-1921, but how he learned from Chinese culture, and was influenced by Chinese philosophies and practices. What does this mean for our work? Knowing this now, that at the center of the PBL work is a proud connection to Dewey, how might this influence our workshops, if we are given the opportunity to return? John Dewey believed that we must “give the pupils something to do, not something to learn; and the doing is of such a nature as to demand thinking; learning naturally results.” (1916, Democracy and Education). We can’t argue against learning by doing, but what does Dewey’s concept really look like in schools, on a day-to-day basis? Lessons from Maxine Greene

One of our CPET colleagues, Dr. Lance Ozier, reminded us all that our late and brilliant professor at Teachers College, Maxine Greene, was a student of Dewey’s. We were the last generation of students to have had Maxine as a professor, and we briefly swapped stories about her. My closest interaction to her was when my Narrative Research class with Professor Janet Miller visited her at her apartment, since she was 88 years old and no longer traveling to Teachers College. I happened to have my baby, Javier, who was just a few months old at the time, with me at her apartment.

Our class of doctoral students had prepared so many questions for Maxine; we were starting our doctoral research and wrestled with issues over perspective, what it means to be a fair researcher, and hungry for any writing suggestions to avoid being total bores. Maxine listened to our questions and nodded, but really could not stop looking at my baby. “He’s so curious,” she kept saying, “He just can’t get enough of the world!” Here we all were, excitedly trying to absorb as much of Maxine as we could, and here was Maxine, mesmerized by a baby. She was in awe of my baby’s curiosity, a spirit akin to her own. This is the kind of curiosity at the heart of research, teaching, and learning. And at the heart of project-based learning. What I remember most about our afternoon with Maxine is not her answers to our questions (we had so many!), but her authentic curiosity and interest in what was happening in front of her, and on that particular day, that happened to be watching my baby interact with the world by touching and poking at everything in his range. When we return to Shanghai, it is this curiosity that we will have to bring back with us, this curiosity that is at the heart of PBL, and at the heart of Dewey and Maxine Greene’s work. How do we infuse this deep curiosity and learning into our curricula, and our daily lessons? This will be our charge on our return. The realities of PBL

Although we did not have our weeklong workshop series, we did spend one afternoon with 75 teachers from the MinHang School, and gave them a taste of our PBL plans. One of the takeaways from that group of teachers was the importance of teaching students to ask questions, and then using student-generated questions to drive a curriculum. But we also can’t ignore some of the concerns we heard from the teachers, specifically: “PBL sounds like a lot of work, and who is going to support us?” We appreciated the real and honest question, and agree this needs to be ironed out. A new way of curriculum planning requires professional learning and ongoing support from colleagues.

We arrived in Shanghai with a plan to invite teachers to experience and then deconstruct project-based learning. It was a solid plan, but if we return, we may also invite teachers to reflect on the roots of PBL in China, namely, how do you plan with John Dewey’s philosophy in mind? We will keep our workshop practical, but also return to Dewey’s research: What does the constructivist teaching model look like in real life? How can we allow for more discovery for students? The interest in PBL is palatable, as we discovered in formal meetings and informal conversations with our YouCH colleagues. Our colleagues at the Shanghai Academy of Educational Sciences said it best: how do we make project-based learning the meal and not the snack? This is our collective charge.

Amplify small group instruction and strategic student grouping with this interactive approach.

Three years ago, we were quickly shifting our classrooms to online platforms as instruction was going remote for an indefinite amount of time. We tried to keep teaching throughout the pandemic and survived the snafus that happened throughout the day. (Remember that time you thought you were muted, but you weren’t? Bleh!) Our learning curves for online teaching grew exponentially, and many of us have incorporated the most promising practices into our classrooms today, such as using Google Docs for group projects or editing and commenting on a student paper in live time.

Although there is an educational app for just about everything, we suggest resisting the urge to default back to solely online learning (even while in person), and instead consider the unique benefits of being together in time and space. Let’s design opportunities for students to collaborate, and embrace the physical classroom by creating learning opportunities that take students away from the Chromebooks and into a live setting. Characterized by movement, interaction, and small group learning, station teaching is one of the six established co-teaching models that takes advantage of being together within the four walls of a classroom. As with all models, station teaching comes with its own unique benefits, challenges, and logistics — let's walk through this method in an effort to support you and your co-teacher in planning and facilitating this meaningful approach to learning.

What is station teaching?

Station teaching is when content and instruction are divided into distinct components or strands. Students are divided into equally sized, typically heterogeneous groups. Each teacher teaches a specific part of the lesson/content to different groups of students as they rotate between teachers. Students also rotate through center(s) where they complete an independent task.

What promises does this model offer?

Station teaching provides an opportunity for smaller group instruction and strategic student grouping. One of the more obvious benefits of station teaching is that teachers have an opportunity to work with a small group of students, thus allowing for more responsiveness to individual questions, preferences, and needs. Stations also allow us to leverage the benefits of strategic student grouping, where teachers are intentional in the way that students are grouped together in service of the learning goal. Typically, heterogeneous groups, in which students with a variety of learning traits and needs work together, work best for the station teaching model; at the independent stations in particular, students have the opportunity to learn from and teach each other. Station teaching allows for exploration of a topic or skill through multiple perspectives, entry points, and modes of expression. In Universal Design for Learning (UDL), a framework designed to ensure that all learners can access and participate in meaningful, challenging learning opportunities, one of the guiding principles is that learners differ in the ways that they perceive and comprehend information that is presented to them. Therefore, it is essential that teachers provide students with multiple means of representation of content. Stations easily allow us to provide representation of a topic in multiple ways; each station could focus on a different text, visual, or audio source. Similarly, each station can allow students to express their learning through a different medium or modality; another important principle of UDL. Station teaching allows the opportunity for natural “brain breaks” and movement. Research has shown that regular, short breaks in the classroom can help students increase their focus and reduce stress. With shorter “chunks” of academic engagement and clear, natural transitions between tasks, the station teaching model inherently incorporates breaks for students. The time it takes for students to travel to the next station could be leveraged to provide students with the physical or social engagement they might need to sustain focus: perhaps you play a song that students enjoy, or invite them to do a particular stretch. Station teaching can help strengthen a co-teaching relationship by providing the opportunity for shared ownership of planning and facilitation. Anyone who has co-taught before knows that it can be difficult to find a groove in which both teachers are easily and equally sharing the workload of lesson planning and facilitation; obstacles like lack of common planning time, unclear goals, and difference in teaching styles and preferences can often get in the way. If you and your co-teacher are finding yourself in a stage of your team development in which roles feel lopsided or undefined, a stations lesson can be a helpful way to help redistribute some responsibility. The ways in which content and instruction are divided in station teaching offer a clear path for delegating planning and teaching duties; each teacher can be responsible for the designing and facilitation of one station (with coordination and communication, of course!).

What are some potential pitfalls?

Noise level and space limitations can create challenges. With several groups of students working on different tasks simultaneously, some students (and teachers!) might find the level of noise and movement in the room to be an adjustment. Preparing students for this might be helpful; you might say something like, “Today’s class may be a bit louder than our typical class, but there will also be quiet moments at the end of the stations so you can collect your thoughts via writing.” It’s also helpful to think strategically about where each station is set up in the room; having the two teacher stations as far away from each other as possible is often the way to go, since teachers often have the loudest voices in the room! Careful attention must be paid to pacing. In contrast to learning centers, where students are moving between learning engagements at their own pace, station teaching is often characterized by coordinated rotation, where everyone moves on to the next station at the same time. This means that all stations need to take roughly the same amount of time, which can be challenging to anticipate in planning. All stations should have flexible tasks that can be shortened or extended with enrichment options or additional discussion questions, depending on how quickly a particular group engages in them. Not all content is well-suited for stations. One of the trickier dynamics of station teaching is that not all students will begin their learning in the same place; some will begin at the independent station, while others will begin at the station led by co-teacher A, while still others will begin at the station by co-teacher B. Because of this, it’s important that the topics or tasks at each station are non sequential — that one station is not a necessary prerequisite to engage with another. Therefore, stations are not ideal for topics or skills that require a specific or strict sequencing of tasks or texts. It’s also not ideal for tasks that require deeper and more sustained investigation or attention, since time spent at each station is relatively brief compared to a full class period. Rather, stations work great for topics that are broad with multiple strands, perspectives, or approaches, or for introductory explorations or final reviews.

How can independent work be structured?

Recent research has highlighted the benefits of letting kids do things on their own, and station teaching offers the opportunity for practicing independence. We have generally found independent stations should be built on familiar territory: a concept, graphic organizer, or task directions that students have seen before. Be sure to have all of the supplies ready at the independent station, and try not to overcomplicate the directions (this sounds obvious but can be challenging)! Here are just a few ideas for independent work:

What can this model look like in action?

Given the promises and potential pitfalls of this co-teaching model, we can determine the kinds of lessons and learning objectives that will be best suited for this instructional approach. Here are a few examples: 3rd grade ELA Students engage in stations that support them with the skills of determining the main idea of a text. At one teacher-led station, students are creating titles for chunks of text. At the second teacher-led station, students are reading a short text and asking: what is this story mostly about? At the two independent stations, students are sorting pictures into categories, or listening to an audio book and answering multiple choice questions. 7th grade Math To begin a new unit, students are engaging in an opening inquiry around the question: Why are surface area and volume important concepts in everyday life? At one teacher-led station, students make observations about water displacement when an object is dropped in a glass of water, and make predictions on whether the tray will be able to catch the displaced water; at another, students are tasked with wrapping a present; at another, they must choose the best tupperware container for leftover “food.” After visiting all the stations, students reflect on the guiding question and discuss with their peers. 11th grade US History Historians often teach an era through a variety of lenses, such as the culture, the key events and figures, and the different perspectives of an era; this approach lends itself easily to a station lesson. When studying the Progressive Era, for example, students can investigate: How did the growth in industrialization and urbanization lead to positive and negative changes in American society? At one teacher-led station, students can look at images from the time period (from photojournalists such as Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine) and notice the subjects and stories these photographers may be trying to tell about urban life in the early twentieth century. At an independent station, students can define key terms, such as “muckraker,” “progressivism,” “industrialization,” “modernization,” and The Gospel of Wealth. Students can look up these terms and record what they learn in the form of Cornell Notes or a Frayer Model. At another teacher-led station, the teacher can facilitate a reading of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle or The Story of Ida B. Wells, and ask students to make meaning of the text, and take notes on what the text conveys to the reader. After visiting all three stations, students can compare their notes and discuss the positive and negative impact of industrialization and urbanization during the U.S.’s Progressive Era.

The devil is in the details

The more you and your co-teacher can plan in advance for the logistics of station teaching, the more successful your lesson will likely be. How long will students spend at each station? How long will they be given to transition between stations? Which teacher will be responsible for keeping time and cuing the students? How will students know where to go next? (We suggest a slide or poster indicating the direction of rotation for that one!) Preparing all the materials in advance and having a clear and brief set of directions at each station is crucial (particularly at the independent station).

Practice pays off

While this article details the logistics of station teaching with an eye on co-teaching, we cannot overemphasize the importance of designing opportunities for students to interact with each other and with the physical space of the classroom in all classrooms. We know that students missed years of face-to-face interactions due to the pandemic; we suggest being proactive and creating moments for students to embrace a shared space and interact with each other in a low-stakes way. With all these dynamics and logistics, your stations lesson might not go perfectly the first time; don’t give up! We encourage you to reflect on the challenges, tweak it, and try it again. Stations might be a bit of a learning curve for your students as well, but as with any classroom protocol or routine, station rotation and engagement are skills that can be explicitly taught, scaffolded, and practiced. It’s our opinion that the work pays off, as we’ve found this approach to be an interactive and engaging way to punctuate particularly compelling topics in a curriculum.

Six practical co-teaching strategies that remain effective even in the absence of co-planning.

If you are a special education teacher and you are co-teaching in multiple subject areas, you may be running from classroom to classroom, with a cart or a crate of supplies, adjusting to your co-teacher’s teaching style and your students’ changing attitudes towards particular classes. Day after day, this can be exhausting and challenging! It is not uncommon for special education teachers to feel overwhelmed trying to stay on top of all of their classes, at all times. Throw into this mix co-teaching a new content class or one that is particularly unfamiliar to you, and it can feel impossible to stay afloat or to co-teach with confidence.

According to the NYCDOE, the purpose of co-teaching, or the Integrated Co-Teaching (ICT) program, is for the general education teacher and the special education teacher to “work together to adapt materials and modify instruction to make sure the entire class can participate.” For this to happen effectively, co-teachers need time to meet, think, plan, and reflect on their instruction together. But what can you do when that co-planning time isn’t possible?

Persevering in the absence of co-planning

This year, I am working in high schools where co-teachers do not have common prep periods to plan or debrief, or the special education teacher is co-teaching in five different content classes, so juggling between different classes and co-teachers is a real issue. Yet I have found that a special education co-teacher who was not able to participate in the planning of an ICT class can still be an effective and essential teacher in the room. There are ways that a co-teacher can continue to support students in a circumstance where co-planning is not an option.

Let me be clear: I am not advocating for this type of co-teaching model where one teacher is not prepared for class (due to lack of common planning time or other reasons outside of their control). Ideally, co-teachers are receiving professional support and have time built into their schedules to meet and plan together, and even discuss which of the six co-teaching models makes the most sense for each particular lesson.

If they do not have regular time to meet together, the content teacher can still prioritize delivering materials and lessons with adequate time for the special education co-teacher to make modifications, or create groups based on students’ needs. But even when these options aren’t possible, there are ways that a co-teacher can play an essential role in the classroom in the absence of adequate planning or prep time. By remaining active in class — as a learner, notetaker, or observer — the special education co-teacher can raise the level of instruction and thus ensure all students are benefiting from having two educators in the classroom.

A four-step process for jumpstarting your analysis.

Picture this: you just learned that you have access to your students’ test scores, or the standardized tests they took last year, and you are tasked with “analyzing the data.” You know your goal is to use those scores to inform your instruction, but what do you do? And where do you start?

Don’t panic.

Starting your analysis

As a doctoral student, I always appreciated understanding analysis in this way: “all analysis is basically sorting and lifting” (Ely, Vinz, Downing, and Anzul, p. 162). This visual of sorting and lifting helped me to take action, and not feel stuck or paralyzed by mounds of data that just sits there and does not analyze itself. Enter The 'Tions, a reflection tool that offers a pathway for making meaning out of a data set. With this resource, users can begin to navigate complex information they are charged with analyzing, by exploring four categories:

Using The 'Tions

While there is no single, prescribed way to use this tool, one recommendation is to begin in the top left quadrant — Confirmation — as a way to acknowledge one’s perceptions prior to diving into the data. This not only allows existing assumptions or hypotheses to surface before entering the data, but also nudges the user to begin thinking about the work and tap into prior knowledge. The Inspiration quadrant is a natural next step, as it encourages a fresh way to look at the data. If your data set is not particularly “inspiring,” consider identifying areas in the data that highlight strengths. As you make your way to the Revelation quadrant, don’t be surprised if this reveals similar information that you entered in the Confirmation section. This section will be most meaningful if you can remain open to taking a new perspective on the data at hand. Finally, use the Application quadrant to take into consideration your next steps after looking at the data. Consider how you will use your Inspirations and Revelations to inform practical next steps in your work. What’s a small step that you can take that would make the biggest difference?

Using The ‘Tions as a tool for reviewing data is a start, and can support the user as they begin to lift and sort the information before them. While The ‘Tions will not solve all of your data analysis issues, it will help you get unstuck and begin the important work of looking at data through specific lenses.

How one high school is constructing their own definition of rigor, in service of developing high expectations and meaningful work for students.

After several years of prolonged uncertainty and hardship, a feeling of normalcy seems to finally be settling in, and schools want to refocus their vision for high expectations and meaningful work for students. As coaches, we’ve noticed that “rigor” has become a topic of particular interest for school leaders this year.

However, not everyone has the most positive associations with the word, and we can’t really blame them (just look at the dictionary definition — yikes!). What we mean by rigor in the educational context is often unclear, and it’s for this reason that we believe in the importance of co-constructing definitions and characteristics of the concept as a school community. We’ve undertaken this endeavor with the Business Technology Early College High School (BTECH) — one of our wonderful partner schools in Queens, New York — and have been investigating the concept of rigor through a variety of entry points. Our inquiry around rigor began with a tool developed by our colleague, Dr. Roberta Lenger Kang, who envisions rigor as an odometer, a visual retake on Bloom’s Taxonomy. After working with the “Rigormeter”, the staff at BTECH engaged in inquiry around how to assess and establish criteria for rigorous questions. Here is a snapshot of how we explored this question and a look into the insights that were gleaned.

Assessing for rigor

What makes a rigorous question? The central way that teachers pursued this line of inquiry in our workshop was through a hands-on, minds-on activity. In small heterogeneous groups (mixed in terms of both content areas and experience), teachers were given an envelope of paper strips, each printed with a question inspired by real high school curriculum (How does the greenhouse effect work? What is exponential growth and where do we see it in our everyday lives?). Working collaboratively, teachers were tasked with sorting the questions into categories according to their perceived level of rigor. As we circulated the room, we heard teachers engaged in rich and lively discussion as they made decisions about how to rank questions according to their rigor level, and why.

Establishing criteria for rigor

After teachers spent some time engaging in the question sorting activity, we asked the small groups to reflect and discuss together: What criteria did you use to distinguish more rigorous from less rigorous questions? Then, when we came back together as a whole staff, we asked teachers: so, what does make a rigorous question? Here are some of the defining characteristic they articulated:

A rigorous question...

Additional definitions

After teachers generated their own ideas, we as facilitators offered a few additional criteria that worked to amplify and elaborate on the group’s working definition. The criteria we offered were inspired by some of the dispositions of competent readers delineated by Dr. Sheridan Blau in his article Performative Literacy: The Habits of Mind of Highly Literate Readers (2003) — with the thinking that if these dispositions allow for readers to make meaning of texts and “enable knowledge” (p. 19), then questions that inspire the cultivation of such dispositions will in turn cultivate meaning-making in general.

We proposed that a rigorous question also:

The importance of complexity and flexibility are also explored in Robyn Jackson’s How to Plan Rigorous Instruction (2010).

Next steps

After generating their own collective definition of a rigorous question and considering the Blau-inspired characteristics as well, teachers were given the opportunity to apply these new insights to an upcoming lesson. Teachers left the session with a new Do Now activity or slightly tweaked questions that asked for justification, for example. Most significantly, they left with clarity on what counts as a rigorous question. As we continue working with this school, we are designing next steps in the professional learning process. Our upcoming sessions can focus on when and how to use rigorous questions, specifically, at what point of the lesson, and how to assess student response. We can also explore activities or teaching moves that pair well with investigating rigorous questions. We might also reconsider our essential questions and check how they measure against our “rigorous questions” criteria. There are many possibilities for moving forward with our inquiry cycle. While there are plenty of resources and frameworks out there for teachers on creating compelling and meaningful questions, both facilitators and teachers found great value in doing some first-hand discovery, and in trying to articulate the nuance in what distinguishes rigorous questions from the rest.

Small moves that will help you hold on to that fresh teacher start a bit longer.

We have all seen memes of teachers beginning the school year versus teachers finishing the school year. The September teacher is energetic, cleancut and almost joyful; the June teacher looks disheveled and desperate. Think Michael from The Office on his best day compared with “Prison Mike.” It’s a funny meme, and relatable perhaps for our students, too.

But the truth is I never really feel that organized and ready for September. While I know I will never be that Pinterest teacher who has everything just so, if I spend a bit of time early in the school year planning, I can create the type of positive and organized learning environment that leads to a successful learning partnership.

Start with community building

This is a non-negotiable. I can imagine you are reading this and rolling your eyes. And frankly, I’m with you. There is nothing more irritating than community building when nobody is into it and the task feels superfluous. But hear me out: in order to have those discussions where students feel safe enough to explore and share their thinking, or feel comfortable enough to ask a question, we have to find a way to help students get to know one another. And we have to start somewhere, even if it's with just a few ice breakers that can be tweaked to fit your needs and the ages of your students. It may feel silly, but explain to your students that in order to do the hard work throughout the year, they need to know who is in the room with them, who their classmates are. Another way to think about this to help your students develop their emotional literacy within your classroom. Teaching students to talk to each other in honest and respectful ways is an ongoing and complex goal, but starting with some type of community building is the way to go.

Create or systematize the days of the week

As much as you can, of course. For instance, perhaps every Friday is a discussion day or a day to read and discuss current events, with the ask that your students connect it to your curricula. Perhaps every Tuesday and Friday are homework collections days, so students know what to expect and you can plan accordingly. You can make changes as the year progresses, but begin the year with a system to make your life and your students’ lives more predictable. My colleague Ashlynn Wittchow refers to this concept as making a plan for material management.

Plan broadly

Sketch out the year with the end of marking periods in mind so you have a strong sense of the perimeters of your curriculum. Look at weeks where there are no breaks and consider planning a field trip or asking a speaker to visit during those long stretches. The more you can sketch out your year and plan specific events in your classroom, the less anxious you’ll feel. I say this as a compulsive list maker, and Harvard Business Review will back me up on this. Again, your schedule or plans may change, but you can start plotting different elements of the year as a way to frame your backward planning.

The beginning of the school year can be overwhelming — new procedures and mandates, the mental and physical preparation of getting your room ready — and there are always new people to learn how to work with and get to know. But there is so much possibility at the beginning of the school year, which acts as a clean slate for teachers and students. Starting the year by building community, creating systems and structures, and determining a few key dates in the timeline are small moves that will help you hold on to that fresh teacher start a bit longer.

Subtle ways to help redirect your students.

I recently met with a colleague who had just returned from visiting a science teacher’s classroom, and when I asked her about her visit, she replied, “I love being in his classroom. I mean, he’s such a natural teacher.” I nodded, because I know just what she means. In this particular teacher’s classroom, the students produce thoughtful work and always seem engaged, even cheerful, which is no small feat for high schoolers. He has a gentle, relaxed way about him and when students start to act a little silly or get off task, he swiftly ushers them to their seat or nudges them to refocus.

I kept thinking about that phrase “he’s such a natural,” and what it means to be a “natural” at teaching. Or anything, really. I thought about the teachers I’ve worked with whom I consider to be “naturals,” and how they seem to teach effortlessly, how they bring humor into the classroom and make students feel safe and welcome so they can focus on learning and engaging with the content. Professor and mentor Ruth Vinz always pushes educators to name the verbs we use in teaching. In other words, what does it mean to “teach?” In this case, what are those moves this “natural” teacher makes to keep his class running smoothly, so class time is spent on learning?

Non-confrontational strategies

Our classroom management resource can help you encourage students in your class who may need some redirecting, and proactively stop flare-ups before they start. The goal is to maximize class time with your students, and this resource may provide fresh ideas. As you look at the list, notice which strategies you are already doing and which you can try. Below are some non-confrontational strategies from this resource that I use all the time. Please note: if anyone in class is in danger of hurting themselves or others, the teacher needs to reach out for help immediately.

Acknowledgement

To the class aloud, “I want to say thank you to x, y and z for working quietly on their assignment.” Or “Everyone is working so well, keep up the good work!” This strategy notices and names students who are on task, or working towards the right direction. Naming students who are doing the “right thing” is a great teacher trick, as it allows students to hear their name in a positive way. This acknowledgement can even sound like, “I love how you are partnering together and sharing your ideas,” as this feedback names the specific ways students are working in your class. When teachers use positive narration, they are creating a positive cycle that other students will want to engage in.

Proximity

Teacher stands close to students who are talking or disruptive. The teacher continues to stand there until the students have stopped their disruptions. This is such a classic teacher move that so many of us practice without even knowing it! When a student begins to get a bit distracted, walking over to the student and standing near their seat is often enough of a gesture to refocus the distracted student, instead of elevating the situation by saying their name in a disciplinary way. Along this same trajectory, it often helps to walk farther away from students who are speaking too softly for classmates to hear. Students tend to speak loud enough for their teacher to hear, but if the teacher is moving to the far side of the classroom, they will have to raise their voice to become more understandable. This is another non-confrontational way of nudging students to project their voices instead of asking students to “speak louder.”

Waiting

Teacher is speaking to the class when talking begins. The teacher freezes mid-sentence — doesn’t speak or move — and doesn’t speak again until the room is quiet. We can all remember that teacher who could silence a class with just a look. Perhaps by widening their eyes, or a slight tilt of their head. Before you knew it, students were shushing each other and sitting up a bit straighter. While there may be a touch of teacher magic happening in these scenarios, the “Wait” strategy is an effective way to redirect your class without raising your voice! Sometimes it takes a minute for students to get quiet. This strategy is a reminder that teachers don’t have to talk louder or speak over students; on the contrary, it is more powerful to pause and wait for class to quiet down. It’s also a good reminder that sometimes silence or “wait time” in the classroom is necessary — particularly during discussions or after the teacher or a student poses a question.

There are some teachers who may appear as “naturals” in the classroom, but if you start to notice and name their teaching moves, you will find that they are practicing non-confrontational strategies with their students. These small moves are ones that all of us can employ, and with some consistency and a bit of teacher swagger, perhaps we can all be “naturals” as well.

Three strategies for expanding student engagement in an in-person environment.

Lately I’ve been visiting classrooms and seeing students on their Chromebooks, typing away and answering text-based questions on a Nearpod or on Google Classroom. Teachers are circulating and peering over their students’ shoulders, checking their screens to get a sense of where students are in their classwork, and to ensure they are not sliding between windows to play games or watch videos. At the end of class, teachers sometimes ask students to share a few of their answers, remind them to submit their work, and then class is dismissed. As students are packing up, the teacher may remind students to finish what they didn’t complete for homework.

In a sense, it’s almost as though this type of classroom instruction could have been facilitated in a remote setting. Students are so accustomed to educational apps that they can do their classwork without even attending class. But we are no longer remote, and as far as I can tell today, most schools are not planning to return to a fully remote school program. So how can we make the most of being together in person and increase in-class interactions?

Get students talking

The simplest way to get your students engaged is to include “turn and talks” in your lesson plan, allowing conversations to happen in pairs. Decide on the most strategic moments to include a turn and talk — this could be any time you want students to mull over or think through a key concept during class. Asking students to talk to the person next to them will help them practice their thinking in a low-stakes way. I often find that when just one or two students are participating after a teacher poses a question, it signals that other students are not yet ready to share their thoughts with the rest of the class. Posing a question and asking students to turn and discuss it with the person sitting near them is a way to get students thinking about the key topic, and provides a moment for the teacher to circulate and listen in on students’ thinking. This creates a perfect opportunity to cull new voices in the whole class participation: “What you said, Jess, is a really helpful explanation as to why it can inadvertently hurt our economy. Would you mind sharing this out to the whole group when we come back together?”

Make thinking visible

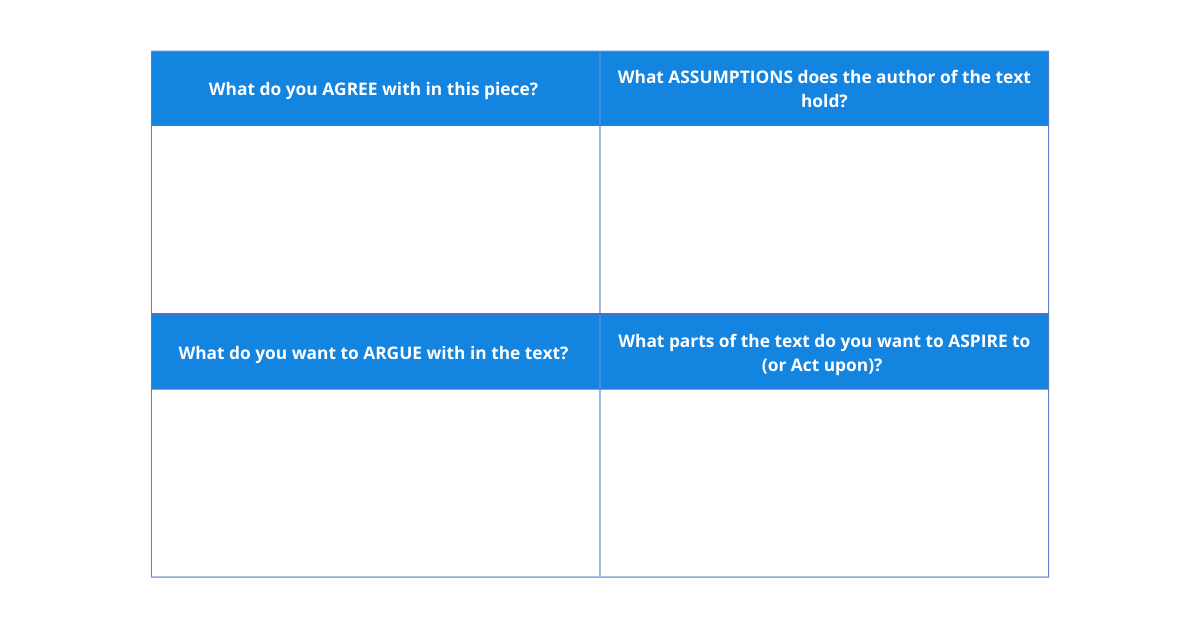

Pull out some chart paper and ask students to share their thinking in groups and on paper. Working on Google Docs as a group can be useful for co-writing or sharing ideas, but working on chart paper is a more strategic way to share thinking within a group and to help make the thinking visual. Some graphic organizers lend themselves well to chart paper, particularly when students are using a graphic organizer to process a concept. For example, the 4 As Protocol works well on chart paper. My colleague Courtney Brown and I have often used this protocol on chart paper as a way to demonstrate thinking about a text through these specific lenses, which can look like this:

Bring voices to the whole class

If you were a real rookie on Zoom during the pandemic (like me) and tried to have a full class discussion (like me), you quickly longed for the days to return to in-person instruction. I wince when I recall the first time I asked students to discuss what we had read — there were moments of everyone talking over each other, or everyone muted and awkward silence. While I had asked students to collect their thoughts in writing as the primary step to having a discussion, I could not ask students to turn and talk casually for 45 seconds. I could have created breakout rooms for a minute or two, but somehow breakout rooms seem too formal. Now that we are in class together, let’s take the opportunity to help our students learn how to have a discussion as a whole group. Work up to a larger discussion by building small steps along the way: first a quick write on the topic, then a turn and talk, and finally, opening up the chance for students to share with the whole class. Using a discussion rubric in live time and then reflecting on the discussion is another way to remind students what makes for an effective conversant.

During the pandemic, we were flexible and experimented with different online learning tools. We discovered ways to teach and assess students, and we did the best we could during a most difficult time. But now that we have returned in person, let’s take advantage of being together and find ways to use the lessons we’ve learned during remote learning to increase interactions in our in-person classrooms.

How do we decide which words to teach our students?

In Including All Learners, a course I co-teach with my colleague Jacqui Stolzer, we design our content based on the questions we wonder about as teachers. One that comes up often is: How do we decide which words to teach our students? Asking this question challenges us to think about how to focus our instructional time, and nudges us to be more purposeful in designing our curriculum.

Understanding tiered vocabulary

One of the ways we decide which words to teach is by using the tiered vocabulary concept developed by Dr. Isabel Beck. Beck thinks of vocabulary words as belonging to one of three categories:

While it is interesting to group words into these three categories, how does this practice impact our instructional decisions?

Narrowing your focus

When designing lessons and prioritizing instructional time, it may be helpful to consider which tiers and key terms are worthy of classroom instruction. As we can see above, Tier 3 words are easy to identify; these are the words that we need to teach in order for students to understand a particular concept. For example, in an ecosystem unit of a Living Environment course, words such as “abiotic” and “biotic” are Tier 3 words that are necessary terms in the unit; they are the specific words used to identify non-living or living parts of an ecosystem. In a sense, Tier 3 words are easy to determine in a curriculum because they are entwined with concepts in a particular unit. Tier 2 words, however, are often not taught explicitly since the assumption is that students already know what they mean. It’s the Tier 2 words that need extra attention in our classrooms. These are the words to spend time teaching and modeling for your students. What this looks like will vary depending on your grade level and content area.

Modeling for your students

Consider a Tier 2 word such as analyze. Most students are familiar with that word by the time they reach middle school, but what does it really look like in math or science or English? When students are asked to analyze a text, it’s helpful for teachers to model this work, demonstrating the pieces of a text analysis and sharing the tools students need to analyze a text on their own. Think about all the steps that are imperative for analyzing a text. If I were modeling how to analyze a passage, I might:

Analysis can change shape depending on the class — in science, analyzing lab data might look different from analyzing a passage in English. But in both cases, dedicating instructional time to demonstration of the term will help strengthen students’ skills, giving students access to academic thinking and language.

Tiered vocabulary can help you classify key terms for your grade level and content area, and as a result, make instructional decisions that hone in on teaching new or unfamiliar words for your students. Finding a balance between content-specific, Tier 3 words and more general academic terms like those in Tier 2 can help narrow your focus and increase student comfort with the words they encounter in your classroom.

Capitalize on critical thinking, reflection, and action to keep your students actively engaged.

“It’s so hard for me to come up with something to do every day in my class. I know my lessons should prepare students for their summative assessment, but, like, what do I do every day? Every class?”

This was how my meeting began with a relatively new teacher I am mentoring. He knows where he needs to end up in his unit, but what can he do in every single class that doesn’t feel monotonous? What various activities can he use in his class that work towards a concept he is building? In his case, his summative assessment will be an analysis of a theme in the class novel, but he also aims to use the text to teach other concepts, other literacy skills. Enter our student engagement resource (download here). It’s so easy to get stuck doing the same activities each day. Using this resource, you can unlock practical ideas for engaging students cognitively, and find ways to spur students to think about the class text or class concepts from multiple perspectives. I particularly appreciate how these activities are easily adaptable, and can be rooted in concepts students are learning. Across four categories, you can imagine fresh lesson ideas, no matter where you're at in your career.

GET STUDENTS...

Thinking Quote-ables: Pull meaningful quotes from student writing or discussions, and post them around the room. This activity is a way to synthesize students’ ideas, reflections, and wonderings around a topic, and the result is that student voice becomes a new collaborative text. When students see meaningful snippets of their own writing on chart papers around the classroom walls, they will feel seen. A wonderful add-on to this could be to ask students to respond to others’ writing using post-it notes or directly on the chart paper itself. This activity reinforces ideas discussed in class, celebrates student voice, and helps students see concepts through their classmates’ perspectives.

GET STUDENTS...

Doing Get centered: Create student choice by organizing 2-3 different activities around a text (vocab, drawing, summarizing). Allow students to choose which center they want to focus on. Creating a “centers” lesson is a way to get students up and out of their seats to focus on a topic of study using various manipulatives. A variation of this is to create “stations” where students rotate between the stations (or center). Station or center lessons require quite a bit of planning in order to create independent activities that are allotted a similar timeframe, but a “centers” lesson ensures students are actively engaged, and teachers are observing and providing support when needed.

GET STUDENTS...

Feeling Gratitudes: Say thank you to all students on task until everyone is participating. A positive way to get students on track instead of focusing on what they are not doing: “Thank you, Tiffany, Fatima, and Derek, for sitting down quickly and taking out your notes. Thank you, Marcus, for getting started right away on our opening question…” These small statements of praise help to build a classroom culture where students feel seen and appreciated. I would add to this practice by suggesting that ending your class with gratitudes is a way to synthesize all of the significant work that students contributed throughout the class. This could begin a cycle of positivity in a classroom, where students are praised throughout class for staying on task, and at the end of class for their insights and participation.

GET STUDENTS...

Believing Better or Worse?: Ask students to choose which of two options is the best response to a problem. Explain why in writing or discussion. This question creates a binary that provokes us to take a stand that is backed in evidence and reasoning. To answer this question, students must consider the complexity of an issue and come to a decision that presents the best solution. Most of the strategies in this category include two acts of literacy: writing and discussion. If there is one takeaway from this category — or from all categories listed above — it is this: give students time to process and capture their thoughts in writing as a way to engage them. Quickwrites, or brief moments to jot down ideas and gather thoughts in writing before sharing verbally, are a key ingredient to processing and thinking through a concept.

It can be difficult to remember all that we have learned about teaching through the years. Whether you are a new teacher or have years of teaching experience, it's still possible to find fresh ideas for keeping your students engaged and actively thinking in your classroom!

Keep students engaged with an intentional, research-based approach.

In college, I played rugby on an intramural team. As a “back”, my role was to run the ball up the field and score a “try” (basically, a touchdown) or pass the ball to a teammate so they could score. The players on the opposing team would try to tackle anyone with the ball, so the goal was to either pass to a teammate or outrun and evade defenders in order to score. It can be intimidating (who am I kidding, terrifying!) to run down the field with a scrum of women running towards me with the intention of taking me down. One lesson I learned quickly was not to panic and get rid of the ball like a hot potato before I got tackled — our captain would call this a “hospital pass”, as in let me throw away this ball before I get tackled by passing it to someone who is already so heavily marked that they may end up in a hospital. If we did a “hospital pass” in practice, it meant extra push ups — it was a careless move. Ultimately, we knew it would be better to pass purposefully than to give away possession of the ball or risk a teammate getting hurt.

Those of us who work in schools have so many concerns as we return to school this year. Our concerns are warranted: we are concerned about students who may have missed many of their Zoom classes, and we are concerned how our students are processing this past year filled with personal loss, sickness, and political turmoil. The New York Times recently reported that “by the end of the school year, students were, on average, four to five months behind where students have typically been in the past, according to the report by McKinsey, which found similar impacts on the most vulnerable students” (Mervosh, 7/28/21). Many educators and parents are deeply concerned about students who may have experienced what many are calling learning loss. We are looking for solutions as we re-enter our schools. But we need to think strategically — we cannot panic and toss the ball away in fear. We need to be thoughtful in our intentions, not reactive.

Creating positive relationships

If ever there was a time to think of how to deeply engage students in our classwork, in our content, and in discussions about what makes each subject area so compelling, now is the time.

Linda Darling Hammond, president of the Learning Policy Institute and professor emeritus at Stanford University, addresses how to reenter schools after this tumultuous year of remote and hybrid schooling. She reminds us to recall the most effective research-based learning methods, which include: “positive relationships and attachments… the essential ingredient that catalyzes healthy development and learning...and enables resilience from trauma” (Hammond, Forbes, 4/5/21). But positive relationships do not develop organically in schools; teachers and administrators can purposefully create positive relationships between the adults and students and between students and students. Positive relationships in school help students stay engaged and interested in learning. According to research from the Carnegie Corporation, “the degree to which students are engaged and motivated at school depends to a great extent on the quality of the relationships they experience there (Eccles & Midgley, 1989, p. 140; Lee & Smith, 1993, pp. 164, 180). Supportive relationships are necessary, although not sufficient without high-quality curriculum and teaching, to foster high performance among young adolescents” (Jackson and Davis, Turning Points 2000, Teachers College Press: 2000, p. 123). This concept is something we know to be instinctively true: relationships matter in every part of life, particularly in schools with young people. And while “high-quality curriculum and teaching” are paramount to students’ success, positive relationships in schools are equally important.

Encouraging connections

There are ways to create positive relationships through the content we focus on in our curriculum, and in the ways we teach students to interact with one another. Hammond also reminds us, “Children actively construct knowledge by connecting what they know to what they are learning within their cultural contexts. Creating those connections is key to learning.” Again, helping students to build connections between new and prior knowledge is something teachers can plan for and create.

Putting Darling Hammond’s advice into action can be as simple as creating opportunities for interactions among students. For example, instructing students to talk to one another first in pairs for a set amount of time, and then encouraging pairs to expand to form small groups. As the groups continue to expand, students move toward whole class discussions. Setting students up with these types of discussion structures — moving from smaller groups to larger groups — and then encouraging them to debrief their discussions in writing or as a whole class is a way to build content knowledge and foster positive relationships. Constructing ways for students to discuss content-specific ideas and helping students process what they are learning and what questions they have is a way to keep students actively engaged in their classes.

As we get reacquainted with in-person instruction, I imagine there will be last minute programs and initiatives that will aim to catch students up and get them back on grade level. But let’s commit to no hospital passes. Let’s commit to what we already know about effective ways of learning and remain strategic about keeping students engaged. The ownice is on us to find ways for students to connect with the content. Let’s move through this year with teaching strategies that are intentional, rooted in research, and that will keep our kids engaged and talking.

In order to succeed, students need to practice connecting and empathizing with others.

As I sit here at my computer, I could also be video chatting with a relative in Argentina while checking airfare prices, ordering pizza to be delivered in an hour, checking the weather for next weekend, finding an inspirational quote to add to my workshop tomorrow, and checking who the seven dwarves are because it’s been bugging me. And the funny part is, none of this would seem unusual to you! With a smartphone or computer and a good wifi connection, knowledge and information is a click away. Watching my own children attend school from home this past year gave me insight into how much technology is affecting schoolwork. Yes, they are still doing math, still reading, still writing, but there is also this: “Alexa, how do you spell “suggestion?” “Alexa, which fraction is larger- ⅔ or ¾?” Yikes!

When we think about the future, we tend to imagine the remarkable technology that will continue to develop. And so, when thinking about what skills our students need to thrive in the 21st century, the gut response is more tech skills, more computer savviness. But acquiring more tech skills can only get us so far. What students need is the ability to think critically, and the ability to collaborate with diverse thinkers. To do this, our students need to be taught how to connect and empathize with others.

Teaching empathy

When I think about students who have really stood out to me, from middle school to graduate school, I think of the students who could work with anyone — the ones that helped their classmates shine bright. Those are the students I remember the most. I’d like to make a case that it is possible to teach this, or put structures in place to teach students to think outside of themselves. To teach students the importance of getting along with others, and seeing the world from another point of view. In a recent speech by President Joe Biden, he urges Americans to practice empathy for the health of our country. He reasoned: “For empathy is the fuel of democracy. Let me say that again: Empathy — empathy is the fuel of democracy, a willingness to see each other — not as enemies, neighbors. Even when we disagree, to understand what the other is going through.” That ability to see “what the other is going through” is something we can teach. And as President Biden points out, this quality that may have once been thought of as a soft skill is one that we need to fuel our democracy. One way to “understand what the other is going through” is through reading. While I am not an immigrant, I can dive into the lives of Jhumpa Lahiri’s characters in The Namesake and experience Ashima’s deep loneliness in Cambridge, longing for her family, feeling like a foreigner. I can also experience her delight when she realizes she can recreate her favorite street snack from Calcutta — a mixture of peanuts, Rice Krispies, onions, and spices. As a teacher reading The Namesake in an English or Humanities class, I would invite students to sit with Ashima for a while. Live in her loneliness a bit, stew in the feeling of everything feeling unfamiliar. Offer students a choice for how they can engage with the characters, such as:

There are so many ways to empathize with characters in English or Humanities classes, through reading, writing, and discussions.

Connecting to content areas

In an interview with Life Magazine, James Baldwin explains, “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.” Baldwin reminds us all what it means to be human, and through literature we can feel each other’s pain, knowing we, too, have experienced the same. While the particulars may be different, we all have hard moments of hardship that have “tormented” us in some way. But how do we explore this in subject areas other than English or Humanities? Or for students who may not be able to empathize in such a way? For content area classes, Facing History offers a tool to help students forge a connection with something they have read or are exploring.

Using this tool invites students to spend time thinking, probing, and considering how an event or problem is relatable in some way. Facing History suggests using these prompts with the chart above (available for download here):

Students can easily use this tool in History or Science, as they are learning about scientific discoveries or ethical dilemmas involved in scientific explorations. If we want to help our students become 21st century thinkers, we have to create scenarios in which they are stepping outside of themselves, extending into another’s world in some way. This is what will help students build ideas together. This is what will make our students think more complexly.

Our equations can always be situated in the real world, which offers our young people another perspective. Another way to teach empathy in all subject areas is to normalize students helping each other, teaching one another, and working together to solve problems. Teaching students how to teach their classmates signals to them that you value collaboration, and that the ability to teach and work together are significant, valued characteristics. Encouraging students to step into a teaching role will also help them gain a greater awareness of the topic at hand — when students take on the qualities of a teacher, they are not only learning how to work with their classmates, but simultaneously becoming more of an expert on the subject.

Technology will continue to develop at a rapid pace, and knowledge will continue to be accessible to all of us. Creating situations where students learn to step outside of themselves is what will propel our students into more complex and critical ways of thinking. We must continue to focus on how we can help our students think about each other and our world, and encourage them to collaborate and share ideas. As President Biden put it, this is what fuels our democracy. This is how we will stay 21st century ready.

Baseline assessments are powerful — when you ask the right questions.

James Popham, our favorite assessment guru, explains that “the right data will, in fact, help teachers do a better job with students. Those are the data we need.” It makes sense that if we are using data to inform our instruction, that data needs to reveal authentic learning.